Dark Star (film)

| Dark Star | |

|---|---|

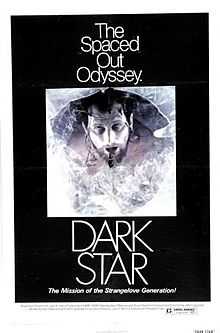

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Produced by | John Carpenter |

| Written by |

John Carpenter Dan O'Bannon |

| Starring |

Dan O'Bannon Brian Narelle Cal Kuniholm Dre Pahich |

| Music by | John Carpenter |

| Cinematography | Douglas Knapp |

| Editing by | Dan O'Bannon |

| Studio |

Jack H. Harris Enterprises University of Southern California |

| Distributed by |

Jack H. Harris Enterprises Inc. Bryanston Distributing (1975) (USA) VCI Entertainment (USA, VHS & DVD) Astral Films (1975, Canada) |

| Release dates |

|

| Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60,000 |

Dark Star is a 1974 American comedic science fiction motion picture directed, co-written, produced and scored by John Carpenter, and co-written by, edited by and starring Dan O'Bannon.[1]

Plot

In the middle of the 22nd century, mankind has reached a point in its technological advancement that enables colonization of the far reaches of the universe. Armed with artificially intelligent "Thermostellar Triggering Devices", the scout ship Dark Star and its crew have been in space alone for twenty years on a mission to destroy "unstable planets" which might threaten future colonization.

The ship's crew consists of Lt. Doolittle, Sgt. Pinback, Boiler, and Talby. Commander Powell, their superior officer, was killed by a faulty rear seat panel, but remains on board the ship in a state of cryogenic suspension. The crew perform their jobs in a state of abject boredom as the tedium of their task has driven them around the bend, with only each other, an increasing number of (sometimes comical) systems malfunctions (for example, an explosion in a storage bay has destroyed the ship's entire supply of toilet paper) and the soft-spoken ship's computer for company. They have attempted to create distractions for themselves - Doolittle, formerly an enthusiastic surfer, has constructed a musical bottle organ, Talby spends all his time in the ship's observation dome watching the universe go by, Boiler enjoys smoking cigars and target practice with the ship's laser rifle, while Pinback enjoys playing practical jokes on the other crew members, maintains a video diary, and has also adopted a ship's mascot in the form of a mischievous alien "beachball" that refuses to stay put in the food locker and forces Pinback to chase it all over the ship.

Pinback's video diary includes an earlier entry in which he states that he is actually liquid fuel specialist Bill Froug, who accidentally took Pinback's place on the mission after failing to rescue Pinback from committing suicide by wading into a fuel tank before the mission.

While navigating an asteroid storm, en route to their next target (the Veil Nebula[2]), the Dark Star is hit by a bolt of electromagnetic energy, resulting in an onboard malfunction and bomb #20 receiving the order to deploy. With some difficulty, the ship's computer convinces bomb #20 that the order was in error and persuades the bomb to disarm and return to the bomb bay. To the complete disinterest of his crewmates, Talby decides to investigate the fault, and discovering a damaged communications laser in the airlock, Talby dons a spacesuit to investigate further. While attempting to repair the laser, Talby is blinded and inadvertently triggers a more serious problem, causing extensive damage to the ship's main computer and damaging the bomb release mechanism on bomb #20.

On arrival at their target planet, the bomb is armed in the usual way, but then the crew discovers they cannot activate the release mechanism and attempt to abort the drop. Bomb #20 becomes belligerent and refuses to disarm. Its detonation countdown is in progress and it refuses to abort the countdown sequence. The other crew members attempt to talk the bomb out of blowing up. Doolittle revives Commander Powell, who advises them to teach the bomb the rudiments of phenomenalism, resulting in a memorable philosophical conversation between Doolittle and the bomb. Bomb #20 aborts its countdown and retreats to the bomb bay for contemplation, and disaster appears to have been averted. Pinback addresses the bomb over the intercom in an attempt to finally disarm it.

Doolittle has mistakenly taught the bomb Cartesian doubt, and as a result, later in the film, the bomb determines that it can only trust itself and not external inputs, states "Let there be light," and promptly detonates. Pinback and Boiler are killed instantly. Commander Powell is jettisoned into space encased in a large block of ice, and Talby is taken away by the Phoenix Asteroids (a cluster of glowing asteroids he had a fascination with) to circumnavigate the universe. Doolittle, who previously expressed his love of surfing and how much he misses it, finds an appropriately shaped piece of debris and "surfs" down into the atmosphere of the planet, burning into an incandescent speck.

Quotation

Pinback watches his videodiary:

| “ | "For official purposes this recording instrument automatically deletes all offensive language and/or gestures"

Pinback: I went to Doolittle on the hall today. I said "<deleted> Doolittle". He said "<deleted>". I said "well <deleted><gesture deleted> and he didn't get it". |

” |

Cast

- Lt. Doolittle - Brian Narelle

- Sgt. Pinback - Dan O'Bannon

- Boiler - Cal Kuniholm

- Talby - Dre Pahich

- Commander Powell - Joe Saunders

- Computer - Cookie Knapp

- Bomb #19 - Alan Sheretz

- Bomb #20 - Adam Beckenbaugh

- Mission Control - Miles Watkins

- Alien - Nick Castle

Production

Screenplay

Director John Carpenter and Dan O'Bannon wrote the screenplay. Six years later, the basic "Beachball with Claws" subplot of the film was reworked from comedy to horror,[1] and became the basis (along with an unpublished story about gremlins aboard a B-17) for the O'Bannon-scripted science fiction horror classic, Alien.[1][3]

Filming

Working on an estimated $60,000 budget, Carpenter and O'Bannon had to make production design from scratch. In the "elevator" sequence the bottom of the elevator is actually rolling on the floor. The device used to roll the elevator base was a Moviola camera dolly normally used on the small sound stage in the old USC Cinema building (a former horse stable). The steering arm of the dolly can be seen in the "elevator's" underside. Talby's starsuit backpack is made from Styrofoam packing material - probably from a TV set - and his spacesuit chestplate is made from a muffin tray. The double rows of large buttons on the bridge consoles are ice cube trays illuminated from beneath. Sergeant Pinback's video diary is an 8-track tape and the machine he uses to read it and record it is a microfiche reader. O'Bannon also starred in the film in the role of Sgt. Pinback.

Special effects

Much of the special effects seen in the movie were done by Dan O'Bannon, ship design by Ron Cobb, model work by O'Bannon and Greg Jein, and animation was by Bob Greenberg.[citation needed]

The bombs are made from an AMT 1/25 scale semi-trailer kit and parts of a 1/12th scale model car kit; "Matra", the name of the car brand, can be seen on some parts in some shots.[4] The space suits are made to resemble the space suit of the Mattel action figure "Major Matt Mason", which was used in slightly modified form as a miniature for effects shots. Cobb drew the original design for the "Dark Star" ship on a napkin while they were eating at the International House of Pancakes.

The film featured the first hyperspace sequence to show the effect of stars rushing past the Dark Star vessel in a tunnel-effect (due to superluminal velocity) which was used in Star Wars three years later.

Release

Although destined for eventual cinematic release in 1974, this was only possible as a consequence of a successful series of showings at a number of film festivals in 1973. Originally the film was a 68-minute student short filmed on 16mm film. The movie was seen by producer Jack H. Harris, who gained the theatrical distribution rights to the film, and arranged for it to be transferred to 35mm, and paid for the addition of 15 minutes which brought the movie up to feature film length.[citation needed]

For theatrical release, parts of the film were re-edited to make it feel more like a 3-part story and extra footage was filmed to bring it up to a more substantial running time. This included the bottle-organ scene, the alien chase, elevator scenes and more.

John Carpenter would later lament that as a result of this padding into a feature length movie, their "great looking student film" became a "terrible looking feature film".

Director's Cut

John Carpenter and Dan O'Bannon re-edited the film into a "director's cut", removing much of the footage shot for the theatrical release and adding new special effects.[citation needed]

Home media

The film was released on DVD March 23, 1999 in a single disc edition. Several years later a special two-disc "Hyperdrive Edition" DVD was released in 2010 by VCI Entertainment and contains both the Director's Cut and a longer Original Theatrical Release, as well as a long featurette explaining the origins of Dark Star and how it was produced. A fan commentary also provides a lot of trivial information about the film.

Reception

Dark Star can be considered a black comedy although it was marketed by Harris as more of a serious science fiction film. As a result, most of the cinema-going audience did not expect the humour and Dark Star's reception suffered from not reaching its intended audience. The home video cassette revolution of the early 1980s saw Dark Star become a cult film among sci-fi fans.

Critical response

Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a 79% fresh rating, with the following consensus: "A loopy 2001 satire, Dark Star may not be the most consistent sci-fi comedy, but its portrayal of human eccentricity is a welcome addition to the genre."[5] Roger Ebert gave the film three stars out of four, writing: "Dark Star is one of the damnedest science fiction movies I've ever seen, a berserk combination of space opera, intelligent bombs, and beach balls from other worlds."[6] Leonard Maltin awarded the film two and a half stars, describing it as "enjoyable for sci-fi fans and surfers"; he also compliments the effective use of the limited budget.[7]

Analysis

Carpenter has described Dark Star as "Waiting for Godot in space."[8]

Commentators have noted that the film's ending closely parallels the short story "Kaleidoscope" by Ray Bradbury, from his 1951 short story collection The Illustrated Man.[9]

Influence

The Indie rock band Pinback frequently uses sound effects from the movie throughout their discography, and adopted their name from the character, Sgt. Pinback.

Doug Naylor has said in interviews that Dark Star was the inspiration for Dave Hollins: Space Cadet, the radio sketches that evolved into the popular television science fiction situation comedy Red Dwarf.[10]

The character Pinback also inspired the character name Pinbacker, the antagonist in Danny Boyle's 2007 film Sunshine.[citation needed]

Dark Star has been cited as a large inspiration for Machinima series Red vs. Blue by the show's creator Burnie Burns.[11]

Soundtrack

The music for Dark Star is mostly of a pure electronic style and was made by John Carpenter using synthesizers.

The theme song played during the opening and closing credits is "Benson, Arizona". The music was written by John Carpenter, and the lyrics by Bill Taylor, concerning a person who travels the galaxy at light speed and misses their beloved back on Earth.[12] The lead vocal was John Yager, a college friend of Carpenter's. Yager was not a professional musician "apart from being in a band in college."[13]

Further reading

- Holdstock, Robert. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Octopus Books, 1978, pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-7064-0756-3

- Cinefex magazine, issue 2, Aug 1980. Article by Brad Munson: "Greg Jein, Miniature Giant". (Discusses Dark Star, among other subjects.)

- Fantastic Films magazine, Oct 1978, vol. 1 no. 4, pages 52–58, 68–69. James Delson interviews Greg Jein, about Dark Star and other projects Jein had worked on.

- Fantastic Films magazine, Sep 1979, issue 10, pages 7–17, 29–30. Dan O'Bannon discusses Dark Star and Alien, other subjects. (Article was later reprinted in "The very best of Fantastic Films", Special Edition #22 as well.)

- Fantastic Films magazine, Collector's Edition #17, Jul 1980, pages 16–24, 73, 76–77, 92. (Article: "John Carpenter Overexposed" by Blake Mitchell and James Ferguson. Discusses Dark Star, among other things.)

- Bradbury, Ray, Kaleidoscope Doubleday & Company 1951

- Foster, Alan Dean. Dark Star, Futura Publications, 1979. ISBN 0-7088-8048-7. (Adapted from a script by Dan O'Bannon and John Carpenter by the author of Alien (film))

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Maçek III, J.C. (2012-11-21). "Building the Perfect Star Beast: The Antecedents of 'Alien'". PopMatters.

- ↑ Carpenter, John; O'Bannon, Dan. ""Dark Star", short film script". Retrieved 2013-06-05.

- ↑ Creative Screenwriting magazine, Sep/Oct 2004, Vol. 11 No. 5, pages 70–73. (Article: "Alien, 25 years later: Dan O'Bannon looks back on his scariest creation" by David Konow. Discusses, among other things, how the "Beach Ball Alien" scenes in Dark Star were an inspiration for Alien.)

- ↑ "Dark Star Bomb 20 forum thread". The RPF. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Rotten Tomatoes - Dark Star". Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Dark Star (***)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ Maltin, Leonard (2009), p. 320. Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide. ISBN 1-101-10660-3. Signet Books. Accessed May 8, 2012

- ↑ "Dark Star movie review – Film – Time Out London". Time Out. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ↑ "Dark Star". "Bradbury’s story is about a group of rocket men floating away from each other in space after their ship has exploded. Eventually only two men are left in radio contact; one of them is carried off by an enchanting, kaleidoscopic meteor swarm, and the other falls to earth as a shooting star. This situation is exactly recreated at the end of “Dark Star,” and some of the dialogue is adapted directly from Bradbury’s text."

- ↑ Interview: RED DWARF Writer / Co-Creator DOUG NAYLOR". Starburst, October 1, 2012, Retrieved October 6, 2012

- ↑ Gus Sorola (3/21/12). "Rooster Teeth Podcast". roosterteeth.com (Podcast). Rooster Teeth Productions. Event occurs at 33:46. http://roosterteeth.com/podcast/episode.php?id=158. Retrieved 8/20/13.

- ↑ Muir, John Kenneth (2000). The Films of John Carpenter. McFarland. p. 54.

- ↑ "Dark Star - Benson, Arizona". Benzedrine.cx. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

External links

- Dark Star at the Internet Movie Database

- Dark Star at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dark Star at allmovie

- Dark Star at the TCM Movie Database

- Dark Star at The Official John Carpenter

- Script of the original short version of Dark Star

- AMC.com - B Movies - Dark Star (Full Streaming Movie)

| ||||||||||||||