Complex number

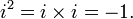

A complex number is a number that can be expressed in the form a + bi, where a and b are real numbers and i is the imaginary unit, which satisfies the equation i2 = −1.[1] In this expression, a is the real part and b is the imaginary part of the complex number. Complex numbers extend the concept of the one-dimensional number line to the two-dimensional complex plane by using the horizontal axis for the real part and the vertical axis for the imaginary part. The complex number a + bi can be identified with the point (a, b) in the complex plane. A complex number whose real part is zero is said to be purely imaginary, whereas a complex number whose imaginary part is zero is a real number. In this way the complex numbers contain the ordinary real numbers while extending them in order to solve problems that cannot be solved with real numbers alone.

As well as their use within mathematics, complex numbers have practical applications in many fields, including physics, chemistry, biology, economics, electrical engineering, and statistics. The Italian mathematician Gerolamo Cardano is the first known to have introduced complex numbers. He called them "fictitious" during his attempts to find solutions to cubic equations in the 16th century.[2]

Overview

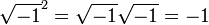

Complex numbers allow for solutions to certain equations that have no real solutions: the equation

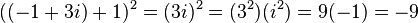

has no real solution, since the square of a real number is either 0 or positive. Complex numbers provide a solution to this problem. The idea is to extend the real numbers with the imaginary unit i where i2 = −1, so that solutions to equations like the preceding one can be found. In this case the solutions are −1 + 3i and −1 − 3i, as can be verified using the fact that i2 = −1:

In fact not only quadratic equations, but all polynomial equations with real or complex coefficients in a single variable can be solved using complex numbers.

Definition

A complex number is a number that can be expressed in the form z = a + bi, where a and b are real numbers and i is the imaginary unit, satisfying i2 = −1. For example, −3.5 + 2i is a complex number.

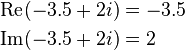

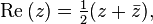

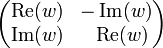

The real number a in the complex number z = a + bi is called the real part of z, and the real number b is called the imaginary part. By this convention the imaginary part does not include the imaginary unit: hence b, not bi, is the imaginary part.[3][4] The real part a is denoted by Re(z) or ℜ(z), and the imaginary part b is denoted by Im(z) or ℑ(z). For example,

Any complex number z, may be formally defined in terms of its real and imaginary parts as follows (this is sometimes known as the "Cartesian" form):

A real number a can be regarded as a complex number a + 0i with an imaginary part of zero. A pure imaginary number bi is a complex number 0 + bi whose real part is zero. It is common to write a for a + 0i and bi for 0 + bi. Moreover, when the imaginary part is negative, it is common to write a − bi with b > 0 instead of a + (−b)i, for example 3 − 4i instead of 3 + (−4)i.

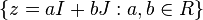

The set of all complex numbers is denoted by ℂ,  or

or  .

.

Notation

Some authors write a + ib instead of a + bi. In some disciplines, in particular electromagnetism and electrical engineering, j is used instead of i,[5] since i is frequently used for electric current. In these cases complex numbers are written as a + bj or a + jb.

Complex plane

is the rectangular expression of the point.

is the rectangular expression of the point.A complex number can be viewed as a point or position vector in a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system called the complex plane or Argand diagram (see Pedoe 1988 and Solomentsev 2001), named after Jean-Robert Argand. The numbers are conventionally plotted using the real part as the horizontal component, and imaginary part as vertical (see Figure 1). These two values used to identify a given complex number are therefore called its Cartesian, rectangular, or algebraic form.

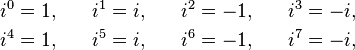

A position vector may also be defined in terms of its magnitude and direction relative to the origin. These are emphasized in a complex number's polar form. Using the polar form of the complex number in calculations may lead to a more intuitive interpretation of mathematical results. Notably, the operations of addition and multiplication take on a very natural geometric character when complex numbers are viewed as position vectors: addition corresponds to vector addition while multiplication corresponds to multiplying their magnitudes and adding their arguments (i.e. the angles they make with the x axis). Viewed in this way the multiplication of a complex number by i corresponds to rotating the position vector counterclockwise by a quarter turn (90°) about the origin:  .

.

History in brief

- Main section: History

The solution in radicals (without trigonometric functions) of a general cubic equation contains the square roots of negative numbers when all three roots are real numbers, a situation that cannot be rectified by factoring aided by the rational root test if the cubic is irreducible (the so-called casus irreducibilis). This conundrum led Italian mathematician Gerolamo Cardano to conceive of complex numbers in around 1545, though his understanding was rudimentary.

Work on the problem of general polynomials ultimately led to the fundamental theorem of algebra, which shows that with complex numbers, a solution exists to every polynomial equation of degree one or higher. Complex numbers thus form an algebraically closed field, where any polynomial equation has a root.

Many mathematicians contributed to the full development of complex numbers. The rules for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of complex numbers were developed by the Italian mathematician Rafael Bombelli.[6] A more abstract formalism for the complex numbers was further developed by the Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton, who extended this abstraction to the theory of quaternions.

Relations

Equality

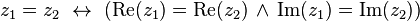

Two complex numbers are equal if and only if both their real and imaginary parts are equal. In other words:

Ordering

Because complex numbers are naturally thought of as existing on a two-dimensional plane, there is no natural linear ordering on the set of complex numbers.[7]

Elementary operations

Conjugation

in the complex plane

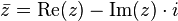

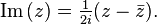

in the complex planeThe complex conjugate of the complex number z = x + yi is defined to be x − yi. It is denoted  or z*.

or z*.

Formally, for any complex number z:

Geometrically,  is the "reflection" of z about the real axis. In particular, conjugating twice gives the original complex number:

is the "reflection" of z about the real axis. In particular, conjugating twice gives the original complex number:  .

.

The real and imaginary parts of a complex number z can be extracted using the conjugate:

Moreover, a complex number is real if and only if it equals its conjugate.

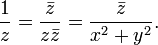

Conjugation distributes over the standard arithmetic operations:

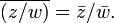

The reciprocal of a nonzero complex number z = x + yi is given by

This formula can be used to compute the multiplicative inverse of a complex number if it is given in rectangular coordinates. Inversive geometry, a branch of geometry studying reflections more general than ones about a line, can also be expressed in terms of complex numbers.

Addition and subtraction

Complex numbers are added by adding the real and imaginary parts of the summands. That is to say:

Similarly, subtraction is defined by

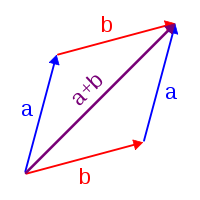

Using the visualization of complex numbers in the complex plane, the addition has the following geometric interpretation: the sum of two complex numbers A and B, interpreted as points of the complex plane, is the point X obtained by building a parallelogram three of whose vertices are O, A and B. Equivalently, X is the point such that the triangles with vertices O, A, B, and X, B, A, are congruent.

Multiplication and division

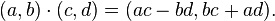

The multiplication of two complex numbers is defined by the following formula:

In particular, the square of the imaginary unit is −1:

The preceding definition of multiplication of general complex numbers follows naturally from this fundamental property of the imaginary unit. Indeed, if i is treated as a number so that di means d times i, the above multiplication rule is identical to the usual rule for multiplying two sums of two terms.

(distributive law)

(distributive law)

(commutative law of addition—the order of the summands can be changed)

(commutative law of addition—the order of the summands can be changed) (commutative and distributive laws)

(commutative and distributive laws) (fundamental property of the imaginary unit).

(fundamental property of the imaginary unit).

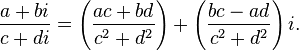

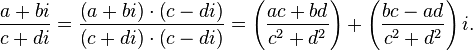

The division of two complex numbers is defined in terms of complex multiplication, which is described above, and real division. Where at least one of c and d is non-zero:

Division can be defined in this way because of the following observation:

As shown earlier, c − di is the complex conjugate of the denominator c + di. The real part c and the imaginary part d of the denominator must not both be zero for division to be defined.

Square root

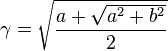

The square roots of a + bi (with b ≠ 0) are  , where

, where

and

where sgn is the signum function. This can be seen by squaring  to obtain a + bi.[8][9] Here

to obtain a + bi.[8][9] Here  is called the modulus of a + bi, and the square root with non-negative real part is called the principal square root.

is called the modulus of a + bi, and the square root with non-negative real part is called the principal square root.

Polar form

or

or  are polar expressions of the point.

are polar expressions of the point.Absolute value and argument

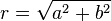

An alternative way of defining a point P in the complex plane, other than using the x- and y-coordinates, is to use the distance of the point from O, the point whose coordinates are (0, 0) (the origin), together with the angle subtended between the positive real axis and the line segment OP in a counterclockwise direction. This idea leads to the polar form of complex numbers.

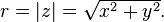

The absolute value (or modulus or magnitude) of a complex number z = x + yi is

If z is a real number (i.e., y = 0), then r = | x |. In general, by Pythagoras' theorem, r is the distance of the point P representing the complex number z to the origin.

The argument or phase of z is the angle of the radius OP with the positive real axis, and is written as  . As with the modulus, the argument can be found from the rectangular form

. As with the modulus, the argument can be found from the rectangular form  :[10]

:[10]

The value of φ must always be expressed in radians. It can increase by any integer multiple of 2π and still give the same angle. Hence, the arg function is sometimes considered as multivalued. Normally, as given above, the principal value in the interval (−π,π] is chosen. Values in the range [0,2π) are obtained by adding 2π if the value is negative. The polar angle for the complex number 0 is indeterminate, but arbitrary choice of the angle 0 is common.

The value of φ equals the result of atan2:  .

.

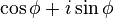

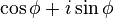

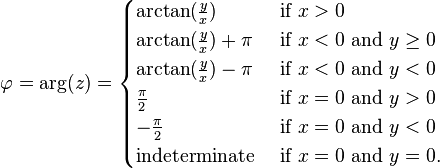

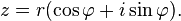

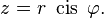

Together, r and φ give another way of representing complex numbers, the polar form, as the combination of modulus and argument fully specify the position of a point on the plane. Recovering the original rectangular co-ordinates from the polar form is done by the formula called trigonometric form

Using Euler's formula this can be written as

Using the cis function, this is sometimes abbreviated to

In angle notation, often used in electronics to represent a phasor with amplitude r and phase φ, it is written as[11]

Multiplication and division in polar form

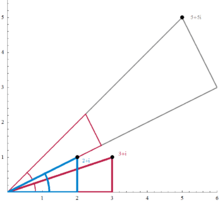

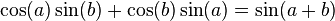

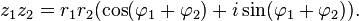

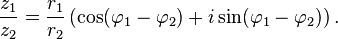

Formulas for multiplication, division and exponentiation are simpler in polar form than the corresponding formulas in Cartesian coordinates. Given two complex numbers z1 = r1(cos φ1 + i sin φ1) and z2 = r2(cos φ2 + i sin φ2), because of the well-known trigonometric identities

we may derive

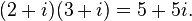

In other words, the absolute values are multiplied and the arguments are added to yield the polar form of the product. For example, multiplying by i corresponds to a quarter-turn counter-clockwise, which gives back i2 = −1. The picture at the right illustrates the multiplication of

Since the real and imaginary part of 5 + 5i are equal, the argument of that number is 45 degrees, or π/4 (in radian). On the other hand, it is also the sum of the angles at the origin of the red and blue triangles are arctan(1/3) and arctan(1/2), respectively. Thus, the formula

holds. As the arctan function can be approximated highly efficiently, formulas like this—known as Machin-like formulas—are used for high-precision approximations of π.

Similarly, division is given by

Exponentiation

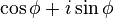

Euler's formula

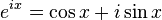

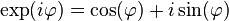

Euler's formula states that, for any real number x,

where e is the base of the natural logarithm. This can be proved by observing that

and so on, and by considering the Taylor series expansions of eix, cos(x) and sin(x):

The rearrangement of terms is justified because each series is absolutely convergent.

Natural logarithm

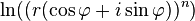

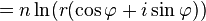

Euler's formula allows us to observe that, for any complex number

where r is a nonnegative real number, one possible value for z's natural logarithm is

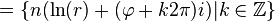

Because cos and sin are periodic functions, the natural logarithm may be considered a multi-valued function, with:

Integer and fractional exponents

We may use the identity

to define complex exponentiation, which is likewise multi-valued:

Where n is an integer, this simplifies to de Moivre's formula:

The nth roots of z are given by

for any integer k satisfying 0 ≤ k ≤ n − 1. Here n√r is the usual (positive) nth root of the positive real number r. While the nth root of a positive real number r is chosen to be the positive real number c satisfying cn = x there is no natural way of distinguishing one particular complex nth root of a complex number. Therefore, the nth root of z is considered as a multivalued function (in z), as opposed to a usual function f, for which f(z) is a uniquely defined number. Formulas such as

(which holds for positive real numbers), do in general not hold for complex numbers.

Properties

Field structure

The set C of complex numbers is a field. Briefly, this means that the following facts hold: first, any two complex numbers can be added and multiplied to yield another complex number. Second, for any complex number z, its additive inverse −z is also a complex number; and third, every nonzero complex number has a reciprocal complex number. Moreover, these operations satisfy a number of laws, for example the law of commutativity of addition and multiplication for any two complex numbers z1 and z2:

These two laws and the other requirements on a field can be proven by the formulas given above, using the fact that the real numbers themselves form a field.

Unlike the reals, C is not an ordered field, that is to say, it is not possible to define a relation z1 < z2 that is compatible with the addition and multiplication. In fact, in any ordered field, the square of any element is necessarily positive, so i2 = −1 precludes the existence of an ordering on C.

When the underlying field for a mathematical topic or construct is the field of complex numbers, the thing's name is usually modified to reflect that fact. For example: complex analysis, complex matrix, complex polynomial, and complex Lie algebra.

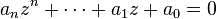

Solutions of polynomial equations

Given any complex numbers (called coefficients) a0, …, an, the equation

has at least one complex solution z, provided that at least one of the higher coefficients a1, …, an is nonzero. This is the statement of the fundamental theorem of algebra. Because of this fact, C is called an algebraically closed field. This property does not hold for the field of rational numbers Q (the polynomial x2 − 2 does not have a rational root, since √2 is not a rational number) nor the real numbers R (the polynomial x2 + a does not have a real root for a > 0, since the square of x is positive for any real number x).

There are various proofs of this theorem, either by analytic methods such as Liouville's theorem, or topological ones such as the winding number, or a proof combining Galois theory and the fact that any real polynomial of odd degree has at least one root.

Because of this fact, theorems that hold for any algebraically closed field, apply to C. For example, any non-empty complex square matrix has at least one (complex) eigenvalue.

Algebraic characterization

The field C has the following three properties: first, it has characteristic 0. This means that 1 + 1 + ⋯ + 1 ≠ 0 for any number of summands (all of which equal one). Second, its transcendence degree over Q, the prime field of C, is the cardinality of the continuum. Third, it is algebraically closed (see above). It can be shown that any field having these properties is isomorphic (as a field) to C. For example, the algebraic closure of Qp also satisfies these three properties, so these two fields are isomorphic. Also, C is isomorphic to the field of complex Puiseux series. However, specifying an isomorphism requires the axiom of choice. Another consequence of this algebraic characterization is that C contains many proper subfields that are isomorphic to C.

Characterization as a topological field

The preceding characterization of C describes the algebraic aspects of C, only. That is to say, the properties of nearness and continuity, which matter in areas such as analysis and topology, are not dealt with. The following description of C as a topological field (that is, a field that is equipped with a topology, which allows the notion of convergence) does take into account the topological properties. C contains a subset P (namely the set of positive real numbers) of nonzero elements satisfying the following three conditions:

- P is closed under addition, multiplication and taking inverses.

- If x and y are distinct elements of P, then either x − y or y − x is in P.

- If S is any nonempty subset of P, then S + P = x + P for some x in C.

Moreover, C has a nontrivial involutive automorphism x ↦ x* (namely the complex conjugation), such that x x* is in P for any nonzero x in C.

Any field F with these properties can be endowed with a topology by taking the sets B(x, p) = { y | p − (y − x)(y − x)* ∈ P } as a base, where x ranges over the field and p ranges over P. With this topology F is isomorphic as a topological field to C.

The only connected locally compact topological fields are R and C. This gives another characterization of C as a topological field, since C can be distinguished from R because the nonzero complex numbers are connected, while the nonzero real numbers are not.

Formal construction

Formal development

Above, complex numbers have been defined by introducing i, the imaginary unit, as a symbol. More rigorously, the set C of complex numbers can be defined as the set R2 of ordered pairs (a, b) of real numbers. In this notation, the above formulas for addition and multiplication read

It is then just a matter of notation to express (a, b) as a + bi.

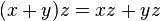

Though this low-level construction does accurately describe the structure of the complex numbers, the following equivalent definition reveals the algebraic nature of C more immediately. This characterization relies on the notion of fields and polynomials. A field is a set endowed with an addition, subtraction, multiplication and division operations that behave as is familiar from, say, rational numbers. For example, the distributive law

must hold for any three elements x, y and z of a field. The set R of real numbers does form a field. A polynomial p(X) with real coefficients is an expression of the form

,

,

where the a0, …, an are real numbers. The usual addition and multiplication of polynomials endows the set R[X] of all such polynomials with a ring structure. This ring is called polynomial ring.

The quotient ring R[X]/(X 2 + 1) can be shown to be a field. This extension field contains two square roots of −1, namely (the cosets of) X and −X, respectively. (The cosets of) 1 and X form a basis of R[X]/(X 2 + 1) as a real vector space, which means that each element of the extension field can be uniquely written as a linear combination in these two elements. Equivalently, elements of the extension field can be written as ordered pairs (a, b) of real numbers. Moreover, the above formulas for addition etc. correspond to the ones yielded by this abstract algebraic approach – the two definitions of the field C are said to be isomorphic (as fields). Together with the above-mentioned fact that C is algebraically closed, this also shows that C is an algebraic closure of R.

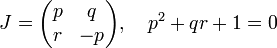

Matrix representation of complex numbers

Complex numbers a + ib can also be represented by 2 × 2 matrices that have the following form:

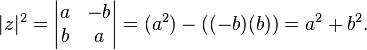

Here the entries a and b are real numbers. The sum and product of two such matrices is again of this form, and the sum and product of complex numbers corresponds to the sum and product of such matrices. The geometric description of the multiplication of complex numbers can also be phrased in terms of rotation matrices by using this correspondence between complex numbers and such matrices. Moreover, the square of the absolute value of a complex number expressed as a matrix is equal to the determinant of that matrix:

The conjugate  corresponds to the transpose of the matrix.

corresponds to the transpose of the matrix.

Though this representation of complex numbers with matrices is the most common, many other representations arise from matrices other than  that square to the negative of the identity matrix. See the article on 2 × 2 real matrices for other representations of complex numbers.

that square to the negative of the identity matrix. See the article on 2 × 2 real matrices for other representations of complex numbers.

Complex analysis

The study of functions of a complex variable is known as complex analysis and has enormous practical use in applied mathematics as well as in other branches of mathematics. Often, the most natural proofs for statements in real analysis or even number theory employ techniques from complex analysis (see prime number theorem for an example). Unlike real functions, which are commonly represented as two-dimensional graphs, complex functions have four-dimensional graphs and may usefully be illustrated by color-coding a three-dimensional graph to suggest four dimensions, or by animating the complex function's dynamic transformation of the complex plane.

Complex exponential and related functions

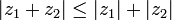

The notions of convergent series and continuous functions in (real) analysis have natural analogs in complex analysis. A sequence of complex numbers is said to converge if and only if its real and imaginary parts do. This is equivalent to the (ε, δ)-definition of limits, where the absolute value of real numbers is replaced by the one of complex numbers. From a more abstract point of view, C, endowed with the metric

is a complete metric space, which notably includes the triangle inequality

for any two complex numbers z1 and z2.

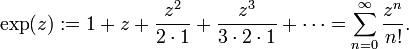

Like in real analysis, this notion of convergence is used to construct a number of elementary functions: the exponential function exp(z), also written ez, is defined as the infinite series

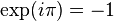

and the series defining the real trigonometric functions sine and cosine, as well as hyperbolic functions such as sinh also carry over to complex arguments without change. Euler's identity states:

for any real number φ, in particular

Unlike in the situation of real numbers, there is an infinitude of complex solutions z of the equation

for any complex number w ≠ 0. It can be shown that any such solution z—called complex logarithm of a—satisfies

where arg is the argument defined above, and ln the (real) natural logarithm. As arg is a multivalued function, unique only up to a multiple of 2π, log is also multivalued. The principal value of log is often taken by restricting the imaginary part to the interval (−π,π].

Complex exponentiation zω is defined as

Consequently, they are in general multi-valued. For ω = 1 / n, for some natural number n, this recovers the non-uniqueness of nth roots mentioned above.

Complex numbers, unlike real numbers, do not in general satisfy the unmodified power and logarithm identities, particularly when naïvely treated as single-valued functions; see failure of power and logarithm identities. For example they do not satisfy

Both sides of the equation are multivalued by the definition of complex exponentiation given here, and the values on the left are a subset of those on the right.

Holomorphic functions

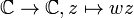

A function f : C → C is called holomorphic if it satisfies the Cauchy–Riemann equations. For example, any R-linear map C → C can be written in the form

with complex coefficients a and b. This map is holomorphic if and only if b = 0. The second summand  is real-differentiable, but does not satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations.

is real-differentiable, but does not satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations.

Complex analysis shows some features not apparent in real analysis. For example, any two holomorphic functions f and g that agree on an arbitrarily small open subset of C necessarily agree everywhere. Meromorphic functions, functions that can locally be written as f(z)/(z − z0)n with a holomorphic function f, still share some of the features of holomorphic functions. Other functions have essential singularities, such as sin(1/z) at z = 0.

Applications

Complex numbers have essential concrete applications in a variety of scientific and related areas such as signal processing, control theory, electromagnetism, fluid dynamics, quantum mechanics, cartography, and vibration analysis. Some applications of complex numbers are:

Control theory

In control theory, systems are often transformed from the time domain to the frequency domain using the Laplace transform. The system's poles and zeros are then analyzed in the complex plane. The root locus, Nyquist plot, and Nichols plot techniques all make use of the complex plane.

In the root locus method, it is especially important whether the poles and zeros are in the left or right half planes, i.e. have real part greater than or less than zero. If a linear, time-invariant (LTI) system has poles that are

- in the right half plane, it will be unstable,

- all in the left half plane, it will be stable,

- on the imaginary axis, it will have marginal stability.

If a system has zeros in the right half plane, it is a nonminimum phase system.

Improper integrals

In applied fields, complex numbers are often used to compute certain real-valued improper integrals, by means of complex-valued functions. Several methods exist to do this; see methods of contour integration.

Fluid dynamics

In fluid dynamics, complex functions are used to describe potential flow in two dimensions.

Dynamic equations

In differential equations, it is common to first find all complex roots r of the characteristic equation of a linear differential equation or equation system and then attempt to solve the system in terms of base functions of the form f(t) = ert. Likewise, in difference equations, the complex roots r of the characteristic equation of the difference equation system are used, to attempt to solve the system in terms of base functions of the form f(t) = r t.

Electromagnetism and electrical engineering

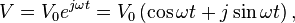

In electrical engineering, the Fourier transform is used to analyze varying voltages and currents. The treatment of resistors, capacitors, and inductors can then be unified by introducing imaginary, frequency-dependent resistances for the latter two and combining all three in a single complex number called the impedance. This approach is called phasor calculus.

In electrical engineering, the imaginary unit is denoted by j, to avoid confusion with I which is generally in use to denote electric current.

Since the voltage in an AC circuit is oscillating, it can be represented as

To obtain the measurable quantity, the real part is taken:

See for example.[12]

Signal analysis

Complex numbers are used in signal analysis and other fields for a convenient description for periodically varying signals. For given real functions representing actual physical quantities, often in terms of sines and cosines, corresponding complex functions are considered of which the real parts are the original quantities. For a sine wave of a given frequency, the absolute value | z | of the corresponding z is the amplitude and the argument arg(z) the phase.

If Fourier analysis is employed to write a given real-valued signal as a sum of periodic functions, these periodic functions are often written as complex valued functions of the form

where ω represents the angular frequency and the complex number z encodes the phase and amplitude as explained above.

This use is also extended into digital signal processing and digital image processing, which utilize digital versions of Fourier analysis (and wavelet analysis) to transmit, compress, restore, and otherwise process digital audio signals, still images, and video signals.

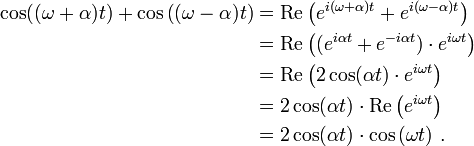

Another example, relevant to the two side bands of amplitude modulation of AM radio, is:

Quantum mechanics

The complex number field is intrinsic to the mathematical formulations of quantum mechanics, where complex Hilbert spaces provide the context for one such formulation that is convenient and perhaps most standard. The original foundation formulas of quantum mechanics – the Schrödinger equation and Heisenberg's matrix mechanics – make use of complex numbers.

Relativity

In special and general relativity, some formulas for the metric on spacetime become simpler if one takes the time variable to be imaginary. (This is no longer standard in classical relativity, but is used in an essential way in quantum field theory.) Complex numbers are essential to spinors, which are a generalization of the tensors used in relativity.

Geometry

Fractals

Certain fractals are plotted in the complex plane, e.g. the Mandelbrot set and Julia sets.

Triangles

Every triangle has a unique Steiner inellipse—an ellipse inside the triangle and tangent to the midpoints of the three sides of the triangle. The foci of a triangle's Steiner inellipse can be found as follows, according to Marden's theorem:[13][14] Denote the triangle's vertices in the complex plane as a = xA + yAi, b = xB + yBi, and c = xC + yCi. Write the cubic equation  , take its derivative, and equate the (quadratic) derivative to zero. Marden's Theorem says that the solutions of this equation are the complex numbers denoting the locations of the two foci of the Steiner inellipse.

, take its derivative, and equate the (quadratic) derivative to zero. Marden's Theorem says that the solutions of this equation are the complex numbers denoting the locations of the two foci of the Steiner inellipse.

Algebraic number theory

As mentioned above, any nonconstant polynomial equation (in complex coefficients) has a solution in C. A fortiori, the same is true if the equation has rational coefficients. The roots of such equations are called algebraic numbers – they are a principal object of study in algebraic number theory. Compared to Q, the algebraic closure of Q, which also contains all algebraic numbers, C has the advantage of being easily understandable in geometric terms. In this way, algebraic methods can be used to study geometric questions and vice versa. With algebraic methods, more specifically applying the machinery of field theory to the number field containing roots of unity, it can be shown that it is not possible to construct a regular nonagon using only compass and straightedge – a purely geometric problem.

Another example are Pythagorean triples (a, b, c), that is to say integers satisfying

(which implies that the triangle having side lengths a, b, and c is a right triangle). They can be studied by considering Gaussian integers, that is, numbers of the form x + iy, where x and y are integers.

Analytic number theory

Analytic number theory studies numbers, often integers or rationals, by taking advantage of the fact that they can be regarded as complex numbers, in which analytic methods can be used. This is done by encoding number-theoretic information in complex-valued functions. For example, the Riemann zeta-function ζ(s) is related to the distribution of prime numbers.

History

The earliest fleeting reference to square roots of negative numbers can perhaps be said to occur in the work of the Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria in the 1st century AD, where in his Stereometrica he considers, apparently in error, the volume of an impossible frustum of a pyramid to arrive at the term √81 − 144 in his calculations, although negative quantities were not conceived of in Hellenistic mathematics and Heron merely replaced it by its positive.[15]

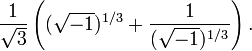

The impetus to study complex numbers proper first arose in the 16th century when algebraic solutions for the roots of cubic and quartic polynomials were discovered by Italian mathematicians (see Niccolo Fontana Tartaglia, Gerolamo Cardano). It was soon realized that these formulas, even if one was only interested in real solutions, sometimes required the manipulation of square roots of negative numbers. As an example, Tartaglia's formula for a cubic equation of the form  [16] gives the solution to the equation x3 = x as

[16] gives the solution to the equation x3 = x as

At first glance this looks like nonsense. However formal calculations with complex numbers show that the equation z3 = i has solutions −i,  and

and  . Substituting these in turn for

. Substituting these in turn for  in Tartaglia's cubic formula and simplifying, one gets 0, 1 and −1 as the solutions of x3 − x = 0. Of course this particular equation can be solved at sight but it does illustrate that when general formulas are used to solve cubic equations with real roots then, as later mathematicians showed rigorously, the use of complex numbers is unavoidable. Rafael Bombelli was the first to explicitly address these seemingly paradoxical solutions of cubic equations and developed the rules for complex arithmetic trying to resolve these issues.

in Tartaglia's cubic formula and simplifying, one gets 0, 1 and −1 as the solutions of x3 − x = 0. Of course this particular equation can be solved at sight but it does illustrate that when general formulas are used to solve cubic equations with real roots then, as later mathematicians showed rigorously, the use of complex numbers is unavoidable. Rafael Bombelli was the first to explicitly address these seemingly paradoxical solutions of cubic equations and developed the rules for complex arithmetic trying to resolve these issues.

[...] quelquefois seulement imaginaires c’est-à-dire que l’on peut toujours en imaginer autant que j'ai dit en chaque équation, mais qu’il n’y a quelquefois aucune quantité qui corresponde à celle qu’on imagine.A further source of confusion was that the equation

([...] sometimes only imaginary, that is one can imagine as many as I said in each equation, but sometimes there exists no quantity that matches that which we imagine.)

seemed to be capriciously inconsistent with the algebraic identity

seemed to be capriciously inconsistent with the algebraic identity  , which is valid for non-negative real numbers a and b, and which was also used in complex number calculations with one of a, b positive and the other negative. The incorrect use of this identity (and the related identity

, which is valid for non-negative real numbers a and b, and which was also used in complex number calculations with one of a, b positive and the other negative. The incorrect use of this identity (and the related identity  ) in the case when both a and b are negative even bedeviled Euler. This difficulty eventually led to the convention of using the special symbol i in place of √−1 to guard against this mistake.[citation needed] Even so Euler considered it natural to introduce students to complex numbers much earlier than we do today. In his elementary algebra text book, Elements of Algebra, he introduces these numbers almost at once and then uses them in a natural way throughout.

) in the case when both a and b are negative even bedeviled Euler. This difficulty eventually led to the convention of using the special symbol i in place of √−1 to guard against this mistake.[citation needed] Even so Euler considered it natural to introduce students to complex numbers much earlier than we do today. In his elementary algebra text book, Elements of Algebra, he introduces these numbers almost at once and then uses them in a natural way throughout.

In the 18th century complex numbers gained wider use, as it was noticed that formal manipulation of complex expressions could be used to simplify calculations involving trigonometric functions. For instance, in 1730 Abraham de Moivre noted that the complicated identities relating trigonometric functions of an integer multiple of an angle to powers of trigonometric functions of that angle could be simply re-expressed by the following well-known formula which bears his name, de Moivre's formula:

In 1748 Leonhard Euler went further and obtained Euler's formula of complex analysis:

by formally manipulating complex power series and observed that this formula could be used to reduce any trigonometric identity to much simpler exponential identities.

The idea of a complex number as a point in the complex plane (above) was first described by Caspar Wessel in 1799, although it had been anticipated as early as 1685 in Wallis's De Algebra tractatus.

Wessel's memoir appeared in the Proceedings of the Copenhagen Academy but went largely unnoticed. In 1806 Jean-Robert Argand independently issued a pamphlet on complex numbers and provided a rigorous proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra. Gauss had earlier published an essentially topological proof of the theorem in 1797 but expressed his doubts at the time about "the true metaphysics of the square root of −1". It was not until 1831 that he overcame these doubts and published his treatise on complex numbers as points in the plane, largely establishing modern notation and terminology. The English mathematician G. H. Hardy remarked that Gauss was the first mathematician to use complex numbers in 'a really confident and scientific way' although mathematicians such as Niels Henrik Abel and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi were necessarily using them routinely before Gauss published his 1831 treatise.[18] Augustin Louis Cauchy and Bernhard Riemann together brought the fundamental ideas of complex analysis to a high state of completion, commencing around 1825 in Cauchy's case.

The common terms used in the theory are chiefly due to the founders. Argand called  the direction factor, and

the direction factor, and  the modulus; Cauchy (1828) called

the modulus; Cauchy (1828) called  the reduced form (l'expression réduite) and apparently introduced the term argument; Gauss used i for

the reduced form (l'expression réduite) and apparently introduced the term argument; Gauss used i for  , introduced the term complex number for a + bi, and called a2 + b2 the norm. The expression direction coefficient, often used for

, introduced the term complex number for a + bi, and called a2 + b2 the norm. The expression direction coefficient, often used for  , is due to Hankel (1867), and absolute value, for modulus, is due to Weierstrass.

, is due to Hankel (1867), and absolute value, for modulus, is due to Weierstrass.

Later classical writers on the general theory include Richard Dedekind, Otto Hölder, Felix Klein, Henri Poincaré, Hermann Schwarz, Karl Weierstrass and many others.

Generalizations and related notions

The process of extending the field R of reals to C is known as Cayley–Dickson construction. It can be carried further to higher dimensions, yielding the quaternions H and octonions O which (as a real vector space) are of dimension 4 and 8, respectively. However, with increasing dimension, the algebraic properties familiar from real and complex numbers vanish: the quaternions are only a skew field, i.e. for some x, y: x·y ≠ y·x for two quaternions, the multiplication of octonions fails (in addition to not being commutative) to be associative: for some x, y, z: (x·y)·z ≠ x·(y·z). However, all of these are normed division algebras over R. By Hurwitz's theorem they are the only ones. The next step in the Cayley–Dickson construction, the sedenions fail to have this structure.

The Cayley–Dickson construction is closely related to the regular representation of C, thought of as an R-algebra (an R-vector space with a multiplication), with respect to the basis (1, i). This means the following: the R-linear map

for some fixed complex number w can be represented by a 2 × 2 matrix (once a basis has been chosen). With respect to the basis (1, i), this matrix is

i.e., the one mentioned in the section on matrix representation of complex numbers above. While this is a linear representation of C in the 2 × 2 real matrices, it is not the only one. Any matrix

has the property that its square is the negative of the identity matrix: J2 = −I. Then

is also isomorphic to the field C, and gives an alternative complex structure on R2. This is generalized by the notion of a linear complex structure.

Hypercomplex numbers also generalize R, C, H, and O. For example this notion contains the split-complex numbers, which are elements of the ring R[x]/(x2 − 1) (as opposed to R[x]/(x2 + 1)). In this ring, the equation a2 = 1 has four solutions.

The field R is the completion of Q, the field of rational numbers, with respect to the usual absolute value metric. Other choices of metrics on Q lead to the fields Qp of p-adic numbers (for any prime number p), which are thereby analogous to R. There are no other nontrivial ways of completing Q than R and Qp, by Ostrowski's theorem. The algebraic closure  of Qp still carry a norm, but (unlike C) are not complete with respect to it. The completion

of Qp still carry a norm, but (unlike C) are not complete with respect to it. The completion  of

of  turns out to be algebraically closed. This field is called p-adic complex numbers by analogy.

turns out to be algebraically closed. This field is called p-adic complex numbers by analogy.

The fields R and Qp and their finite field extensions, including C, are local fields.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Complex numbers. |

- Circular motion using complex numbers

- Complex base systems

- Complex geometry

- Complex square root

- Domain coloring

- Eisenstein integer

- Euler's identity

- Gaussian integer

- Mandelbrot set

- Quaternion

- Riemann sphere (extended complex plane)

- Root of unity

Notes

- ↑ Charles P. McKeague (2011), Elementary Algebra, Brooks/Cole, p. 524, ISBN 978-0-8400-6421-9

- ↑ Burton (1995, p. 294)

- ↑ Complex Variables (2nd Edition), M.R. Spiegel, S. Lipschutz, J.J. Schiller, D. Spellman, Schaum's Outline Series, Mc Graw Hill (USA), ISBN 978-0-07-161569-3

- ↑ Aufmann, Richard N.; Barker, Vernon C.; Nation, Richard D. (2007), College Algebra and Trigonometry (6 ed.), Cengage Learning, p. 66, ISBN 0-618-82515-0, Chapter P, p. 66

- ↑ Brown, James Ward; Churchill, Ruel V. (1996), Complex variables and applications (6th ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 2, ISBN 0-07-912147-0, "In electrical engineering, the letter j is used instead of i."

- ↑ Katz (2004, §9.1.4)

- ↑ http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ComplexNumber.html

- ↑ Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A. (1964), Handbook of mathematical functions with formulas, graphs, and mathematical tables, Courier Dover Publications, p. 17, ISBN 0-486-61272-4, Section 3.7.26, p. 17

- ↑ Cooke, Roger (2008), Classical algebra: its nature, origins, and uses, John Wiley and Sons, p. 59, ISBN 0-470-25952-3, Extract: page 59

- ↑ Kasana, H.S. (2005), Complex Variables: Theory And Applications (2nd ed.), PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd, p. 14, ISBN 81-203-2641-5, Extract of chapter 1, page 14

- ↑ Nilsson, James William; Riedel, Susan A. (2008), Electric circuits (8th ed.), Prentice Hall, p. 338, ISBN 0-13-198925-1, Chapter 9, page 338

- ↑ Electromagnetism (2nd edition), I.S. Grant, W.R. Phillips, Manchester Physics Series, 2008 ISBN 0-471-92712-0

- ↑ Kalman, Dan (2008a), "An Elementary Proof of Marden's Theorem", The American Mathematical Monthly 115: 330–338, ISSN 0002-9890

- ↑ Kalman, Dan (2008b), "The Most Marvelous Theorem in Mathematics", Journal of Online Mathematics and its Applications

- ↑ Nahin, Paul J. (2007), An Imaginary Tale: The Story of √−1, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12798-9, retrieved 20 April 2011

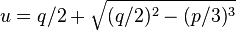

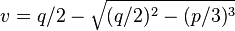

- ↑ In modern notation, Tartaglia's solution is based on expanding the cube of the sum of two cube roots:

![\left({\sqrt[ {3}]{u}}+{\sqrt[ {3}]{v}}\right)^{3}=3{\sqrt[ {3}]{uv}}\left({\sqrt[ {3}]{u}}+{\sqrt[ {3}]{v}}\right)+u+v](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/a/2/3/5a232bf5fa1ce1247bc14b4a3a17e598.png) With

With ![x={\sqrt[ {3}]{u}}+{\sqrt[ {3}]{v}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/f/a/a/1/faa100ad3eb7a2cc8fb7d885605e231b.png) ,

, ![p=3{\sqrt[ {3}]{uv}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/9/4/3/c/943c7042e6e8d1fc3abf0dfe9df9df5b.png) ,

,  , u and v can be expressed in terms of p and q as

, u and v can be expressed in terms of p and q as  and

and  , respectively. Therefore,

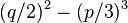

, respectively. Therefore, ![x={\sqrt[ {3}]{q/2+{\sqrt {(q/2)^{2}-(p/3)^{3}}}}}+{\sqrt[ {3}]{q/2-{\sqrt {(q/2)^{2}-(p/3)^{3}}}}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/a/8/0/c/a80c9a322a0793c97824edd09480c1da.png) . When

. When  is negative (casus irreducibilis), the second cube root should be regarded as the complex conjugate of the first one.

is negative (casus irreducibilis), the second cube root should be regarded as the complex conjugate of the first one. - ↑ Descartes, René (1954) [1637], La Géométrie | The Geometry of René Descartes with a facsimile of the first edition, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60068-8, retrieved 20 April 2011

- ↑ Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (2000) [1938], An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers, OUP Oxford, p. 189 (fourth edition), ISBN 0-19-921986-9

References

Mathematical references

- Ahlfors, Lars (1979), Complex analysis (3rd ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-000657-7

- Conway, John B. (1986), Functions of One Complex Variable I, Springer, ISBN 0-387-90328-3

- Joshi, Kapil D. (1989), Foundations of Discrete Mathematics, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-21152-6

- Pedoe, Dan (1988), Geometry: A comprehensive course, Dover, ISBN 0-486-65812-0

- Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007), "Section 5.5 Complex Arithmetic", Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8

- Solomentsev, E.D. (2001), "Complex number", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

Historical references

- Burton, David M. (1995), The History of Mathematics (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-009465-9

- Katz, Victor J. (2004), A History of Mathematics, Brief Version, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-321-16193-2

- Nahin, Paul J. (1998), An Imaginary Tale: The Story of

(hardcover ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-02795-1

(hardcover ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-02795-1

- A gentle introduction to the history of complex numbers and the beginnings of complex analysis.

- H.-D. Ebbinghaus ... (1991), Numbers (hardcover ed.), Springer, ISBN 0-387-97497-0

- An advanced perspective on the historical development of the concept of number.

Further reading

- The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe, by Roger Penrose; Alfred A. Knopf, 2005; ISBN 0-679-45443-8. Chapters 4–7 in particular deal extensively (and enthusiastically) with complex numbers.

- Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra, by John Derbyshire; Joseph Henry Press; ISBN 0-309-09657-X (hardcover 2006). A very readable history with emphasis on solving polynomial equations and the structures of modern algebra.

- Visual Complex Analysis, by Tristan Needham; Clarendon Press; ISBN 0-19-853447-7 (hardcover, 1997). History of complex numbers and complex analysis with compelling and useful visual interpretations.

- Conway, John B., Functions of One Complex Variable I (Graduate Texts in Mathematics), Springer; 2 edition (September 12, 2005). ISBN 0-387-90328-3.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning materials about Complex Numbers |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Calculus/Complex numbers |

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Complex number", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Introduction to Complex Numbers from Khan Academy

- Imaginary Numbers on In Our Time at the BBC.

- Euler's work on Complex Roots of Polynomials at Convergence. MAA Mathematical Sciences Digital Library.

- John and Betty's Journey Through Complex Numbers

- Dimensions: a math film. Chapter 5 presents an introduction to complex arithmetic and stereographic projection. Chapter 6 discusses transformations of the complex plane, Julia sets, and the Mandelbrot set.

| |||||||||||

![{\begin{aligned}e^{{ix}}&{}=1+ix+{\frac {(ix)^{2}}{2!}}+{\frac {(ix)^{3}}{3!}}+{\frac {(ix)^{4}}{4!}}+{\frac {(ix)^{5}}{5!}}+{\frac {(ix)^{6}}{6!}}+{\frac {(ix)^{7}}{7!}}+{\frac {(ix)^{8}}{8!}}+\cdots \\[8pt]&{}=1+ix-{\frac {x^{2}}{2!}}-{\frac {ix^{3}}{3!}}+{\frac {x^{4}}{4!}}+{\frac {ix^{5}}{5!}}-{\frac {x^{6}}{6!}}-{\frac {ix^{7}}{7!}}+{\frac {x^{8}}{8!}}+\cdots \\[8pt]&{}=\left(1-{\frac {x^{2}}{2!}}+{\frac {x^{4}}{4!}}-{\frac {x^{6}}{6!}}+{\frac {x^{8}}{8!}}-\cdots \right)+i\left(x-{\frac {x^{3}}{3!}}+{\frac {x^{5}}{5!}}-{\frac {x^{7}}{7!}}+\cdots \right)\\[8pt]&{}=\cos x+i\sin x\ .\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/8/7/9/9/8799ab90dd91d47cf82ea7b449556230.png)

![{\sqrt[ {n}]{z}}={\sqrt[ {n}]r}\left(\cos \left({\frac {\varphi +2k\pi }{n}}\right)+i\sin \left({\frac {\varphi +2k\pi }{n}}\right)\right)](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/d/5/d/2d5dffb3ae03a3754ade07b826b09eb1.png)

![{\sqrt[ {n}]{z^{n}}}=z](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/f/7/3/7/f737db4a1e6de78b87bd15fff1d48c9b.png)

![{\mathrm {Re}}(V)={\mathrm {Re}}\left[V_{0}e^{{j\omega t}}\right]=V_{0}\cos \omega t.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/3/a/3/5/3a35d92126d50a83849567cf692b4be5.png)

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)