Darcy's law

Darcy's law is a phenomenologically derived constitutive equation that describes the flow of a fluid through a porous medium. The law was formulated by Henry Darcy based on the results of experiments[1] on the flow of water through beds of sand. It also forms the scientific basis of fluid permeability used in the earth sciences, particularly in hydrogeology.

Background

Although Darcy's law (an expression of conservation of momentum) was determined experimentally by Darcy, it has since been derived from the Navier-Stokes equations via homogenization. It is analogous to Fourier's law in the field of heat conduction, Ohm's law in the field of electrical networks, or Fick's law in diffusion theory.

One application of Darcy's law is to water flow through an aquifer; Darcy's law along with the equation of conservation of mass are equivalent to the groundwater flow equation, one of the basic relationships of hydrogeology. Darcy's law is also used to describe oil, water, and gas flows through petroleum reservoirs.

Description

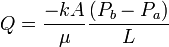

Darcy's law is a simple proportional relationship between the instantaneous discharge rate through a porous medium, the viscosity of the fluid and the pressure drop over a given distance.

-

'

'

The total discharge, Q (units of volume per time, e.g., m3/s) is equal to the product of the intrinsic permeability of the medium, k (m2), the cross-sectional area to flow, A (units of area, e.g., m2), and the total pressure drop (Pb - Pa), (Pascals), all divided by the viscosity, μ (Pa·s) and the length over which the pressure drop is taking place (m). The negative sign is needed because fluid flows from high pressure to low pressure. If the change in pressure is negative (where Pa > Pb), then the flow will be in the positive 'x' direction. Dividing both sides of the equation by the area and using more general notation leads

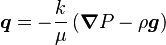

where q is the flux (discharge per unit area, with units of length per time, m/s) and  is the pressure gradient vector (Pa/m). This value of flux, often referred to as the Darcy flux, is not the velocity which the fluid traveling through the pores is experiencing. The fluid velocity (v) is related to the Darcy flux (q) by the porosity (n). The flux is divided by porosity to account for the fact that only a fraction of the total formation volume is available for flow. The fluid velocity would be the velocity a conservative tracer would experience if carried by the fluid through the formation.

is the pressure gradient vector (Pa/m). This value of flux, often referred to as the Darcy flux, is not the velocity which the fluid traveling through the pores is experiencing. The fluid velocity (v) is related to the Darcy flux (q) by the porosity (n). The flux is divided by porosity to account for the fact that only a fraction of the total formation volume is available for flow. The fluid velocity would be the velocity a conservative tracer would experience if carried by the fluid through the formation.

Darcy's law is a simple mathematical statement which neatly summarizes several familiar properties that groundwater flowing in aquifers exhibits, including:

- if there is no pressure gradient over a distance, no flow occurs (these are hydrostatic conditions),

- if there is a pressure gradient, flow will occur from high pressure towards low pressure (opposite the direction of increasing gradient - hence the negative sign in Darcy's law),

- the greater the pressure gradient (through the same formation material), the greater the discharge rate, and

- the discharge rate of fluid will often be different — through different formation materials (or even through the same material, in a different direction) — even if the same pressure gradient exists in both cases.

A graphical illustration of the use of the steady-state groundwater flow equation (based on Darcy's law and the conservation of mass) is in the construction of flownets, to quantify the amount of groundwater flowing under a dam.

Darcy's law is only valid for slow, viscous flow; fortunately, most groundwater flow cases fall in this category. Typically any flow with a Reynolds number less than one is clearly laminar, and it would be valid to apply Darcy's law. Experimental tests have shown that flow regimes with Reynolds numbers up to 10 may still be Darcian, as in the case of groundwater flow. The Reynolds number (a dimensionless parameter) for porous media flow is typically expressed as

-

.

.

where ρ is the density of water (units of mass per volume), v is the specific discharge (not the pore velocity — with units of length per time), d30 is a representative grain diameter for the porous media (often taken as the 30% passing size from a grain size analysis using sieves - with units of length), and μ is the viscosity of the fluid.

Derivation

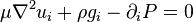

For stationary, creeping, incompressible flow, i.e.  , the Navier-Stokes equation simplify to the Stokes equation:

, the Navier-Stokes equation simplify to the Stokes equation:

-

,

,

where  is the viscosity,

is the viscosity,  is the velocity in the i direction,

is the velocity in the i direction,  is the gravity component in the i direction and P is the pressure.

Assuming the viscous resisting force is linear with the velocity we may write:

is the gravity component in the i direction and P is the pressure.

Assuming the viscous resisting force is linear with the velocity we may write:

-

,

,

where  is the porosity, and

is the porosity, and  is the second order permeability tensor. This gives the velocity in the

is the second order permeability tensor. This gives the velocity in the  direction,

direction,

-

,

,

which gives Darcy's law for the volumetric flux density in the  direction,

direction,

-

.

.

In isotropic porous media the off-diagonal elements in the permeability tensor are zero,  for

for  and the diagonal elements are identical,

and the diagonal elements are identical,  , and the common form is obtained

, and the common form is obtained

-

.

.

Additional forms of Darcy's law

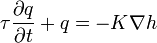

For very short time scales, a time derivative of flux may be added to Darcy's law, which results in valid solutions at very small times (in heat transfer, this is called the modified form of Fourier's law),

-

,

,

where τ is a very small time constant which causes this equation to reduce to the normal form of Darcy's law at "normal" times (> nanoseconds). The main reason for doing this is that the regular groundwater flow equation (diffusion equation) leads to singularities at constant head boundaries at very small times. This form is more mathematically rigorous, but leads to a hyperbolic groundwater flow equation, which is more difficult to solve and is only useful at very small times, typically out of the realm of practical use.

Another extension to the traditional form of Darcy's law is the Brinkman term, which is used to account for transitional flow between boundaries (introduced by Brinkman in 1949 [2]),

-

,

,

where β is an effective viscosity term. This correction term accounts for flow through medium where the grains of the media are porous themselves, but is difficult to use, and is typically neglected.

Another derivation of Darcy's law is used extensively in petroleum engineering to determine the flow through permeable media - the most simple of which is for a one dimensional, homogeneous rock formation with a fluid of constant viscosity.

-

,

,

where Q is the flowrate of the formation (in units of volume per unit time), k is the relative permeability of the formation (typically in millidarcies), A is the cross-sectional area of the formation, μ is the viscosity of the fluid (typically in units of centipoise, and L is the length of the porous media the fluid will flow through.  represents the pressure change per unit length of the formation. This equation can also be solved for permeability, allowing for relative permeability to be calculated by forcing a fluid of known viscosity through a core of a known length and area, and measuring the pressure drop across the length of the core.

represents the pressure change per unit length of the formation. This equation can also be solved for permeability, allowing for relative permeability to be calculated by forcing a fluid of known viscosity through a core of a known length and area, and measuring the pressure drop across the length of the core.

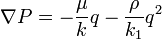

For very high velocities in porous media, inertial effects can also become significant. Sometimes an inertial term is added to the Darcy's equation, known as Forchheimer term. This term is able to account for the non-linear behavior of the pressure difference vs velocity data.[3]

,

,

where the additional term  is known as inertial permeability.

is known as inertial permeability.

Darcy's law is valid only for flow in continuum region. For a flow in transition region, where both viscous and Knudsen friction are present a new formulation is used, which is known as binary friction model [4]

,

,

where  is the Knudsen diffusivity of the fluid in porous media.

is the Knudsen diffusivity of the fluid in porous media.

See also

- The darcy unit of fluid permeability

- Hydrogeology

- Groundwater flow equation

Notes

- ↑ H. Darcy, Les Fontaines Publiques de la Ville de Dijon, Dalmont, Paris (1856).

- ↑ Brinkman, H. C. (1949). "A calculation of the viscous force exerted by a flowing fluid on a dense swarm of particles". Applied Scientific Research 1: 27–34. doi:10.1007/BF02120313.

- ↑ A. Bejan, Convection Heat Transfer, John Wiley & Sons (1984)

- ↑ Pant, Lalit M.; Sushanta K. Mitra, Marc Secanell (2012). "Absolute permeability and Knudsen diffusivity measurements in PEMFC gas diffusion layers and micro porous layers". Journal of Power Sources. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.01.099.