Compressible flow

Compressible flow is the area of fluid mechanics that deals with fluids in which the fluid density varies significantly in response to a change in pressure. Compressibility effects are typically considered significant if the Mach number (the ratio of the flow velocity to the local speed of sound) of the flow exceeds 0.3, or if the fluid undergoes very large pressure changes. The most distinct differences between the compressible and incompressible flow models are that the compressible flow model allows for the existence of shock waves and choked flow.

Definition

Compressible flow describes the behaviour of fluids that experience significant variations in density. For flows in which the density does not vary significantly, the analysis of the behaviour of such flows may be simplified greatly by assuming a constant density. This is an idealization, which leads to the theory of incompressible flow. However, in the many cases dealing with gases (especially at higher velocities) and those cases dealing with liquids with large pressure changes, the significant variations in density can occur, and the flow should be analysed as a compressible flow if accurate results are to be obtained.[1]

Allowing for a change in density brings an additional variable into the analysis. This is in contrast to incompressible flows, which can usually be solved by considering only the equations from conservation of mass and conservation of momentum. Usually, the principle of conservation of energy is included. However, this introduces another variable (temperature), and so a fourth equation (such as the ideal gas equation) is required to relate the temperature to the other thermodynamic properties in order to fully describe the flow.

When defining what is meant by a compressible flow, it is useful to compare the density to a reference value, such as the stagnation density,  , which is the density of the fluid if it were to be slowed down isentropically to stationary. As a general rule of thumb, if the change in density relative to the stagnation density is greater than 5%, then the fluid should be analysed as a compressible flow. For an ideal gas with a ratio of specific heats of 1.4, this occurs at a Mach number greater than approximately 0.3. Below this value, however, whether or not a specific case should be treated as compressible or incompressible depends largely on the level of accuracy that is required.[2]

, which is the density of the fluid if it were to be slowed down isentropically to stationary. As a general rule of thumb, if the change in density relative to the stagnation density is greater than 5%, then the fluid should be analysed as a compressible flow. For an ideal gas with a ratio of specific heats of 1.4, this occurs at a Mach number greater than approximately 0.3. Below this value, however, whether or not a specific case should be treated as compressible or incompressible depends largely on the level of accuracy that is required.[2]

Compressible Flow Phenomena

Two of the most distinctive phenomena which occur in compressible flow are the possibility of choked flow(see Internal Flows) and the presence of acoustic waves, which may also be referred to as either compression or expansion waves, depending on whether they lead to an increase or decrease in pressure.[1]

Shock Waves

Shock waves are one of the most common examples of compressible flow phenomena. A shock is characterised by a discontinuous change in the thermodynamic properties. In one dimensional flows, shock waves can form when a series of compression waves coalesce, or when a membrane separating two regions of differing pressure is suddenly removed. This is the technique often used to produce shock waves in shock tubes (see Shock Tubes).

In two and three dimensional supersonic flows, oblique shock waves occur as a result of a change in direction of the flow. A classic example of these shock waves are those shock waves that form off the nose of a supersonic aircraft.

Aerodynamics

Aerodynamics is a subfield of fluid dynamics and gas dynamics, and is primarily concerned with obtaining the forces that air exerts on an object. For Mach numbers greater than about 0.3, density changes are significant, and the flow should be considered compressible for an accurate representation of reality.

Subsonic Aerodynamics

Due to the complexities of compressible flow theory, it is often easier to calculate the incompressible flow characteristics first, and then employ a correction factor to obtain the actual flow properties. Several correction factors exist with varying degrees of complexity and accuracy.

Prandtl–Glauert transformation

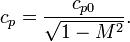

The Prandtl-Glauert transformation is found by linearizing the potential equations associated with compressible, inviscid flow. The Prandtl–Glauert transformation or Prandtl–Glauert rule (also Prandtl–Glauert–Ackeret rule) is an approximation function which allows comparison of aerodynamical processes occurring at different Mach numbers. It was discovered that the linearized pressures in such a flow were equal to those found from incompressible flow theory multiplied by a correction factor. This correction factor is given below.:[3]

where

- cp is the compressible pressure coefficient

- cp0 is the incompressible pressure coefficient

- M is the Mach number.

This correction factor is correct only for two-dimensional flow. For general three-dimensional flows, it is necessary to apply the full Prandtl-Glauert transformation to the geometry, and then apply Göthert's Rule [4] to get the physical pressure coefficient and forces.

This 2D Prandtl-Glauert Rule, or the general 3D Göthert's Rule, work well until transonic flow starts to appear, typically for Mach numbers below 0.7 for 2D airfoils.

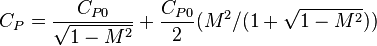

Karman-Tsien correction factor

The Karman-Tsien transformation is a nonlinear correction factor to find the pressure coefficient of a compressible, inviscid flow. It is an empirically derived correction factor that tends to slightly overestimate the magnitude of the fluid's pressure. In order to employ this correction factor, the incompressible, inviscid fluid pressure must be known from previous investigation.[5]

where

- cp is the compressible pressure coefficient

- cp0 is the incompressible pressure coefficient

- M is the Mach number.

Like the Prandtl-Glauert Rule, this is only valid for 2D flows, and only until transonic flow starts to appear.

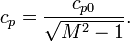

Supersonic Aerodynamics

As with subsonic aerodynamics, a compressibility correction factor can be derived by linearising the governing equations. The supersonic correction factor is similar to the Prandtl-Glauert transformation, but the terms under the square root sign are reversed.

where

- cp is the compressible pressure coefficient

- cp0 is the incompressible pressure coefficient

- M is the Mach number.

Again this is correct only for 2D flows. For validity it also requires that there is no transonic flow, which requires that the body be sufficiently slender and the freestream Mach number be sufficiently high, typically greater than 1.3.

Transonic Aerodynamics

Transonic flow typically occurs in flows with Mach numbers between 0.8 and 1.2. Under these conditions, some of the flow is supersonic and some is subsonic. At these velocities, the correction factors derived using linearized theory breaks down due to a singularity that occurs at a Mach number of 1. In addition, severe instabilities caused by the formation of local shock waves and the existence of both subsonic and supersonic flow (which behave completely differently) makes the solution of the governing equations rather difficult. However, the analysis of compressible flows in the transonic regime has led to some developments which help reduce the increases in drag caused by compressibility effects, including the use of swept wings and the Whitcomb area rule.

Internal Flows

If the flow of a fluid is confined by a surface, it is referred to as an internal flow. This includes the flow of fluids through pipes and ducts, and often arise in industrial and manufacturing processes, and is vital in the analysis of propulsion systems.

One example is in die casting or injection molding processes. This involves injecting a liquid material (such as a thermosetting plastic for injection molding or molten metal for die casting) at very high pressures into a cavity. The air that is already in the cavity is displaced very rapidly, and compressibility needs to be considered in the design of the die if problems with air entrapment are to be avoided.

Effect of area changes

Compressible flows play a big role in determining the behaviour of nozzles. Subsonic and supersonic flow react differently to changes in cross sectional area. While subsonic flow flowing through a converging duct (narrowing down from a wide diameter to a smaller diameter in the direction of the flow) will experience an increase in velocity, a supersonic flow through an identical duct will experience a decrease in velocity. In general, flow through a converging nozzle will always tend towards Mach 1. If the area convergence is great enough that the speed of sound is reached, a phenomenon known as "choking" occurs. In this case, the flow is choked, and either the flow rate of the fluid entering the pipe is limited, or shock waves form in the nozzle such that the Mach number at the point of minimum area (called the throat) remains unity. Similarly, subsonic flow through a diverging nozzle will always be slowed, and supersonic flow will accelerate. The Mach number of the flow can be directly related to the area by the relation[2]

where  and

and  are the area and Mach number at a point in the nozzle,

are the area and Mach number at a point in the nozzle,  is the ratio of specific heats, and

is the ratio of specific heats, and  is the area that would cause the flow velocity to reach a Mach number of 1 (i.e. the area at the throat, provided that the nozzle is choked).

is the area that would cause the flow velocity to reach a Mach number of 1 (i.e. the area at the throat, provided that the nozzle is choked).

Thus, for a subsonic flow to be accelerated to supersonic velocities, the nozzle needs to have a converging section in which the flow is subsonic, a throat, at which the flow velocity is the local speed of sound, and a diverging section with supersonic flow. Such an arrangement is called a de Laval nozzle, and is commonly used in propulsion systems such as rocket and supersonic jet engines.

Note that Mach 1 can be a very high speed for a hot gas, since the speed of sound varies as the square root of absolute temperature. Thus the speed reached at a nozzle throat can be far higher than the speed of sound under standard atmospheric conditions. This fact is used extensively in rocketry where hypersonic flows are required, and where propellant mixtures are deliberately chosen to further increase the sonic speed.

Effect of friction

Friction has a similar effect as an area change on compressible flow. In a pipe of constant cross sectional area in which the walls exert a frictional force on the flow, the flow velocity will tend toward the speed of sound. In other words, subsonic flow through a pipe with friction will accelerate, and supersonic flow will decelerate. If the pipe length is long enough that the flow velocity would pass through unity, then the flow chokes such that the flow exiting the pipe is at Mach 1. As with the nozzle, this is achieved either through the flow rate at the inlet being limited, or the formation of shock waves in the pipe (for supersonic flows). For the adiabatic flow of an ideal gas model, the effects of friction may be calculated using the Fanno flow model. For a constant friction factor, the model is given by[6]

where  is the Fanning friction factor,

is the Fanning friction factor,  is the required pipe length passed the point being considered that would result in the flow choking, and

is the required pipe length passed the point being considered that would result in the flow choking, and  is the hydraulic diameter of the pipe.[7]

is the hydraulic diameter of the pipe.[7]

Effect of heat transfer

Adding heat to a fluid flowing at subsonic velocities in a pipe will cause the flow to accelerate, and adding heat to supersonic flow in a pipe will cause the flow to decelerate. As with the cases of friction and area change discussed above, adding more heat than that required to reach a Mach number of 1 will result in the flow choking.

For an ideal gas in a constant area pipe, the effect of heat addition to the pipe may be calculated using the Rayleigh flow model, which describes how the Mach number varies with changes in the stagnation temperature. The stagnation temperature at a point is the temperature that the fluid would reach if it were to be slowed isentropically to stationary. As heat is added to the system, the stagnation temperature increases. The Rayleigh flow model is given by

where  and

and  represent the stagnation temperatures at the point under consideration, and at the point at which the Mach number is 1 respectively.[6]

represent the stagnation temperatures at the point under consideration, and at the point at which the Mach number is 1 respectively.[6]

Shock Tubes

In addition to measurements of rates of chemical kinetics, shock tubes have been used to measure dissociation energies and molecular relaxation rates, investigate shock wave behaviour, and they have been used in aerodynamic tests. The fluid flow in the driven gas (the gas behind the shock wave) can be used much as a wind tunnel, allowing higher temperatures and pressures replicating the conditions in the turbine sections of jet engines. However, test times are limited to a few milliseconds, either by the arrival of the contact surface or the reflected shock wave.

They have been further developed into shock tunnels, with an added nozzle and dump tank. The resultant high temperature hypersonic flow can be used to simulate atmospheric re-entry of spacecraft or hypersonic craft, again with limited testing times.

See also

- Gas dynamics

- Transonic flow

- Choked flow

- Hypersonic flow

- Fanno flow

- Rayleigh flow

- Isothermal flow

- Mach number

- Aerodynamics

- Nozzle

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 White, Frank M. (2003) Fluid Mechanics, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-119911-X. pp. 599-688.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John David Anderson (2007). Fundamentals of Aerodynamics. pp. 483–755. ISBN 978-0-07-125408-3.

- ↑ Erich Truckenbrodt: Fluidmechanik Band 2, 4. Auflage, Springer Verlag, 1996, p. 178-179

- ↑ Göthert, B.H. Plane and Three-Dimensional Flow at High Subsonic Speeds (Extension of the Prandtl Rule). NACA TM 1105, 1946.

- ↑ Shapiro (1953), The Dynamics and Thermodynamics of Compressible Fluid Flow, Volume 1, p.344

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Zucker, R.D., Biblarz, O., Fundamentals of Gas Dynamics, John Wiley & Sons, 2002.

- ↑ Hodge, B.K., and Koenig, K., Compressible Fluid Dynamics with Personal Computer Applications, Prentice Hall, 1995.

- Shapiro, Ascher H. (1953). The Dynamics and Thermodynamics of Compressible Fluid Flow, Volume 1. Ronald Press. ISBN 978-0-471-06691-0.

- Anderson, John D. (2004). Modern Compressible Flow. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-124136-1.

- Liepmann, H. W.; Roshko A. (2002). Elements of Gasdynamics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41963-0.

- von Mises, Richard (2004). Mathematical Theory of Compressible Fluid Flow. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43941-0.

- Meyer, Richard E. (2007). Introduction to Mathematical Fluid Dynamics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-45887-3.

- Saad, Michael A. (1985). Compressible Fluid Flow. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-163486-0.

- Schreier, S. (1982). Compressible Flow. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-05691-X.

- Lakshminarayana, B. (1995). Fluid Dynamics and Heat Transfer of Turbomachinery. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-85546-0.

![{\frac {A}{A^{*}}}={\frac {1}{M}}\left[{\frac {1+\left({\frac {\gamma -1}{2}}\right)M^{{2}}}{\left({\frac {\gamma +1}{2}}\right)}}\right]^{{{\frac {\gamma +1}{2(\gamma -1)}}}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/5/e/c/b5ec8b1ca9c56cea79f4de596c725440.png)

![\ 4{\frac {fL^{*}}{D_{h}}}=\left({\frac {1-M^{2}}{\gamma M^{2}}}\right)+\left({\frac {\gamma +1}{2\gamma }}\right)\ln \left[{\frac {M^{2}}{\left({\frac {2}{\gamma +1}}\right)\left(1+{\frac {\gamma -1}{2}}M^{2}\right)}}\right]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/d/9/d/c/d9dcef782325363e110c31dfd7b7b53e.png)