Clarithromycin

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

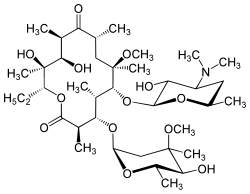

| (3R,4S,5S,6R,7R,9R,11S,12R,13S,14S)-6-{[(2S,3R,4S,6R) -4-(dimethylamino)-3-hydroxy-6-methyloxan-2-yl]oxy} -14-ethyl-12,13-dihydroxy-4-{[(2R,4S,5S,6S)-5-hydroxy -4-methoxy-4,6-dimethyloxan-2-yl]oxy}-7 -methoxy-3,5,7,9,11,13-hexamethyl -1-oxacyclotetradecane-2,10-dione | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Biaxin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a692005 |

| Pregnancy cat. | C (USA) B3 (Aus) |

| Legal status | prescription only |

| Routes | oral, intravenous |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% |

| Protein binding | low binding |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Half-life | 3-4 h |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 81103-11-9 |

| ATC code | J01FA09 |

| PubChem | CID 5284534 |

| DrugBank | DB01211 |

| ChemSpider | 21112273 |

| UNII | H1250JIK0A |

| KEGG | D00276 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1741 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C38H69NO13 |

| Mol. mass | 747.953 g/mol |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Clarithromycin (6-O-methyl erythromycin) is a macrolide antibiotic used to treat pharyngitis, tonsillitis, acute maxillary sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, pneumonia (especially atypical pneumonias associated with Chlamydophila pneumoniae), skin and skin structure infections. In addition, it is sometimes used to treat legionellosis, Helicobacter pylori, and lyme disease. Recently there has been research towards whether Clarithromycin can be used to effectively treat idiopathic hypersomnia.[1]

Clarithromycin is available under several brand names, for example Bioclar, Truclar, Crixan, Claritt, Clarac, Biaxin, Klaricid, Klacid, Klaram, Klabax, Claripen, Clarem, Claridar, Fromilid, Clacid, Clacee, Vikrol, Infex, Clariwin, Resclar, Ranbaxy and Clarihexal,Clarinova 250mg & 500mg, Monoclar (by Bosnalijek)...

History

Clarithromycin was invented by researchers at the Japanese drug company Taisho Pharmaceutical in the 1970s. The product emerged through efforts to develop a version of the antibiotic erythromycin that did not experience acid instability in the digestive tract, causing side effects, such as nausea and stomach ache. Taisho filed for patent protection for the drug around 1980 and subsequently introduced a branded version of its drug, called Clarith, to the Japanese market in 1991. In 1985, Taisho partnered with the American company Abbott Laboratories for the international rights, and Abbott also gained FDA approval for Biaxin in October 1991. The drug went generic in Europe in 2004 and in the US in mid-2005.

Its antibacterial spectrum is the same as erythromycin, but it is also active against Mycobacterium avium complex MAV, M. leprae and atypical mycobacteria.

Mechanism of action

Clarithromycin prevents bacteria from growing by interfering with their protein synthesis. It binds to the subunit 50S of the bacterial ribosome and thus inhibits the translation of peptides. Clarithromycin has similar antimicrobial spectrum as erythromycin, but is more effective against certain Gram-negative bacteria, particularly Legionella pneumophila. Besides this bacteriostatic effect, clarithromycin also has bactericidal effect on certain strains, such as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Pharmacokinetics

Unlike erythromycin, clarithromycin is acid-stable, so can be taken orally without being protected from gastric acids. It is readily absorbed, and diffused into most tissues and phagocytes. Due to the high concentration in phagocytes, clarithromycin is actively transported to the site of infection. During active phagocytosis, large concentrations of clarithromycin are released; its concentration in the tissues can be over 10 times higher than in plasma. Highest concentrations were found in liver, lung tissue and stool.

Metabolism

Clarithromycin has a fairly rapid first-pass hepatic metabolism in human liver. Its major metabolites include N-desmethylclarithromycin and 14-(R)-hydroxyclarithromycin. 14-(R)-hydroxy clarithromycin is an active metabolite. Compared to clarithromycin, it is less potent against Mycobacterial tuberculosis and Mycobacterial avium complex. Its MIC against Mycobacterial tuberculosis H37RV luxABCDE strain is 35 μM. Besides these two major metabolites, clarithromycin is also metabolized to 14-(S)-hydroxy clarithromycin. However, N-desmethylclarithromycin and 14-(S)-hydroxy clarithromycin are inactive metabolites. Clarithromycin (20%-40%) and its active metabolite (10%-15%) are found in urine. Of all the drugs in its class, clarithromycin has the best bioavailability at 50%, which makes it amenable to oral administration.

Side effects

Its most common side effects are gastrointestinal: diarrhea, Drowsiness, nausea, abdominal pain and vomiting, facial swelling. Less common side effects include extreme irritability, headaches, hallucinations (auditory and visual), dizziness/motion sickness, rashes, alteration in senses of smell and taste, including a metallic taste that lasts the entire time one takes it. Dry mouth, panic and / or anxiety attacks and nightmares have also been reported, albeit less frequently. In more serious cases, it has been known to cause jaundice, cirrhosis, and kidney problems, including renal failure. Uneven heartbeats, chest pain, and shortness of breath have also been reported while taking this drug.

Clarithromycin causes positive results on urine drug screens for cocaine.[citation needed]

Adverse effects of clarithromycin in the central nervous system include dizziness, ototoxicity and headaches, but delirium and mania are also uncommon side effects. According to one study, its use has led to adverse effects on the nervous system in up to 3% of patients, including dizziness, anxiety, insomnia, bad dreams, confusion, disorientation and hallucination.[2] It can very rarely cause organic psychosis.[3]

When taken along with some statins used to reduce blood serum cholesterol levels, muscle pain may occur.

A risk of oral candidiasis, due to the elimination of the yeast's natural bacterial competitors by the antibiotic is also incurred.

Clarithromycin has been shown to induce miscarriage in several animals and a recent study found an increased risk of miscarriage in women exposed to Clarithromycin in early pregnancy.[4]

Spectrum of resistance and susceptibility

Many Gram-positive microbes quickly develop resistance to clarithromycin after standard courses of treatment, most frequently via acquisition of the erm(B) gene, which confers high-level resistance to all macrolides.[5] Clarithromycin has a broad spectrum of activity and has been effective in treating bacterial infections including tonsillitis, sinusitis, pneumonia, and others. The following represents susceptibility data for a few medically significant microorganisms.

- Haemophilus influenzae: 0.008 μg/mL - >256 μg/mL

- Streptococcus pneumoniae: 0.001 μg/mL - >256 μg/mL

- Streptococcus pyogenes: 0.001 μg/mL - >128 μg/mL

Contraindications

Clarithromycin should be used with caution if the patient has liver or kidney disease, certain heart problems or takes drugs that might cause certain heart problems (e.g., QT prolongation or bradycardia), or an electrolyte imbalance (e.g., low potassium or sodium levels). Many other drugs can interact with clarithromycin, so doctors should be informed of any other drugs taken concomitantly. Since clarithromycin inhibits Cytochrome P450 3A4(CYP3A4) enzyme which induces the metabolism of several drugs (notable example being calcium channel blockers like nifedipine), they should not be used together or it may result in hospitalizations with acute kidney damage or low blood pressure.

Clarithromycin is almost never used in HIV patients due to significant interaction with HIV drugs. It is not to be used in pregnant patients. It can also cause serotonin syndrome symptoms when taken in conjunction with buspirone (Buspar).

Clarithromycin almost doubles the level of carbamazepine in serum by reducing its clearance, inducing toxic symptoms of carbamazepine, including diplopia and nausea, as well as hyponatremia (reduced level of sodium in serum). Research in many cases has shown a sharp increase in serum level of carbamazepine in patients who were given clarithromycin. Therefore, epileptic patients taking carbamazepine should avoid taking clarithromycin.

Drugs using clarithromycin

In Pakistan it is available under the brand name Claritek™, and is manufactured and marketed by Getz Pharmaceuticals. Its use is approved for upper and lower RTI, H. pylori, and, skin and soft tissue infections. In Bangladesh, it is available as Claricin, produced by the Acme Laboratories Ltd. In the United States, generic clarithromycin is available from Andrx, Genpharm, Ivax, Ranbaxy Laboratories, Roxane, Sandoz, Teva and Wockhardt. It is also used as part of a combination therapy to treat Helicobacter pylori. In the Middle East, it is available as Claridar, produced by Dar Al Dawa. In India, Acnesol-CL gel, containing 1% clarithromycin, marketed by Systopic, is used to treat acne vulgaris.

Potential increased mortality

In the CLARICOR Trial, the use of short-term clarithromycin treatment correlated with an increased incidence of deaths classified as sudden cardiac deaths in stable coronary heart disease patients not using statins.[7] Clarithromycin can potentially cause long QT syndrome, especially in individuals with predispositions or taking medications that pose similar side effects, such as atypical antipsychotics. Some case reports suspect it of causing liver disease.[8]

References

- ↑ Lynn Marie Trotti, MD (June 15, 2010). "Clarithromycin for the Treatment of Primary Hypersomnia". Emory University - Georgia Research Alliance. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- ↑ http://pb.rcpsych.org/content/28/3/98.full

- ↑ Abba-Aji A & Mulligan O. Psychosis Beware! A Case Series of Clarithromycin and Psychosis – Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine – Jun.2007.Vol.24 no2. P 79-80.

- ↑ Andersen JT, Petersen M, Jimenez-Solem E, Broedbaek K, Andersen NL, et al. (2013) Clarithromycin in Early Pregnancy and the Risk of Miscarriage and Malformation: A Register Based Nationwide Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 8(1): e53327. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053327

- ↑ Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Lammens, C.; Coenen, S.; Van Herck, K.; Goossens, H. (2007). "Effect of azithromycin and clarithromycin therapy on pharyngeal carriage of macrolide-resistant streptococci in healthy volunteers: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". The Lancet 369 (9560): 482–490. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60235-9. PMID 17292768.

- ↑ http://www.toku-e.com/Assets/MIC/Clarithromycin%20USP.pdf

- ↑ Winkel, P.; Hilden, J. R.; Fischer Hansen, J. R.; Hildebrandt, P.; Kastrup, J.; Kolmos, H. J. R.; Kjøller, E.; Jespersen, C. M.; Gluud, C.; Jensen, G. B.; Claricor Trial, G. (2011). "Excess Sudden Cardiac Deaths after Short-Term Clarithromycin Administration in the CLARICOR Trial: Why is This So, and Why Are Statins Protective". Cardiology 118 (1): 63–67. doi:10.1159/000324533. PMID 21447948.

- ↑ Tietz, A.; Heim, M. H.; Eriksson, U.; Marsch, S.; Terracciano, L.; Krähenbühl, S. (2003). "Fulminant liver failure associated with clarithromycin". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 37 (1): 57–60. PMID 12503933.

External links

- "Biaxin XL (labeling)" (pdf). Abbott Laboratories.

- US patent 4331803, Watanabe, Y.; Morimoto, S. & Omura, S., "Novel erythromycin compounds", issued 1981-05-19, assigned to Taisho Pharmaceutical

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||