Combustion

Combustion /kəmˈbʌs.tʃən/ or burning[1] is the sequence of exothermic chemical reactions between a fuel and an oxidant accompanied by the production of heat and conversion of chemical species. The release of heat can produce light in the form of either glowing or a flame.

In a complete combustion reaction, a compound reacts with an oxidizing element, such as oxygen or fluorine, and the products are compounds of each element in the fuel with the oxidizing element. For example:

- CH4(g) + 2O2(g) → CO2(g) + 2H2O(g)

The standard enthalpy of reaction for methane combustion at 298.15 K and 1 atm is −802 kJ/mol.[2] A simple example can be seen in the combustion of hydrogen and oxygen, a reaction commonly used to fuel rocket engines:

- 2H2(g) + O2(g) → 2H2O(g)

The result is water vapor, with a standard enthalpy of reaction at 298.15 K and 1 atm of −242 kJ/mol.[2]

Complete combustion is almost impossible to achieve. As actual combustion reactions come to equilibrium, a wide variety of major and minor species will be present, such as carbon monoxide, hydrogen and even carbon (soot or ash). Additionally, any combustion at high temperatures in atmospheric air, which is 78 percent nitrogen, will also create small amounts of several nitrogen oxides, commonly referred to as NO

x.

Combustion need not always involve oxygen; e.g., hydrogen burns in chlorine to form hydrogen chloride with the liberation of heat and light characteristic of combustion.

Types

Complete vs. incomplete

Complete

In complete combustion, the reactant burns in oxygen, producing a limited number of products. When a hydrocarbon burns in oxygen, the reaction will primarily yield carbon dioxide and water. When elements are burned, the products are primarily the most common oxides. Carbon will yield carbon dioxide, sulfur will yield sulfur dioxide, and iron will yield iron(III) oxide. Nitrogen is not considered to be a combustible substance when oxygen is the oxidant, but small amounts of various nitrogen oxides (commonly designated NO

x species) form when air is the oxidant.

Combustion is not necessarily favorable to the maximum degree of oxidation, and it can be temperature-dependent. For example, sulfur trioxide is not produced quantitatively by the combustion of sulfur. NOx species appear in significant amounts above about 2,800 °F (1,540 °C), and more is produced at higher temperatures. The amount of NOx is also a function of oxygen excess.[3]

In most industrial applications and in fires, air is the source of oxygen (O

2). In air, each mole of oxygen is mixed with approximately 3.71 mol of nitrogen. Nitrogen does not take part in combustion, but at high temperatures some nitrogen will be converted to NO

x (mostly NO, with much smaller amounts of NO

2). On the other hand, when there is insufficient oxygen to completely combust the fuel, some fuel carbon is converted to carbon monoxide and some of the hydrogen remains unreacted. A more complete set of equations for the combustion of a hydrocarbon in air therefore requires an additional calculation for the distribution of oxygen between the carbon and hydrogen in the fuel.

The amount of air required for complete combustion to take place is known as theoretical air. However, in practice the air used is 2-3x that of theoretical air.

Incomplete

Incomplete combustion will occur when there is not enough oxygen to allow the fuel to react completely to produce carbon dioxide and water. It also happens when the combustion is quenched by a heat sink, such as a solid surface or flame trap.

For most fuels, such as diesel oil, coal or wood, pyrolysis occurs before combustion. In incomplete combustion, products of pyrolysis remain unburnt and contaminate the smoke with noxious particulate matter and gases. Partially oxidized compounds are also a concern; partial oxidation of ethanol can produce harmful acetaldehyde, and carbon can produce toxic carbon monoxide.

The quality of combustion can be improved by the designs of combustion devices, such as burners and internal combustion engines. Further improvements are achievable by catalytic after-burning devices (such as catalytic converters) or by the simple partial return of the exhaust gases into the combustion process. Such devices are required by environmental legislation for cars in most countries, and may be necessary to enable large combustion devices, such as thermal power stations, to reach legal emission standards.

The degree of combustion can be measured and analyzed with test equipment. HVAC contractors, firemen and engineers use combustion analyzers to test the efficiency of a burner during the combustion process. In addition, the efficiency of an internal combustion engine can be measured in this way, and some U.S. states and local municipalities use combustion analysis to define and rate the efficiency of vehicles on the road today.

Smouldering/Slow

Smouldering is the slow, low-temperature, flameless form of combustion, sustained by the heat evolved when oxygen directly attacks the surface of a condensed-phase fuel. It is a typically incomplete combustion reaction. Solid materials that can sustain a smouldering reaction include coal, cellulose, wood, cotton, tobacco, peat, duff, humus, synthetic foams, charring polymers (including polyurethane foam), and dust. Common examples of smouldering phenomena are the initiation of residential fires on upholstered furniture by weak heat sources (e.g., a cigarette, a short-circuited wire) and the persistent combustion of biomass behind the flaming fronts of wildfires.

Rapid

Rapid combustion is a form of combustion, otherwise known as a fire, in which large amounts of heat and light energy are released, which often results in a flame. This is used in a form of machinery such as internal combustion engines and in thermobaric weapons. Such a combustion is frequently called an explosion, though for an internal combustion engine this is inaccurate. An internal combustion engine nominally operates on a controlled rapid burn. When the fuel-air mixture in an internal combustion engine explodes, that is known as detonation.

Spontaneous

Spontaneous combustion is a type of combustion which occurs by self heating (increase in temperature due to exothermic internal reactions), followed by thermal runaway (self heating which rapidly accelerates to high temperatures) and finally, ignition.

Turbulent

Combustion resulting in a turbulent flame is the most used for industrial application (e.g. gas turbines, gasoline engines, etc.) because the turbulence helps the mixing process between the fuel and oxidizer.

Microgravity

Combustion processes behave differently in a microgravity environment than in Earth-gravity conditions due to the lack of buoyancy. For example, a candle's flame takes the shape of a sphere.[4] Microgravity combustion research contributes to understanding of spacecraft fire safety and diverse aspects of combustion physics.

Micro-combustion

Combustion processes which happen in very small volumes are considered micro-combustion. The high surface-to-volume ratio increases specific heat loss. Quenching distance plays a vital role in stabilizing the flame in such combustion chambers.

Chemical equations

Stoichiometric combustion of a hydrocarbon in oxygen

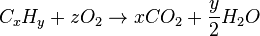

Generally, the chemical equation for stoichiometric combustion of a hydrocarbon in oxygen is:

where z = x + ¼y.

For example, the stoichiometric burning of propane in oxygen is:

The simple word equation for the stoichiometric combustion of a hydrocarbon in oxygen is:

Stoichiometric combustion of a hydrocarbon in air

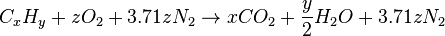

If the stoichiometric combustion takes place using air as the oxygen source, the nitrogen present in the air can be added to the equation (although it does not react) to show the composition of the resultant flue gas:

where z = x + ¼y.

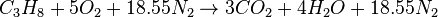

For example, the stoichiometric combustion of propane in air is:

The simple word equation for the stoichiometric combustion of a hydrocarbon in air is:

Trace combustion products

Various other substances begin to appear in significant amounts in combustion products when the flame temperature is above about 1,600 K. When excess air is used, nitrogen may oxidize to NO and, to a much lesser extent, to NO

2. CO forms by disproportionation of CO

2, and H

2 and OH form by disproportionation of H

2O.

For example, when 1 mol of propane is burned with 28.6 mol of air (120% of the stoichiometric amount), the combustion products contain 3.3% O

2. At 1,400 K, the equilibrium combustion products contain 0.03% NO and 0.002% OH. At 1,800 K, the combustion products contain 0.17% NO, 0.05% OH, 0.01% CO, and 0.004% H

2.[5]

Diesel engines are run with an excess of oxygen to combust small particles that tend to form with only a stoichiometric amount of oxygen, necessarily producing nitrogen oxide emissions. Both the United States and European Union enforce limits to vehicle nitrogen oxide emissions, which necessitate the use of special catalytic converters or treatment of the exhaust with urea (see Diesel exhaust fluid).

Incomplete combustion of a hydrocarbon in oxygen

The incomplete (partial) combustion of a hydrocarbon with oxygen produces a gas mixture containing mainly CO

2, CO, H

2O, and H

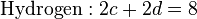

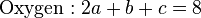

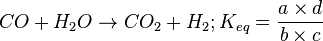

2. Such gas mixtures are commonly prepared for use as protective atmospheres for the heat-treatment of metals and for gas carburizing.[6] The general reaction equation for incomplete combustion of one mole of a hydrocarbon in oxygen is:

The simple word equation for the incomplete combustion of a hydrocarbon in oxygen is:

For stoichiometric (complete) combustion, z = x + ¼y. When z falls below roughly 50% of the stoichiometric value, CH

4 can become an important combustion product; when z falls below roughly 35% of the stoichiometric value, elemental carbon may become stable.

The products of incomplete combustion can be calculated with the aid of a material balance, together with the assumption that the combustion products reach equilibrium.[7][8] For example, in the combustion of one mole of propane (C

3H

8) with four moles of O

2, seven moles of combustion gas are formed, and z is 80% of the stoichiometric value. The three elemental balance equations are:

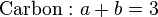

These three equations are insufficient in themselves to calculate the combustion gas composition. However, at the equilibrium position, the water gas shift reaction gives another equation:

For example, at 1,200 K the value of Keq is 0.728.[2] Solving, the combustion gas consists of 42.4% H

2O, 29.0% CO

2, 14.7% H

2, and 13.9% CO. Carbon becomes a stable phase at 1,200 K and 1 atm pressure when z is less than 30% of the stoichiometric value, at which point the combustion products contain more than 98% H

2 and CO and about 0.5% CH

4.

Fuels

Substances or materials which undergo combustion are called fuels. The most common examples are natural gas, propane, kerosene, diesel, petrol, charcoal, coal, wood, etc.

A good fuel is one which is readily available, is cheap, burns easily in air and at a moderate rate, has a high calorific value and is environment friendly. There is probably no fuel which can be considered an ideal fuel, but natural gas (mostly methane) comes the closest[citation needed].

Liquid fuels

Combustion of a liquid fuel in an oxidizing atmosphere actually happens in the gas phase. It is the vapor that burns, not the liquid. Therefore, a liquid will normally catch fire only above a certain temperature: its flash point. The flash point of a liquid fuel is the lowest temperature at which it can form an ignitable mix with air. It is also the minimum temperature at which there is enough evaporated fuel in the air to start combustion.

Solid fuels

The act of combustion consists of three relatively distinct but overlapping phases:

- Preheating phase, when the unburned fuel is heated up to its flash point and then fire point. Flammable gases start being evolved in a process similar to dry distillation.

- Distillation phase or gaseous phase, when the mix of evolved flammable gases with oxygen is ignited. Energy is produced in the form of heat and light. Flames are often visible. Heat transfer from the combustion to the solid maintains the evolution of flammable vapours.

- Charcoal phase or solid phase, when the output of flammable gases from the material is too low for persistent presence of flame and the charred fuel does not burn rapidly and just glows and later only smoulders.

Combustion management

Efficient process heating requires recovery of the largest possible part of a fuel’s heat of combustion into the material being processed.[9][10] There are many avenues of loss in the operation of a heating process. Typically, the dominant loss is sensible heat leaving with the offgas (i.e., the flue gas). The temperature and quantity of offgas indicates its heat content (enthalpy), so keeping its quantity low minimizes heat loss.

In a perfect furnace, the combustion air flow would be matched to the fuel flow to give each fuel molecule the exact amount of oxygen needed to cause complete combustion. However, in the real world, combustion does not proceed in a perfect manner. Unburned fuel (usually CO and H

2) discharged from the system represents a heating value loss (as well as a safety hazard). Since combustibles are undesirable in the offgas, while the presence of unreacted oxygen there presents minimal safety and environmental concerns, the first principle of combustion management is to provide more oxygen than is theoretically needed to ensure that all the fuel burns. For methane (CH

4) combustion, for example, slightly more than two molecules of oxygen are required.

The second principle of combustion management, however, is to not use too much oxygen. The correct amount of oxygen requires three types of measurement: first, active control of air and fuel flow; second, offgas oxygen measurement; and third, measurement of offgas combustibles. For each heating process there exists an optimum condition of minimal offgas heat loss with acceptable levels of combustibles concentration. Minimizing excess oxygen pays an additional benefit: for a given offgas temperature, the NOx level is lowest when excess oxygen is kept lowest.[3]

Adherence to these two principles is furthered by making material and heat balances on the combustion process.[11][12][13][14] The material balance directly relates the air/fuel ratio to the percentage of O

2 in the combustion gas. The heat balance relates the heat available for the charge to the overall net heat produced by fuel combustion.[15][16] Additional material and heat balances can be made to quantify the thermal advantage from preheating the combustion air,[17][18] or enriching it in oxygen.[19][20]

Reaction mechanism

Combustion in oxygen is a chain reaction in which many distinct radical intermediates participate. The high energy required for initiation is explained by the unusual structure of the dioxygen molecule. The lowest-energy configuration of the dioxygen molecule is a stable, relatively unreactive diradical in a triplet spin state. Bonding can be described with three bonding electron pairs and two antibonding electrons, whose spins are aligned, such that the molecule has nonzero total angular momentum. Most fuels, on the other hand, are in a singlet state, with paired spins and zero total angular momentum. Interaction between the two is quantum mechanically a "forbidden transition", i.e. possible with a very low probability. To initiate combustion, energy is required to force dioxygen into a spin-paired state, or singlet oxygen. This intermediate is extremely reactive. The energy is supplied as heat, and the reaction then produces additional heat, which allows it to continue.

Combustion of hydrocarbons is thought to be initiated by hydrogen atom abstraction (not proton abstraction) from the fuel to oxygen, to give a hydroperoxide radical (HOO). This reacts further to give hydroperoxides, which break up to give hydroxyl radicals. There are a great variety of these processes that produce fuel radicals and oxidizing radicals. Oxidizing species include singlet oxygen, hydroxyl, monatomic oxygen, and hydroperoxyl. Such intermediates are short-lived and cannot be isolated. However, non-radical intermediates are stable and are produced in incomplete combustion. An example is acetaldehyde produced in the combustion of ethanol. An intermediate in the combustion of carbon and hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, is of special importance because it is a poisonous gas, but also economically useful for the production of syngas.

Solid and heavy liquid fuels also undergo a great number of pyrolysis reactions that give more easily oxidized, gaseous fuels. These reactions are endothermic and require constant energy input from the ongoing combustion reactions. A lack of oxygen or other poorly designed conditions result in these noxious and carcinogenic pyrolysis products being emitted as thick, black smoke.

The rate of combustion is the amount of a material that undergoes combustion over a period of time. It can be expressed in grams per second (g/s) or kilograms per second (kg/s).

Temperature

Assuming perfect combustion conditions, such as complete combustion under adiabatic conditions (i.e., no heat loss or gain), the adiabatic combustion temperature can be determined. The formula that yields this temperature is based on the first law of thermodynamics and takes note of the fact that the heat of combustion is used entirely for heating the fuel, the combustion air or oxygen, and the combustion product gases (commonly referred to as the flue gas).

In the case of fossil fuels burnt in air, the combustion temperature depends on all of the following:

- the heating value;

- the stoichiometric air to fuel ratio

;

; - the specific heat capacity of fuel and air;

- the air and fuel inlet temperatures.

The adiabatic combustion temperature (also known as the adiabatic flame temperature) increases for higher heating values and inlet air and fuel temperatures and for stoichiometric air ratios approaching one.

Most commonly, the adiabatic combustion temperatures for coals are around 2,200 °C (3,992 °F) (for inlet air and fuel at ambient temperatures and for  ), around 2,150 °C (3,902 °F) for oil and 2,000 °C (3,632 °F) for natural gas.[21][22]

), around 2,150 °C (3,902 °F) for oil and 2,000 °C (3,632 °F) for natural gas.[21][22]

In industrial fired heaters, power station steam generators, and large gas-fired turbines, the more common way of expressing the usage of more than the stoichiometric combustion air is percent excess combustion air. For example, excess combustion air of 15 percent means that 15 percent more than the required stoichiometric air is being used.

Instabilities

Combustion instabilities are typically violent pressure oscillations in a combustion chamber. These pressure oscillations can be as high as 180 dB, and long term exposure to these cyclic pressure and thermal loads reduces the life of engine components. In rockets, such as the F1 used in the Saturn V program, instabilities led to massive damage of the combustion chamber and surrounding components. This problem was solved by re-designing the fuel injector. In liquid jet engines the droplet size and distribution can be used to attenuate the instabilities. Combustion instabilities are a major concern in ground-based gas turbine engines because of NOx emissions. The tendency is to run lean, an equivalence ratio less than 1, to reduce the combustion temperature and thus reduce the NOx emissions; however, running the combustion lean makes it very susceptible to combustion instability.

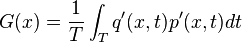

The Rayleigh Criterion is the basis for analysis of thermoacoustic combustion instability and is evaluated using the Rayleigh Index over one cycle of instability[23]

where q' is the heat release rate perturbation and p' is the pressure fluctuation.[24][25] When the heat release oscillations are in phase with the pressure oscillations, the Rayleigh Index is positive and the magnitude of the thermo acoustic instability is maximised. On the other hand, if the Rayleigh Index is negative, then thermoacoustic damping occurs. The Rayleigh Criterion implies that a thermoacoustic instability can be optimally controlled by having heat release oscillations 180 degrees out of phase with pressure oscillations at the same frequency.[26][27] This minimizes the Rayleigh Index.

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ colloquial meaning of burning is combustion accompanied by flames

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Reaction-Web

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The formation of NOx. Alentecinc.com. Retrieved on 2010-09-28.

- ↑ Shuttle-Mir History/Science/Microgravity/Candle Flame in Microgravity (CFM) – MGBX. Spaceflight.nasa.gov (1999-07-16). Retrieved on 2010-09-28.

- ↑ Equilib-Web

- ↑ ASM Committee on Furnace Atmospheres, Furnace atmospheres and carbon control, Metals Park, OH [1964].

- ↑ "Exothermic atmospheres". Industrial Heating: 22. June 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ ExoCalc

- ↑ "Calculating the heat of combustion for natural gas". Industrial Heating: 28. September 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ HeatCalc

- ↑ "Making a material balance". Industrial Heating: 20. November 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ MatBalCalc

- ↑ "Making a heat balance". Industrial Heating: 22. December 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ HeatBalCalc

- ↑ "Available combustion heat". Industrial Heating: 22. April 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ AvailHeatCalc

- ↑ "Making a system balance (Part 2)". Industrial Heating: 24. March 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ SysBalCalc2

- ↑ "Making a system balance (Part 1)". Industrial Heating: 22. February 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ SysBalCalc

- ↑ "Adiabatic flame temperature". Industrial Heating: 20. May 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ AFTCalc

- ↑ John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, Sc.D., F.R.S., Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge; "The Theory of Sound", §322h, 1878:

- ↑ A. A. Putnam and W. C. Dennis (1953) "Organ-pipe oscillations in a flame-filled tube," Fourth Symposium (International) on Combustion, The Combustion Institute, pp. 566–574.

- ↑ E. C. Fernandes and M. V. Heitor, “Unsteady flames and the Rayleigh criterion” in F. Culick, M. V. Heitor, and J. H. Whitelaw, ed.s, Unsteady Combustion (Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996), p. 4

- ↑ Dowling, A. P. (2000a). "Vortices, sound and flame – a damaging combination". The Aeronautical Journal of the RaeS

- ↑ Chrystie, Robin S. M.; Burns, Iain S.; Kaminski, Clemens F. (2013). "Temperature Response of an Acoustically Forced Turbulent Lean Premixed Flame: A Quantitative Experimental Determination". Combustion Science and Technology 185: 180. doi:10.1080/00102202.2012.714020.

Further reading

| Look up combustion in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Poinsot, Thierry; Veynante, Denis (2012). Theoretical and Numerical Combustion (3rd ed.). European Centre for Research and Advanced Training in Scientific Computation.

- Lackner, Maximilian; Winter, Franz; Agarwal, Avinash K., eds. (2010). Handbook of Combustion, 5 volume set. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-32449-1.

- Baukal, Charles E., ed. (1998). Oxygen-Enhanced Combustion. CRC Press.

- Glassman, Irvin; Yetter, Richard. Combustion (Fourth ed.).

- Turns, Stephen (2011). An Introduction to Combustion: Concepts and Applications.

- Ragland, Kenneth W; Bryden, Kenneth M. (2011). Combustion Engineering (Second ed.).

- Baukal, Charles E. Jr, ed. (2013). "Industrial Combustion". The John Zink Hamworthy Combustion Handbook: Three-Volume Set (Second ed.).

- Gardiner, W. C. Jr (2000). Gas-Phase Combustion Chemistry (Revised ed.).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||