Dabigatran

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| Ethyl 3-{[(2-{[(4-{N'-hexyloxycarbonyl carbamimidoyl}phenyl)amino]methyl}-1-

methyl-1H-benzimidazol-5-yl)carbonyl] (pyridin-2-yl-amino)propanoate | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Pradaxa,Prazaxa |

| MedlinePlus | a610024 |

| Licence data | EMA:Link, US FDA:link |

| Pregnancy cat. | C (US) |

| Legal status | Schedule VI (CA) POM (UK) ℞-only (US) |

| Routes | oral |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 3–7%[1] |

| Protein binding | 35%[1] |

| Half-life | 12–17 hours[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 211915-06-9 |

| ATC code | B01AE07 |

| PubChem | CID 6445226 |

| DrugBank | DB06695 |

| ChemSpider | 4948999 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL539697 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C34H41N7O5 |

| Mol. mass | 627.734 g/mol |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

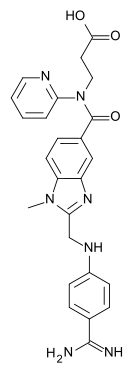

| |

|---|---|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 3-({2-[(4-Carbamimidoyl-phenylamino)-methyl]-1-methyl-1H-benzoimidazole-5-carbonyl}-pyridin-2-yl-amino)-propionic acid | |

| Clinical data | |

| Legal status | ? |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 211914-51-1 |

| ATC code | ? |

| PubChem | CID 216210 |

| ChemSpider | 187412 |

| UNII | I0VM4M70GC |

| KEGG | D09707 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL48361 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C25H25N7O3 |

| Mol. mass | 471.511 g/mol |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Dabigatran (Pradaxa in Australia, Europe, USA and Canada (previously was Pradax in Canada, name change to Pradaxa as of January 2013), Prazaxa in Japan) is an oral anticoagulant drug that acts as a direct thrombin (factor IIa) inhibitor. It was developed by the pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim.

Dabigatran can be used for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. The drug was developed as an alternative to warfarin, since it does not require maintenance of international normalized ratio or monitoring by frequent blood tests, while offering similar efficacy in preventing ischemic events. Unlike warfarin,[2] there is currently no way to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in the event of clinically significant bleeding.[3][4]

Medical uses

Dabigatran can be used to prevent strokes in those with atrial fibrillation due to causes other than heart valve disease, and at least one additional risk factor for stroke (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, and prior stroke),[5] Patients already taking warfarin with excellent international normalized ratio (INR) control may have little to gain by switching to dabigatran in atrial fibrillation.[6] In practice, warfarin remains the standard drug for patients with atrial fibrillation and a moderate or high risk of thrombosis. Aspirin is an alternative for low-moderate-risk patients.[7] When the risk is significant and the INR cannot be maintained within the target range despite close monitoring, dabigatran is the alternative to warfarin, provided the patient is closely monitored, especially for changes in renal function,[8] adverse events (bleeding) and discontinuation.[9] A systematic review of new anticoagulants states the treatment benefits of dabigatran and other new anticoagulants compared with warfarin are small and vary depending on the control achieved by warfarin treatment.[9] In February 2011, the American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association added dabigatran to their guidelines for management of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with a class I recommendation, level of evidence: B. Warfarin had a class 1A recommendation.[6] Also the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) gives a prominent place to the new anticoagulants for non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the 2012 update of her guidelines: "where oral anticoagulation is recommended to consider one of the NOACs (new oral anticoagulants) rather than adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonists for most patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, based on their net clinical benefit".[10]

Dabigatran can also be used to prevent the formation of blood clots in the veins (deep venous thrombosis) in adults who have had an operation to replace a hip or knee.[11] LMWH (low molecular weight heparin) and warfarin are the standard drugs for prevention of recurrences of deep venous thrombosis . LMWH and warfarin have similar harm-benefit balances. There is no evidence that rivaroxaban or dabigatran has a better harm-benefit balance than warfarin for long-term treatment.[12] Direct thrombin inhibitors are as effective in the prevention of major venous thromboembolism in THR or TKR as LMWH and vitamin K antagonists. However, they show higher mortality and cause more bleeding than LMWH.[13] New oral anticoagulants are effective for thromboprophylaxis after total hip repair and total knee repair. Their clinical benefits over LMWH are marginal and offset by increased risk for major bleeding. There is no evidence that new anticoagulants have a better harm-benefit balance than LMWH. They have not been compared with warfarin in hip and knee operations.[14] The use of once-daily enoxaparin regimen as control in clinical trials will lead to more favorable estimates of relative efficacy for the new oral anticoagulants than if enoxaparin 30 mg bid had been chosen as a comparator.[15] In a systematic review of three trials, novel anticoagulants did not differ from warfarin for mortality or venous thromboembolism related mortality in prevention of venous thromboembolism.[9]

Off-label uses

In the US only 63% of all dabigatran treatment visits in the last quarter of 2011 were for atrial fibrillation. The rest was for off-label uses. The most common off-label uses of dabigatran in the last quarter of 2011 were coronary artery disease (7% vs 6% in the last quarter of 2010), hypertensive heart disease (9% vs 7% in 2010), and treatment of venous thromboembolism (18% vs 15% in 2010).[16]

The addition of the new oral anticoagulants to single or dual antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary syndrome results in a modest reduction in cardiovascular events but a substantial increase in bleeding, most pronounced when new oral anticoagulants are combined with dual antiplatelet therapy (triple therapy).[17][18] For acute treatment of venous thromboembolism Dabigatran is not indicated. It requires 5–7 days of initial heparin treatment.[19] There is no proof of benefit for dabigatran in hypertensive heart disease without atrial fibrillation.

Development

Dabigatran (then compound BIBR 953) was discovered from a panel of chemicals with similar structure to benzamidine-based thrombin inhibitor α-NAPAP (N-alpha-(2-naphthylsulfonylglycyl)-4-amidinophenylalanine piperidide), which had been known since the 1980s as a powerful inhibitor of various serine proteases, specifically thrombin, but also trypsin. Addition of ethyl ester and hexyloxycarbonyl carbamide hydrophobic side chains led to the orally absorbed prodrug, BIBR 1048 (dabigatran etexilate).[20]

Mechanism of action

Ingested orally, dabigatran is a competitive and reversible direct thrombin inhibitor.[21]

Thrombin plays a role in the last step of blood coagulation, being composed of one active site and two secondary binding exosites. The first exosite aids active site binding through docking substrates such as fibrin, whilst the second binds heparin. Dabigatran thus inactivates both fibrin-bound and free thrombin through binding to the active site; proving more effective than indirect thrombin inhibitors such as unfractionated heparin (which cannot inhibit fibrin-bound thrombin).[22]

Adverse effects

According to a systematic review, adverse effects of new anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban) compared with warfarin were lower for fatal bleeding and haemorrhagic stroke, numerically lower for major bleeding, numerically higher for gastrointestinal bleeding, and higher for discontinuation due to adverse events. Bleeding risks may be increased for persons older than 75 years or those receiving warfarin who have good control. The review was limited by absence of head-to-head comparisons of NOACs (new oral anticoagulants) and by limited data on harms.[9]

In the Re-Ly trial, warfarin had more risk of intracranial bleeding absolute risk reduction (ARR) 1% for dabigatran] and hospitalizations (ARR 1.6% for dabigatran), and dabigatran had more risk of heart attack absolute risk increase (ARI) 0.4%, gastrointestinal bleeding (ARI 0.6%) and withdrawal because of serious adverse effect (ARI 1%) or withdrawal because of any adverse effect (ARI 4.1%).[23] Also there was a numerically increased risk of lung embolism, most for high dose dabigatran.[24] The most frequent adverse reactions leading to discontinuation of Pradaxa were bleeding and gastrointestinal events.[25]

But comparing risks of warfarin to dabigatran if INR control is adequate (as in Northern and West-Europe), the total bleeding risks (major bleeding) are equal and for the elderly ≥ 75 years the risk for major bleeding of dabigatran was significantly higher.[11]

Haemorrhage

The most common side effect of dabigatran, seen in more than one patient in 10, is bleeding.[11] There is a 58% higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding for dabigatran compared to standard care; but it is also a problem for rivaroxaban (48% higher), and maybe for all new anticoagulants. Combined in all studies of new anticoagulants there was a 45% higher risk; the lowest numerical risk increase was for apixaban and edoxaban.[26]

In RE-LY when compared to warfarin, patients taking dabigatran had fewer life-threatening bleeds and fewer minor and major bleeds, including intra cranial bleeds, but the rate of GI bleeding was higher, mostly in older patients over 75 years. In patients over 75 years, extra cranial major bleeding risk was higher for high-dose dabigatran compared to warfarin.[27]

A randomised trial comparing dabigatran with warfarin, and 5 studies of several hundred serious bleeding events, identified factors that increased the risk of bleeding. They included even mild renal failure, age over 75 years, body weight less than 60 kg, switching between anticoagulants, opening the dabigatran capsules before ingestion, and concomitant use of drugs that interact with dabigatran. A dabigatran dose below 220 mg per day does not protect patients from the risk of haemorrhage.[28]

Concomitant use of anti-platelet agents increases the risk of major bleeding with dabigatran approximately two-fold, therefore a careful benefit-risk assessment should be made prior to initiation of treatment.[29] In the RE-LY trial concomitant use of a single anti-platelet seemed to increase the risk of major bleeding 60% (HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.42–1.82); dual anti-platelet seemed to increase this even more 131% (HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.79–2.98).[30] SSRIs and SNRIs, both antidepressants, increased the risk of bleeding in RE-LY in all treatment groups.[31]

Gastrointestinal upset

In the RE-LY trial, the most commonly reported side effect of dabigatran was gastrointestinal upset. Dabigatran capsules contain tartaric acid, which lowers the gastric pH and is required for adequate absorption. The lower pH has previously been associated with dyspepsia; this may play a role in the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding,[32] and in the high rate of discontinuation, which can lead to stroke.

Overdose

There is currently no way to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in the event of clinically significant bleeding.[3][4]

The lack of a reliable blood test to monitor dabigatran makes it difficult to determine if a given patient is experiencing a drug interaction.[33] Testing of anticoagulant activity may be required in specific circumstances, such as surgery, overdose and bleeding. In patients treated with dabigatran, rivaroxaban or apixaban, changes in the INR test (international normalised ratio) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) do not correlate with the dose and should not be performed. In early 2013, there is still no routine coagulation test suitable for monitoring these patients; specific tests are only available in specialised laboratories.[34]

Heart attack risk

A significantly increased risk (33%-46%) of myocardial infarction (heart attacks) and acute coronary syndrome has been noted when combining the safety outcome data from multiple trials.[35][36] In another meta analysis the oral direct thrombin inhibitors were associated with significantly higher rates (RR 32-35%) for myocardial infarction as compared to warfarin.[37][38] In a systematic review of all new anticoagulants, subgroup analyses suggested a higher risk for myocardial infarction for direct thrombin inhibitors like dabigatran compared to FXa inhibitors like rivaroxaban and apixaban.[9]

Long term safety

The safety (and efficacy) of dabigatran and other thrombin inhibitors in the longer term (beyond two years) are uncertain.[39]

Drug interactions

Concomitant administration of a P-gp inducer, such as rifampicin, St Johns wort (Hypericum perforatum), carbamazepine (Tegretol), or phenytoin is expected to result in decreased dabigatran concentrations and should be avoided.[11]

Drug excretion through P-glycoprotein pumps is slowed in patients taking strong p-glycoprotein pump inhibitors, such as quinidine, verapamil (Isoptin), clarithromycin (Zitromax) and amiodarone (Cordarone), thus raising plasma levels of dabigatran.[40] Dosing should be reduced.

Taking long term anti-platelet drugs as aspirin or clopidogrel (Plavix) doubled the incidence of major bleeding events. This effect is similar for both doses of dabigatran and for warfarin.[41] Taking long term NSAIDs can cause more bleeding episodes;[42][43] antidepressants such as SSRIs and SNRIs can also interact with Dabigatran.[31]

Switching from warfarin to dabigatran

In real life switching from warfarin to dabigatran can be risky: thromboembolic risk associated with dabigatran was 250% to 470% higher for low and high dose dabigatran than with warfarin.[44] No such risk was reported in the Re-Ly trial, in which 50% of patients switched from long-term warfarin treatment to dabigatran. There was also an increased risk of bleeding when switching from warfarin to a 110 mg dose of dabigatran. In the first two months after switching there was also a 200% increased risk of myocardial infarction.[45]

Discontinuation

Patients with atrial fibrillation should not stop taking Pradaxa without talking to their healthcare professional. Stopping use of blood thinning medications can increase their risk of stroke.[46] For this reason the pradaxa label now carries a boxed warning in the US, similar to the labels of other new oral anticoagulants,[47] not like warfarin that has a boxed warning because of serious bleeding risk. Albeit major bleeding risk is not significantly different between warfarin and new oral anticoagulants.[9]

In real life discontinuation can be quite high. In a US study 40% of patients discontinued dabigatran therapy within 6 months, and the majority of these patients were not anticoagulated with warfarin upon discontinuation.[48]

Contraindications

Dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min), to minimise the risk of bleeding.

Dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with active pathological bleeding and must not be used in patients who have lesions or conditions at significant risk of major bleeding such as current or recent gastrointestinal ulceration, recent brain or spinal injury or surgery, recent ophthalmic surgery, recent intra-cranial haemorrhage, etc. It is contraindicated in hepatic impairment or liver disease expected to have any impact on survival.[49]

Pradaxa is contraindicated in patients with prosthetic heart valve requiring anticoagulant treatment, after studies found increased rate of thromboembolic events and bleeding events in those on dabigatran vs those on warfarin.[50] Pradaxa is not indicated for valvular heart disease as mitral stenosis, because there is minimal data available.[51]

Pradaxa must not be used in patients taking medicines against mycosis, either by mouth or injection, ketoconazole (Nizoral) and itraconazole (Sporanox), the immunosuppressant medicines cyclosporine and tacrolimus or the anti-arrhytmic quinidine or dronedarone (Multaq).[52] Use of dabigatran is contraindicated with other anticoagulants, like warfarin or enoxaparin, except when switching treatment to or from dabigatran, or with the use of unfractionated heparin for maintenance of venous or arterial catheter patency.

Dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with a known serious hypersensitivity reaction (e.g., anaphylactic reaction or anaphylactic shock).

The use of dabigatran during pregnancy or lactation is not recommended. There is currently no experience of new oral anticoagulants (rivaroxaban, apixaban, betrixaban or dabigatran) use in pregnancy.[53]

Dosing

For patients who have had a hip or knee replacement, treatment with Dabigatran should start with one 110-mg capsule taken one to four hours after the end of the operation. Treatment then continues with 220 mg (as two 110-mg capsules) once a day for 28 to 35 days after hip replacement and for 10 days after knee replacement. A lower dose is used in patients with moderate kidney problems, in patients over 75 years of age, and in patients also taking amiodarone (Cordarone), quinidine or verapamil (Isoptin) (medicines used to treat heart problems).

For the prevention of strokes and blood clots in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, Dabigatran is taken at a dose of 300 mg (as one 150 mg capsule twice a day) and should be taken long term. A lower dose is used in patients with moderate kidney problems who are at high risk of bleeding, patients aged over 80 years, and patients also taking verapamil. A lower dose may also be used in patients aged 75 to 80 years who are at high risk of bleeding. All patients considered to be at risk of bleeding should be monitored closely and the dose of Dabigatran lowered at the discretion of the doctor.[11]

In the US, a dose of 150 mg twice daily was approved for patients with a creatinine clearance >30 ml/min, whereas in patients with severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance 15 to 30 ml/min) the approved dose is 75 mg twice daily, a dose currently marketed in the European Union, but not evaluated in the RE-LY trial. The 110-mg, twice–daily dose used in the trial did not receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[6]

Dabigatran has a half-life of about 12-14 h, and exerts a maximum anticoagulation effect within 2-3 h after ingestion.[54]

Drug excretion through P-glycoprotein pumps is slowed in patients taking strong p-glycoprotein pump inhibitors, such as verapamil (Isoptin) and amiodarone (Cordarone), thus raising plasma levels of dabigatran.[40] Dosing should be reduced to 150 mg taken once daily in patients who receive concomitantly dabigatran etexilate and those P-gp inhibitors.[55]

The capsule should not be opened before taking the dose (such as sprinkling the contents of the capsule on food) because the amount of drug absorbed is substantially increased.[33]

Once a bottle of dabigatran is opened, the medication expires after four months,because the drug can be affected by humidity. The bottle cap contains a desiccant to reduce the humidity and prevent degradation of the drug. Blister packs do not have that same four-month expiration.[56]

Pivotal trials for authorisation

The RE-LY study: prevention of ischaemic stroke in avalvular atrial fibrillation

For understanding trials of new oral anticoagulants in avalvular atrial fibrillation (rivaroxaban ROCKET AF trial, apixaban ARISTOTLE trial and edoxaban ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48) it is essential to understand the RE-LY trial.

The RE-LY trial is a Boehringer Ingelheim, phase III study. It evaluated the efficacy and safety of two different doses of dabigatran relative to warfarin in over 18,000 patients with atrial fibrillation. They were randomized to one of three arms: (1) adjusted dose warfarin, (2) dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, or (3) dabigatran 150 mg twice daily. The warfarin arm was open label, but adverse events were adjudicated by reviewers blinded to treatment.

Dabigatran 110 mg was not inferior to warfarin for the primary efficacy endpoint of stroke or systemic embolization, while dabigatran 150 mg was significantly more effective than warfarin or dabigatran 110 mg. [57] Analyses by EMA demonstrated the benefits observed in the comparison of dabigatran to warfarin diminished if INR control was good, with time in therapeutic range TTR >70%.[11][58] In Re-ly INR values were within the target range 64.4% of the time.[24] In other trials with new anticoagulants mean TTR (Time in Therapeutic Range) was only 55% in ROCKET for rivaroxaban, 62% in ARISTOTLE for apixaban, 66% in SPORTIF 3 for meligatran, median (not mean) TTR was 68,4% in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 for edoxaban. On the contrary in AuriculA, the Swedish national quality registry for atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation the mean TTR for all patients was 76.2%.[59]

Major bleeding occurred significantly less often with dabigatran 110 mg than warfarin; dabigatran 150 mg showed similar major bleeding to warfarin.[57][60] The global INR control in RE-LY, although being comparable to contemporary trials in this indication, was not optimal from a Northern/Western European standard. When major bleeding events were analysed by time in therapeutic range (TTR), the outcome of warfarin treatment for the overall population improved with increasing TTR. For centres with TTR ≥ 70% (such as Western Europe) the major bleeding event rates were marginally higher for dabigatran 150 twice a day vs. warfarin, and for the elderly ≥ 75 years the risk was significantly higher.[11]

A post hoc analysis from RE-LY showed patients over 75 with atrial fibrillation at risk for stroke have lower risks of intra-cranial bleeding but higher risk of extra-cranial (gastrointestinal) bleeding with high-dose dabigatran when compared with warfarin.[27]

At the beginning of the trial approximately 40% of patients took aspirin and 7% took clopidogrel. Taking either anti-platelet drug doubled the incidence of major bleeding events, an absolute increase of > 2% per year. This effect was similar for both doses of dabigatran and for warfarin.[23] A favourable risk–benefit ratio for the use of aspirin (in terms of reduction in vascular events, including stroke) with warfarin has been reported only for patients with mechanical heart valves,[61] not for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.[62] In practice physicians do not co-prescribe anticoagulants and aspirin because of risk of bleedings. In other trials with new anticoagulants as in ARISTOTLE for apixaban 30,5% took aspirin, in the ROCKET-AF trial for rivaroxaban 38,5% and in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 for edoxaban 29%. But in the real world pan-European PREFER in AF registry only 10% took combined anticoagulant anti-platelets therapy, and only 0,5% needed them, not being given because of recent stenting or acute coronary syndrome event. Only 1,3% of the PREFER cohort received triple combined therapy, of wich only 0,6% had an appropriate indication .[63]

Apart from inadequate warfarin treatment, high antiplatelets consumption in RE-LY leaded to high rates of major bleeds in warfarin-treated patients, despite being a low-risk population, and the rates of major bleeds were higher than historic warfarin trials. The rate in RE-LY was 3,36% a year, and 3,57% a year, after revision of data.[24] This was much higher than in the meta-analyses with RCTs about warfarin and atrial fibrillation 1.3% [64][65][66] and than in real world, prospective studies from Sweden 1,6% and 2,6% a year [67][68] and The Netherlands 2,9% a year.[69] The rate of major bleeding in RE-LY is much higher than previously reported by the same author (1.78 to 2.92%) and than reported for warfarin groups in clinical trials of anticoagulants such as ximelagatran (1.8%) and idraparinux (1.4%).[57] This effect was expected because in an analysis of the SPORTIF 3 and 5 trials in 2006 aspirin combined with warfarin was associated with an incremental rate of major bleeding of 1.6% (P=0,01) per year against warfarine alone, whilst there was no incremental risk for ximelagatran.[70]

Also in trials with other NOACS (new oral anticoagulants) the rates of major haemorrhages were clearly higher than in older warfarin studies. They were 3.45% a year in ROCKET (rivaroxaban study), 3.36% in RE-LY (dabigatran study ), 3.09% in ARISTOTLE (apixaban study), and 3,43% in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (edoxaban study) against the BAFTA-study 1.6%,[71] the ACTIVE-W-study 2.21% [72] or in the earlier meta-analyses with RCTs about atrium fibrillation 1.3% and 1% for controle treatment.[64][65][66]

Intracranial hemorrhages were significantly fewer with dabigatran compared to warfarin. But in RE-LY, an unusually high incidence of intra-cranial haemorrhages by warfarin occurred, 0.76% per year, which is much more than meta-analyses from cochrane 0.3% and 0.45% or individual trials 0.53% in SPORTIF III (10% aspirine, multicenter world) and 0.28% in SPORTIF V (18,5% aspirin use, multicenter Northern-America).[23] Also in other multicenter world trials with new oral anticoagulants risk was higher: risk for warfarin in ROCKET AF was 0,7% per year, in ARISTOTLE 0,8% per year and in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 0,85% per year. Already in 1999, a meta-analysis found the use of aspirin with oral anticoagulants was associated with more than double the frequency of intra-cranial haemorrhage (relative risk = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.2-4.8, p = 0.02).[73] In 2004, a retrospective cohort analysis found that major bleeding events during 90 days after discharge for ventricular fibrillation occurred 46% more (almost significantly) in combined warfarin anti-platelet therapy against warfarin only. The major difference was seen in intra-cranial haemorrhage, which occurred three times more frequently in the combined group.[74] In RE-LY, independent predictors of intra-cranial haemorrhage were assignment to warfarin, aspirin use, age and previous stroke/transient ischemic attack. Concomitant aspirin use was the most important modifiable independent risk factor for intra-cranial haemorrhage.[75] The combined risk of aspirin with warfarin was not stated, although very relevant.

The fatality rate of haemorrhages after a first major bleeding event in 5 phase 3 trials of dabigatran was favourable for dabigatran: 9% against 13% for warfarin. In contrast the case fatality rate of bleeding events from dabigatran reported to the FDA was inverse: 16% against 8% for warfarin. The author works out that if fewer than 1 in 3 adverse bleeding events were reported to the FDA, this fatality rate may signal an increased risk for bleeding death compared with that seen in RE-LY. Anyway the FDA reporting system suffers from reporting bias and accuracy and duplication problems, so that any definitive conclusions can be drawn. The study suggests the drug is being used in a different profile of patients as that in the RE-LY trial: the mean age of patients who had an adverse event with dabigatran reported to the FDA (75 years) was greater than that in the RE-LY trial (71 years), and more patients with FDA-reported events were female (48%) than those included in RELY (36.7%).[76]

Dabigatran trended to decreased mortality compared to warfarin. The FDA clinical reviewer found the trend toward increased mortality with warfarin was entirely due to investigator sites where INR monitoring was inferior. At sites where INR was within therapeutic range ≥ 67% of the time, relative risk for mortality (RR 1.05) favoured warfarin over dabigatran.[23][77] Overall in the RE-LY study annual mortality rate was 3.84%. Cardiac deaths (sudden cardiac death and progressive heart failure) accounted for 37.4% of all deaths, whereas stroke and haemorrhage-related deaths represented only 9.8% of the total mortality. The majority of deaths (90%) are not related to stroke in a contemporary anti-coagulated AF population. These results emphasize the need to identify interventions beyond effective anticoagulation, in order to further reduce mortality in atrial fibrillation and that antithrombotic therapy only modestly reduces mortality in atrial fibrillation. Thus management of CV co-morbidities (heart failure, intra-ventricular conduction delay, diabetes mellitus, obesitas and renal impairment) may be more effective.[78] In a meta-analysis NOACs decreased all-cause mortality significantly in AF with 12%.[9]

Significantly more patients withdrew from dabigatran, due to serious adverse events (RRI 56%) and to any adverse event (RRI 26%), compared to warfarin and significantly more adverse events occurred with dabigatran (RRI 3%) compared to warfarin. There was 100% more dyspepsie with dabigatran. Absolute numbers of serious adverse events were not reported.[23] Because total serious adverse events include benefit and harm, total % serious adverse events provides a useful single measure of the overall health impact of a particular intervention.[79] In a meta analysis of 3 new oral anticoagulants discontinuation due to adverse events was significantly increased by 23% against warfarin and there were limited data on harms.[9]

There were significantly more heart infarctions (RRI 33% ARI 0,4%) in the initial analysis of the RE-LY trial.[23] A meta analysis confirmed that the oral direct thrombin inhibitors were associated with significantly higher rates (RRI 32-35%) for myocardial infarction as compared to warfarin.[37][38]

In the Re-ly study health-related quality of life was equal in warfarin and dabigatran treated patients who didn't experience strokes or bleedings. This was unexpected given the known complexities of warfarin treatment.[80]

Exclusion criteria included severe heart-valve disorder, stroke within 14 days or severe stroke within 6 months, conditions that increase risk for hemorrhage, creatinine clearance < 30 ml/min, active liver disease, and pregnancy.[57]

Some reviewers argue, because of major flaws in RE-LY, a double-blinded trial should be performed testing dabigatran against warfarin to verify the results of the RE-LY trial.[23][66] A meta analysis about the impact of double-blind vs. open study design on the observed treatment effects of new oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation found a significant 67% enhancement of treatment effect with PROBE/open-label trials compared with double blind trials (interaction test, P = 0.05) for hemorrhagic stroke. No other interaction was significant.[81] There are doubts about the netto clinical effect of dabigatran in the absence of data concerning total adverse events.[82] Other authors raise concerns about the design of the RE-LY trial, including selection bias (low risk patients), co-interventions (aspirin), adverse events (myocardial infarction) and generalisability (overrepresentation of stroke, underrepresentation of myocardial infarction) al leading into a bias in favour of dabigatran, causing its benefit to be overstated when generalising to a broader population.[83] The same selection bias including low risk patients was present in the ARISTOTLE trial. Co-interventions with aspirin and problems with generalisability bij overrepresentation of stroke and underrepresentation of myocardial infarction were present in ARISTOTLE, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 and ROCKET AF trials. In ARISTOTLE the ratio of previous stroke against previous myocardial infarction was 19,5% against 14% of participants, in ROCKET AF the ratio was 55% against 17% and in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 the ratio was 28,3% against 11,5%. In a real world population there is more myocardial infarction than stroke.[84][85][86] Another factor favourising dabigatran (and other NOACs) was seen by EMA reviewers pointing to inadequate warfarin control in much trial centers, considering North- and Western-European standards.[11] The same problem was seen in the rivaroxaban[87] and the apixaban study.

RE-COVER: prevention of venous thromboembolism

A 2009 Boehringer Ingelheim, randomized, double-blind trial by the RE-COVER study group demonstrated no inferiority of dabigatran 150 mg twice daily compared to warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism for prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism, with a similar rate of major bleeding after 6 month. Both groups received first 9 days of LWMH. Patients randomized to dabigatran had more dyspepsia and more drug discontinuation.[88]

Novel anticoagulants: advantages and disadvantages

Novel anticoagulants have some advantages. They have a more predictable anticoagulant response, absence of food interactions, and limited drug interactions compared with warfarin. As a result, monitoring of anticoagulant effect seems to be unnecessary. The half-life periods of these agents are also shorter than that of warfarin, a potential benefit if major bleeding was to occur. They have either renal or mixed renal/liver elimination/metabolism, allowing a clinician to choose a particular drug to meet the patients' comorbid conditions.

They have also some drawbacks, whose impact on real-world outcomes is not known. Because of their short half-life periods in combination with the fact that they do not require routine coagulation monitoring, the issue of medication adherence can become problematic. This can lead in real life to increased strokes and health costs. The lack of a simple coagulation assay to accurately measure the biological effect of new agents is another concern, in case of stroke, bleedings or urgent surgery. Moreover, there is no antidote or well-established procedure for reversing anticoagulation in emergent situations. Also, cost can be a disadvantage.[89]

Controversy: first- or second-line

Based on differing risk/benefit estimates, there are divergent opinions on whether dabigatran and the new oral anticoagulants should be a first- or a second-line treatment for non-valvular atrial fibrillation.[90] Cardiologic societies as The European Society of Cardiology and The American Heart Association adhere the first line approach for new oral anticoagulants (NOACS).[6][10] The British NICE considers both warfarin and NOACS dabigatran and rivaroxaban as first line treatments.[91] Independent pharmacotherapeutic and general medicine associations as Préscrire, The Dutch College of General Practitioners, The Australian Guidelines still adhere a first line approach for warfarin.[34][92] In an editorial The Cochrane Library advises caution in implementing these drugs into clinical practice. First, because of warfarin may be equally effective and as safe as NOACs in settings with well-organised anticoagulation clinics. Second, because in the absence of the need to visit anticoagulation clinics compliance with NOACs may be compromised. Such non-compliance may put patients at risk of thromboembolic events. Third, because there is currently no antidote against factor Xa inhibitors. This may be life-threatening in trauma patients or may pose difficulties in patients who need emergency surgery. Fourth, because cost-effectiveness analyses show that compared with warfarin new oral anticoagulants have high incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICERs). In countries with high-quality anticoagulation clinics ICERs are likely to be higher. Whether factor Xa inhibitors with such ICERs are affordable outside high-income countries is debatable.[93] The Health Council of the Netherlands advised that the introduction of the new oral anticoagulants must be accompanied by more detailed research into their safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness. They declared that considerable uncertainties still persist about the safety of these drugs. For example, the population that will be treated in everyday practice differs from the population taking part in the clinical trials. Also there is (still) no antidote with which the anticoagulant effect can be stopped in emergency situations. And due to the absence of frequent checks, the risk of poor compliance with the treatment in some of the patients is considerable, directly leading to serious consequences. They plead for a well-dosed introduction.[94] An Australian government commissioned report by prof Samson about atrial fibrillation concluded that the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme listing of NOACs should be a restricted benefit for patients unable to tolerate warfarin therapy and/or who are unable to obtain satisfactory INR control despite specific measures. Also that the cost-effectiveness and safety of the medications were still in doubt following fresh data on how dabigatran works in real life settings, compared with clinical trial evidence.[95]

Controversy: under-treatment or over-treatment with anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation

A 2009 prospective study concluded the net clinical benefit of warfarin was essentially zero in CHADS(2) stroke risk categories 0 and 1 (low and moderate risk), leading to potential overuse of warfarin in low and moderate risk categories (at least half of patients with atrial fibrillation).[96][97]

A 2010 Bayer healthcare UK sponsored systematic review concluded that there was under use of anticoagulants in high risk patients with atrial fibrillation. In 7 of 9 studies in patients with a CHADS2 score >or=2 treatment levels with anticoagulants were reported below 70% (range 39%-92.3%) and were "suboptimally treated".[98]

In the Danish Stroke Registry 17.1% of ischaemic stroke patients (7.482) had atrial fibrillation. Oral anticoagulation prescription rates were increasing, and in 2011 46.6% were prescribed oral anticoagulants, 42.5% had a contraindication, and 3.7% were not prescribed OAC without a stated contraindication. Contraindications were generally present in patients not in therapy, and the assumed under use of oral anticoagulants may be overestimated. This raises the question if alleged under-use of oral anticoagulants really is of the previously assumed size or could for a majority be explained by contraindications and risk/benefit ratios made by clinicians on an individual patient level. Advanced age, severe stroke, female gender, institutionalization, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption were associated with lower oral anticoagulation rates.[99]

Stroke risk prediction tools including the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASC models are helpful in clinical practice. However, these are limited within the context of complex cardiogeriatric syndromes. Expanding such models to consider frailty, cognitive and functional decline, or non-adherence to anticoagulant therapy is warranted. Although avoiding stroke is an important consideration, the potential adverse effects of treatment needs to be balanced within the context of best available evidence.[100]

With the CHADS2 scoring system anticoagulation is generally not recommended for patients with atrial fibrillation who are at low risk for thromboembolism (CHADS2 score of 0; about 20% of patients with atrial fibrillation, who face an average stroke risk of 1% per year), but it is favoured for patients at high risk (CHADS2 score ≥2; about 45% of patients with atrial fibrillation, whose stroke risk averages 4% to 5% per year) who can tolerate warfarin. For those at moderate risk (CHADS2 score of 1; about 35% of patients with atrial fibrillation, with an average stroke risk of 2% per year), either warfarin or aspirin is recommended.[96] With the new ESC 2012 guidelines update, using Chadsvasc score for stroke risk calculation, much more patients have to take anticoagulants. The reason is that broad risk categories were included (woman, age above 65, age above 75 double points, vascular disease) and that the cut-of risk value for treatment was lower than in the CHADS2 score. For instance in CHA2DS2VASC al 75 aged people and al woman above 65 with atrial fibrillation are at high risk for ischaemic stroke. With CHA2DS2VASC the overall numbers recategorised as high risk for anticoagulant drugs in atrial fibrillation have risen from 18% to 79% of all atrial fibrillation patients in general practice.[101] Moreover the ESC 2012 guidelines update advises us to anti-coagulate at CHA2DS2VASC risk score 1 at annual risk of 1,3% and only not to anti-coagulate in "really low risk" patients (approximately 5% of atrial fibrillation patients at annual risk of 0.5%).[10]

According Des Spence, general practitioner in Glasgow, the background incidence of vascular disease is in decline. In 2006 death from stroke was a quarter of what it was in 1968. The risk assessment data used to decide the benefits of anticoagulation are decades old. The decline in stroke means that we potentially overestimate stroke risk from AF by as much as 100% in today’s population. In turn this halves the absolute benefit from anticoagulation. We are on the cusp of a massive expansion of anticoagulation with the promotion of allegedly safer, newer anticoagulants, but this medication is easy to start and yet impossible to stop. If the anticoagulation numbers are wrong then we risk the slow growing of a perfect storm of over-treatment, iatrogenic harm, and bad medicine.[102]

Approval

On March 18, 2008, the European Medicines Agency granted marketing authorisation for Pradaxa for the prevention of thromboembolic disease following hip or knee replacement surgery.[103] It was approved for use in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the EU in August 2011.[104]

Pradax received a Notice of Compliance (NOC) from Health Canada on June 10, 2008,[105] for the prevention of blood clots in patients who have undergone total hip or total knee replacement surgery. Approval for atrial fibrillation patients at risk of stroke came in October 2010.[106][107]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Pradaxa on October 19, 2010, for prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.[57][108][109][110] The approval came after an advisory committee recommended the drug for approval on September 20, 2010,[111] although caution is still urged by reviewers.[112]

Uptake

An analysis of NHS primary care prescribing data for the past three years in England shows that the total number of NHS prescriptions for warfarin rose from 9,4 million in 2011 to 10.2 million prescriptions dispensed in 2012. The total prescriptions for dabigatran, including those prescribed in patients with atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism, went up from around 3,200 in 2011, to 48,300 in 2012. Prescriptions for rivaroxaban and apixaban also rose, but their use remains much lower than that of dabigatran.[113]

In the US among atrial fibrillation visits, warfarin use decreased from 55.8% visits (2010Q4) to 44.4% (2011Q4), whereas dabigatran use increased from 4.0% to 16.9%. Of atrial fibrillation visits, the fraction not treated with any oral anticoagulants has remained unchanged at ≈ 40%.[114]

In the pan-European PREFER in AF registry (recruiting from January 2012 to January 2013) 66% of patients were taking vitamin K antagonists and 6% one of the new oral anticoagulants. About 11% of patients were taking anti-platelets, and 6.5% were not receiving any treatment at all. 10% were receiving both a vitamin K antagonist anticoagulant and an anti-platelet drug, 96% of which were judged inappropriate, not being given because of recent stenting or acute coronary syndrome event. So in this cohort only 10% took combined anticoagulant anti-platelets therapy, and only 0,5% needed them, against initially 30 to 40% in the NOAC trials about dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban. 1,3% of the PREFER cohort received triple combined therapy, of wich 67% did not have an appropriate indication.[63]

Cost

The costs of new anticoagulants ($3000/year) are substantially higher than those of warfarin ($48/year), even after addition of the extra cost of INR testing and provider visits for warfarin dose adjustment.[115] This is 60 times higher. In the fourt quarter of 2011 costs of dabigatran exceeded costs of warfarin in the US: US$ 166 million (€ 129 million) against US$ 144 million (€112 million) for warfarin.[114]

Cost effectiveness

The cost effectiveness of Dabigatran is extreme variable with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERSs) from € 7468 per quality-adjusted life year QALY in Canada to € 49 030 in UK, depending from input in modelling. In countries with high-quality anticoagulation clinics ICERs are likely to be higher. Whether new oral anticoagulants with such ICERs are affordable outside high-income countries is debatable.[93] All those studies are based on the RE-LY (open label) trial data.

A Canadian study, sponsored by the manufacturer of dabigatran and based on RE-LY patient level data, assessed its cost effectiveness according to the same age adjusted dosing schedule as approved in Europe. Dabigatran was cost effective compared with warfarin, at $C10 440 (£6466; €7468; $10 026) per quality-adjusted life year QALY gained.[116]

In another UK study , dabigatran was unlikely to be cost effective in clinics, such as those in the UK, able to achieve good control of the international normalised ratio (INR) with warfarin. Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, and an age-adjusted dosing regimen, should be cost effective only for patients at increased risk of stroke or for whom INR is likely to be less well controlled. High-dose dabigatran had an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £23 082 (€26 700; $35 800) per QALY gained versus warfarin, and was more cost effective in patients with a baseline CHADS2 score of 3 or above. However, at centres that achieved good control of INRs, such as those in the UK, dabigatran 150 mg was not cost effective, at £42 386 (€49 030) per QALY gained. Differences between the Canadian and UK studies related largely to costs, which were proportionally much greater for the management of events and long-term care in the Canadian analysis. In the UK analysis, the cost of stroke was about five times higher than the cost of drugs, whereas in the Canadian study it was more than 15 times higher.[39] On the contrary, the Nice Committee (UK) concluded the most plausible incremental cost-effectiveness ratio ICERs for the whole population eligible for dabigatran were at £18 900 per QALY gained, considering average time in therapeutic range in UK was 67.9%. This was considered within the range of a cost-effective use of NHS resources, being less than £20 000 (€23 134) per QALY gained.[117]

In a study from US in a hypothetical cohort of 70-year-old patients with AF using a cost-effectiveness threshold of $50 000/quality-adjusted life-year (€39 750) for patients with the lowest stroke rate (CHADS2 stroke score of 0), only aspirin was cost-effective. For patients with a moderate stroke rate (CHADS2 score of 1 or 2), warfarin was cost-effective unless the risk of hemorrhage was high or quality of INR control was poor (time in the therapeutic range <57.1%). For patients with a high stroke risk (CHADS(2) stroke score ≥3), dabigatran 150 mg (twice daily) was cost effective unless INR control was excellent (time in the therapeutic range >72.6%). Neither dabigatran 110 mg nor dual therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) was cost effective. An additional QALY derived from using dabigatran rather than warfarin would cost $86,000 [118] In another US study in patients aged 65 years or older with nonvalvular AF at increased risk for stroke (CHADS₂ score ≥1 or equivalent) dabigatran could be a cost-effective alternative to warfarin depending on pricing in the United States. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios compared with warfarin were $51 229 per QALY for low-dose dabigatran and $45 372 per QALY for high-dose dabigatran.[119]

Anticoagulant market and marketing

An analysis from Frost and Sullivan's "Analysis of the Anticoagulant Market research" found the market of anticoagulants earned revenues of $4.7 billion in 2010 and expects it to reach $11.8 billion in 2016.[120] EvaluatePharma's new World Preview report predicts that the market for anticoagulant drugs will soar by 11.5% annually through 2018, hitting $15.3 billion in sales. Overall anticoagulant sales were $8 billion in 2012.[121]

In Australia Patient Familiarisation programs to become familiar with the product were launched to specialists and extensively to general practitioners with free treatment for 10 patients, and without warning of the increased risks of myocardial infarction and gastrointestinal bleeding in the marketing summary.[83] Boehringer Ingelheim launched a web campaign and website called “vote against stroke”, which encouraged people to write to their member of parliament to protest the delay in approving dabigatran. This was heavily criticised by the media and public, forcing the company to shut down the website.[122] The company organised almost 300 “educational events” around the country for GPs, cardiologists and other health professionals, mostly with dinner and drinks laid on, at upmarket restaurants. It spent almost $800,000 on these events, according to the company’s public declarations to Medicines Australia all between April 2011 and September 2012.[123]

In 2013, the company will extend Pradaxa-focussed educational events on stroke prevention to more than 4,000 cardiologists in China, the world’s biggest market, with support from the American College of Cardiology and in collaboration with the Chinese Society of Cardiology.[123][124]

Pharmacovigilance

On August 12, 2011, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan required Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd. to include a new boxed warning and to revise precautions of the package insert, because several fatal cases resulting from severe haemorrhagic adverse effects, including gastrointestinal haemorrhages, had been reported in patients treated with Prazaxa.[125]

On December 7, 2011, the U.S. FDA initiated an investigation into serious bleeding events associated with dabigatran, stating, "[the] FDA is working to determine whether the reports of bleeding in patients taking Pradaxa are occurring more commonly than would be expected, based on observations in the large clinical trial that supported the approval of Pradaxa [RE-LY trial]." In November 2011, Boehringer Ingelheim confirmed 260 fatal bleeding events worldwide between March 2008 and October 2011 of which 21 in Europe.[126]

The Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia published a Safety Advisory on 3 November 2011 regarding the risk of bleeding in people using dabigatran. The analysis of these reports shows some of the bleeding adverse events occurred during the transition from warfarin to dabigatran; many of the adverse events are occurring in patients on the reduced dosage regimen; and the most common site of serious bleeding for dabigatran is the gastrointestinal tract, whereas for warfarin it is intracranial. Risk factors for bleeding are: age ≥ 75 years, moderate renal impairment (30-50 ml/min) - severe renal impairment is a contraindication, concomitant use of aspirin (approximately twice the risk), clopidogrel (approximately twice the risk), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs including COX-2 inhibitors[127] (50% more risk).[128]

On 25 May 2012, the European Medicines Agency's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP)(Europe) found the frequency of occurrence of fatal bleedings with Pradaxa seen in postmarketing data was significantly lower than what was observed in the clinical trials that supported the authorisation of the medicine, but considered this issue should nonetheless be kept under close surveillance.[129]

A 2012 Medco Health Solutions report found the actual stroke and bleeding rates found at four months for dabigatran were equivalent to or higher than the stroke and bleeding rates per year for warfarin from the RE-LY trial, partly by early discontinuing dabigatran. They conclude patients need to be monitored closely to prevent bleeds or blood clots.[130]

Until recently, the most often cited cause for drug-related mortality by the FDA was warfarin.[131] In October 2006, the FDA issued a black box warning for warfarin due to its hazards. According to data compiled by QuarterWatch, in 2011, the FDA received more safety reports about dabigatran than any other drug. Dabigatran was the subject of 3,781 serious adverse events reported to the FDA in 2011, including 542 patient deaths, 2,367 hemorrhages, 291 acute renal failures and 644 strokes. Warfarin was the subject of 1,106 serious adverse events, including 72 deaths. Quarter Watch and other groups have raised concerns or made recommendations for adjusting dosage to age or renal function.[9] According to Dr. Robert Temple, FDA spokesman, few doctors notify the agency about incidents from warfarin because its risks are already well known. There were 33 million US prescriptions filled for warfarin for atrial fibrillation and other uses in 2011, and some 2.2 million prescriptions for Pradaxa according to IMS Health[132] The unexpectedly large number of reports of hemorrhage in patients receiving dabigatran could reflect differences between the clinical trial setting and the community setting, including differences in monitoring and perhaps heightened reporting and differences in patient populations.[133]

On Dec. 19, 2012, the FDA began requiring a contraindication (a warning against use) of Pradaxa (dabigatran) in patients with mechanical heart valves (also called mechanical prosthetic heart valves).The RE-ALIGN clinical trial in Europe was recently stopped because Pradaxa users were more likely to experience strokes, heart attacks, and blood clots forming on the mechanical heart valves than were users of the anticoagulant warfarin. There was also more bleeding after valve surgery in the Pradaxa users than in warfarin users.[50]

In April 2013 the FDA Office Director Ellis F. Unger wrote a “Perspective” article in the New England Journal of Medicine, discounting the post-marketing reports. The authors believed that the large number of reported cases of bleeding associated with dabigatran provided a salient example of stimulated reporting. However, the FDA Pilot Mini-Sentinel database study captured only 25 intracranial and gastrointestinal bleeding events during 14,5 months in dabigatran patients with atrial fibrillation, and the results were not adjusted for confounders.[134][135] The study explores new onset Dabigatran bleeding events compared to new onset warfarin in atrial fibrillation. It doesn't explore bleeding events from peri-operative thromboprofylaxe, switching from warfarin to dabigatran (approximately 50% of new dabigatran users) and off-label uses of dabigatran. The reliability of the Mini-Sentinel Program is unknown, but observational studies are inherent problematic owing to several sources of bias. A meta-analysis of 4 trials with dabigatran compared the results of this program regarding the gastrointestinal (GI) tract bleeding risk of dabigatran vs warfarin with the results of randomized clinical trials (RCTs). In this meta-analysis dabigatran significantly increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, compared with warfarin. Risk was 41% increased in the meta-analysis of trials, whilst in the mini-sentinel program there was a 54% decreased risk.[136] End 2013 the FDA proposes a new protocol for assessment of dabigatran and selected safety outcomes, using data from the same Mini-Sentinel Distributed Database, although "preliminary data suggest that ambulatory INR test results will be incomplete... which will limit power for assessing outcomes".[137]

History

Ximelagatran, from AstraZeneca, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was the first member of this class that could be taken orally. It was also the first oral Direct Thrombin Inhibitor within this class to show potential for treatment of Atrial Fibrillation, and the first in the United States for which FDA approval was applied. In 2006, it was withdrawn after reports of hepatotoxicity (liver damage) during trials. Also the rate of serious coronary events was higher in one trial THRIVE.[138] In an earlier study, ESTEEM, administration of ximelagatran in combination with aspirin helped to prevent a recurrence of myocardial infarction, despite a double risk of major bleedings against placebo.[139] In a post hoc analysis of the Sportif trials for atrial fibrillation, about 10% of patients took aspirin combined with warfarin or ximelegatran. The combination of aspirin plus warfarin was associated with a significantly increased annual risk for major bleeding, 3.9% versus 2.3% (P=0.01), whereas the combination of ximelegatran plus aspirin had no such effect on bleeding risk, 2.0% versus 1.9%.[70] The results of the SPORTIF 3[140][141] and 5[142] trials for atrial fibrillation were not considered to fulfil the current US FDA requirements to prove non-inferiority in efficacy. So ximelagatran was inferior to warfarin in this indication. These findings, in combination with evidence of liver toxicity and higher risk of coronary events, prevented the registration at the first application in the USA in 2004.[143] There was a big difference in outcome between open-label and double blinded trials. In the unsuccessfully double blinded SPORTIF 5 trial ( North American multicenter) the relative risk of stroke for dabigatran was numerically 24% higher than for warfarin, but in the earlier open label trial SPORTIF 3 (International multicenter) the relative risk of stroke was numerically 33% lower. In SPORTIF 5 (18,5% aspirin use) risk of cardial events was numerically lower, in SPORTIF 3 (10,5% aspirin use) risk was numerically higher [144] The SPORTIF 3 trial was the predecessor of the RE-LY , the ROCKET-AF, the ARISTOTLE and ENGAGE AF-TIMI trials for the new oral anticoagulants and their design was influenced by it. In those big trials 30 to 40% of patients were exposed initially to combined treatment of aspirin with anticoagulants, possibly resulting in doubling of incidence of major bleeding events and an increase of >2% a year in the 3 arms of the RE-LY trial,[23] and possibly similar increases in ROCKET-AF and ARISTOTLE. Also those trials proceded with international multicenter trials including centers with worse warfarin controle, advancing the benefits of NOACS. Contrary to the SPORTIF trials in later NOAC trials patiënts with previous coronary disease were not specifically included; this reversed the ratio of previous stroke to previous coronary disease at entry. This ratio was 18,5% against 41,5% in the unsuccessful SPORTIF 5 trial and inverse in the NOAC trials.[141] Reversing this ratio and adding aspirin was meant for diminishing risk of heart infarction.

Related drugs

AZD 0837 from AstraZeneca, another oral thrombine inhibitor, is under development. Due to a limitation identified in long-term stability of the extended-release AZD0837 drug product, a follow-up study from ASSURE on stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation was prematurely closed in 2010 after 2 years. There was also a numerically higher mortality against warfarin.[145][146][147] In a Phase 2 trial for AF the mean serum creatinine concentration increased by about 10% from baseline in patients treated with AZD0837, which returned to baseline after cessation of therapy.[148]

A new series of oral, direct-acting inhibitors of Factor Xa have entered clinical development, and are competitors of dabigatran. These include rivaroxaban (Xarelto) from Bayer, apixaban (Eliquis) from Bristol-Myers Squibb, betrixaban (LY517717) from Portola Pharmaceuticals, darexaban (YM150) from Astellas and edoxaban (Lixiana) (DU-176b) from Daiichi.[108] And more recent TAK-442 (Takeda) and eribaxaban (PD0348292) (Pfizer). The developpement of darexaban was discontinued in september 2011: in a trial for prevention of recurrences of myocardial infarction in top of dual antiplatelet therapy, the drug didn't work and the risk for bleeding was increased bij 300%.[149]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Pradaxa Full Prescribing Information". Boehringer Ingelheim. Retrieved October 2010.

- ↑ Hanley JP (November 2004). "Warfarin reversal". J. Clin. Pathol. 57 (11): 1132–9. doi:10.1136/jcp.2003.008904. PMC 1770479. PMID 15509671.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, Meijers JC, Buller HR, Levi M (October 2011). "Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects". Circulation 124 (14): 1573–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029017. PMID 21900088.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, Liesenfeld KH, Wienen W, Feuring M, Clemens A (June 2010). "Dabigatran etexilate--a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity". Thromb. Haemost. 103 (6): 1116–27. doi:10.1160/TH09-11-0758. PMID 20352166.

- ↑ "Pradaxa Official FDA information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, Ezekowitz MD, Jackman WM, January CT, Lowe JE, Page RL, Slotwiner DJ, Stevenson WG, Tracy CM, Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Kay GN, Le Heuzey JY, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann LS, Jacobs AK, Anderson JL, Albert N, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Guyton RA, Halperin JL, Hochman JS, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW (March 2011). "2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on Dabigatran): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines". Circulation 123 (10): 1144–50. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820f14c0. PMID 21321155.

- ↑ Aguilar M, Hart R (2005). "Antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD001925. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001925.pub2. PMID 16235290.

- ↑ "Dabigatran and atrial fibrillation: the alternative to warfarin for selected patients". Prescrire Int 21 (124): 33–6. February 2012. PMID 22413715.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Adam SS, McDuffie JR, Ortel TL, Williams JW (December 2012). "Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review". Ann. Intern. Med. 157 (11): 796–807. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00532. PMID 22928173.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P (November 2012). "2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association". Eur. Heart J. 33 (21): 2719–47. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. PMID 22922413.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 "Pradaxa". European Medicines Agency. April 9, 2012.

- ↑ Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: prevention of recurrences Prescrire 1 May 2013 http://english.prescrire.org/En/81/168/48506/0/NewsDetails.aspx

- ↑ Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Apr 14;(4):CD005981 Direct thrombin inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists or low molecular weight heparins for prevention of venous thromboembolism following total hip or knee replacement. Salazar CA, Malaga G, Malasquez G.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20393944cochrane database

- ↑ Adam SS, McDuffie JR, Lachiewicz PF, Ortel TL, Williams JW (August 2013). "Comparative effectiveness of new oral anticoagulants and standard thromboprophylaxis in patients having total hip or knee replacement: a systematic review". Ann. Intern. Med. 159 (4): 275–84. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-4-201308200-00008. PMID 24026260.

- ↑ Relative Effects of Two Different Enoxaparin Regimens as Comparators Against Newer Oral Anticoagulants: Meta-analysis and Adjusted Indirect Comparison Chun Shing Kwok, MBBS; Shiva Pradhan, MBBS; Jessica Ka-yan Yeong, MBBS; Yoon K. Loke, MD Chest. 2013;144(2):593-600 doi:10.1378/chest.12-263

- ↑ Mahendra P (2012). "Dabigatran increasingly being used off-label". Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes.

- ↑ Oldgren J, Wallentin L, Alexander JH, James S, Jönelid B, Steg G, Sundström J (June 2013). "New oral anticoagulants in addition to single or dual antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Eur. Heart J. 34 (22): 1670–80. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht049. PMC 3675388. PMID 23470494.

- ↑ Komócsi A, Vorobcsuk A, Kehl D, Aradi D (November 2012). "Use of new-generation oral anticoagulant agents in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Arch. Intern. Med. 172 (20): 1537–45. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4026. PMID 23007264.

- ↑ Agnelli G, Becattini C, Franco L (June 2013). "New oral anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism". Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 26 (2): 151–61. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2013.07.005. PMID 23953903.

- ↑ Hauel NH, Nar H, Priepke H, Ries U, Stassen JM, Wienen W (April 2002). "Structure-based design of novel potent nonpeptide thrombin inhibitors". J. Med. Chem. 45 (9): 1757–66. doi:10.1021/jm0109513. PMID 11960487. Lay summary – Montreal Gazette (October 28, 2010).

- ↑ http://www.medilexicon.com/drugs/pradaxa.php

- ↑ Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW (April 2011). "Dabigatran etexilate: a new oral thrombin inhibitor". Circulation 123 (13): 1436–50. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.004424. PMID 21464059.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 "Dabigatran for atrial fibrillation: Why we can not rely on RE-LY Therapeutics Letter Issue 80 / January - March 2011". Ti.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Reilly PA, Wallentin L (November 2010). "Newly identified events in the RE-LY trial". N. Engl. J. Med. 363 (19): 1875–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1007378. PMID 21047252.

- ↑ "Pradaxa Official FDA information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Holster IL, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET (2013). "[New oral anticoagulants increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding - a systematic review and meta-analysis]". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd (in Dutch; Flemish) 157 (44): A6500. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.041. PMID 24168849.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz M, Healey JS, Oldgren J, Yang S, Alings M, Kaatz S, Hohnloser SH, Diener HC, Franzosi MG, Huber K, Reilly P, Varrone J, Yusuf S (May 2011). "Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin in older and younger patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial". Circulation 123 (21): 2363–72. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.004747. PMID 21576658.

- ↑ "Dabigatran: life-threatening bleeding". Prescrire Int 22 (135): 41–3. February 2013. PMID 23444501.

- ↑ "Dabigatran (Pradaxa▼): risk of serious haemorrhage – contraindications clarified and reminder to monitor renal function". Mhra.gov.uk. July 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Dans AL, Connolly SJ, Wallentin L, Yang S, Nakamya J, Brueckmann M, Ezekowitz M, Oldgren J, Eikelboom JW, Reilly PA, Yusuf S (February 2013). "Concomitant use of anti-platelet therapy with dabigatran or warfarin in the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial". Circulation 127 (5): 634–40. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.115386. PMID 23271794.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Product Information as approved by the CHMP on 24 May 2012, pending endorsement by the European Commission ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS Pradaxa: Product information as approved by the CHMP on 24 May 2012, pending endorsement by the European Commission". Ema.europa.eu. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Blommel ML, Blommel AL (August 2011). "Dabigatran etexilate: A novel oral direct thrombin inhibitor". Am J Health Syst Pharm 68 (16): 1506–19. doi:10.2146/ajhp100348. PMID 21817082.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Bussey HI, Nutescu EA, Bussey M (February 2012). "Dabigatran Demystified What Warfarin Patients Should Know About this New Anticoagulant".

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Bleeding with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban. No antidote, and little clinical experience". Prescrire Int 22 (139): 155–9. June 2013. PMID 23866358.

- ↑ Uchino K, Hernandez AV (March 2012). "Dabigatran association with higher risk of acute coronary events: meta-analysis of non-inferiority randomized controlled trials". Arch. Intern. Med. 172 (5): 397–402. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1666. PMID 22231617.

- ↑ Benjo AM, Nascimento F, Macedo FYB, Javed F, Cornielle V, Pineda A, Santana O (2012). "Dabigatran consistently increases the risk of acute coronary disease: a randomized- controlled trials meta-analysis Quality of Care and Outcomes Assessment". J Am Coll Cardiol. 59 (13s1): E1871–E1871. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(12)61872-5.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Artang R, Rome E, Vidaillet H (2012). "Dabigatran and myocardial infarction, Drug or class effect. Meta-analysis of randomised trials with oral direct thrombin inhibitors". J Am Coll Cardiol 59 (13s1): E571–E571. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(12)60572-5.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Artang R, Rome E, Nielsen JD, Vidaillet HJ (September 2013). "Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials on Risk of Myocardial Infarction from the Use of Oral Direct Thrombin Inhibitors". Am. J. Cardiol. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.08.027. PMID 24075284.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Pink J, Lane S, Pirmohamed M, Hughes DA (2011). "Dabigatran etexilate versus warfarin in management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in UK context: quantitative benefit-harm and economic analyses". BMJ 343: d6333. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6333. PMC 3204867. PMID 22042753.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Pradaxa Summary of Product Characteristics". European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "Dabigatran for atrial fibrillation: Why we can not rely on RE-LY" (PDF). Therapeutics Initiative (80). 2011.

- ↑ "Pradaxa" (PDF). Summary of Product Characteristics. European Medicines Agency. p. 148.

- ↑ Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. "Pradaxa". Medications Guide. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ↑ BMJ Open 2013 Dabigatran use in Danish atrial fibrillation patients in 2011: a nationwide study Rikke Sørensen, Gunnar Gislason, Christian Torp-Pedersen, Jonas Bjerring Olesen, Emil L Fosbøl, Morten W Hvidtfeldt, Deniz Karasoy, Morten Lamberts, Mette Charlot, Lars Køber, Peter Weeke, Gregory Y H Lip, Morten Lock Hansenhttp:doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002758

- ↑ Myocardial ischemic events in ‘real world’ patients with atrial fibrillation treated with dabigatran or warfarin: A nationwide cohort study Torben Bjerregaard Larsen, Lars Hvilsted Rasmussen, Anders Gorst-Rasmussen, Flemming Skjøth, Mary Rosenzweig, Deirdre A. Lane, Gregory Y.H. Lip The American Journal of Medicine doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.12.005

- ↑ FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety review of post-market reports of serious bleeding events with the anticoagulant Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate mesylate) FDA Dabigatran Safety

- ↑ Pradaxa Gets Boxed Warning pradaxa-gets-boxed-warning

- ↑ Adherence, Persistence, and Switching Patterns of Dabigatran Etexilate - Kimberly Tsai, PharmD; Sara C. Erickson, PharmD; Jianing Yang, MS; Ann S. M. Harada, PhD, MPH; Brian K. Solow, MD; and Heidi C. Lew, PharmD - Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(9):e325--e332 Adherence-Persistence-and-Switching-Patterns-of-Dabigatran-Etexilate

- ↑ "Product Information as approved by the CHMP on 24 May 2012, pending endorsement by the European Commission. ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS". Ema.europa.eu. Retrieved 2012-101-27.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate mesylate) should not be used in patients with mechanical prosthetic heart valves". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ↑ Luis SA, Poon K, Luis C, Shukla A, Bett N, Hamilton-Craig C (May 2013). "Massive left atrial thrombus in a patient with rheumatic mitral stenosis and atrial fibrillation while anti coagulated with dabigatran". Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 6 (3): 491–2. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000253. PMID 23696587.

- ↑ "Pradaxa". Ema.europa.eu. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Tang A-W, Greer IA (June 2013). "A systematic review on the use of new anticoagulants in pregnancy". Obstetric Medicine 6 (2): 64–71. doi:10.1177/1753495X12472642.

- ↑ Chongnarungsin D, Ratanapo S, Srivali N, Ungprasert P, Suksaranjit P, Ahmed S, Cheungpasitporn W (2012). "In-Depth Review of Stroke Prevention in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation". American Medical Journal 3 (2): 100–3. doi:10.3844/amjsp.2012.100.103.

- ↑ "Pradaxa : EPAR - Product Information last updated 04/09/2012". Ema.europa.eu. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "Medication Guide. Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate)". US Food and Drug Administration. November 2011. Retrieved 2011-12-19. "Store PRADAXA at room temperature between 59°F to [sic] 86°F (15°C to 30°C). After opening the bottle, use PRADAXA within 4 months. Safely throw away any unused PRADAXA after 4 months."

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L (September 2009). "Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (12): 1139–51. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. PMID 19717844.

- ↑ Wallentin L, Yusuf S, Ezekowitz MD, Alings M, Flather M, Franzosi MG, Pais P, Dans A, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Yang S, Connolly SJ (September 2010). "Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin at different levels of international normalised ratio control for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the RE-LY trial". Lancet 376 (9745): 975–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61194-4. PMID 20801496.

- ↑ Wieloch M, Själander A, Frykman V, Rosenqvist M, Eriksson N, Svensson PJ: Anticoagulation control in Sweden: reports of time in therapeutic range, major bleeding, and thrombo-embolic complications from the national quality registry AuriculA. Eur Heart J 2011, 32: 2282 – 2289 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr134. Epub 2011 May 26

- ↑ "Breakthrough therapy dabigatran provides consistent benefit across all atrial fibrillation types and stroke risk groups" (Press release). Boehringer Ingelheim. April 4, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ↑ Turpie AG, Gent M, Laupacis A, Latour Y, Gunstensen J, Basile F, Klimek M, Hirsh J (August 1993). "A comparison of aspirin with placebo in patients treated with warfarin after heart-valve replacement". N. Engl. J. Med. 329 (8): 524–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199308193290802. PMID 8336751.

- ↑ Lane DA, Raichand S, Moore D, Connock M, Fry-Smith A, Fitzmaurice DA (July 2013). "Combined anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review". Health Technol Assess 17 (30): 1–188. doi:10.3310/hta17300. PMID 23880057.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2013. Abstracts 1075 and 1077.PREFER in AF: Stroke Prevention Therapy in AF Suboptimal

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials". Arch. Intern. Med. 154 (13): 1449–57. July 1994. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420130036007. PMID 8018000.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Apixaban, dabigatran et rivaroxaban en cas de fibrillation auriculaire : méta-analyse favorable ?". Minerva (in French) 11 (7): 84–5. 2012.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 DiNicolantonio JJ (June 2012). "Dabigatran or warfarin for the prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation? A closer look at the RE-LY trial". Expert Opin Pharmacother 13 (8): 1101–11. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.671809. PMID 22435606.

- ↑ Navgren M, Forsblad J, Wieloch M (November 2013). "Bleeding complications related to warfarin treatment: a descriptive register study from the anticoagulation clinic at Helsingborg Hospital". J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. doi:10.1007/s11239-013-1011-z. PMID 24242025.

- ↑ Wieloch M, Själander A, Frykman V, Rosenqvist M, Eriksson N, Svensson PJ (September 2011). "Anticoagulation control in Sweden: reports of time in therapeutic range, major bleeding, and thrombo-embolic complications from the national quality registry AuriculA". Eur. Heart J. 32 (18): 2282–9. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr134. PMID 21616951.

- ↑ Optimal Level of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Arterial Thrombosis in Patients With Mechanical Heart Valve Prostheses, Atrial Fibrillation, or Myocardial InfarctionA Prospective Study of 4202 Patients Marieke Torn, MD; Suzanne C. Cannegieter, MD; Ward L. E. M. Bollen, MD; Felix J. M. van der Meer, MD; Ernst E. van der Wall, MD; Frits R. Rosendaal, MD, PhD Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(13):1203-1209 doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.176

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Flaker GC, Gruber M, Connolly SJ, Goldman S, Chaparro S, Vahanian A, Halinen MO, Horrow J, Halperin JL (November 2006). "Risks and benefits of combining aspirin with anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: an exploratory analysis of stroke prevention using an oral thrombin inhibitor in atrial fibrillation (SPORTIF) trials". Am. Heart J. 152 (5): 967–73. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.024. PMID 17070169.

- ↑ Mant J, Hobbs FD, Fletcher K, Roalfe A, Fitzmaurice D, Lip GY, Murray E (August 2007). "Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial". Lancet 370 (9586): 493–503. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61233-1. PMID 17693178.

- ↑ Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart R, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, Chrolavicius S, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, Yusuf S (June 2006). "Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial". Lancet 367 (9526): 1903–12. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68845-4. PMID 16765759.