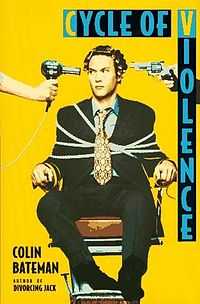

Cycle of Violence

| Cycle of Violence | |

|---|---|

First edition | |

| Author | Colin Bateman |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Crime, Dark comedy |

| Publisher | HarperCollins |

Publication date | 13 November 1995 |

| Media type | Print (Softcover) |

| Pages | 260 |

| ISBN | 9780006479352 |

| OCLC | 51194050 |

| Followed by |

Empire State (1997) |

Cycle of Violence, also known as Crossmaheart, is the first stand-alone novel by Northern Irish author, Colin Bateman, released on 13 November 1995 through HarperCollins. The novel follows a journalist named Miller and his appointment in the hostile town of Crossmaheart; it was well received by reviewers. A movie adaptation has been made, named Crossmaheart also, and was featured in a number of film festivals.

Plot

The mononymous Miller works for a Belfast newspaper named the Post, riding his bicycle nicknamed the "Cycle of Violence" from case to case. Shortly after the death of his father, he offends his boss Frank Galvin, duty editor, in a drunken outburst that leaves him curled up in the foetal position in the middle of his office. As a punishment, he is sent to the fictional town of Crossmaheart, home of the Posts sister paper, the Chronicle, as one of their reporters, Jamie Milburn, has gone missing. Miller arrives in the town and gets sexually involved with Marie Young, girlfriend of the missing Milburn. Marie suffered a sexual assault as a child and Miller, in an effort to help Marie deal with her persisting trauma, seeks out her attackers. Shortly after Miller speaks with each of the three parties; Reverend Michael Rainey, IRA member Tyrone Blair, and Tom Callaghan who is now blind and the only one of the three to show any remorse; they are each killed. Miller, now with a reputation as the "Angel of Death", attempts to solve the disappearance of Milburn while avoiding the police chasing him for these murders.

Characters

- Miller; twenty-eight-year-old journalist working for a newspaper named the Post.

- Jamie Milburn; reporter stationed in Crossmaheart who Miller is sent to replace. Boyfriend of Marie.

- Marie Young; twenty-five-year-old girlfriend of Jamie who works in a pub named "Rileys" and is Miller's love interest. Marie was raped as a child by Rainey, Callaghan and Blair.

- Michael Rainey; sexually assaulted Marie Young as a teenager, now a reverend.

- Tyrone Blair; sexually assaulted Marie Young as a teenager, now known as Curly Bap Blair and an IRA member.

- Tom Callaghan; sexually assaulted Marie Young as a teenager.

- Mrs. Hardy; owner of the guest house in which Marie Young lives.

- Tom O'Hanlon; insurance salesman and resident of Mrs. Hardy's guest house.

- Mr. & Mrs. McCauley; unemployed residents of Mrs. Hardy's guest house.

- Mrs. Brady; retired headmistress and resident of Mrs. Hardy's guest house.

- Pearse Riley; owner of "Rileys", boss of Marie and father of Johnny.

- Johnny Riley; works with Marie at "Rileys", son of Pearse.

- Martin O'Hagan; editor of the Crossmaheart Chronicle.

- Helen Sloan; reporter working for the Chronicle.

- Anne Maguire; reporter working for the Chronicle.

- Davie Morrow; IRA member.

- Frank Galvin; duty editor of the Post in Belfast.[1]

Development

The title of the novel is intended to be a pun, referring to Miller's propensity to riding his bicycle when reporting on killings or court cases.[2] Also, the fictional town of "Crossmaheart" in based on the South Armagh village of Crossmaglen, known for the numerous incidents which occurred in the area during The Troubles;[2][3] the name being a play on words referring to the childs vow "cross my heart and hope to die".[2]

Movie

The novel formed the basis for the 1998 British film Crossmaheart, directed by Henry Herbert, 17th Earl of Pembroke.[4] The movie was shown as part of the Cannes Film Festival, the Dublin Film Festival and the Boston Irish Film Festival.[5][6][7]

Reception

In Cycle of Violence, Bateman delivers the same brand of dark comedy that made his debut novel, Divorcing Jack, a success on both sides of the Atlantic. The cycle refers to the bicycle that Miller, a wisecracking, hard-drinking newspaper reporter, is forced to use after he loses his driving license. The violence, well, the violence is everywhere.

The novel was well received, with reviewers praising Batemans encapsulation of Northern Ireland during a particularly hostile time and the humour which runs throughout the book despite this.

Jonathan Dyson, for The Independent, stated that "just as The Troubles seem finally to be ending, Colin Bateman is belatedly establishing himself as their greatest satirist"; and, of the book itself, "the resulting yarn is fast-paced, very black and very funny: Roddy Doyle meets Carl Hiaasen".[8] Publishers Weekly called the novel "another side-splittingly funny, irreverent tale of violence", the finale of which they found to be "fascinating" and "devastating". They found "Bateman's forte is that, without directly addressing Northern Ireland's military / paramilitary confrontation, the book is drenched and reeking with the pervasive violence and fear of a war-torn state." The review continues that the "horror" of the situation "is cleverly framed with the blinding sparkle of dark Northern Irish wit - humor so black that it will have readers chuckling even while it reveals the dreadful realities that laughter pretends to camouflage". In conclusion, they found that "we probably learn more about life in Northern Ireland from this brilliant, often hilarious novel than from a year of Sunday magazine specials".[9] Kevin Cullen, for The Boston Globe, found that "Colin Bateman, who actually grew up and still lives in the place so many outsiders like to write about, has snatched the genre back with a vengeance, dreaming up scenarios that rely on the gallows humor peculiar to the natives of Northern Ireland"; stating also that "Only Bateman would look at the word "manslaughter" and see "man's laughter"". Cullen found that "Bateman's Vonnegut-like sense of absurdity is universal, and very funny" comparing the novel to Joseph Hellers Catch-22 in "serving up humor and pathos in equal proportions". He praised the fact that the "dialogue captures the perverse sense of humor that many people in Northern Ireland employ as a defense mechanism", stating in conclusion that "in Colin Bateman's world, the blind see and everybody dies. The reader, meanwhile, can't help but laugh".[3]

Kirkus Reviews were less effusive in their praise, finding Cycle of Violence to be "less manic - except for its luckless heroine - than Bateman's blackly comic debut, Divorcing Jack", finding that "Bateman and his hero both pay a high price for the few sweet, funny moments they wring out of this vale of tears".[10]

References

- ↑ Bateman, Colin. Cycle of Violence. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Pierce, David (22 December 2001). "Writing the North: The Contemporary Novel in Northern Ireland". Studies in the Novel (HighBeam Research). Retrieved 8 June 2012. (subscription required)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Cullen, Kevin (18 July 1996). "Irish 'Cycle' turns on dark comedy". The Boston Globe (HighBeam Research). Retrieved 8 June 2012.(subscription required)

- ↑ TJ. "Crossmaheart Review. Movie Reviews - Film". Time Out. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ Sherriff, Richard (13 May 1998). "Colin gets set to sparkle in Cannes". The News Letter (HighBeam Research). Retrieved 8 June 2012.(subscription required)

- ↑ Campbell, Brian (5 March 1998). "Cinema: Fascinating Festival highlights". An Phoblacht. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ Sherman, Paul (24 March 2000). "Hub film festival celebrates Ireland". The Boston Herald (HighBeam Research). Retrieved 8 June 2012. (subscription required)

- ↑ Dyson, Jonathan (17 December 1995). "Books; Paperback - Arts & Entertainment". The Independent. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ "Fiction Review: Cycle of Violence by Colin Bateman / Author Arcade Publishing $21.95 (288p) ISBN 978-1-55970-349-9". Publishers Weekly. 1 April 1996. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ Bateman, Colin (1 March 1996). "Cycle of Violence by Colin Bateman | Kirkus Book Reviews". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||