Counter-recruitment

Counter-recruitment is a strategy often taken up to oppose war. Counter-recruitment is an attempt to prevent military recruiters from enlisting civilians into the military. There are several methods commonly utilized in a counter-recruitment campaign, ranging from the political speech to direct action. Such a campaign can also target entities connected to the military, such as intelligence agencies, or private corporations, especially those with defense contracts.

In the United States

Counter-recruitment (which has long been a strategy of pacifist and other anti-war groups) received a boost in the United States with the somewhat unpopularity of the war in Iraq and brief recruitment difficulties of branches of the U.S. military, particularly the Army; although the Army has met, or exceeded, its recruitment goals year after year during that period.. Beginning in early 2005, the U.S. counter-recruitment movement grew, particularly on high school and college campuses, where it is often led by students who see themselves as targeted for military service in a war they do not support.

Early history

The counter-recruitment movement was the successor to the anti-draft movement with the end of conscription in the United States in 1973, just after the end of the Vietnam War. The military increased its recruiting efforts, with the total number of recruiters, recruiting stations, and dollars spent on recruiting each more than doubling between 1971 and 1974.[1] Anti-war and anti-draft activists responded with a number of initiatives, using tactics similar to those used by counter-recruiters today. Activists distributed leaflets to students, publicly debated recruiters, and used equal-access provisions to obtain space next to recruiters to dispute their claims. The American Friends Service Committee (A.F.S.C.) and the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors (C.C.C.O.) began publishing counter-recruitment literature and attempting to coordinate the movement nationally. These organizations have been continuously involved in counter-recruitment to the present day.[2]

High schools

Most counter-recruitment work in the U.S. is focused at the policy level of public school systems. This work is generally done by parents and grandparents of school-aged children, and the most common activity is information and advocacy with school officials (principals, school boards, etc.) and with the general population in their local school area. CR at the K12 level is categorically different from other movements, since most of the students are underaged minors and parents are their legal custodians and guardians, not the schools.

The most common policy goal is that the frequency of military recruiters' visits to public schools, their locations in schools, and their types of activities be controlled rather than unlimited. Many of the larger urban school districts have implemented such guidelines since 2001.

Other goals have included "truth in recruiting", that counselors or curriculum elements be implemented to address the deficiency in high school students' understanding of war and the military life, rather than allowing military recruiters to perform that role.

On high school campuses, counter-recruitment activists since 2001 have also focused around a provision of the No Child Left Behind Act, which requires that high schools provide contact and other information to the military for all of their students who do not opt out.

Counter-recruitment campaigns have attempted to change school policy to ban recruiters regardless of the loss of federal funds, to be active about informing students of their ability to opt out, and/or to allow counter-recruiters access to students equal to the access given to military recruiters. These political campaigns have had some success, particularly in the Los Angeles area, where one has been led by the Coalition Against Militarism in Our Schools, and the San Francisco Bay Area. A simpler and easier, though perhaps less effective, strategy by counter-recruiters has been to show up before or after the school day and provide students entering or exiting their school with opt-out forms, produced by the local school district or by a sympathetic national legal organization such as the American Civil Liberties Union or the National Lawyers Guild.

Organizations which have attempted to organize such campaigns on a national scale include A.F.S.C. and C.C.C.O., the Campus Antiwar Network (C.A.N.), and the War Resisters League. Code Pink, with the Ruckus Society, has sponsored training camps on counter-recruitment as well as producing informational literature for use by counter-recruiters. United for Peace and Justice has counter-recruitment as one of its seven issue-specific campaigns. The Mennonite Central Committee is another resource on the subject. Some of these organizations focus on counter-recruitment in a specific sector, such as high schools or colleges, the National Network Opposing the Militarization of Youth, founded in 2004, deals with the larger issue of militarism as it affects young people.

Colleges and universities

On U.S. college campuses, C.A.N. claims its protests have chased recruiters off over a dozen schools since its founding in 2003, including San Francisco State University, City College of New York, University of Illinois at Chicago, UC Santa Cruz, and (in the first and perhaps most-known protest, as president Bush was being inaugurated) Seattle Central Community College, as well as disrupting recruitment at countless others.[3] A common method against military recruitment at schools which have non-discrimination policies that protect lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students has been to demand that military recruitment be prevented in order to comply with these policies, as these schools consider the Don't ask, don't tell policy discriminatory against LGBT persons; however, with the repeal of DADT, the services are open to homosexuals.

C.A.N. also organized nationally coordinated student counter-recruitment protests on December 6, 2005, as the Supreme Court heard arguments in Rumsfeld v. FAIR to decide the legality of the Solomon Amendment, which requires universities to allow military recruiters or forfeit their federal funding.

At colleges and universities, counter-recruitment activities have resulted in discipline from university administrators, who have threatened activists with penalties including expulsion, and law enforcement, who have arrested and sometimes used physical violence against activists engaged in counter-recruitment protest. C.A.N. says that it has faced ten "major free speech cases" relating to its counter-recruitment activities. In every case, all charges against students were dropped after a public defense campaign was waged. Many counter-recruitment activities at universities also appear in the Pentagon's surveillance database of anti-war protests, a portion of which was leaked to NBC in December 2005.

Proposition I/College Not Combat

One significant result of the counter-recruitment movement was the passage, with 60% in support, of Proposition I/College Not Combat in San Francisco on November 5, 2005. This proposition, which does not carry enforcement power, declared the city's opposition to military recruitment in public high schools and universities and stated that money should instead be directed toward scholarships. It was written by Todd Chretien.

Arguments surrounding recruitment

In addition to the general debates supporting or opposing war, or particular wars, and the alleged connection of the military to homophobia, sexism, racism, militarism, and imperialism, there are debates about the recruitment process itself. These debates, listed below, do not include Recruiter Improprieties which are specifically defined in military regulations and orders, or crimes such as sexual contact with minors, since both the military as well as counter-recruiters are strongly opposed to them.

- Whether recruiters exploit a lack of other options for underprivileged young people, in a phenomenon sometimes called the Poverty Draft. Allegations have surfaced that imply a large majority of the enlisted population of the (US) military enlisted as a result of being unable to sustain employment or for lack of better options. USLAW under FOIA request, obtained the numbers of recruits by zip code, and showed significant correlation with low incomes. The DOD conducts large-scale surveys into youths' "propensity to enlist". Results available on Internet consistently show the top reasons youth enlist are money for college, job training and experience, and pay. Current recruiting CSM Stephan Frennier has denied[citation needed] the allegation of a Poverty Draft.

- Whether recruiters are honest. Various investigations, such as one in May 2005 by Cincinnati's WLWT, have revealed dishonest conduct by individuals; a recruiter interviewed in the documentary Why We Fight notes that people in his profession have "the bad reputation of used car salesmen." Military defenders argue that the bad actions of a few shouldn't taint the whole. Counter-recruiters argue that high pressure on recruiters creates systemic dishonesty. The U.S. Army shut down its entire recruitment apparatus for a single day in 2005 in order to "refocus" on ethical conduct.[4]

- Whether the military will pay for an education. Through various programs, such as the G.I. Bill in the U.S., which offers up to $71,000, young people are given an incentive to join the military in the form of scholarships for college when their enlistments expire. This is the primary reason why many enlist; a young recruit interviewed in Why We Fight, William Solomon, cites this as his motivation. Counter-recruiters argue that this is a false hope, noting for example that 57% of those who apply for G.I. Bill benefits do not receive them, and that the average net payment to those who do is less than $2200. This is a consequence of various eligibility requirements; 65% of eligible veterans receive money.[5]

- Whether military service provides job skills. Recruiters often suggest that personal and technical skills learned in the military will improve later employment prospects in civilian life, with very similar skills utilized for nursing and electronic and mechanical repair. Counter-recruiters claim that this does not apply to most recruits, citing for example a study in the U.S. which found that 12% of male and 6% of female veterans say they have used their military skills in their civilian careers.[6] However, a study titled "Military Experience & CEOs: Is There a Link?" found that "leadership skills acquired during military training can absolutely enhance one’s chances for success in corporate life."[7] Furthermore, the report cited was published in 1993 and does not account for how civilian hiring practices impact this statistic.

- Whether reform from within is a better solution than disassociation. Many who agree that there are problems in the military argue that these will be better solved if those who recognize them as problems gain influence in the military rather than avoiding it. Others argue in response that the military's problems are structural, and that its disciplinary hierarchy prevents successful internal pressure. This debate occurs mostly in narrower contexts, such as debates about whether left-wing activists should join the military or whether universities in the U.S. should have ROTC programs, rather than in discussions of general enlistment.[8]

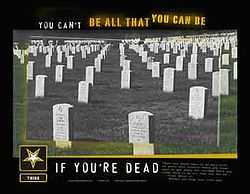

- Whether the military inaccurately promotes a "romanticized" view of combat - using catchphrases such as honor, courage, and service - and glosses over death, injury, and civilian suffering, in order to give recruits a "soft" vision of the job.[citation needed]

- Whether recruitment activities including JROTC violates the United Nations sponsored Convention on the Rights of the Child by targeting students under the age of 17.[9]

Resistance to military recruitment in Ireland

Military recruitment and resistance to it has historically been a significant political issue in colonies of the British Empire. This is true in Ireland especially as the campaigns for independence from the British Empire intensified. The British Army raised many regiments from English colonies to fight in conflicts such as the Crimean War, World War I, and World War II. Irish songs opposing recruitment to the British army that date from the mid-19th century provide some evidence that this colonial policy was resisted - examples include Arthur McBride, Mrs. McGrath, and Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye. However this cultural resistance is itself indicative of just how widespread military recruitment actually was in Ireland at the time. Many Irish people continued to be recruited in Ireland to fight in colonial regiments until World War I. The Irish Home Rule Movement decided to support English military recruitment in Ireland in the hope that by acting as loyal subjects of the empire the empire would feel indebted to Ireland and grant it independence. As the Irish independence movement shifted from parliamentary to extra parliamentary channels after the 1916 Rising, and moving towards the Irish War of Independence, there was a shift away from the earlier strategic support for recruitment to the British Army. The Irish War of Independence targeted police stations and this led to the replacement of colonial law enforced by the Royal Irish Constabulary with martial law enforced by the British Army. In this context, joining the British Army was no longer joining an army to fight wars overseas but joining an organisation that was actually fighting a war in Ireland. A cultural understanding of joining the British Army as a kind of collaboration with an oppressive Empire then developed. This opposition to military recruitment was more motivated by nationalism than pacifism or opposition to militarism per se and often coincided with support for Irish para-military organisations such as the Irish Volunteers and Irish Republican Brotherhood. After the Irish War of Independence the British Army no longer operated in the Southern Republic of Ireland and Irish people continued to join the British Army for economic reasons as they had done when Ireland was still part of the British Empire though now they had to first travel to England in order to do so. The continued presence of the British Army in Northern Ireland meant, especially during the height of "the troubles" between the 1970s and 1990s, meant that military recruitment to the British Army was still a highly political issue. Depending on your point of view, there was either widespread popular resistance to the British Military in Northern Ireland or the Irish Republican Army violently enforced non-cooperation with all aspects of the British government in the nationalist communities they controlled.

There has been little or no opposition in Ireland to recruitment for the official Irish army known as the Irish Defence Forces which are often described primarily as peacekeepers despite their participation in dubious UN interventions in recently liberated former colonies such as the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville) in the 1960s.

Counter-recruitment in Canada

In response to the Canadian Forces' role as a member of the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, an anti-war movement developed in Canada which has tried to utilize counter-recruitment as a part of its efforts. In particular, Operation Objection emerged as the umbrella counter-recruitment campaign in Canada.[10] Operation Objection claimed to have active counter-recruitment operations in 8 to 10 Canadian cities.[11] However, coordinated attempts at counter-recruitment activism in Canada have been fairly limited as of late, and for the most part, unsuccessful.

In the 2005-06 academic year at York University, the York Federation of Students, a federation representing ten of the university's student unions, clashed with a Canadian Forces recruiter forcibly removing the recruiter and the kiosk from the Student Center. York University maintains that the Canadian Forces have the same right to recruit as any other employer participating in career fairs on campus.[12]

On October 25, 2007, an attempt by the student union at the University of Victoria to ban Canadian Forces from participating in career fairs on campus failed when the student body voted overwhelmingly in favor of allowing the Canadian military to participate in recruitment and career development activities available to students. Approximately 500 students, five times the usual attendance, appeared at the Annual General Meeting of the University of Victoria Students' Society (UVSS), and voted to defeat the motion proposed to stop the Canadian Forces from appearing on campus at career development events, with an estimated 25 votes in favor of the ban. Those voting against the ban argued that the ban was a restriction on freedom of choice and an infringement of students' free speech, that it went beyond the mandate of student government, and that student union executives should not be advocating policy that does not reflect the views of the fee-paying student body.[13][14][15][16]

In November 2007, the Minister of Education for Prince Edward Island, Gerard Greenan, was requested by the Council of Canadians to ban military recruitment on PEI campuses. The Minister responded that military service "is a career and... we think its right to let the Armed Forces have a chance to present this option to students."[17]

Notes

- ↑ Cortright, David (2005). Soldiers in Revolt. Haymarket Books. p. 187. ISBN 1-931859-27-2.

- ↑ Cortright, David (2005). Soldiers in Revolt. Haymarket Books. p. 237. ISBN 1-931859-27-2.

- ↑ "Past Actions and Events". Retrieved 2006-03-18.

- ↑ "Amid Scandal, Recruitment Halts". CBS News. 2005-05-20.

- ↑ Diener, Sam; Munro, Jamie (June–July 2005). "Military Money for College: A Reality Check". Peacework (AFSC).

- ↑ "Honesty in Recruitment Newsletter" (PDF). Coalition Against Militarism in our Schools. Retrieved 2006-03-18.

- ↑ "Yes, sir! Military officers do well as CEOs". MSNBC. 2006-06-16.

- ↑ Wilkes, Sean (2004). "Advocates for Columbia ROTC and Students United for America Brief: Proposal to Return ROTC to Columbia’s Campus". Retrieved 2006-03-18.

- ↑ "Soldiers of Misfortune". ACLU. 2008.

- ↑ http://www.dnd.ca/site/newsroom/view_news_e.asp?id=1703

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Carson Jerema (2007-10-29). "Students say let the military recruit". Macleans.ca. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ↑ Colonist, Times (2007-10-26). "UVic students overturn military recruitment ban". Canada.com. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ↑ "Canadian Forces Ban Vote at the UVSS AGM". YouTube. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ↑

- ↑ "Recruit away in P.E.I. schools". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||