Cosmochlaina

| Cosmochlaina Temporal range: Late Silurian to Early Devonian | |

|---|---|

| |

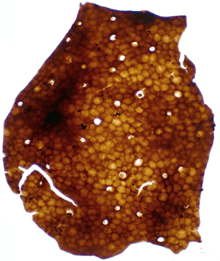

| Cuticle of Cosmochlaina, retrieved from the Burgsvik beds by acid maceration. Cells about 12 μm in diameter. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae (?) |

| Phylum: | Nematophyta |

| Class: | †Nematophytina |

| Order: | †Nematophytales |

| Family: | †Nematothalaceae Strother 1993 |

| Genus: | Cosmochlaina Edwards 1986 |

| Species | |

| |

The form genus was put forwards by Dianne Edwards, and is diagnosed by inwards-pointing flanges and randomly oriented pseudo-cellular units.[3] Projections on the outer surface are always present, and sometimes also appear on the inner surface; however, the surface of the cuticle itself is always smooth.[3] The holes in the cuticle are often covered by round flaps, loosely attached along a side.[3]

Where Nematothallus was sometimes used to relate only to tube-like structures, Cosmochlaina was used in reference to the cuticle fragments. Material discovered later revealed its internal anatomy, which comprises a lichen-like mat of 'hyphae'.Edwards, Dianne; Axe, Lindsey; Honegger, Rosmarie (2013). "Contributions to the diversity in cryptogamic covers in the mid-Palaeozoic:Nematothallusrevisited". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society: n/a. doi:10.1111/boj.12119.

It has been suggested that the pores of Cosmochlaina represent broken-off rhizoids, on the basis that rotting and acid treatment of extant liverworts produces a similar perforated texture.[4] However, the status of this form genus in any one kingdom is not secure; members could, for example, represent arthropod cuticle.[5] Alternatively, different species may in fact represent different parts of the same organism.[3] Based on the more recent material, a lichen affinity seems most plausible.[6]

See also

- Nematothallus, a closely related sister taxon

- Evolutionary history of plants

References

- ↑ Kenrick, P.; Crane, P.R. (1997). "The origin and early evolution of plants on land". Nature 389 (6646): 33–39. Bibcode:1997Natur.389...33K. doi:10.1038/37918.

- ↑ Gensel, P.G.; Johnson, N.G.; Strother, P.K. (1990). "Early Land Plant Debris (Hooker's" Waifs and Strays"?)". PALAIOS 5 (6): 520–547. doi:10.2307/3514860. JSTOR 3514860.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Edwards, D. (1986). "Dispersed cuticles of putative non-vascular plants from the Lower Devonian of Britain". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 93 (3): 259–275. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1982.tb01025.x.

- ↑ Graham, L.E.; Wilcox, L.W.; Cook, M.E.; Gensel, P.G. (2004). "Resistant tissues of modern marchantioid liverworts resemble enigmatic Early Paleozoic microfossils". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101 (30): 11025–11029. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111025G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400484101. PMC 503736. PMID 15263095.

- ↑ Taylor, T.N. (1988). "The Origin of Land Plants: Some Answers, More Questions". Taxon 37 (4): 805–833. doi:10.2307/1222087. JSTOR 1222087.

- ↑ Edwards, Dianne; Axe, Lindsey; Honegger, Rosmarie (2013). "Contributions to the diversity in cryptogamic covers in the mid-Palaeozoic:Nematothallusrevisited". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society: n/a. doi:10.1111/boj.12119.

| ||||||||||||||||