Coast Salish art

Coast Salish art is an art unique to the Pacific Northwest Coast among the Coast Salish peoples. Coast Salish are peoples from the Pacific Northwest Coast made up of many different languages and cultural characteristics. Coast Salish territory covers the coast of British Columbia and Washington state. Within traditional Coast Salish art there are two major forms; the flat design and carving, and basketry and weaving. In historical times these were delineated among male and female roles in the community with men made "figurative pieces, such as sculptures and paintings that depicts crest, shamanic beings, and spirits, whereas women produced baskets and textiles, most often decorated with abstract designs."[1]

History

The settlement of non-natives in this region was one of the first for the Pacific Northwest Coast which brought early cultural disruptions much sooner and faster than most of the coast.This made it so a limited quantity of ancient artifacts of the art form were produced, especially compared to amount that exists about other Northwest Coastal art.[2]

The Coast Salish lived in shed-roofed longhouses, large dwellings made from cedar planks and beams, with large extended families living within the house. Platforms around on the inside stood 3 or 4 feet above ground against the wall and were used as sleeping area's. Sometimes large beams on the sides of the longhouse called "House Posts" would be carved or painted depicting ancestors, family history, or supernatural beings. Some longhouses grew to enormous sizes such as one Simon Fraser described in his visit with Sto:lo people with a house measuring 640 feet long and 60 feet wide[3] or another Sḵwx̱wú7mesh longhouse measuring 200 feet long by 60 feet wide where 11 families lived in the house, numbering around 100 people.[4]

Among Coast Salish in the central region, the sxwayxwey (Sx̱wáýx̱way or Skwayskway in other languages) mask ceremony is an important part of the culture. [5] Men from families who have the hereditary right to be initiated into the sxwayxwey society and wear the mask, and perform dance with the addition of women singers and a special song. The masks themselves have budged out cylindrical eyeballs, “horns” represented by animal heads, and drooping tongues with large feathers creating a dynamic crown. They are accompanied by special regalia covered with feathers and leggings with hoof rattles attached.

House posts, grave monuments, masks, ritual paraphernalia such as rattles, and women crafted woven robes, some plain, some elaborately coloured. Rattles made from sheets of mountain-goat horn bent and then sewn to form volumetric triangles originally adorned with strands of mountain-goat wool.

The art form is used in spindle whorls, house posts, welcome figures, combs, bent wood boxes, canoes, and other cultural objects.

Revival

Coast Salish art has undergone a revival in recent years.[7][8] One person involved in the revival is Sḵwx̱wú7mesh artist Aaron Nelson-Moody. In 2005 he carved a large cedar door to be used at the BC-Canada Pavilion in the 2006 Turin Olympic Game.[9][10]

Cowichan artist Edward Joe, who has adapted the Coast Salish art form into fine jewelry and prints, says "(Coast) Salish art has as smooth slowing motion intended to create a calm mood. The stories, legends, and myths are depicted in many of my art pieces. Animals from the land, sea, and sky are designed in a playful manner."[11]

On October 24, 2008, the Seattle Art Museum opened "S'abadeb—The Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists", a Coast Salish art exhibition from 75 works of art from national and international collections of both traditional and contemporary artists.[12]

Characteristics

It also differs from other Northwest Coast art in that it is more minimalist and straight forward. A belief in the overexposure of spirit images would weaken the spiritual powers of the beings portrayed, and as a result very few pieces were produced.[13]

The "simplicity, antiquity, limited quantity and sometimes impenetrable iconography of (Coast) Salish art" have led to dismiss it in comparison to neighbor art forms, but Aldona Jonaitis in Art of the Northwest Coast remarks "Coast Salish art, like that of other Northwest Coast groups, responds to the social needs for which the archaic style was well suited... Coast Salish art cannot be judged according to alien values appropriate to other Northwest Coast groups, but, like most kinds of art, must be understood as visual statements meaningful and valuable to their creators."[14]

Coast Salish artists

Gallery

-

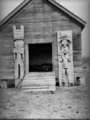

Musqueam people with house post in background. -

Musqueam house posts. -

Musqueam house post. -

Salish cloak, late 1700s.

See also

References

- ↑ Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0. p22

- ↑ Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0. p 87-88

- ↑ Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0. p71

- ↑ Barman, Jean. Stanley Park's Secret. Harbour Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1-55017-420-5. p 46.

- ↑ Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0. p 75

- ↑ Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0. p 85

- ↑ Laurence, Robin. Susan Point's huge Coast Salish portals pay rich tribute. - Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ↑ Darrell, Johnny. New Stanley Park Gateways "People Amongst the People". - Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ↑ Lee, Jeff. Turin exposure sparked lots of interest in carver. - Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ↑ Photo gallery of carved doors by Aaron Nelson-Moody. - Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ↑ Edward Joe Profile at Alcheringa Gallery. - Retrieved November 9, 2008

- ↑ S'abadeb—The Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists - Retrieved November 09, 2008.

- ↑ Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0. p 87-88

- ↑ Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0. p 88

- ↑ Sinoski, Kelly (20 October 2007). "Salish artist designs $1,600 gold coin". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Fraughton, Holly (12 March 2010). "Nelson Moody carving out a niche". Pique Newsmagazine. Archived from the original on 16 August 2013.

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul Robert (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. University of Toronto Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780802029386. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

Further reading

- Steven C. Brown, Rebecca Blanchard, and Nancy Davenport. Contemporary Coast Salish Art. University of Washington Press (August 2005). ISBN 978-0-295-98485-8.

- Point, Susan. Susan Point: Coast Salish artist. Douglas & McIntyre (November 2000). ISBN 978-0-295-98018-8.

- Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre, 2006. ISBN 0-295-98636-0.

External links

- Seattle Art Museum: "S'abadeb—The Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists" — Coast Salish art show.

- RRN: Coast Salish art

- U.Wash Digital Collections: Photo of Lummi carver Al Charles (1970)

- UVic anthropologist “transports” Coast Salish art to the public

- Coast Salish Welcome Figures at YVR Airport

_-_DSC04958.JPG)