Congruence subgroup

In mathematics, a congruence subgroup of a matrix group with integer entries is a subgroup defined by congruence conditions on the entries. A very simple example would be invertible 2x2 integer matrices of determinant 1, such that the off-diagonal entries are even.

An important class of congruence subgroups is given by reduction of the ring of entries: in general given a group such as the special linear group SL(n, Z) we can reduce the entries to modular arithmetic in Z/NZ for any N >1, which gives a homomorphism

- SL(n, Z) → SL(n, Z/N·Z)

of groups. The kernel of this reduction map is an example of a congruence subgroup – the condition is that the diagonal entries are congruent to 1 mod N, and the off-diagonal entries be congruent to 0 mod N (divisible by N), and is known as a principal congruence subgroup, Γ(N). Formally a congruence subgroup is one that contains Γ(N) for some N,[1] and the least such N is the level or Stufe of the subgroup.

In the case n=2 we are talking then about a subgroup of the modular group (up to the quotient by {I,-I} taking us to the corresponding projective group): the kernel of reduction is called Γ(N) and plays a big role in the theory of modular forms. Further, we may take the inverse image of any subgroup (not just {e}) and get a congruence subgroup: the subgroups Γ0(N) important in modular form theory are defined in this way, from the subgroup of mod N 2x2 matrices with 1 on the diagonal and 0 below it.

More generally, the notion of congruence subgroup can be defined for arithmetic subgroups of algebraic groups; that is, those for which we have a notion of 'integral structure' respected by the subgroup, and so some general idea of what 'congruence' means.

Congruence subgroups and topological groups

Are all subgroups of finite index actually congruence subgroups? This is not in general true, and non-congruence subgroups exist. It is however an interesting question to understand when these examples are possible. This problem about the classical groups was resolved by Bass, Milnor & Serre (1967). .

It can be posed in topological terms: if Γ is some arithmetic group, there is a topology on Γ for which a base of neighbourhoods of {e} is the set of subgroups of finite index; and there is another topology defined in the same way using only congruence subgroups. We can ask whether those are the same topologies; equivalently, if they give rise to the same completions. The subgroups of finite index give rise to the completion of Γ as a pro-finite group. If there are essentially fewer congruence subgroups, the corresponding completion of Γ can be bigger (intuitively, there are fewer conditions for a Cauchy sequence to comply with). Therefore the problem can be posed as a relationship of two compact topological groups, with the question reduced to calculation of a possible kernel. The solution by Hyman Bass, Jean-Pierre Serre and John Milnor involved an aspect of algebraic number theory linked to K-theory.

The use of adele methods for automorphic representations (for example in the Langlands program) implicitly uses that kind of completion with respect to a congruence subgroup topology - for the reason that then all congruence subgroups can then be treated within a single group representation. This approach - using a group G(A) and its single quotient G(A)/G(Q) rather than looking at many G/Γ as a whole system - is now normal in abstract treatments.

Congruence subgroups of the modular group

Detailed information about the congruence subgroups of the modular group Γ has proved basic in much research, in number theory, and in other areas such as monstrous moonshine.

Modular group Γ(r)

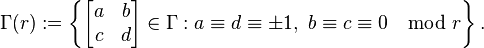

For a given positive integer r, the modular group Γ(r) is defined as follows:[2]

Modular group Γ1(r)

For a given positive integer r, the modular group Γ1(r) is defined as follows:[2]

Modular group Γ0(r)

For a given positive integer r, the modular group Γ0(r) is defined as follows:[2]

It can be shown that for a prime number p, the set

(where Sτ = −1/τ and Tτ = τ + 1) is a fundamental region of Γ0(r).

The normalizer Γ0(p)+ of Γ0(p) in SL(2,R) has been investigated; one result from the 1970s, due to Jean-Pierre Serre, Andrew Ogg and John G. Thompson is that the corresponding modular curve (the Riemann surface resulting from taking the quotient of the hyperbolic plane by Γ0(p)+) has genus zero (the modular curve is an elliptic curve) if and only if p is 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 41, 47, 59 or 71. When Ogg later heard about the monster group, he noticed that these were precisely the prime factors of the size of M, he wrote up a paper offering a bottle of Jack Daniel's whiskey to anyone who could explain this fact – this was a starting point for the theory of Monstrous moonshine, which explains deep connections between modular function theory and the monster group.

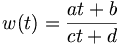

Modular group Λ

The modular group Λ (also called the theta subgroup) is another subgroup of the modular group Γ. It can be characterized as the set of linear Möbius transformations w that satisfy

with a and d being odd and b and c being even. That is, it is the congruence subgroup that is the kernel of reduction modulo 2, otherwise known as Γ(2).

References

- Bass, H.; Milnor, John Willard; Serre, Jean-Pierre (1967), "Solution of the congruence subgroup problem for SLn (n≥3) and Sp2n (n≥2)", Publications Mathématiques de l'IHÉS (33): 59–137, ISSN 1618-1913, MR 0244257 (Erratum)

- Lang, Serge (1976). Introduction to Modular Forms. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften 222. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-07833-9.