Congruence of squares

In number theory, a congruence of squares is a congruence commonly used in integer factorization algorithms.

Derivation

Given a positive integer n, Fermat's factorization method relies on finding numbers x, y satisfying the equality

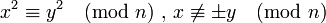

We can then factor n = x2 - y2 = (x + y)(x - y). This algorithm is slow in practice because we need to search many such numbers, and only a few satisfy the strict equation. However, n may also be factored if we can satisfy the weaker congruence of squares condition:

.

.

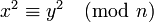

From here we easily deduce

This means that n divides the product (x + y) (x - y), but since we also require x ≠ ±y (mod n), n divides neither (x+y) nor (x−y) alone. Thus (x + y) and (x − y) each contain proper factors of n. Computing the greatest common divisors of (x + y,n) and of (x - y,n) will give us these factors; this can be done quickly using the Euclidean algorithm.

Congruences of squares are extremely useful in integer factorization algorithms and are extensively used in, for example, the quadratic sieve, general number field sieve, continued fraction factorization, and Dixon's factorization. Conversely, because finding square roots modulo a composite number turns out to be probabilistic polynomial-time equivalent to factoring that number, any integer factorization algorithm can be used efficiently to identify a congruence of squares.

Further generalizations

It is also possible to use factor bases to help find congruences of squares more quickly. Instead of looking for  from the outset, we find many

from the outset, we find many  where the y have small prime factors, and try to multiply a few of these together to get a square on the right-hand side.

where the y have small prime factors, and try to multiply a few of these together to get a square on the right-hand side.

Examples

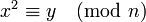

Factorize 35

We take n = 35 and find that

.

.

We thus factor as

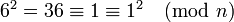

Factorize 1649

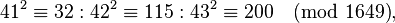

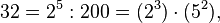

Using n = 1649, as an example of finding a congruence of squares built up from the products of non-squares (see Dixon's factorization method), first we obtain several congruences

of these, two have only small primes as factors

and a combination of these has an even power of each small prime, and is therefore a square

yielding the congruence of squares

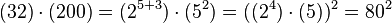

So using the values of 80 and 114 as our x and y gives factors

See also

![(\gcd[6-1,35])\cdot (\gcd[6+1,35])=(5)\cdot (7)=35.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/c/a/3/2ca373ac9ad594311311bf6b77faccd3.png)

![(\gcd[114-80,1649])\cdot (\gcd[114+80,1649])=(17)\cdot (97)=1649.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/3/c/1/7/3c172e7ccbdbd9953070b88ad9acc6f4.png)