Halifax (former city)

| Halifax Jipugtug Chebucto Halafacs (Gaelic) | |

|---|---|

| Former City | |

| City of Halifax | |

| |

| |

Halifax | |

| Coordinates: 44°40′12″N 63°36′36″W / 44.67000°N 63.61000°WCoordinates: 44°40′12″N 63°36′36″W / 44.67000°N 63.61000°W | |

| Country |

|

| Province |

|

| Census metropolitan area | Halifax Regional Municipality |

| Founded | June 21, 1749 |

| Incorporated (City) | 1842 |

| Dissolved | April 1, 1996 |

| Area | |

| • Former City | 97.2 km2 (37.54 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 262.65 km2 (101.41 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 5,528.25 km2 (2,134.47 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0–119 m (0-390 ft) |

| Population (2011)[citation needed] | |

| • Former City | 130,130 |

| • Urban | 297,943 |

| • Metro | 413,700 |

| Time zone | AST (UTC-4) |

| • Summer (DST) | ADT (UTC-3) |

| Canadian Postal code | B3H to B3S |

| Area code(s) | 902 |

| Telephone Exchanges | 209 219 220 -3 225 229 233 237 240 244 266 268 292 333 334 344 377 400 -6 412 420 -9 430 -1 440 -6 448 449 450 -9 470 – 9 480 -4 486 – 9 490 -9 551 558 -9 720 -2 802 830 876 877 880 981 982 |

| GNBC Code | CAPHL |

| NTS Map | 011D12 |

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Halifax, Nova Scotia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Events | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The City of Halifax was an incorporated city in Nova Scotia, Canada, which was established as the Town of Halifax in 1749, and incorporated as a city in 1842. On April 1, 1996, the government of Nova Scotia dissolved the City of Halifax, and amalgamated the four municipalities within Halifax County and formed Halifax Regional Municipality, a single-tier regional government covering that whole area. The city was the capital of Nova Scotia and shire town of Halifax County. It was also the largest city in Atlantic Canada.[1]

The Town of Halifax was founded by British government under the direction of the Board of Trade and Plantations under the command of Governor Edward Cornwallis in 1749.[2] The British founding of Halifax initiated Father Le Loutre's War. During the war, Mi'kmaq and Acadians raided the capital region 13 times.

Halifax was founded below a glacial drumlin that would later be named Citadel Hill. The outpost was named in honour of George Montague-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax, who was the President of the British Board of Trade. Halifax was ideal for a military base, with the vast Halifax Harbour, among the largest natural harbours in the world, which could be well protected with batteries at McNab's Island, the North West Arm, Point Pleasant, George's Island and York Redoubt. In its early years, Citadel Hill was used as a command and observation post, before changes in artillery that could range out into the harbour.

After a protracted struggle between residents and the Governor, the City of Halifax was incorporated in 1842.

Since the creation of HRM in 1996, the area of the former City of Halifax is referred to as an unincorporated "provincial metropolitan area" by the provincial government's place name website[3] and the area is referred to as "Halifax, Nova Scotia" for civic addressing and as a placename.

The area is administered as two separate community planning areas by the regional government for development, Halifax Peninsula and Mainland Halifax. It forms a significant part of the Halifax urban area. Residents of the former city are called "Haligonians".

Town of Halifax

Historical context

The Mi'kmaq called the area "Jipugtug",[4][5] (anglicised as "Chebucto"), which means "the biggest harbour",[6][7][8] in reference to present-day Halifax Harbour. There is evidence that bands would spend the summer on the shores of the Bedford Basin, moving to points inland before the harsh Atlantic winter set in. Examples of Mikmaq habitation and burial sites have been found from Point Pleasant Park to the north and south mainland. Prior to the establishment of Halifax, the most remarkable event in the region was the fate of the Duc d'Anville Expedition.

Despite the Conquest of Acadia in 1710, no serious attempts were made by Great Britain to colonize Nova Scotia, aside from its presence at Annapolis Royal and Canso. The peninsula was dominated by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq residents. The British founded Halifax in order to counter the influence of the Fortress of Louisbourg [9] after returning the fortress to French control as part of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748).[10]

Father Le Loutre's War

The establishment of Halifax marked the beginning of Father Le Loutre's War. The war began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports and a sloop of war on June 21, 1749.[11] By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which were signed after Father Rale's War.[12] Cornwallis brought along 1,176 settlers and their families. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian, and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (Citadel Hill)(1749), Dartmouth (1750), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1751), Lunenburg (1753) and Lawrencetown (1754).

During Father Le Loutre's War, the Mi'kmaq and Acadians raided in the capital region (Halifax and Dartmouth) 12 times. The worst of these raids was the Dartmouth Massacre (1751). Four of these raids were against Halifax. The first of these was in July 1750: in the woods on peninsular Halifax, the Mi'kmaq scalped Cornwallis' gardener, his son, and four others. They buried the son, left the gardener's body exposed, and carried off the other four bodies.[13]

In 1751, there were two attacks on blockhouses surrounding Halifax. Mi'kmaq attacked the North Blockhouse (located at the north end of Joseph Howe Drive) and killed the men on guard. They also attacked near the South Blockhouse (located at the south end of Joseph Howe Drive), at a saw-mill on a stream flowing out of Chocolate Lake. They killed two men.[14] (Map of Halifax Blockhouses)

In 1753, when Lawrence became governor, the Mi'kmaq attacked again upon the sawmills near the South Blockhouse on the Northwest Arm, where they killed three British. The Mi'kmaq made three attempts to retrieve the bodies for their scalps.[15]

Prominent Halifax business person Michael Francklin was captured by a Mi'kmaw raiding party in 1754 and held captive for three months.[16]

French and Indian War

The town proved its worth as a military base in the French and Indian War (the North American Theatre of the Seven Years' War) as a counter to the French fortress Louisbourg in Cape Breton. Halifax provided the base for the Siege of Louisbourg (1758) and operated as a major naval base for the remainder of the war. On Georges Island (Nova Scotia) in the Halifax harbour, Acadians from the expulsion were imprisoned.

Acadian Pierre Gautier, son of Joseph-Nicolas Gautier, led Mi’kmaq warriors from Louisbourg on three raids against Halifax in 1757. In each raid, Gautier took prisoners or scalps or both. The last raid happened in September and Gautier went with four Mi’kmaq and killed and scalped two British men at the foot of Citadel Hill. (Pierre went on to participate in the Battle of Restigouche.)[17]

The Sambro Island Lighthouse was constructed at the harbour entrance in 1758 to develop the port city's merchant and naval shipping.[18] A permanent navy base, the Halifax Naval Yard was established in 1759. For much of this period in the early 18th century, Nova Scotia was considered a frontier posting for the British military, given the proximity to the border with French territory and potential for conflict; the local environment was also very inhospitable and many early settlers were ill-suited for the colony's wilderness on the shores of Halifax Harbour. The original settlers, who were often discharged soldiers and sailors, left the colony for established cities such as New York and Boston or the lush plantations of the Virginias and Carolinas. However, the new city did attract New England merchants exploiting the nearby fisheries and British merchants such as Joshua Maugher who profited greatly from both British military contracts and smuggling with the French at Louisbourg. The military threat to Nova Scotia was removed following British victory over France in the Seven Years' War.

With the addition of remaining territories of the colony of Acadia, the enlarged British colony of Nova Scotia was mostly depopulated, following the deportation of Acadian residents. In addition, Britain was unwilling to allow its residents to emigrate, this being at the dawn of their Industrial Revolution, thus Nova Scotia invited settlement by "foreign Protestants". The region, including its new capital of Halifax, saw a modest immigration boom comprising Germans, Dutch, New Englanders, residents of Martinique and many other areas. In addition to the surnames of many present-day residents of Halifax who are descended from these settlers, an enduring name in the city is the "Dutch Village Road", which led from the "Dutch Village", located in Fairview. Dutch here referring to the German "Deutsch" which sounded like "dutch" to Haligonian ears.

The American Revolution

Halifax's fortunes waxed and waned with the military needs of the Empire. While it had quickly become the largest Royal Navy base on the Atlantic coast and had hosted large numbers of British army regulars, the complete destruction of Louisbourg in 1760 removed the threat of French attack. With peace in 1763, the garrison and naval squadron was dramatically reduced. With naval vessels no longer carrying the mail, Halifax merchants banded together in 1765 to build the Nova Scotia Packet a schooner to carry mail to Boston, later commissioned as the naval schooner HMS Halifax, the first warship built in British Canada.[19] Meanwhile Boston and New England turned their eyes west, to the French territory now available due to the defeat of Montcalm at the Plains of Abraham. By the mid-1770s the town was feeling its first of many peacetime slumps.

The American Revolutionary War was not at first uppermost in the minds of most residents of Halifax. The government did not have enough money to pay for oil for the Sambro lighthouse. The militia was unable to maintain a guard, and was disbanded. Provisions were so scarce during the winter of 1775 that Quebec had to send flour to feed the town. While Halifax was remote from the troubles in the rest of the American colonies, martial law was declared in November 1775 to combat lawlessness.

On March 30, 1776, General William Howe arrived, having been driven from Boston by rebel forces. He brought with him 200 officers, 3000 men, and over 4,000 loyalist refugees, and demanded housing and provisions for all. This was merely the beginning of Halifax's role in the war. Throughout the conflict, and for a considerable time afterwards, thousands more refugees, often "in a destitute and helpless condition"[20] had arrived in Halifax or other ports in Nova Scotia. This would peak with the evacuation of New York, and continue until well after the formal conclusion of war in 1783. At the instigation of the newly arrived Loyalists who desired greater local control, Britain subdivided Nova Scotia in 1784 with the creation of the colonies of New Brunswick and Cape Breton Island; this had the effect of considerably diluting Halifax's presence over the region.

During the American Revolution, Halifax became the staging point of many attacks on rebel-controlled areas in the Thirteen Colonies, and was the city to which British forces from Boston and New York were sent after the over-running of those cities. After the War, tens of thousands of United Empire Loyalists from the American Colonies flooded Halifax, and many of their descendants still reside in the city today.

Napoleonic Wars

Halifax was now the bastion of British strength on the East Coast of North America. Local merchants also took advantage of the exclusion of American trade to the British colonies in the Caribbean, beginning a long trade relationship with the West Indies. However, the most significant growth began with the beginning of what would become known as the Napoleonic Wars. Military spending and the opportunities of wartime shipping and trading stimulated growth led by local merchants such as Charles Ramage Prescott and Enos Collins. By 1796, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, was sent to take command of Nova Scotia. Many of the city's forts were designed by him, and he left an indelible mark on the city in the form of many public buildings of Georgian architecture, and a dignified British feel to the city itself. It was during this time that Halifax truly became a city. Many landmarks and institutions were built during his tenure, from the Town Clock on Citadel Hill to St. George's Round Church, fortifications in the Halifax Defence Complex were built up, businesses established, and the population boomed.

War of 1812

.jpg)

Though the Duke left in 1800, the city's prosperity continued to grow throughout the Napoleonic Wars and War of 1812. While the Royal Navy squadron based in Halifax was small at the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars, it grew to a large size by the War of 1812 and ensured that Halifax was never attacked. The Naval Yard in Halifax expanded to become a major base for the Royal Navy and while its main task was supply and refit, it also built several smaller warships including the namesake HMS Halifax in 1806.[21] Several notable naval engagements occurred off the Halifax station. Most dramatic was the victory of the Halifax-based British frigate HMS Shannon which captured the American frigate USS Chesapeake and brought her to Halifax as prize. As well, an invasion force which attacked Washington in 1813, and burned the Capitol and White House was sent from Halifax. Early in the War, an expedition under Lord Dalhousie left Halifax to capture the Area of Castine, Maine, which they held for the entirety of the war. The revenues which were taken from this invasion were used after the war to found Dalhousie University which is today Halifax's largest university. The city also thrived in the War of 1812 on the large numbers of captured American ships and cargoes captured by the British navy and provincial privateers.

The wartime boom peaked in 1814. Present day government landmarks such as Government House, built to house the governor, and Province House, built to house the House of Assembly, were both built during the city's peak of prosperity at the end of the War of 1812.

Saint Mary's University was founded in 1802, originally as an elementary school. Saint Mary's was upgraded to a college following the establishment of Dalhousie University in 1819; both were initially located in the downtown central business district before relocating to the then-outskirts of the city in the south end near the Northwest Arm. Separated by only few minutes walking distance, the two schools now enjoy a friendly rivalry.

City of Halifax

The City of Halifax was established in 1842.

Crimean War

Nova Scotians fought in the Crimean War. The Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada (1860) and the only Crimean War monument in North America.[22] It commemorates the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855).

19th-century prosperity

In the peace after 1815, the city at first suffered an economic malaise for a few years, aggravated by the move of the Royal Naval yard to Bermuda in 1818. However the economy recovered in the next decade led by a very successful local merchant class. Powerful local entrepreneurs included steamship pioneer Samuel Cunard and the banker Enos Collins. During the 19th century Halifax became the birthplace of two of Canada's largest banks; local financial institutions included the Halifax Banking Company, Union Bank of Halifax, People's Bank of Halifax, Bank of Nova Scotia, and the Merchants' Bank of Halifax, making the city one of the most important financial centres in colonial British North America and later Canada until the beginning of the 20th century. This position was somewhat rivalled by neighbouring Saint John, New Brunswick during the city's economic hey-day in the mid-19th century.

Having played a key role to maintain and expand British power in North America and elsewhere during the 18th century, Halifax played less dramatic roles in the many decades of peace during the 19th Century. However as one of the most important British overseas bases, the harbour's defences were successively refortified with the latest artillery defences throughout the century to provide a secure base for British Empire forces. Nova Scotians and Maritimers were recruited through Halifax for the Crimean War. The city boomed during the American Civil War, mostly by supplying the wartime economy of the North but also by offering refuge and supplies to Confederate blockade runners. The port also saw Canada's first overseas military deployment as a nation to aid the British Empire during the Second Boer War.

Responsible government

The cause of self-government for the city of Halifax began the political career of Joseph Howe and would subsequently lead to this form of accountability being brought to colonial affairs for the colony of Nova Scotia. Howe was later considered a great Nova Scotian leader, and the father of responsible government in British North America. After election to the House of Assembly as leader of the Liberal party, one of his first acts was the incorporation of the City of Halifax in 1842, followed by the direct election of civic politicians by Haligonians.

Halifax became a hotbed of political activism as the winds of responsible government swept British North America during the 1840s, following the rebellions against oligarchies in the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada. The first instance of responsible government in the British Empire was achieved by the colony of Nova Scotia in January–February 1848 through the efforts of Howe. The leaders of the fight for responsible or self-government later took up the Anti-Confederation fight, the movement that from 1868 to 1875 tried to take Nova Scotia out of Confederation.

During the 1850s, Howe was a heavy promoter of railway technology, having been a key instigator in the founding of the Nova Scotia Railway, which ran from Richmond in the city's north end to the Minas Basin at Windsor and to Truro and on to Pictou on the Northumberland Strait. In the 1870s Halifax became linked by rail to Moncton and Saint John through the Intercolonial Railway and on into Quebec and New England, not to mention numerous rural areas in Nova Scotia.

American Civil War

The American Civil War again saw much activity and prosperity in Halifax. Due to longstanding economic and social connections to New England as well as the Abolition movement, a majority of the population supported the North and many volunteered to fight in the Union army. However, parts of the city's merchant class, especially those trading in the West Indies, supported the South. A few merchants in the city made huge profits selling supplies and sometimes arms to both sides of the conflict (see for example Alexander Keith, Jr.). Confederate ships often called on the port to take on supplies, and make repairs. One such ship, the CSS Tallahassee, became a legend in Halifax when she made a daring midnight escape through from northern warships believed waiting at the harbour entrance. Halifax was also played a significant role in the Chesapeake Affair.

Confederation

After the American Civil War, the five colonies which made up British North America, Ontario, Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, held meetings to consider uniting into a single country. This was due to a threat of annexation and invasion from the United States. Canadian Confederation became a reality in 1867, but received much resistance from the merchant classes of Halifax, and from many prominent Halifax politicians due to the fact that both Halifax and Nova Scotia were at the time very wealthy, held trading ties with Boston and New York which would be damaged, and did not see the need for the Colony to give up its comparative independence. After confederation Halifax retained its British military garrison until British troops were replaced by the Canadian army in 1906. The British Royal Navy remained until 1910 when the newly created Royal Canadian Navy took over the Naval Dockyard.

The city's cultural roots deepened as its economy matured. The Victorian College of Art was founded in 1887 (later to become the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.) Local artist John O'Brien excelled at portraits of the city's ships, yacht races and seascapes. The province's Public Archives and the provincial museum were founded in this period (first called the Mechanic's Institute, later the Nova Scotia Museum.)

After Confederation, boosters of Halifax expected federal help to make the city's natural harbor Canada's official winter port and a gateway for trade with Europe. Halifax's advantages included its location just off the Great Circle route made it the closest to Europe of any mainland North American port. But the new Intercolonial Railway (ICR) took an indirect, southerly route for military and political reasons, and the national government made little effort to promote Halifax as Canada's winter port. Ignoring appeals to nationalism and the ICR's own attempts to promote traffic to Halifax, most Canadian exporters sent their wares by train though Boston or Portland. No one was interested in financing the large-scale port facilities Halifax lacked. It took the First World War to at last boost Halifax's harbor into prominence on the North Atlantic.[23] Halifax business leaders attempted to diversity with manufacturing under Canada's National Policy creating factories such as the Acadia Sugar Refinery, the Nova Scotia Cotton Manufacturing Company, the Halifax Graving Dock and the Silliker Car Works. However this embrace with industrialization produced only modest results as most Halifax manufacturers found it hard to compete with larger firms in Ontario and Quebec.

World War I

It was in World War I that Halifax would truly come into its own as a world-class port and naval facility in the steamship era. The strategic location of the port with its protective waters of Bedford Basin sheltered convoys from German U-boat attack prior to heading into the open Atlantic Ocean. Halifax's railway connections with the Intercolonial Railway of Canada and its port facilities became vital to the British war effort during the First World War as Canada's industrial centres churned out material for the Western Front. In 1914, Halifax began playing a major role in the First World War, both as the departure point for Canadian soldiers heading overseas, and as an assembly point for all convoys (a responsibility which would be placed on the city again during WW2). Most Canadian troops left overseas from Halifax aboard enormous peacetime ocean liners converted to troopships such as RMS Olympic and RMS Mauretania as well as hundreds of other smaller liners. The city also served as the return point for a steady stream of wounded soldiers returning on hospital ships. A new generation of gun batteries, searchlights and an anti-submarine net defended the harbour, manned by a large garrison of soldiers. Halifax's limited 19th-century housing and transit facilities were heavily burdened. In November 1917, a subway system plan was presented to City Hall, but the city did not pursue the scheme.

Halifax Explosion

The war was seen as a blessing for the city's economy, but in 1917 a French munitions ship, the Mont Blanc, collided with a Norwegian ship, the Imo. The collision sparked a fire on the munitions ship which was filled with 2,300 tons of wet and dry picric acid (used for making lyddite for artillery shells), 200 tons of trinitrotoluene (TNT), 10 tons of gun cotton, with drums of benzole (high octane fuel) stacked on her deck. On December 6, 1917, at 9:04:35 AM[24] the munitions ship exploded in what was the largest man-made explosion before the first testing of an atomic bomb, and is still one of the largest non-nuclear man-made explosions. Items from the exploding ship landed five kilometres away. The Halifax Explosion decimated the city's north end, killing roughly 2,000 inhabitants, injuring 9,000, and leaving tens of thousands homeless and without shelter.

The following day a blizzard hit the city, hindering recovery efforts. Immediate help rushed in from the rest of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. In the following week more relief from other parts of North America arrived and donations were sent from around the world. The most celebrated effort came from the Boston Red Cross and the Massachusetts Public Safety Committee; as an enduring thank-you, since 1971 the province of Nova Scotia has donated the annual Christmas tree lit at the Boston Common in Boston.[25][26]

The explosion and the rebuilding which followed had important impacts on the city: reshaping the layout of North End neighbourhoods; creating a progressive housing development known as the Hydrostone; and hastening the move of railways to the South End of the City.

Between the wars

The city's economy slumped after the war, although reconstruction from the Halifax Explosion brought new housing and infrastructure as well as the establishment of the Halifax Shipyard. However, a tremendous drop in worldwide shipping following the war as well as the failure of regional industries in the 1920s brought hard-times to the city, further aggravated by the Great Depression in 1929. One bright spot was the completion of Ocean Terminals in the city's south end, a large modern complex to trans-ship freight and passengers from steamships to railways. The harbour's strategic location made the city the base for the famous and successful salvage tug Foundation Franklin which brought lucrative salvage jobs to the city in the 1930s. While a military airport had been in operation at Dartmouth's Shearwater base since WW I, the city opened its first civilian airport in the city's West End at Chebucto Field in 1931. Pan-Am began international flights from Boston in 1932.[27]

War Plan Red, a military strategy developed by the United States Army during the mid-1920s and officially withdrawn in 1939, involved an occupation of Halifax by US forces following a poison gas first strike, to deny the British a major naval base and cut links between Britain and Canada.

World War II

Halifax played an even bigger role in the Allied naval war effort of World War II. The only theatre of War to be commanded by a Canadian was the North Western Atlantic, commanded from Halifax by Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray. Halifax became a lifeline for preserving Britain during the Nazi onslaught of the Battle of Britain and the Battle of the Atlantic, the supplies helping to offset a threatened amphibious invasion by Germany. Many convoys assembled in Bedford Basin to deliver supplies to troops in Europe. The city's railway links fed large numbers of troopships building up Allied armies in Europe. The harbour became an essential base for Canadian, British and other Allied warships. Very much a front-line city, civilians lived with the fears of possible German raids or another accidental ammunition explosion. Well-defended, the city was never attacked although some merchant ships and two small naval vessels were sunk at the outer approaches to the harbour. However, the sounds and sometimes the flames of these distant attacks fed wartime rumours, some of which linger to the present day of imaginary tales of German U-Boats entering Halifax Harbour. The city's housing, retail and public transit infrastructure, small and neglected after 20 years of prewar economic stagnation was severely stressed. Severe housing and recreational problems simmered all through the war and culminated in the Halifax Riot on VE Day in May 1945. The war was also marked by a massive explosion of the Navy's Bedford ammunition magazine which accidentally blew up on July 18, 1945 causing the evacuation of the north end of Halifax and Dartmouth and fears of another Halifax Explosion

Bedford Magazine Explosion

During World War II Dartmouth as with Halifax was busy supporting Canada's war effort in Europe. On July 18, 1945, at the end of the Second World War, a fire broke out at the magazine jetty on the Bedford Basin, north of Dartmouth. The fire began on a sunken barge and quickly spread to the dock. A violent series of large explosions ensued as stored ammunition exploded. The barge responsible for starting the explosion presently lies on the seabed near the eastern shoreline adjacent to the Magazine Dock.

Post-war

After World War Two, Halifax did not experience the postwar economic malaise it had so often experienced after previous wars. This was partially due to the Cold War which required continued spending on a modern Canadian Navy. However, the city also benefited from a more diverse economy and postwar growth in government services and education. The 1960s–1990s saw less suburban sprawl than in many comparable Canadian cities in the areas surrounding Halifax. This was partly as a result of local geographies and topography (Halifax is extremely hilly with exposed granite not conducive to construction), a weaker regional and local economy, and a smaller population base than, for example, central Canada or New England. There were also deliberate local government policies to limit not only suburban growth but also put some controls on growth in the central business district to address concerns from heritage advocates.

The late 1960s was a period of significant change and expansion of the city when surrounding areas of Halifax County were amalgamated into Halifax: Rockingham, Clayton Park, Fairview, Armdale, and Spryfield were all added in 1969.

Urban renewal plans in the 1960s and 70s resulted in the loss of much of its heritage architecture and community fabric in large downtown developments such as the Scotia Square mall and office towers. However, a citizens protest movement limited further destructive plans such as a waterfront freeway which opened the way for a popular and successful revitalized waterfront. Selective height limits were also achieved to protect the views from Citadel Hill. However, municipal heritage protection remained weak with only pockets of heritage buildings surviving in the downtown and constant pressure from developers for further demolition. Selective height restrictions were adopted to protect views from Citadel Hill which triggered battles over proposed developments that would fill vacant lots or add height to existing historical structures.

Another casualty during the 1960s and 1970s period of expansion and urban renewal was the Black community of Africville which was declared a slum, demolished and its residents displaced to clear land for industrial use as well as for the A. Murray MacKay Bridge. The repercussions continue to this day and a 2001 United Nations report has called for reparations be paid to the community's former residents.

Restrictions on development were relaxed somewhat during the 1990s, resulting in some suburban sprawl off the peninsula. Today the community of Halifax is more compact than most Canadian urban areas although expanses of suburban growth have occurred in neighbouring Dartmouth, Bedford and Sackville. One development in the late 1990s was the Bayers Lake Business Park, where warehouse style retailers were permitted to build in a suburban industrial park west of Rockingham. This has become an important yet controversial centre of commerce for the city and the province as it used public infrastructure to subsidise multi-national retail chains and draw business from local downtown business. Much of this subsidy was due to competition between Halifax, Bedford and Dartmouth to host these giant retail chains and this controversy helped lead the province to force amalgamation as a way to end wasteful municipal rivalries. In the past few years, urban housing sprawl has even reached these industrial/retail parks as new blasting techniques permitted construction on the granite wilderness around the city. What was once a business park surrounded by forest and a highway on one side has become a large suburb with numerous new apartment buildings and condominiums. Some of this growth has been spurred by offshore oil and natural gas economic activity but much has been due to a population shift from rural Nova Scotian communities to the Halifax urban area. The new amalgamated city has attempted to manage this growth with a new master development plan.

Amalgamation

During the 1990s, Halifax amalgamated with its suburbs under a single municipal government. The provincial government had sought to reduce the number of municipal governments in the province as a cost-saving measure.[citation needed] A task force was created in 1992 to pursue this cutback.

In 1995, an Act to Incorporate the Halifax Regional Municipality received Royal Assent in the provincial legislature and the Halifax Regional Municipality (or HRM) was created on April 1, 1996. The HRM is an amalgamation of the municipal governments within Halifax County: the cities of Halifax and Dartmouth, the town of Bedford, and the Municipality of the County of Halifax. Sable Island, being part of Halifax County, is also jurisdictionally part of the HRM, despite being located 180 km offshore.

Although amalgamated cities in other provinces retained their original names, the HRM is officially referred to by its full name or its initials. The full name or initials are often used by media and by residents outside of the former City of Halifax instead of the unofficial "Halifax".[citation needed] However, the communities outside of the former City of Halifax have retained their names so as to avoid confusion.

Geography

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1749 | 2,576 | — |

| 1755 | 1,747 | −32.2% |

| 1762 | 2,500 | +43.1% |

| 1767 | 3,695 | +47.8% |

| 1790 | 4,000 | +8.3% |

| 1817 | 5,341 | +33.5% |

| 1828 | 14,439 | +170.3% |

| 1841 | 14,422 | −0.1% |

| 1851 | 20,749 | +43.9% |

| 1861 | 25,026 | +20.6% |

| 1871 | 29,582 | +18.2% |

| 1881 | 36,100 | +22.0% |

| 1891 | 38,437 | +6.5% |

| 1901 | 40,832 | +6.2% |

| 1911 | 46,619 | +14.2% |

| 1921 | 58,372 | +25.2% |

| 1931 | 59,275 | +1.5% |

| 1941 | 70,488 | +18.9% |

| 1951 | 85,589 | +21.4% |

| 1961 | 92,511 | +8.1% |

| 1971 | 122,035 | +31.9% |

| 1981 | 114,594 | −6.1% |

| 1986 | 113,577 | −0.9% |

| 1991 | 114,455 | +0.8% |

| 1996 | 113,910 | −0.5% |

| 2001 | 119,292 | +4.7% |

| 2006 | 130,130 | +9.1% |

| [28][29][30][31][32][33] The population change between 1961 and 1971 reflects Halifax's amalgamation in 1969. | ||

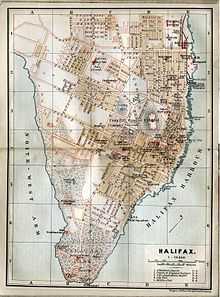

The original settlements of Halifax occupied a small stretch of land inside a palisade at the foot of Citadel Hill on the Halifax Peninsula, a sub-peninsula of the much larger Chebucto Peninsula that extends into Halifax Harbour. Halifax subsequently grew to incorporate all of the north, south, and west ends of the peninsula with a central business district concentrated in the southeastern end along "The Narrows".

In 1969, the City of Halifax grew westward of the peninsula by amalgamating several communities from the surrounding Halifax County; namely Fairview, Rockingham, Spryfield, Purcell's Cove, and Armdale. These communities saw a number of modern subdivision developments during the late 1960s through to the 1990s, one of the earliest being the Clayton Park development at the southwestern edge of Rockingham.

Since amalgamation into HRM, "Halifax" has been used variously to describe all HRM, all of urban HRM, and the area of the Halifax Peninsula and Mainland Halifax (which together form the provincially recognized Halifax Metropolitan Area) that had been covered by the dissolved city government.[34][35][36][37]

The communities of mainland Halifax that were amalgamated into the City of Halifax in 1969 are reasserting their identities[38][39] principally through the creation of the Mainland Halifax planning area, which is governed by the Chebucto Community Council.

Halifax is also located on the Appalachian land form region Halifax is in the Atlantic Maritime ecozone, wet climate soil region, mixwood forest vegetation region, Atlantic Canada Climate region.

The streets on the Halifax peninsula are a grid and numbered sequentially making it easy to get around. Numbered from south-to-north House Numbers start at 1 and reach 1000 block at Inglis Street, 2000 block at Quinpool Road, 3000 block at Almon Street and 4000 block at Duffus Street. Moving from east-to-west 5000 block is at Lower Water Street, 6000 block at Robie Street. One of the longest streets on the peninsula is Robie Street. When looking for 2010 Robie Street look one block north of Quinpool Road across fron the Halifax Commons, move a block to the west and you will find 2010 Windsor Street; walk a few more blocks west and Quinpool will take you to 2010 Oxford Street. If you are moving west on Almon Street you will find 5200 Almon at the Gottingen Street intersection, 6000 Almon at Robie, 7000 Almon at Connaught Ave., Chebucto Road numbers to 8000 at Joseph Howe Drive. The numbering system is consistent to the grid even when the streets are not perfectly parallel or perpendicular to one another on the map.

Neighbourhoods

- Colloquial neighbourhood names

- North End Halifax, north of North Street to Seaview Park

- West End, Halifax, West of Windsor Street, between North and South Streets to Joseph Howe Drive

- Quinpool district, Shopping and Dining area

- South End Halifax, South of South Street to Point Pleasant Park

- Spring Garden, shopping and dining area

- Central Halifax, the original city, between North Street and South Street, from Lower-Water Street to Windsor Street

- Official neighbourhood names

(including former villages, residential neighbourhoods; and modern names of housing developments and industrial parks)

- Armdale, village neighbourhood

- Bayer's Lake

- Beechwood Park

- Boulderwood

- Bridgeview

- Clayton Park

- Convoy Place

- Cowie Hill

- Fairmount

- Fairview,village neighbourhood

- Fernleigh

- Green Acres

- Hydrostone post Halifax Explosion re-development neighbourhood

- Jollimore, village neighbourhood

- Kent Park

- Leiblin Park

- Melville Cove

- Mulgrave Park, housing development in Mulgrave district

- Rockingham, village neighbourhood

- Sherwood Heights

- Spryfield, village neighbourhood

- Thornhill

- Wedgewood

- Westmount Subdivision

- Historic neighbourhood names

- Africville, now Seaview Park

- Richmond, now The North End east of Novalea Drive facing the harbour.

- Mulgrave (Halifax), north of Duffus Street, east of Gottingen Street in the North End.

- Needham (Halifax), now The Hydrostone and much of the North End west of Novalea Drive.

- Dutch Village, The West End west of Windsor Street

- Fort Massey, East of Robie Street from Duke Street to South Street

Richmond, Needham and Mulgrave were voting district names. Historically, these working-class Catholic neighbourhoods used their parish names: Saint Stephen's, Saint Joeseph's, Saint Patrick's. Today they are the integrated and prosperous North End; the neighbourhood names are no longer in common use and the parish boundaries no longer exist.

References

- ↑ McCann, L.D. "Halifax", The Canadian Encyclopedia (2000) p.1034

- ↑ ""Edward Cornwallis" ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography''". Biographi.ca. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ Nova Scotia Place Names

- ↑ "Mi'kmaq Online.org – Words, Pronunciation – Jipugtug (with audio clips)". MikmaqOnline.org. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "MapleSquare.com – Halifax's History – Jipugtug (or Chebucto)". MapleSquare.com. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ Paskal, Cleo (June 10, 2006). "The Toronto Star – Harbouring a host of delights". TheStar.com. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Halifax Nova Scotia Canada Information – proudly presented by Kanada News". Nova-Scotia-Kanada.de. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "DineAid.Com – Nova Scotia – Dartmouth – Chebucto, (the biggest harbour)". DineAid.com. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Halifax history". Macalester.edu. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ "Treaty of Aix la Chapelle". Canadahistory.com. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008; Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7

- ↑ Wicken, p. 181; Griffith, p. 390; Also see http://www.northeastarch.com/vieux_logis.html

- ↑ Thomas Atkins. History of Halifax City. Brook House Press. 2002 (reprinted 1895 edition). p 334

- ↑ Piers, Harry. The Evolution of the Halifax Fortress (Halifax, PANS, Pub. #7, 1947), p. 6 As cited in Peter Landry's. The Lion and the Lily. Vol. 1. Trafford Press. 2007. p. 370

- ↑ Thomas Atkins. History of Halifax City. Brook House Press. 2002 (reprinted 1895 edition). p 209

- ↑ "L.R. Fisher, ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''". Biographi.ca. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ Earle Lockerby. Pre-Deportation Letters from Ile Saint Jean. Les Cahiers. La Société historique acadienne. Vol. 42, No2. June 2011. pp. 99–100

- ↑ Raddall, Thomas Halifax: Warden of the North, (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart) p. 64

- ↑ Trevor Kenchington, "The Navy's First Halifax", Argonauta, Canadian Nautical Research Society, Vol. X, No. 2 (April 1993), p. 9

- ↑ Akins, Dr. Thomas B. History of Halifax City, p. 85.

- ↑ Julian Gwyn, Ashore and Afloat: The British Navy and the Halifax Naval Yard Before 1820, University of Ottawa Press (2004) ISBN 9780776605739

- ↑ James Cornall (November 10, 1998). Halifax:: South End. Arcadia Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7385-7272-7.

- ↑ James D. Frost, "Halifax: the Wharf of the Dominion, 1867–1914." Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 2005 8: 35–48.

- ↑ "CBC – Halifax Explosion – Disputes over Time". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ "Boston Common Holiday Tree Lighting Coming December 3", Press Release, Parks Department, City of Boston, November 13, 2009

- ↑ "Holiday Tree Lightings Begin November 23", Press Release, Parks Department, City of Boston, November 09, 2009

- ↑ ""History of the Halifax International Airport", ''Halifax International Airport Authority" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- ↑ , population by district 2006

- ↑ , Canada Year Book 1932

- ↑ [http://www66.statcan.gc.ca/eng/acyb_c1955-eng.aspx?opt=/eng/1955/195501660140_p. 140.pdf], Canada Year Book 1955

- ↑ , Canada Year Book 1967

- ↑ , 1996 Census of Canada: Electronic Area Profiles

- ↑ , 2001 Community Profiles

- ↑

- ↑ "Halifax events & festivals". Destination Halifax. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑

- ↑ "Nova Scotia Geographical Names". Nsplacenames.ca. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ "Spryfield and District Business Commission – Home". Spryfield.ca. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ "Chebucto Community Council Halifax Regional Municipality". Halifax.ca. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

Bibliography

- McCann, L.D. (1999). "Halifax". The Canadian Encyclopedia (year 2000 edition). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. pp. 1034–1036.

- Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008.

- Griffiths, Naomi Elizabeth Saundaus. From Migrant to Acadian: A North American border people, 1604–1755. Montreal, Kingston: McGill-Queen's UP, 2005.

- Murdoch, Beamish. A History of Nova Scotia, Or Acadia. Vol 2. LaVergne: BiblioBazaar, 2009. pp. 166–167

- Wicken, William. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press. 2002.

- Laffoley, Steven. Hunting Halifax: in search of history, mystery and murder. Pottersfield Press. 2007.

External links

- Akins, Thomas B., History of Halifax, 1895.

- HRM History

- Government House – Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Halifax Port Authority > Media Fact Sheet

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||