Crimea

Autonomous Republic of Crimea

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: Процветание в единстве (Russian) Protsvetanie v yedinstve (transliteration) "Prosperity in unity" |

||||||

| Anthem: Нивы и горы твои волшебны, Родина (Russian) Nivy I gory tvoi volshebny, Rodina (transliteration) Your fields and mountains are magical, Motherland |

||||||

Location of Crimea (red) with respect to Ukraine (white).

|

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Simferopol 44°56′N 34°6′E / 44.933°N 34.100°E | |||||

| Official languages | Ukrainian | |||||

| Recognised regional languages | ||||||

| Ethnic groups (2001) |

|

|||||

| Government | Autonomous republic | |||||

| - | Viktor Plakida[2][3] | |||||

| - | Prime Minister | Anatolii Mohyliov[4] | ||||

| - | Volodymyr Konstantinov[5][6] | |||||

| Legislature | Verkhovna Rada | |||||

| Autonomy from the Russian Empire / Soviet Union | ||||||

| - | Declared | October 18, 1921 | ||||

| - | Abolished | June 30, 1945 | ||||

| - | Restoredb | February 12, 1992 | ||||

| - | Constitution | October 21, 1998 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 26,100 km2 (148th) 10,038 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2007 estimate | 1,973,185 (148th) | ||||

| - | 2001 census | 2,033,700 | ||||

| - | Density | 75.6/km2 (116th) 29.3/sq mi |

||||

| Currency | Ukrainian hryvnia (UAH) |

|||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Calling code | +380d | |||||

| Internet TLD | crimea.uac | |||||

| a. | Because Ukrainian is the only state language in Ukraine, no other language may be official, although according to the Constitution of Crimea, Russian is the language of inter-ethnic communication. However, government duties are fulfilled mainly in Russian, hence it is a de facto official language. Crimean Tatar is also used. | |||||

| b. | The Crimean Oblast's autonomy was restored when it became the Autonomous Republic of Crimea within the newly independent Ukraine. | |||||

| c. | Not officially assigned. | |||||

| d. | +380-65 for the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, 380–692 for the administratively separate City of Sevastopol. | |||||

|

||||||

Crimea (/kraɪˈmiːə/) is a peninsula of Ukraine located on the northern coast of the Black Sea with the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Ukrainian: Автономна Республіка Крим, Avtonomna Respublika Krym; Russian: Автономная Республика Крым, Avtonomnaya Respublika Krym; Crimean Tatar: Qırım Muhtar Cumhuriyeti, Къырым Мухтар Джумхуриети) occupying most of the peninsula.[7][8][9] It was often referred to with the definite article, as the Crimea, until well into the 20th century.

The territory of Crimea was conquered and controlled many times throughout its history. The Cimmerians, Greeks, Scythians, Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Khazars, the state of Kievan Rus', Byzantine Greeks, Kipchaks, Ottoman Turks, Golden Horde Tatars and the Mongols all controlled Crimea in its earlier history. In the 13th century, it was partly controlled by the Venetians and by the Genovese; they were followed by the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire in the 15th to 18th centuries, the Russian Empire in the 18th to 20th centuries, Germany during World War II and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and later the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, within the Soviet Union during the rest of the 20th century.

Crimea is now an autonomous parliamentary republic, within Ukraine,[7] which is governed by the Constitution of Crimea in accordance with the laws of Ukraine. The capital and administrative seat of the republic's government is the city of Simferopol, located in the center of the peninsula. Crimea's area is 26,200 square kilometres (10,100 sq mi) and its population was 1,973,185 as of 2007. Crimean Tatars, an ethnic minority who in 2001 made up 12.1% of the population,[10] formed in Crimea in the late Middle Ages, after the Crimean Khanate had come into existence. The Crimean Tatars were forcibly expelled to Central Asia by Joseph Stalin's government. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Crimean Tatars began to return to the region.[11] According to the 2001 Ukrainian population census 58.5% of the population of Crimea were ethnic Russians and 24.4% were ethnic Ukrainians.[12]

Etymology of the name

The name Crimea takes its origin in the name of a city of Qırım (today's Stary Krym) which served as a capital of the Crimean province of the Golden Horde. Qırım is Crimean Tatar for "my hill" (qır – hill, -ım – my).[citation needed] Russian Krym is a Russified form of Qırım. The ancient Greeks called Crimea Tauris (later Taurica, Ταυρική in Ancient Greek), after its inhabitants, the Tauri. The Greek historian Herodotus mentions that Heracles plowed that land using a huge ox ("Taurus"), hence the name of the land. Herodotus also refers to a nearby region called "cremni or 'the Cliffs'" which may also refer to the Crimean peninsula, notable for its cliffs along what is otherwise a flat northern coastline of the Black Sea.

In English, much as with Ukraine itself, Crimea is sometimes referred to with the definite article, the Crimea, as in the Netherlands, the Gambia, etc., but usage without the article has become more frequent in journalism since the years of the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

History

Early history

.jpg)

Taurica was the name of Crimea in antiquity. Taurica was inhabited by a variety of peoples. The inland regions were inhabited by Scythians and the mountainous south coast by the Taures, an offshoot of the Cimmerians. Greek settlers inhabited a number of colonies along the coast of the peninsula, notably the city of Chersonesos in modern Sevastopol. In the 2nd[citation needed] century BCE the eastern part of Taurica became part of the Bosporan Kingdom, before being incorporated into the Roman Empire in the 1st century BC. During the 1st, 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, Taurica was host to Roman legions[13] [citation needed](not legion(s), only some aids) and colonists in Charax, Crimea. Taurica was eventually renamed by the Crimean Tatars, from whose language Crimea's modern name derives. The word "Crimea" comes from the Crimean Tatar name Qırım, via Greek Krimea (Κριμαία).[citation needed]

Throughout the later centuries, Crimea was invaded or occupied successively by the Goths (AD 250), the Huns (376), the Bulgars (4th–8th century), the Khazars (8th century), the state of Kievan Rus' (10th–11th centuries), the Byzantine Empire (1016), the Kipchaks (Kumans) (1050), and the Mongols (1237). In the 13th century, the Republic of Genoa seized the settlements which their rivals, the Venetians, had built along the Crimean coast and gained control of the Crimean economy and the Black Sea commerce for two centuries.[citation needed]

A number of Turkic peoples, now collectively known as the Crimean Tatars, have been inhabiting the peninsula since the early Middle Ages. After the destruction of the Golden Horde by Timur, the Crimean Tatars founded an independent Crimean Khanate in 1441, under Hacı I Giray, a descendant of Genghis Khan. The Crimean Tatars controlled the steppes that stretched from the Kuban and to the Dniester River, however, they were initially unable to take control over commercial Genoese towns. After the capture of Genoese towns, the Ottoman Sultan held Meñli I Giray captive,[14] later releasing him in return for accepting Ottoman sovereignty above the Crimean Khans and allowing them rule as tributary princes of the Ottoman Empire.[15][16]:78 However, the Crimean Khans still had a large amount of autonomy from the Ottoman Empire. In 1774, the Crimean Khans fell under Russian influence with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca and, in 1783, the entire Crimea was annexed by the Russian Empire.[16]:176

Crimea became part of Russia's Taurida Governorate and was the site of much of the fighting in the Crimean War (1853–1856), which devastated much of the economic and social infrastructure of the peninsula.

Crimea in the 20th and 21st centuries

In the Soviet Union

During the Russian Civil War following the overthrow of the Russian Empire, Crimea changed hands a number of times and was a stronghold of the anti-Bolshevik White Army. It was in Crimea that the White Russians led by General Wrangel made their last stand against the Anarchist forces of Nestor Makhno and the Red Army in 1920. Approximately 50,000 White prisoners of war and civilians were summarily executed by shooting or hanging after the defeat of general Wrangel at the end of 1920.[17] This is considered one of the largest massacres in the Civil War.[18]

On 18 October 1921, the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created as part of the Russian SFSR which, in turn, became part of the Soviet Union.[15] Crimea experienced two severe famines in the 20th century, the Famine of 1921–1922 and the Holodomor of 1932–1933.[19]

During World War II, Crimea was the scene of some of the bloodiest battles. The Axis forces under the command of the Germans suffered heavy casualties in the summer of 1941 as they tried to advance through the narrow Isthmus of Perekop linking Crimea to the Soviet mainland. Once the Axis forces broke through, they occupied most of Crimea, with the exception of the city of Sevastopol, which held out from October 1941 until 4 July 1942 when the Germans finally captured the city. From 1 September 1942, the peninsula was administered as the Generalbezirk Krim (general district of Crimea) und Teilbezirk (and sub-district) Taurien. In spite of heavy-handed tactics by the Nazis and their allies, the Crimean mountains remained an unconquered stronghold of the native resistance until the day when the peninsula was freed from the occupying force in 1944.

On 18 May 1944, the entire population of the Crimean Tatars was forcibly deported in the "Sürgün" (Crimean Tatar for exile) to Central Asia by Joseph Stalin's Soviet government as a form of collective punishment, on the grounds that they had collaborated with the Nazi occupation forces.[16] An estimated 46% of the deportees died from hunger and disease.[citation needed] On 26 June of the same year, the Armenian, Bulgarian, and Greek population was also deported to Central Asia. By the end of summer of 1944, the ethnic cleansing of Crimea was complete. In 1967, the Crimean Tatars were rehabilitated, but they were banned from legally returning to their homeland until the last days of the Soviet Union. The Crimean ASSR was abolished on 30 June 1945 and transformed into the Crimean Oblast (province) of the Russian SFSR.

On 19 February 1954, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union issued a decree transferring the Crimean Oblast from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.[20] In post-war years, Crimea thrived as a prime tourist destination, built with new attractions and sanatoriums for tourists. Tourists came from all over the Soviet Union and neighbouring countries.[15] Crimea's infrastructure and manufacturing was also developed, particularly around the sea ports at Kerch and Sevastopol and in the oblast's landlocked capital of Simferopol.

Following a referendum held on January 20, 1991, the Crimean Oblast was upgraded to that of an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on February 12, 1991 by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR.[21]

In independent Ukraine

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Crimea became part of the newly independent Ukraine which led to tensions between Russia and Ukraine.[nb 1] With the Black Sea Fleet based on the peninsula, worries of armed skirmishes were occasionally raised. Crimean Tatars began returning from exile and resettling in Crimea.

On 26 February 1992, the Verkhovniy Sovet (the Crimean parliament) renamed the ASSR the Republic of Crimea and proclaimed self-government on 5 May 1992[22][23] (which was yet to be approved by a referendum to be held 2 August 1992[24]) and passed the first Crimean constitution the same day.[24] On 6 May 1992 the same parliament inserted a new sentence into this constitution that declared that Crimea was part of Ukraine.[24]

.jpg)

On 19 May, Crimea agreed to remain part of Ukraine and annulled its proclamation of self-government but Crimean Communists forced the Ukrainian government to expand on the already extensive autonomous status of Crimea.[16]:587 In the same period, Russian president Boris Yeltsin and Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk agreed to divide the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet between Russia and the newly formed Ukrainian Navy.[25]

On 14 October 1993, the Crimean parliament established the post of President of Crimea and agreed on a quota of Crimean Tatars represented in the Council of 14. However, political turmoil continued. Amendments to the constitution eased the conflict,[citation needed] but on 17 March 1995, the parliament of Ukraine intervened, scrapping the Crimean Constitution and removing Meshkov along with his office for his actions against the state and promoting integration with Russia.[26] After an interim constitution, the current constitution was put into effect, changing the territory's name to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Following the ratification of the May 1997 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership on friendship and division of the Black Sea Fleet, international tensions slowly eased off. However, in September 2008, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister Volodymyr Ohryzko accused Russia of giving out Russian passports to the population in the Crimea and described it as a "real problem" given Russia's declared policy of military intervention abroad to protect Russian citizens.[27]

On 24 August 2009, anti-Ukrainian demonstrations were held in Crimea by ethnic Russian residents. Sergei Tsekov (of the Russian Bloc[28] and then deputy speaker of the Crimean parliament[29]) said then that he hoped that Russia would treat the Crimea the same way as it had treated South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[30] Chaos in the Ukrainian parliament during a debate over the extension of the lease on a Russian naval base erupted on 27 April 2010 after Ukraine’s parliament ratified the treaty that extends Russia's lease on a military wharf and shore installations in the Crimean port Sevastopol until 2042. Along with Verkhovna Rada, the treaty was ratified by the Russian State Duma as well.[31]

Government and politics

Crimea is an autonomous republic within the unitary state of Ukraine with the Presidential Representative serving as a governor and replacing once established a post of president. The legislative body is a 100-seat parliament, the Supreme Council of Crimea.[32]

The executive power is represented by the Council of Ministers, headed by a Chairman who is appointed and dismissed by the Verkhovna Rada, with the consent of the President of Ukraine.[6][33] The authority and operation of the Supreme Council and the Council of Ministers of Crimea are determined by the Constitution of Ukraine and other the laws of Ukraine, as well as by regular decisions carried out by the Supreme Council of Crimea.[33]

Justice is administered by courts that belong to the judicial system of Ukraine.[33]

Elections and parties

While not an official body controlling Crimea, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People is a representative body of the Crimean Tatars, which could address grievances to the Ukrainian central government, the Crimean government, and international bodies.[34]

During the 2004 presidential elections, Crimea largely voted for the presidential candidate Viktor Yanukovych. In both the 2006 Ukrainian parliamentary elections and the 2007 Ukrainian parliamentary elections, the Yanukovych-led Party of Regions also won most of the votes from the region, as they did in the 2010 Crimean parliamentary election.[35]

Crimea – United States relations

On 18 February 2009 the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea sent a letter to the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine and the President of Ukraine in which it stated that it deemed it inexpedient to open a representative office of the United States in Crimea and it urged the Ukrainian leadership to give up this idea. The letter had passed in the Crimean parliament by a 77 to 9 roll-call vote with one abstention.[36] The letter would also be sent to the Chairman of the UN General Assembly.

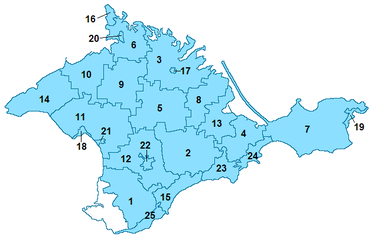

Administrative divisions

Crimea is subdivided into 25 regions: 14 raions (districts) and 11 city municipalities, officially known as "territories governed by city councils".[37] While the City of Sevastopol is located on the Crimean peninsula, it is administratively separate from the rest of Crimea and is one of two special municipalities of Ukraine. Sevastopol, while having a separate administration, is tightly integrated within the infrastructure of the whole peninsula.

Raions

|

|

City municipalities

|

|

Geography and climate

Crimea is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea and on the western coast of the Sea of Azov, bordering Kherson Oblast from the North. There are two rural communities of Henichesk Raion in Kherson Oblast that are physically located on the peninsula, on the smaller peninsula Arabat Spit, Shchaslyvtseve and Strilkove. Although located in the southwestern part of the Crimean peninsula, the city of Sevastopol has a special but separate municipality status within Ukraine. Crimea's total land area is 26,100 km2 (10,077 sq mi).

Crimea is connected to the mainland by the 5–7 kilometres (3.1–4.3 mi) wide Isthmus of Perekop. At the eastern tip is the Kerch Peninsula, which is directly opposite the Taman Peninsula on the Russian mainland. Between the Kerch and Taman peninsulas, lies the 3–13 kilometres (1.9–8.1 mi) wide Strait of Kerch, which connects the waters of the Black Sea with the Sea of Azov. The peninsula consists of many other smaller peninsulas such as Arabat Spit, Kerch peninsula, Herakles peninsula, Tarhan Qut peninsula and many others. Crimea also features other headlands such as Cape Priboiny, Cape Tarhan Qut,[citation needed] Sarych, Nicholas Cape, Cape Fonar, Cape Fiolent, Qazan Tip,[citation needed] Cape Aq Burun, and many others.

Relief

Geographically, the peninsula is generally divided into three zones: steppes, mountains and southern coast.

The southeast coast is flanked at a distance of 8–12 kilometres (5.0–7.5 mi) from the sea by a parallel range of mountains, the Crimean Mountains.[38] These mountains are backed by secondary parallel ranges. Seventy-five percent of the remaining area of Crimea consists of semiarid prairie lands, a southward continuation of the Pontic steppes, which slope gently to the northwest from the foot of the Crimean Mountains. The main range of these mountains shoots up with extraordinary abruptness from the deep floor of the Black Sea to an altitude of 600–750 metres (1,969–2,461 ft), beginning at the southwest point of the peninsula, called Cape Fiolente. It was believed that this cape was supposedly crowned with the temple of Artemis, where Iphigeneia is said to have officiated as priestess.[39] Uchan-su waterfall on the south slope of the mountains is the highest in Ukraine.

Numerous kurgans, or burial mounds, of the ancient Scythians are scattered across the Crimean steppes.

The terrain that lies beyond the sheltering Crimean Mountain range is of an altogether different character. Here, the narrow strip of coast and the slopes of the mountains are smothered with greenery. This "riviera" stretches along the southeast coast from capes Fiolente and Aya, in the south, to Feodosiya, and is studded with summer sea-bathing resorts such as Alupka, Yalta, Gurzuf, Alushta, Sudak, and Feodosiya. During the years of Soviet rule, the resorts and dachas of this coast served as the prime perquisites of the politically loyal.[citation needed]why here? and ref? In addition, vineyards and fruit orchards are located in the region. Fishing, mining, and the production of essential oils are also important. Numerous Crimean Tatar villages, mosques, monasteries, and palaces of the Russian imperial family and nobles are found here, as well as picturesque ancient Greek and medieval castles.

Hydrography

The Crimean coastline is broken by several bays and harbors. These harbors lie west of the Isthmus of Perekop by the Bay of Karkinit; on the southwest by the open Bay of Kalamita, with the ports of Yevpatoria and Sevastopol;[citation needed](not Sevastopol) on the north by the Bay of Arabat of the Isthmus[citation needed](nonsense) of Yenikale or Kerch; and on the south by the Bay of Caffa[citation needed](name?) or Feodosiya, with the port of Feodosiya. The natural borders between Crimean peninsula and the Ukrainian mainland serves the saline Lake Syvash (a unique shallow system of estuaries and bays).

Urban landscape

The two biggest cities of peninsula are Sevastopol and Simferopol, the other major centers of urban development are Kerch (heavy industry and fishing center), Dzhankoy (transportation hub), Yalta (holiday resort) and others.

Major cities

|

|

Climate

Most of Crimea has a temperate continental climate, except for the south coast where it experiences a humid[citation needed] subtropical climate, due to warm influences from the Black Sea. Summers can be hot (28 °C or 82.4 °F Jul average) and winters are cool (−0.3 °C or 31.5 °F Jan average) in the interior, on the south coast winters are milder (4 °C or 39.2 °F Jan average) and temperatures much below freezing are exceptional. Precipitation throughout Crimea is low, averaging only 400 mm (15.7 in) a year. Because of its climate, the southern Crimean coast is a popular beach and sun resort for Ukrainian and Russian tourists.

Tourism

The development of Crimea as a holiday destination began in the second half of the 19th century. The development of the transport networks brought masses of tourists from central parts of Russia. On the border of the centuries began a sensational developing of palaces, villas and dachas all saved till today. They are one of the main icons of Crimean urban characteristics and tourist destinations. There are many Crimean legends about famous touristic places, which attract attention of tourists.

A new, phase of the tourist developing began when soviet government realised the potential of the healing abilities of the local air, lakes and therapeutic muds. It became a "health" destination for all Soviet workers, hundreds of thousands of the tourists visited Crimea. Nowadays Crimea is more of a get away destination than a "health-improvement" destination. Most visited areas are: the south shore of Crimea with cities of Yalta and Alushta, the western shore - Eupatoria and Saki, the south-eastern shore - Feodosia and Sudak.

Crimea possesses significant historical and natural resources and is a region where it is possible to find practically any type of landscape; mountain ranges and plateaus, grasslands, caves. Further Saki poses unique therapeutic mud and Eupatoria has vast empty beaches with the purest quartz sand.[40]

According to National Geographic, Crimea is among the top 20 travel destinations in 2013.[41]

Places of interest

- Koktebel

- Livadia Palace

- Mount Mithridat

- Scythe's Treasure

- Swallow's Nest

- Tauric Chersonesos

- Vorontsov's Palace (Alupka)

Economy

The main branches of the Crimean economy are tourism and agriculture.[citation needed] Industrial plants are situated for the most part in the northern regions of the republic. Important industrial cities include Dzhankoy, housing a major railway connection, Krasnoperekopsk and Armyansk, among others.

The most important industries in Crimea include food production, chemical fields, mechanical engineering and metal working, and fuel production industries.[33] Sixty percent of the industry market belongs to food production. There are a total of 291 large industrial enterprises and 1002 small business enterprises.[33]

The main branches of vegetation production in the region include cereals, vegetable-growing, gardening, and wine-making, particularly in the Yalta and Massandra regions. Other agricultural forms include cattle breeding, poultry keeping, and sheep breeding.[33] Other products produced on the Crimean Peninsula include salt, porphyry, limestone, and ironstone (found around Kerch).[42]

Transport

- Public transportation

Almost every settlement in Crimea is connected with another settlement with bus lines. Crimea contains the longest (96 km or 59 mi) trolleybus route in the world, stretching from Simferopol to Yalta.[43] The trolleybus line starts in near Simferopol's Railway Station through the mountains to Alushta and on to Yalta. The length of line is about 90 km. It was founded in 1959.

Railroad lines running through Crimea include Armyansk—Kerch (with a link to Feodosiya), and Melitopol—Sevastopol (with a link to Yevpatoria), connecting Crimea to the Ukrainian mainland.

- Highways

- E105/M18 - North-Crimean Channel (bridge, starts), Dzhankoy, Simferopol, Alushta, Yalta (ends)

- E97/M17 - Perekop (starts), Armyansk, Dzhankoy, Feodosiya, Kerch (ferry, ends)

- H05 - Krasnoperekopsk, Simferopol (access to the Simferopol International Airport)

- H06 - Simferopol, Bakhchisaray, Sevastopol

- H19 - Yalta, Sevastopol

- P16

- P23 - Simferopol, Feodosiya

- P25 - Simferopol, Yevpatoria

- P27 - Sevastopol, Inkerman (completely within the city of Sevastopol)

- P29 - Alushta, Sudak, Feodosiya

- P34 - Alushta, Yalta

- P35 - Hrushivka, Sudak

- P58 - Sevastopol, Port "Komysheva Bukhta" (completely within the city of Sevastopol)

- P59 (completely within the city of Sevastopol)

- Sea transport

The cities of Yalta, Feodosiya, Kerch, Sevastopol, Chornomorske and Yevpatoria are connected to one another by sea routes. In the cities of Yevpatoria and nearby townlet Molochnoye are tram systems.

Demographics

| Part of a series on |

| Crimean Tatars |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

| History |

|

| People and groups |

As of 2005, the total population of Crimea is 1,994,300.

From 1989 to 2001, Crimea's population declined by 396,795 people, representing 16.33% of the 1989 population, despite the return of displaced groups such as Crimean Tatars. From 2001–2005 the population declined by another 39,400 people, representing a decline from 2001 of another 2%.[citation needed](Sevastopol was included in 1989)

Age structure

- 0-14 years: 14.9%

(male 150,199/female 141,649)

(male 150,199/female 141,649) - 15-64 years: 70.4%

(male 653,041/female 724,235)

(male 653,041/female 724,235) - 65 years and over: 14.7%

(male 94,047/female 193,251) (2013 official)

(male 94,047/female 193,251) (2013 official)

Median age

- total: 39.9 years

- male: 36.2 years

- female: 43.5 years

(2013 official)

(2013 official)

Ethnic groups

According to 2001 Ukrainian Census, the population of Crimea was 2,033,700.[44] The ethnic makeup was comprised the following self-reported groups: Russians: 58.32%; Ukrainians: 24.32%; Crimean Tatars: 12.1%; Belarusians: 1.44%; Tatars: 0.54%; Armenians: 0.43%; and Jews: 0.22%.[45]

| Ethnic group |

1897 census | 1939 census | 1959 census | 1979 census | 1989 census | 2001 census | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Russians | 180,963 | 33.11% | 49.6% | 71.4% | 68.4% | 67.1% | 1,180,441 | 58.32% | ||||

| Ukrainians | 64,703 | 11.84% | 13.7% | 22.3% | 25.6% | 25.8% | 492,227 | 24.32% | ||||

| Crimean Tatars | 194,294 | 35.55% | 19.4% | 0% | 0.7% | 1.6% | 243,433 | 12.03% | ||||

| Others | ||||||||||||

Other minorities are Black Sea Germans, Romani people, Bulgarians, Poles, Azerbaijanis, Koreans, Greeks and Italians. The number of Crimea Germans was 45,000 in 1941.[46] In 1944, 70,000 Greeks and 14,000 Bulgarians from the Crimea were deported to Central Asia and Siberia,[47] along with 200,000 Crimean Tatars and other nationalities.[48]

Ukrainian is the single official state language countrywide, and is the sole language of government in Ukraine. According to the census mentioned, 77% of Crimean inhabitants named Russian as their native language; 11.4% – Crimean Tatar; and 10.1% – Ukrainian.[49] In Crimea government business is carried out mainly in Russian. Attempts to expand the usage of Ukrainian in education and government affairs have been less successful in Crimea than in other areas of the nation.[50]

Currently two thirds of the migrants into Crimea are from other regions of Ukraine; every 5th migrant is from the former Soviet Union and every 40th from outside of it. Three quarters of those leaving Crimea move to other areas in Ukraine. Every 20th migrates to the West.[49]

The number of Crimean residents who consider Ukraine their motherland increased sharply from 32% to 71.3% from 2008 through 2011; according to a poll by Razumkov Center in March 2011,[51] although this is the lowest number in all Ukraine (93% on average across the country).[51] Surveys of regional identities in Ukraine have shown that around 30% of Crimean residents claim to have retained a self-identified "Soviet identity".[52]

Demographic trends

The population of the Crimean Peninsula has been consistently falling at a rate of 0.4% per year.[53] This is particularly apparent in both the Russian and Ukrainian ethnic populations, whose growth rate has been falling at the rate of 0.6% and 0.12% annually respectively. In comparison, the ethnic Crimean Tatar population has been growing at the rate of 0.9% per annum.[54]

The growing trend in the Crimean Tatar population has been explained by the continuing repatriation of Crimean Tatars mainly from Uzbekistan.

Culture

Sport

.jpg)

Crimea figures prominently in Ukrainian sports, especially the most popular: association football. The most successful Crimean football club is Tavriya Simferopol who won the inaugural Ukrainian Premier League title in 1992. FC Sevastopol also currently competes in the top division. In the Ukrainian First League, Crimea has been represented by clubs such as FC Feniks-Illichovets Kalinine, FC Krymteplitsia Molodizhne (from Simferopol suburbs) and FC Tytan Armyansk.

Crimea has a bandy federation. Their chairman is Vice president of Ukrainian Bandy and Rink-bandy Federation.[55] In 2011 they for the first time organised the rink bandy tournament Crimea Open.[56]

Famous Crimean athletes include Yana Klochkova, Galina Prozumenshchikova, Kateryna Serebrianska, Ruslana Taran and Oleksandr Usyk.

Media

Almost 100 broadcasters and around 1,200 publications are registered in Crimea, although no more than a few dozen operate or publish regularly.[7] Of them most use the Russian language only.[7] Crimea's first Tatar-owned, Tatar-language TV launched in 2006.[7]

Gallery

-

The Black Sea Fleet Museum in Sevastopol

-

Vorontsov's Palace

-

Catholic church in Yalta

See also

Further reading

- (German) Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick: Ein Spielball der Mächte: Die Krim im Schwarzmeerraum (VI.-XV. Jahrhundert). =A Pawn of the Powers- The Crimea in the Black Sea Region (VI-XV. Century). In: Stefan Albrecht, Falko Daim, Michael Herdick (Hg.): Die Höhensiedlungen im Bergland der Krim. Umwelt, Kulturaustausch und Transformation am Nordrand des Byzantinischen Reiches. RGZM, Mainz 2013, S. 25-56. ISBN 978-3-884-67220-4 (with an Englisch and Russian Summary)

- (German) Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick, Rainer Schreg: Neue Forschungen auf der Krim. Geschichte und Gesellschaft im Bergland der südwestlichen Krim - eine Zusammenfassung. =New Researches on the Crimea. Synthesis: A Hypothetical Model of Competing Neighborhoods. In: Stefan Albrecht, Falko Daim, Michael Herdick (Hg.): Die Höhensiedlungen im Bergland der Krim. Umwelt, Kulturaustausch und Transformation am Nordrand des Byzantinischen Reiches. RGZM, Mainz 2013, S. 471-497. ISBN 978-3-884-67220-4 (with an Englisch and Russian Summary)

- (Russian) Bazilevich Basil Mitrofanovich. (1914) From the History of Moscow-Crimea Relations in the First Half of the 17th Century (Из истории московско-крымских отношений в первой половине XVII века) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Bantysh-Kamensky Nikolay. (1893) Register of cases of Crimean court with 1474 to 1779 (Реестр делам крымского двора с 1474 по 1779 год) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Berg Nikolai. (1858) Sevastopol album by N. Berg (Севастопольский альбом Н. Берга) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Berezhkov Michael N.Plan for the conquest of the Crimea compiled during the reign of Emperor Alexis of Russia Slav scholar Yuri Krizhanich (План завоевания Крыма составленный в царствование государя Алексея Михайловича ученым славянином Юрием Крижаничем) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Berezhkov Michael N. (1888) Russian captives and slaves in the Crimea (Русские пленники и невольники в Крыму) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Bogdanovich Modest I. (1876) Eastern War 1853-1856 (Восточная война 1853-1856 гг.) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

- (Russian) Dubrovin Nikolai Fedorovich. (1900) History of the Crimean War and the defense of Sevastopol (История Крымской войны и обороны Севастополя) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

- (Russian) Dubrovin Nikolai Fedorovich. (1885–1889) Joining the Crimea to Russia (Присоединение Крыма к России) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

Footnotes and references

- Footnotes

- References

- ↑ (Ukrainian) Майже 60% росіян вважають, що Крим - це Росія Almost 60% of Russians believe, that Crimea - is Russian, Ukrayinska Pravda (10 September 2013)

- ↑ Presidential Representative in the Republic of Crimea

- ↑ Plakida appointed Yanukovych's envoy to Crimea, Kyiv Post (28 February 2012).

- ↑ Former Interior Minister Mohyliov heads Crimean government, Interfax Ukraine (8 November 2011).

- ↑ Vasyl Dzharty of Regions Party heads Crimean government, Kyiv Post (March 17, 2010).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Crimean parliament to decide on appointment of autonomous republic's premier on Tuesday, Interfax Ukraine (7 November 2011)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Regions and territories: The Republic of Crimea, BBC News

- ↑ Autonomous Republic of Crimea

- ↑ Government Portal of The Autonomous Republic of Crimea

- ↑ http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/nationality/Crimea/ English: {{{1}}}

- ↑ Pohl, J. Otto. The Stalinist Penal System: A Statistical History of Soviet Repression and Terror. Mc Farland & Company, Inc, Publishers. 1997. 23.

- ↑ About number and composition population of AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA by data All-Ukrainian population census', Ukrainian Census (2001)

- ↑ http://www.naukawpolsce.pap.pl/en/news/news,397105,polish-archaeologists-discovered-a-roman-garrison-commanders-house-in-the-crimea.html

- ↑ Soldier Khan

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "History". blacksea-crimea.com. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ↑ Gellately, Robert (2007). Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf. p. 72. ISBN 1-4000-4005-1.

- ↑ Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartosek, Jean-Louis Panne, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stephane Courtois, Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, hardcover, page 100, ISBN 0-674-07608-7. Chapter 4: The Red Terror

- ↑ Famine in Crimea

- ↑ "Подарунок Хрущова". Як Україна відбудувала Крим

- ↑ "Day in history - 20 January". RIA Novosti (in Russian). January 8, 2006. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ↑ Wolczuk, Kataryna (August 31, 2004). "Catching up with 'Europe'? Constitutional Debates on the Territorial-Administrative Model in Independent Ukraine". Taylor & Francis Group. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

Wydra, Doris (November 11, 2004). "The Crimea Conundrum: The Tug of War Between Russia and Ukraine on the Questions of Autonomy and Self-Determination". Retrieved March 25, 2007. - ↑ Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 1857431871 (page 540)

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Russians in the Former Soviet Republics by Pål Kolstø, Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 0253329175 (page 194)

- ↑ Ready To Cast Off, TIME Magazine, June 15, 1992

- ↑ Laws of Ukraine. Verkhovna Rada law No. 93/95-вр: On the termination of the Constitution and some laws of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Passed on 1995-03-17. (Ukrainian)

- ↑ Cheney urges divided Ukraine to unite against Russia 'threat. Associated Press. September 6, 2008.

- ↑ , ()

- ↑ , ()

- ↑ Russia and Ukraine in Intensifying Standoff

- ↑ Update: Ukraine, Russia ratify Black Sea naval lease, Kyiv Post (April 27, 2010)

- ↑ The Verkhovna Rada of Crimea should not be confused with the national Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 "Autonomous Republic of Crimea – Information card". Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ↑ Ziad, Waleed; Laryssa Chomiak (February 20, 2007). "A lesson in stifling violent extremism". CS Monitor. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ Local government elections in Ukraine: last stage in the Party of Regions’ takeover of power, Centre for Eastern Studies (October 4, 2010)

- ↑ Crimean parliament votes against opening U.S. diplomatic post, Interfax-Ukraine (18 February 2009)

- ↑ "Infobox card — Avtonomna Respublika Krym". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ↑ The Crimean Mountains may also be referred to as the Yaylâ Dağ or Alpine Meadow Mountains.

- ↑ See the article "Crimea" in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.

- ↑ "Crimea Travel Guide". CrimeaTravel. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ↑ Best Trips 2013 Crimea, National Geographic Society

- ↑ Bealby, John T. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. Cambridge University Press. p. 449.

- ↑ "The longest trolleybus line in the world!". blacksea-crimea.com. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Regions of Ukraine / Autonomous Republic of Crimea". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ↑ "Results / General results of the census / National composition of population". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ↑ "A People on the Move: Germans in Russia and in the Former Soviet Union: 1763 – 1997". North Dakota State University Libraries.

- ↑ "The Persecution of Pontic Greeks in the Soviet Union" (PDF)

- ↑ "Crimean Tatars Divide Ukraine and Russia". The Jamestown Foundation. June 24, 2009.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Results / General results of the census / Linguistic composition of the population / Autonomous Republic of Crimea". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ↑ Bondaruk, Halyna (March 3, 2007). "Yushchenko Appeals to Crimean Authority Not to Speculate on Language". Ukrayinska Pravda. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Poll: Most Crimean residents consider Ukraine their motherland, Kyiv Post (11 April 2011)

- ↑ Soviet conspiracy theories and political culture in Ukraine:Understanding Viktor Yanukovych and the Party of Region by Taras Kuzio (23 August 2011)

- ↑ Falling Population growth rate in Crimea (in Ukrainian)

- ↑ Population growth in Crimea (in Ukrainian)

- ↑ Ukrainian Bandy and Rink-bandy Federation

- ↑ Ukrainian national and regional competition

- Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- "Autonomous Republic of Crimea – Information card". Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press - Crimea, terra di mille etnie, 1993 di Giuseppe D'Amato in Il Diario del Cambiamento. Urss 1990 – Russia 1993. Greco&Greco editori, Milano, 1998. pp. 247–252. ISBN 88-7980-187-2 (The Diary of the Change. USSR 1990 – Russia 1993) Book in Italian.

- Crimea, la penisola regalata di Giuseppe D'Amato in L’EuroSogno e i nuovi Muri ad Est. L’Unione europea e la dimensione orientale. Greco&Greco editori, Milano, 2008. pp. 99–107 ISBN 978-88-7980-456-1 (The EuroDream and the new Walls at East. The European Union and the Eastern dimension) Book in Italian.

External links

| Find more about Crimea at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- Official links

- (English) (Ukrainian) (Russian) (Crimean Tatar) crimea-portal.gov.ua, the official portal of the Council of Ministers of Crimea.

- (English) (Ukrainian) (Russian) (Crimean Tatar) rada.crimea.ua, the official web-site of the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea.

- (Ukrainian) (Russian) www.ppu.gov.ua, the official web-site of the Permanent Presidential Representative in the Republic of Crimea.

- History

- (English) '-5-pochti-vojna/ Series about the recent political history of Crimea by Independent Analytical Center for Geopolitical Studies “Borysfen Intel”

- Historical footage of Crimea, 1918, filmportal.de

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)