Cyclone Taylor

| Cyclone Taylor | |

|---|---|

| Hockey Hall of Fame, 1947 | |

| |

| Born | June 23, 1884 Tara, ON, CAN |

| Died | June 9, 1979 (aged 94) Vancouver, BC, CAN |

| Height | 5 ft 8.5 in (1.74 m) |

| Weight | 165 lb (75 kg; 11 st 11 lb) |

| Position | Rover |

| Shot | Left |

| Played for | Vancouver Maroons (PCHA) Vancouver Millionaires (PCHA) Renfrew Creamery Kings (NHA) Ottawa Hockey Club (ECAHA) Portage Lakes Hockey Club (IHL) |

| Playing career | 1905–1923 |

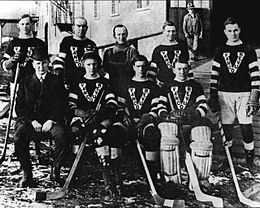

Frederick Wellington "Cyclone" Taylor, OBE, (June 23, 1884 – June 9, 1979) was a Canadian professional ice hockey player and civil servant. Taylor was one of the earliest professional players. He played professionally for the Portage Lakes Hockey Club, the Ottawa Hockey Club and the Vancouver Millionaires (later named the Maroons) from 1905 to 1923. Acknowledged as one of the first stars of hockey, Taylor was one of the most prolific scorers of his era. He won several scoring championships, and won the Stanley Cup twice, once in 1909 with Ottawa and again in 1915 with Vancouver. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1947. While in Ottawa in 1907, Taylor gained employment with the Canadian government. He maintained this employment after his career in hockey, later becoming Commissioner of Immigration for British Columbia and the Yukon.

Early life

Frederick Wellington was born in Tara, Ontario, the second son and fourth of five children to Archie and Mary Taylor. Archie, the son of Scottish immigrants, was a traveling salesman who sold farm equipment. Mary, a devout Methodist, stayed at home and raised the children.[1] At the age of six, Taylor moved with his family to Listowel, a town fifty miles south of Tara.[2] In Listowel he played for the junior and intermediate teams in the Ontario Hockey Association. In the 1904–05 season, he joined a team in Thessalon, Ontario led by Grindy Forrester when a dispute broke out as to which team held his OHA rights. The OHA, led by secretary W. A. Hewitt, refused to grant Taylor a change of residence permit and banned him from playing in the OHA. He applied for reinstatement, but was denied, and remained in Thessalon through the winter. According to some sources,[3] Hewitt wanted Taylor to play for the Toronto Marlboros and blocked his attempts to play for other teams.

Hockey career

For the 1905–06 season, Taylor played a handful of games for Portage la Prairie in Manitoba. Several teams in the new International Professional Hockey League tried to get Taylor to join them, including Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Calumet, Michigan, which even got Taylor to sign a contract. But in February 1906 he ended up reuniting with Forrester on the Portage Lake team, based in Houghton, Michigan. The team won the league championship with Taylor playing point. He had started as a forward, but was too fast for his linemates to keep up with him. Player salaries outpaced revenue in the league and the IPHL went out of business in 1907.

"In Portage La Prairie they called him a tornado, in Houghton, Michigan, he was known as a whirlwind. From now on he'll be known as Cyclone Taylor"

Taylor then joined the Ottawa Hockey Club of the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association, for whom he played two seasons, for an annual salary and the promise of a civil service job. While playing for Ottawa in 1907, the Governor General gave him the nickname "Cyclone", based on his skating ability.[5] In December 1907, it was reported that Taylor had been offered $1,500 to leave Ottawa and play for the team in Renfrew, Ontario for the 1907–08 season. He declined the offer.

Taylor played lacrosse in 1908 for the Ottawa Capitals. On June 27, 1908, he was arrested during a game for punching referee Tom Carlind in the face after receiving a penalty. The referee would not press charges, but the league president was in attendance and recommended that Taylor be given a lifetime suspension from the National Lacrosse Union. The league governors only issued a censure. The team expected Taylor to join them the following season, but he chose to focus on his job and hockey. He tried to return to the Capitals in 1910, but was released by the team. He played for the Caps in 1911.

At the start of the 1908–09 season, Taylor was given a month's vacation from his government job in Ottawa and went to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to play in the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League. The WPHL season opened in mid-November, so Taylor could play there for a month and not miss any of Ottawa's ECAHA games.

In December 1909, coming off a Stanley Cup winning season in Ottawa, it was reported that Taylor had a falling out with the club over his government job and his demand for more money. The Renfrew Hockey Club of the new National Hockey Association (NHA) announced that they had signed Taylor, but a week later Taylor said that he had decided to stay in Ottawa. After another week, Taylor changed his mind and said he would join Renfrew, signing for a reported $5,250 for one season (because of the high salaries the players got, the fans called them the Renfrew Millionaires). This made him the highest paid Canadian athlete, and he made more money than the Canadian prime minister.[6]

At the same time, Lester Patrick was given a similar contract to join the Renfrew team, along with his brother, Frank Patrick. Newsy Lalonde joined the team mid-season. Despite the high-priced talent, with four future hall-of-famers in their starting seven, Renfrew finished third. It was reported at the end of February 1910 that the team would lose $17,000 during the season and was in danger of folding. The team played one more season—with significantly reduced salaries, and without the Patricks and Lalonde—and then disbanded.

It was during his playing days at Renfrew that a legend developed around Taylor. Before his first appearance in a game for Renfrew in Ottawa, Taylor claimed that he would score a goal against Ottawa while skating backwards. In the actual game, he did not score. However, in a later game in Renfrew against Ottawa, Taylor did score a back-hand goal while skating backwards and the legend was born. However, Taylor himself long disputed the legend, saying he made the comments as a joke, and his famous "backwards" goal, only involved a brief period of backward skating and the actual goal was scored just like any other.

In 1911, Taylor became the property of Sam Lichtenhein and the NHA Montreal Wanderers. Lichtenhein wanted Taylor as a drawing card in Montreal, but, in November 1911, Taylor said he would sooner retire from hockey than join the Wanderers. To the uproar of the Wanderers, he played for Ottawa against the Wanderers on January 24, 1912. Taylor's play was so poor, he was replaced after one period, with Montreal leading 2-0.[7] Ottawa came back to win the game, 10-6. The Wanderers formally protested and the game was ordered replayed. Taylor and the Ottawa team were each fined $100 by the league and Taylor was given an indefinite suspension. However, despite this, at the end of the season in March, Taylor was selected for an NHA All-Star team which played against the three PCHA teams in British Columbia.[8]

Meanwhile, the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) was formed by Taylor's former teammates, Lester and Frank Patrick. They encouraged Taylor to come west. In November 1912, it was announced that he would be paid $1,200 to join the Vancouver Millionaires. As he prepared to leave for the west coast, Taylor said he would not play in the NHA again under any circumstances. Before he left, Taylor said one of the two new Toronto teams in the NHA was owned by Lichtenhein, who was plotting to send Taylor to Toronto and prevent him from playing for Ottawa. The accusation was denied by the presidents of both Toronto teams and by Lichtenhein, who all said he had no ownership stake in either team.

In Vancouver, Taylor was moved from cover-point (defence) to centre, a position he played the rest of his career. Taylor helped lead the Millionaires to their only Stanley Cup victory in 1915. He won five scoring titles in the PCHA, including 32 goals in 18 games in 1917–18. He ended his career in 1921. However he played one final game in the 1922–23 season, appearing with Vancouver, then known as the Maroons, against Victoria on December 8, 1922.[9] Taylor was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1947.

Taylor remained involved in hockey after he stopped playing. He was president of the Pacific Coast Hockey League from 1936 to 1940. Taylor helped start the B.C. Hockey Benevolent Association in the 1950s, and served as a director until his death. He dropped the puck in the ceremonial faceoff that preceded the expansion Vancouver Canucks' first home game when the expansion team joined the National Hockey League (NHL) in 1970. Taylor was a fixture at Canucks games, sitting in the crowd with his Homberg hat.

After hockey

Taylor joined the Canadian Immigration Branch in October 1907, a job that was arranged as an inducement to get Taylor to play for the Ottawa Hockey Club.[10] When Taylor moved to Vancouver he kept his job with the branch. In 1914, Taylor was involved, as the No. 3 immigration officer in Vancouver, in the infamous Komagata Maru incident. In the incident, a steamship of 376 Hindu, Muslim and Sikh immigrants were not permitted to land and the steamship was forced to return to India.[11] Taylor later became the Commissioner of Immigration for British Columbia and the Yukon, a position he held until his retirement in 1950. In 1949, Taylor was named as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for outstanding service to the country and community as an immigration officer in two wars.[12]

Taylor ran unsuccessfully for election, as a member of the B.C. Progressive Conservative party, in the Vancouver Centre riding in the 1952 British Columbia general election, where he finished fourth of six candidates.[13] He again ran in the Vancouver Centre riding in the 1953 British Columbia general election, where he had 1,007 votes for 5.27% of the ballots, and again finished fourth of six candidates.[14] He was elected to one term as a member of the Vancouver Parks Board.[15]

His retirement years featured some painful moments with the death of his mother in 1934, and not being able to make it to her funeral, the death of his wife — whom he had married in 1914 — from a heart seizure in 1963 and the death of his youngest child, Joan Franklin, in 1976 due to a heart weakness brought on by stringent dieting in her days as a figure skater.[16] Taylor is also reported to have been a Freemason.[17]

After breaking his hip in 1978, his health deteriorated and he died in his sleep in Vancouver on June 9, 1979 — two weeks short of his 95th birthday. In pre-game ceremonies prior to the first game of the 1979–80 season, he was honoured by the Canucks and the team's award for most valuable player was renamed the Cyclone Taylor Trophy.

Legacy

There is a chain of popular hockey equipment stores in Greater Vancouver named "Cyclone Taylor Sports", which were started by Taylor's oldest son, Fred Taylor Jr., in 1957. His second son, John Taylor, was a lawyer in Vancouver who was involved in immigration law cases until his retirement in 1988. A grandson, Mark Taylor, played in the NHL with the Philadelphia Flyers, Pittsburgh Penguins and Washington Capitals, from 1981 to 1986.

A hockey arena in Vancouver is named after Taylor.[18] In his birthplace of Tara, Ontario, the arena is named in his honor. Furthermore, in Ottawa, a street surrounding the Ottawa Senators arena, Canadian Tire Centre is named after Taylor.

The Jr. B hockey team in Listowel, Ontario is named after Taylor.

Career statistics

| Regular season | Playoffs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Team | League | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | ||

| 1902–03 | Listowel Hockey Club | OHA Jr. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1903–04 | Listowel Hockey Club | OHA | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | | — | |||

| 1905–06 | Portage la Prairie | MHA | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1905–06 | Portage Lakes Hockey Club | IHL | 6 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1906–07 | Portage Lakes Hockey Club | IHL | 23 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1907–08 | Ottawa Hockey Club | ECAHA | 10 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 40 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1908–09 | Pittsburgh PAC | WPHL | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1908–09 | Ottawa Hockey Club | ECAHA | 11 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 28 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1909–10 | Renfrew Creamery Kings | NHA | 13 | 9 | 4 | 13 | 24 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1910–11 | Renfrew Creamery Kings | NHA | 16 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 21 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1911–12 | Ottawa Hockey Club | NHA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1912–13 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 14 | 10 | 8 | 18 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1913–14 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 16 | 24 | 15 | 39 | 18 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1914–15 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 16 | 23 | 22 | 45 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 3 | ||

| 1915–16 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 18 | 22 | 13 | 35 | 9 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1916–17 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 12 | 14 | 15 | 29 | 12 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1917–18 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 18 | 32 | 11 | 43 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 15 | ||

| 1918–19 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 20 | 23 | 13 | 36 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1919–20 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 10 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1920–21 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 6 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1922–23 | Vancouver Maroons | PCHA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| NHA totals | 29 | 21 | 4 | 25 | 25 | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| PCHA totals | 131 | 159 | 104 | 263 | 59 | 16 | 17 | 6 | 23 | 18 | ||||

See also

- List of members of Canada's Sports Hall of Fame

- List of members of the Hockey Hall of Fame

- List of members of the International Hockey Hall of Fame

References

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, p. 11

- ↑ "Pioneer executive W.A. Hewitt," Peter Wilton, Total Hockey (1998 edition), Total Sports, 1998, p. 30.

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, p. 70

- ↑ Cyclone Taylor Sports (2007). "About CycloneTaylor.com". Cyclone Taylor Sports. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Beddoes, Fischler & Gitler 1969, p. 189

- ↑ "Ottawa Beat Wanderers". The Globe. 1912-01-25. p. 12.

- ↑ "Western All-Stars Win", The Globe, 1912-04-04: 14

- ↑ Coleman 1964, p. 423

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, pp. 57–63.

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, p. 163.

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, p. 193.

- ↑ Elections BC 1988, p. 238

- ↑ Elections BC 1988, p. 252

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, p. 194

- ↑ Whitehead 1977, pp. 185, 199 and 201

- ↑ "Famous Freemasons". Retrieved 2008-04-26.

- ↑ "Cyclone Taylor Arena & Play Palace". Retrieved 2010-03-29.

Bibliography

- Beddoes, Richard; Fischler, Stan; Gitler, Ira (1969), Hockey! The Story of the World's Fastest Sport, New York: The Macmillan Company, ISBN 0-02-508270-1

- Coleman, Charles L. (1964), The Trail of the Stanley Cup, Volume 1: 1893–1926 inc., Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing, ISBN 0-8403-2941-5

- Elections BC (1988), Electoral History of British Columbia, 1871–1986, Victoria, BC: Queen's Printer for British Columbia, ISBN 0-7718-8677-2

- McKinley, Michael (2000), Putting a Roof on Winter: Hockey's Rise from Sport to Spectacle, Vancouver: Greystone Books, ISBN 1-55054-798-4

- Whitehead, Eric (1977), Cyclone Taylor: A Hockey Legend, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0-385-13063-5

External links

- Cyclone Taylor's career statistics at The Internet Hockey Database

- Cyclone Taylor's biography at Legends of Hockey

- Cyclone Taylor Sports