Daming Palace

| Daming Palace | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大明宫 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 大明宮 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Palace of Great Brilliance[1] | ||||||

| |||||||

| Daming Palace National Heritage Park | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大明宫国家遗址公园 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 大明宮國家遺址公園 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Daming Palace National Heritage Park | |

|---|---|

The reconstructed Danfeng Gate of the Daming Palace | |

| Established | 1 October 2010 |

| Location | Xi'an, China |

| Coordinates | 34°17′02″N 108°57′58″E / 34.284°N 108.966°E |

| Type | Archaeological site and history museum |

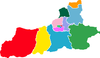

The Daming Palace ("Palace of Great Brilliance"[1]) was the imperial palace complex of the Tang Dynasty, located in its capital Chang'an.[2][3] It served as the royal residence of the Tang emperors for more than 220 years.[2] Today, it is designated as a national heritage site of China.[4] The area is located northeast of present-day Xi'an, Shaanxi Province.[5]

Name

The palace was originally known as Yong'an Palace, but was renamed to Daming Palace in 635.[6][7] In 662, after renovations to the palace, it was renamed to Penglai Palace.[6][7] In 670, it was named to Hanyuan Palace.[7] Eventually, in 701, the name of the palace became Daming Palace again.[6][7]

History

The former royal residence was the Taiji Palace, built in the previous Sui Dynasty.[8] In 632, Ma Zhou charged that the retired Emperor Gaozu was living in Da'an Palace (大安宮) to the west, which he considered an inhospitable place as it was built on low-lying lands of Chang'an that was plagued by dampness and heat during the summer.[9] According to him, ever since Emperor Taizong moved to the countryside during the summers, his retired father was left behind in Chang'an to suffer in the summer heat.[9] However, his father would always decline any invitation to spend the summer together when Emperor Taizong eventually did invite him.[9] Ever since the bloody palace coup of the Xuanwu Gate Incident in 626, it seemed that father and son had drifted apart to an extent that their relationship never healed.[9]

In 634, Emperor Taizong launched the construction of the Daming Palace at Longshou Plateau.[10][11] He ordered the construction of the summer palace for his retired father, Emperor Gaozu, as an act of filial piety.[12] However, Emperor Gaozu grew ill and never bore witness to the palace's completion before his death in 635,[9] so construction halted thereafter. Construction commenced once again in 662 after Empress Wu commissioned the court architect Yan Liben to design the palace in 660.[12] In 663, the construction of the palace was completed under the reign of Emperor Gaozong.[13] Emperor Gaozong had launched the extension of the palace with the construction of the Hanyuan Hall in 662, which was finished in 663. In 5 June 663, the Tang Dynasty imperial family began to relocate from the Taiji Palace into the yet to be completed Daming Palace,[14] which became the new seat of the imperial court and political center of the empire.[7][14][15]

Layout and function

Beginning from the south and ending in the north, on the central axis, stand the Hanyuan Hall, the Xuanzheng Hall, and the Zichen Hall.[6] These halls were historically known as the "Three Great Halls" and were respectively part of the outer, middle, and inner court.[6] The central southern entrance of the Daming Palace is the Danfeng Gate.[16] The gate consisted of five doorways.[17]

Outer court

After passing through the Danfeng Gate, there is a square of 630 meters long with at the end the Hanyuan Hall.[14] The Hanyuan Hall was connected to pavilions by corridors, namely the Xiangluan Pavilion in the east and the Qifeng Pavilion in the west.[6][18] The pavilions were composed of three outward-extending sections of the same shape but different size that were connected by corridors.[18] The elevated platform of the Hanyuan Hall is approximately 15 meters high, 200 meters wide, and 100 meters long.[5] The Hanyuan Hall, where many state ceremonies were conducted, would serve as the main hall for hosting foreign ambassadors during diplomatic exchanges.[5]

Middle court

The Xuanzheng Hall is located at a distance of about 300 meters north of the Hanyuan Hall.[6] State affairs were usually conducted in this hall.[19] The office of the secretariat was located to the west of the Xuanzheng Hall and the office of the chancellery was located to the east.[20] From this area, the department of state affairs, the chancellery, and the secretariat handled the central management of the Tang empire,[20] which was done in a system with Three Departments and Six Ministries.[20]

Inner court

The Zichen Hall, located in the inner court,[20] is approximately 95 meters north of the Xuanzheng Hall.[6] It housed the central government offices.[21] For officials, it was considered a great honor to be summoned to the Zichen Hall.[20] Taiye Lake,[ 1] named after the pond excavated by the Han emperor Wu during the construction of his Jianzhang Palace in the first century BC, is lies to the north of the Zichen Hall.[22] It expanded over 240 mu[23] (40 acres or 0.16 km²) and an island representing the mythical land of Penglai was built within it. The pond and island have been recreated, as have the former gardens. These were based on the historical record, with separate peony, chrysanthemum, plum, rose, bamboo, almond, peach, and persimmon gardens.[24]

The Linde Hall is located to the west of the lake.[21] It served as a place for banquets, performances, and religious rites.[25] It consisted of three halls—a front, middle, and rear hall—adjacent to each other.[25] An imperial park could be found north of the palace complex.[21] The Sanqing Hall was located in the northeast corner the Daming Palace and served as a Taoist temple for the imperial family.[21][22]

The border of the present site has also been planted with locusts and willows around all four sides.[24]

Heritage

The site of the Daming Palace was discovered in 1957.[14] Between 1959 to 1960, the earliest surveys and excavations of the Hanyuan Hall site were carried out by the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.[18]

Preventive conservation measures of the Hanyuan Hall site began in 1993.[5] From 1994 to 1996, for the restoration and preservation of the site, numerous surveys and excavations were conducted.[18] The State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) drew up and adopted a two-phased plan by 24 July 1995 to safeguard the Hanyuan Hall site.[5][14] Work on the project started in 1995 by the joint effort of the Chinese government, Chinese and Japanese institutes, UNESCO, and various specialists.[26] Most of the conservation work concluded in 2003.[5][26]

On 1 October 2010, the Daming Palace National Heritage Park was opened to the public.[27] There are many exhibition halls located throughout the site of the palace complex to showcase the excavated cultural relics of the site.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chung, Saehyang. "A Study of the Daming Palace: Documentary Sources and Recent Excavations". Artibus Asiae, Vol. 50, No. 1/2 (1990), pp. 23-72. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Yu, Weichao (1997). A Journey into China's antiquity. Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers. p. 56. ISBN 978-7-5054-0507-3.

- ↑ "Stories of Daming Palace". China Daily. p. 2. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ Wang, Tao; Shao, Lei (2010). "Eco-city: China's realities and challenges in urban planning and design". In Lye, Liang Fook; Chen, Gang. Towards a liveable and sustainable urban environment: Eco-cities in East Asia. Singapore: World Scientific. p. 149. ISBN 978-981-4287-76-0.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Du, Xiaofan; Hellman, Naomi (translator) (2010). Agnew, Neville, ed. Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 "Daming Palace". ChinaCulture.org. Ministry of Culture of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Daming Palace Site". Cultural China. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Birth of fantasy" (in English). Daming Palace. Episode 1. 7 minutes in. China Central Television. CCTV-9. http://english.cntv.cn/program/documentary/20111118/100113.shtml.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Wenchsler, Howard J. (1979). "The founding of the T'ang dynasty: Kao-tsu (reign 618–26)". The Cambridge history of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-521-21446-7.

- ↑ Chen, Jack W. (2010). The poetics of sovereignty: On Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-674-05608-4.

- ↑ Kiang, Heng Chye (1999). Cities of aristocrats and bureaucrats: The development of medieval Chinese cityscapes. Singapore: Singapore University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-9971-69-223-0.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The missing ancient architectures Part 3- Eternal regrets of the Daming Palace". China Central Television. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ Fuller, Michael A. (1990). The road to East Slope: The development of Su Shi's poetic voice. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8047-1587-4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 "Birth of fantasy" (in English). Daming Palace. Episode 1. 24 minutes in. China Central Television. CCTV-9. http://english.cntv.cn/program/documentary/20111118/100113.shtml.

- ↑ "Conference 'Daming Palace and the Tang Dynasty'". Oxford Archaeology. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Site of Danfeng Gate". ICOMOS International Conservation Center. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ "Archaeologists find ancient palace gate". ABC News. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Hanyuan Hall of Daming Palace, Beijing: UNESCO Beijing Office, 1998

- ↑ "Birth of fantasy" (in English). Daming Palace. Episode 1. 37 minutes in. China Central Television. CCTV-9. http://english.cntv.cn/program/documentary/20111118/100113.shtml.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "Birth of fantasy" (in English). Daming Palace. Episode 1. 39-41 minutes in. China Central Television. CCTV-9. http://english.cntv.cn/program/documentary/20111118/100113.shtml.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Daming Palace". AncientWorlds LLC. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Original site of Daming Palace". China Daily. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ China Bravo. "Daming Palace National Heritage Park". Accessed 15 November 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 China Daily. "Brief Introduction of Daming Palace National Heritage Park". 2010. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Linde Hall". Cultural China. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Hanyuan Hall of the Daming Palace of the Tang Dynasty, China". Permanent Delegation of Japan to UNESCO. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Daming Palace preservation project". China Daily. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daming Palace. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||