Classical electron radius

The classical electron radius, also known as the Lorentz radius or the Thomson scattering length, is based on a classical (i.e., non-quantum) relativistic model of the electron. According to modern research, the electron is assumed to be a point particle with a point charge and no spatial extent.[1] However, the classical electron radius is calculated as

where  and

and  are the electric charge and the mass of the electron,

are the electric charge and the mass of the electron,  is the speed of light, and

is the speed of light, and  is the permittivity of free space.[2]

is the permittivity of free space.[2]

In cgs units, this becomes more simply

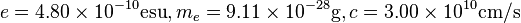

with (to three significant digits)

.

.

Using classical electrostatics, the energy required to assemble a sphere of constant charge density, of radius  and charge

and charge  is

is

.

.

If the charge is on the surface the energy is

.

.

Ignoring the factors 3/5 or 1/2, if this is equated to the relativistic energy of the electron ( ) and solved for

) and solved for  , the above result is obtained.

, the above result is obtained.

In simple terms, the classical electron radius is roughly the size the electron would need to have for its mass to be completely due to its electrostatic potential energy - not taking quantum mechanics into account. We now know that quantum mechanics, indeed quantum field theory, is needed to understand the behavior of electrons at such short distance scales, thus the classical electron radius is no longer regarded as the actual size of an electron. Still, the classical electron radius is used in modern classical-limit theories involving the electron, such as non-relativistic Thomson scattering and the relativistic Klein-Nishina formula. Also, the classical electron radius is roughly the length scale at which renormalization becomes important in quantum electrodynamics.

The classical electron radius is one of a trio of related units of length, the other two being the Bohr radius  and the Compton wavelength of the electron

and the Compton wavelength of the electron  . The classical electron radius is built from the electron mass

. The classical electron radius is built from the electron mass  , the speed of light

, the speed of light  and the electron charge

and the electron charge  . The Bohr radius is built from

. The Bohr radius is built from  ,

,

and Planck's constant

and Planck's constant  . The Compton wavelength is built from

. The Compton wavelength is built from  ,

,  and

and  . Any one of these three lengths can be written in terms of any other using the fine structure constant

. Any one of these three lengths can be written in terms of any other using the fine structure constant  :

:

Extrapolating from the initial equation, any mass  can be imagined to have an 'electromagnetic radius' similar to the electron's classical radius.

can be imagined to have an 'electromagnetic radius' similar to the electron's classical radius.

where  is Coulomb's constant,

is Coulomb's constant,  is the fine structure constant and

is the fine structure constant and  is the reduced Planck's constant.

is the reduced Planck's constant.

References

- ↑ Curtis, L.J. (2003). Atomic Structure and Lifetimes: A Conceptual Approach. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-521-53635-9.

- ↑ David J. Griffiths, Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, Prentice-Hall, 1995, p. 155. ISBN 0-13-124405-1

- CODATA value for the classical electron radius at NIST.

- Arthur N. Cox, Ed. "Allen's Astrophysical Quantities", 4th Ed, Springer, 1999.

External links

- Length Scales in Physics: the Classical Electron Radius

- Structure and radius of electron, an intuitive explanation