Cumdach

A cumdach (IPA: [ˈkuṽdax]) or book shrine is an elaborate ornamented box or case used as a reliquary to enshrine books regarded as relics of the saints who had used them in Early Medieval Ireland. They are normally later than the book they contain, often by several centuries,[1] typically the book comes from the heroic age of Irish monasticism before 800, and the surviving cumdachs date from after 1000, although it is clear the form dates from considerably earlier. Several were then considerably reworked in the Gothic period. The usual form is a design based on a cross on the main face, with use of large gems of rock crystal or other semi-precious stones, leaving the spaces between the arms of the cross for more varied decoration. Several were carried on a chain or cord, often suspended round the neck, which by placing them next to the heart was believed to bring spiritual and perhaps medical benefits (the same was done with the St Cuthbert Gospel in a leather bag in medieval Durham). They were also used to witness contracts. Many had hereditary lay keepers from among the chiefly families who had formed links with monasteries.[2] Most surviving examples are now in the National Museum of Ireland ("NMI").

Only five early examples survive, including those of the Book of Dimma and Book of Mulling at Trinity College, Dublin, and the Cathach of St. Columba and Stowe Missal at the Royal Irish Academy (the former's cumdach is in the National Museum of Ireland). Only the cumdach for the Gospels of St Molaise survives, while the book is lost, but more often the reverse is the case. Other books such as the Book of Kells, Book of Armagh and Book of Durrow are known to have once had either cumdachs or treasure bindings, or both, but with their valuable precious metals they were a natural target for looters and thieves. The church in Ireland emphasised relics that were, or were thought to be, objects frequently used by monastic saints, rather than the body parts preferred by most of the church, although these were also kept in local versions of the house-shaped chasse form, such as the Scottish Monymusk Reliquary.[3] Another Irish speciality was the bell-shrine, encasing the hand bells used to summon the community to services or meals, and one of the earliest reliquaries enshrined the belt of an unknown saint, and was probably worn as a test of truthfulness and to cure illness. It probably dates to the 8th century and was found in a peat bog near Moylough, County Sligo.[4]

Cumdachs are to be distinguished from the metalwork treasure bindings that probably covered most grand liturgical books of the period—the theft and loss of that covering the Book of Kells (if it was not a cumdach alone) is recorded. However the designs may well have been very similar; the best surviving Insular example, the lower cover of the Lindau Gospels in the Morgan Library in New York, is also centred on a large cross, surrounded by interlace panels. Treasure bindings were metalwork assemblies tacked onto the wooden boards of a conventional bookbinding, so essentially the same technically as the faces of many cumdachs, which are also attached with tacks to a core wooden box.

The surviving examples

Several of the earliest documented examples have now been lost: the Book of Durrow's is mentioned below, and the Book of Kells lost its cumdach when it was stolen in 1006. The Book of Armagh was covered in 937, and perhaps lost its cover when it was captured in battle and ransomed by the Norman John de Courcy in 1177.[5] Several of the surviving examples have high-quality early 20th century reproductions in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which are not on display there, but have good illustrations available online, unlike the original pieces.[6]

The earliest documented example was made to house and protect the Book of Durrow at the behest of King of Ireland Flann Sinna (879–916), by which point it was at Durrow, and believed to be a relic of Colum Cille. The shrine was lost in the 17th century, but its appearance, including an inscription recording the king's patronage, is recorded in a note from 1677, now bound into the book as folio IIv, although other inscriptions are not transcribed. Once in the shrine it was probably rarely if ever removed for use as a book.[7]

The shrine known as the Domhnach Airgid ("silver church") was originally 8th century, but little is visible from before a major reworking around 1350 by the abbot of Clones. A fully three-dimensional figure of Christ crucified is at the centre of the main face, with relief plaques of saints and the Virgin and Child, and other scenes on the sides which combine principal figures in relief and others in engraving. The style is rather more sophisticated than in some 14th century reworkings, with elegant running animals on small mounts at the corners, and the goldsmith who signed it, John O Bardan, is recorded living at Drogheda; by now goldsmiths in Ireland, as elsewhere in Europe, were usually laymen (NMI, R2834, 16.7 cm high).[8]

The oldest cumdach surviving largely in its original form is that made in the early 11th century for the gospels of Saint Molaise (NMI, R4006, 14.75 cm high, 11.70 wide) with the typical construction of a wooden core to which metal plaques are nailed. The top face is mainly silvered bronze and silver-gilt and has the four symbols of the Evangelists in the spaces between a cross, with gold filigree knotwork panels.[9] There is a reproduction in New York.[10]

Probably the best-known is the cumdach for the Cathach of St. Columba, an important psalter which in fact seems to date from just after the death of Columba or Colum Cille in 597, but is still probably the earliest Irish book to survive and a very prestigious relic. It belonged to the O'Donnell dynasty and was famously carried by them as a battle standard (Cathach means "Battler") in its cumdach (NMI, R2835, 25.1 cm wide), hung round the neck. The initial work on the case was done between 1072 and 1098 at Kells, but a new main face was added in the 14th century with a large seated Christ in Majesty flanked by scenes of the Crucifixion and saints in gilt repoussé (NMI R2835, 25.1 cm wide).[11]

Another cumdach used in battle was that of the Moisach, from Clonmany, County Donegal, whose metal cord survives for carrying it, probably round the neck. Originally late 11th century, it was recovered in 1534 with repoussé silver decoration with many figures round a cross (NMI 2001:84, 25 cm wide). The manuscript inside was originally associated with St Cairneach of Dulane, County Meath, but by the Gothic period had been "absorbed into the cult of St Columba".[12]

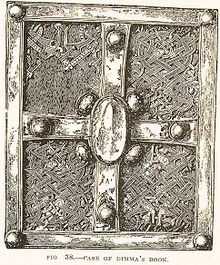

The cumdach of the Book of Dimma is from the 12th century, again with a reproduction in New York.[13] On one face it has panels of openwork decoration in Viking Ringerike style. Like the manuscript, it is in Trinity College Library, Dublin.

Stowe Missal

.png)

The Stowe Missal of about 750 retains its cumdach, with metalwork plaques attached with nails to a wooden core of oak (NMI 1883:614a, 18.7 cm high, 15.8 wide). The metalwork is elaborately decorated, with some animal and human figures, and one face and the sides probably date to between 1027 and 1033, on the basis of inscriptions recording its donation and making, while the other face is later, and can be dated to about 1375, again from its inscriptions.[14]

The older "lower" face, which is currently detached from the case, is in silver-gilt copper alloy, with a large cross inside a border that carries the inscription in Irish, which also runs along the arms of the cross. The centre of the cross was later replaced ("severely embellished" as the National Museum put it),[15] probably at the same time as the later face, by a setting for a large stone (now missing) with four lobed sections, similar to the centre of the lower face. The inscription has missing sections because of this, but can mostly be reconstructed: "It asks for a prayer for the abbot of Lorrha, Mathgamain Ua Cathail (+1037) and for Find Ua Dúngalaigh, king of Múscraige Tíre (+1033). It also mentions Donnchadh mac Briain, styled 'king of Ireland' and Mac Raith Ua Donnchada, king of the Eoganacht of Cashel (+1052) as well as the name of the maker, Donnchadh Ua Taccáin [a monk] 'of the community of Cluain (Clonmacnoise)'."[16] The four spaces between cross and border have panels of geometric openwork decoration, and there are small panels with knotwork decoration at the corners of the border and inside the curved ends of the cross members.[17]

The sides have unsilvered copper alloy plaques with figures of angels, animals, clergy and warriors, set in decorative backgrounds. The newer "upper" face, of silver-gilt, is again centred on a cross with a large oval rock crystal stone at the centre and lobed surrounds, and other gems. The inscription, engraved on plain silver plaques, runs round the border and the spaces between cross and border have four engraved figures of the crucified Christ, Virgin and Child, a bishop making a blessing gesture, and a cleric holding a book (possibly St John). The inscription "invokes a prayer for Pilib Ó Ceinnéidigh, 'king of Ormond' and his wife Áine, both of whom died in 1381. It also refers to Giolla Ruadhán Ó Macáin, abbot of the Augustinian priory of Lorrha and the maker, Domhnall Ó Tolairi".[18] Black niello is used to bring out the engraved lines of the inscription and figures, and the technique is very similar to that of the later work on the Shrine of Saint Patrick's Tooth (also in the NMI),[19] which was also given a makeover in the 1370s, for a patron some 50 km from Lorrha. They were probably added to by the same artist, something that can only rarely be seen in the few survivals of medieval goldsmith's work.[20]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to cumdachs. |

- ↑ Warner, xliv

- ↑ Antiquities, 262

- ↑ Youngs, 129–130, 134–140

- ↑ Antiquities, 183; Youngs, 58–59, 129–130

- ↑ Henry, 76

- ↑ Bought with the Rogers Fund in 1908; see individual links below.

- ↑ Meehan, 13

- ↑ Antiquities, 261–262, 270

- ↑ Antiquities, 233

- ↑ MMA reproduction, with good pictures

- ↑ Antiquities, 233, 269; Stokes, 79; Reproduction in New York

- ↑ Antiquities, 269

- ↑ New York reproduction

- ↑ Ó Floinn, "Description"; Warner, xliv – lvii, Plates I – VI; Stokes, 78; older face from Flickr

- ↑ Wallace 234

- ↑ Ó Floinn

- ↑ Wallace, 219, 234, 253; Stokes, 74

- ↑ Ó Floinn; Wallace, 271, 294

- ↑ and with a reproduction in New York

- ↑ Wallace, 262–263

See also

References

- Meehan, Bernard. The Book of Durrow: A Medieval Masterpiece at Trinity College Dublin, 1996, Town House, Dublin, ISBN 1-57098-053-5

- Ó Floinn, Raghnall, "Description" of the "Book-shrine" on The Stowe Missal, from the Royal Irish Academy, with good images and catalogue information – select "Royal Irish Academy" from drop-down "collections" menu at bottom left, then select "Stowe Missal" from the next menu.

- Stokes, Margaret, Early Christian Art in Ireland, 1887, 2004 photo-reprint, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 0-7661-8676-8, ISBN 978-0-7661-8676-7, google books

- "Antiquities": Wallace, Patrick F., O'Floinn, Raghnall eds. Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities, 2002, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, ISBN 0-7171-2829-6

- The Stowe Missal: MS. D. II. 3 in the Library of the Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, edited by George F. Warner (1906), from the Internet Archive

- Susan Youngs (ed), "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th–9th centuries AD, 1989, British Museum Press, London, ISBN 0-7141-0554-6

External links

- Report of talk, 10 October to Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland