Colard Mansion

Colard Mansion (or Colart, before 1440 – after May 1484) was a 15th-century Flemish scribe and printer who worked together with William Caxton. He is known as the first printer of a book with copper engravings, and as the printer of the first books in English and French.

Biography

Colard Mansion was a central figure in the early printing industry in Bruges. He was active as early as 1454 as a bookseller, and was also active as a scribe, translator and contractor for manuscripts, which meant entering into contracts with the clients, and organizing and sub-contracting the elements such as scribing, decorating and binding.[1] From 1474 until 1476 he worked together with the early English printer William Caxton, and he continued the company on his own afterwards. Caxton probably learned the art of printing from Mansion,[2] and it was from Mansion's press that the first books printed in English (Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye) and French came.[3] He moved to the Burg, the commercial heart of Bruges at the time, in 1478. Mansion suffered heavily under the economic crisis in Bruges in the 1480s, and only one work was printed after the death of Mary of Burgundy in 1482. Nothing is known with certainty about his life after 1484, although he may have moved to Picardy.

Work

Mansion sold illuminated manuscripts to the aristocracy, and luxurious incunabula to the bourgeoisie, but he was one of the first to also publish smaller and cheaper books of only twenty to thirty pages, mainly in French. Nowadays, 25 editions of incunabula by Mansion alone are known, making him the most prolific of Bruges' early printers. Only two of these are in Latin, all others are in French, many of them first editions. Customers of Mansion include Charles de Croÿ, prince of Chimay, and Marie, the widow of Louis de Luxembourg, Count of Saint-Pol. Mansion has been called the first printer of luxury books.[4]

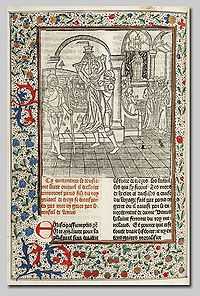

He collaborated with major manuscript illuminators, such as the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book, who were fast losing work to printing, or copyists of their work. In fact only two of his books are illustrated, the influential Ovide Moralisé with woodcuts, and a French translation of Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium, the first book to be illustrated with engravings, some of which have been claimed to be the work of the Dresden Prayer Book Master and other identified illuminators in the circle of the Master of Anthony of Burgundy. As intaglio prints, the nine engravings had to be printed separately from the relief text and then pasted in, and only three copies are known with the engravings. More copies are known without the engravings, several of which contain illuminations instead. It has been suggested that this was Mansion's original intention (other incunabula left spaces for manual illustration), but that this hybrid product did not attract the wealthy buyers of illuminations, so the engravings were an afterthought, aimed at a less exclusive market.[5] Mansion is also known as the translator of at least five texts from Latin to French, including Le dialogue des créatures, printed by Dutch Gerard Leeu in 1482.

Known works

- 1467: Romuleon (manuscript by Benvenuto Rambaldi da Imola, translated by Jean Miélot, dedicated to Philip the Good[6]

- 1472 or later: Penitence d'Adam (Testament of Adam) (manuscript), dedicated to Lewis de Bruges[6]

- 1474-1475: Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, together with William Caxton and Johann Veldener

- 1475: The Game and Playe of Chesse, together with Caxton (who translated it from the French version), based on a work by Jacobus de Cessolis

- 1476: Le Jardin de dévotion by Petrus de Alliaco, Mansion's first book as an independent publisher

- 1476: De la ruine des nobles hommes et femmes (De Casibus Virorum Illustrium) by Giovanni Boccaccio, translated into French by Laurent Premierfait, was the first book to be illustrated with engravings,[7] probably made by Marc le Bongeteur.

- 1476: Controversie de Noblesse by Buonaccorso da Montemagno (or Surse de Pistoye), translated into French by Jean Miélot

- 1476-1477: an anonymous French prediction text

- 1477: La consolation de la philosophie by Boethius

- 1477: Estrif de Fortune et de Vertu (anonymous)[6]

- 1477: Traité de l’espere, French translation of the Tractatus de Origine, Natura, Jure et Mutationibus Monetarum by Nicole Oresme in 26 chapters[8]

- 1479: Le quadriloque invectif by Alain Chartier

- 1479: La somme rurale by Jean Boutillier

- 1479: Opera : De caelesti hyerarchia. De ecclesiastica hyerarchia. De divinis nominibus. De mystica theologia. Epistolae, a complete edition in Latin of the works of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, translated by Ambrosio Traversari

- 1480: Art de bien mourir (anonymous)

- 1480?: Guillaume Caoursin, Rhodiae Obsidionis descriptio[9]

- before June 1481: Valere Maxime (life of Saint Hubert), dedicated to Philippe de Hornes[6]

- 1482: Dyalogue des creatures, translated by Mansion from the Latin Dialogus creaturarum[6]

- 1484: Ovide moralisé, first edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses, illustrated with woodcuts, rearranged and partly rewritten by Mansion himself, published in May 1484.[10] It is his last known work, and it has been speculated that the expensive book bankrupted the company. This book was reprinted as the Bible des poëtes (Poets' Bible) at least four times in Paris between 1493 and 1531. Afterwards, a purer version (with all allegorical additions by Mansion removed, but keeping his translations) under the title Grand Olympe des histoires poëtiques du Prince de poësie Ovide Naso en sa Metamorphose was published repeatedly between 1532 and 1570.

- Unknown date:

- the Distichs of Cato

- Les Evangiles des quenouilles (anonymous, circa 1480)

- La doctrine de bien vivre en ce monde (also called Donat espirituel) by Jean Gerson

- La Danse des aveugles by Pierre Michault, secretary of Charles the Bold

- Invectives contre la secte de Vauderie

- Adevineaux amoureux (anonymous).[6]

Incunabula by Mansion are scattered throughout collections mainly in Western Europe. The largest such collection is in Paris, and the 16 copies of 10 different titles in the Public Library of Bruges form the second biggest collection.[11]

Notes

- ↑ Such a contract is described on p. 59 of T Kren & S McKendrick (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7

- ↑ British History Online

- ↑ The Story of Books by Gertrude Burford Rawlings, 1901

- ↑ Drukkunst bezorgde Brugge internationale faam Het Nieuwsblad, 2004-12-21.

- ↑ Copies with engravings are in Amiens, Boston MFA & Getty private Collection, England. T Kren & S McKendrick (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, pp. 271-4, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7, see also An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, Arthur M. Hind,p. 592, Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Arlima, archives du littérature du moyen-age

- ↑ Musée des arts et métiers exposition on early printed books

- ↑ André Lapidus 1998

- ↑ Kelly, William A. (2007). Low Countries imprints in Scottish research libraries. Waxmann Verlag. p. 157. ISBN 978-3-8309-1866-0. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ↑ Historische Bronnen Brugge

- ↑ Mansion collection of the Bruges library

Sources

- T Kren & S McKendrick (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7

- Biography at Historische Bronnen Brugge Last accessed at September 27, 2007

- Short biography in English at the Dutch Royal Library Last accessed at September 27, 2007

- Carton, Charles Louis (1848). Colard Mansion et les imprimeurs brugeois du 15me siècle (in French). Vande Casteele-Werbroeck. p. 44. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

|