Circular shift

In combinatorial mathematics, a circular shift is the operation of rearranging the entries in a tuple, either by moving the final entry to the first position, while shifting all other entries to the next position, or by performing the inverse operation. A circular shift is a special kind of cycle, which in turn is a special kind of permutation. Formally, a circular shift is a permutation σ of the n entries in the tuple such that either

modulo n, for all entries i = 1, ..., n,

modulo n, for all entries i = 1, ..., n,

or

modulo n, for all entries i = 1, ..., n.

modulo n, for all entries i = 1, ..., n.

The result of repeatedly applying circular shifts to a given tuple are also called the circular shifts of the tuple.

For example, repeatedly applying circular shifts to the four-tuple (a, b, c, d) successively gives

- (d, a, b, c),

- (c, d, a, b),

- (b, c, d, a),

- (a, b, c, d) (the original four-tuple),

and then the sequence repeats; this four-tuple therefore has four distinct circular shifts. However, not all n-tuples have n distinct circular shifts. For instance, the 4-tuple (a, b, a, b) only has 2 distinct circular shifts. In general the number of circular shifts of an n-tuple could be any divisor of n, depending on the entries of the tuple.

In computer programming, a circular shift (or bitwise rotation) is a shift operator that shifts all bits of its operand. Unlike an arithmetic shift, a circular shift does not preserve a number's sign bit or distinguish a number's exponent from its mantissa. Unlike a logical shift, the vacant bit positions are not filled in with zeros but are filled in with the bits that are shifted out of the sequence.

Implementing circular shifts

Circular shifts are used often in cryptography in order to permute bit sequences. Unfortunately, many programming languages, including C, do not have operators or standard functions for circular shifting, even though several processors have bitwise operation instructions for it (e.g. Intel x86 has ROL and ROR). However, some compilers may provide access to the processor instructions by means of intrinsic functions. In addition, it is possible to write standard ANSI C code that compiles down to the "rotate" assembly language instruction (on CPUs that have such an instruction). Most C compilers recognize this idiom:

unsigned int x; unsigned int y; /* ... */ y = (x << shift) | (x >> (sizeof(x)*CHAR_BIT - shift));

and compile it to a single 32-bit rotate instruction.[1][2]

On some systems, this may be "#define"ed as a macro or defined as an inline function called something like "rightrotate32", "rotr32" or "ror32" in a standard header file like "bitops.h".[3] Rotates in the other direction may be "#define"ed as a macro or defined as an inline function called something like "leftrotate32", "rotl32" or "rol32" in the same "bitops.h" header file.

If necessary, circular shift functions can be defined (here in C):

/* We don't need special handling for certain shift values: * Shift operations in C are only defined for shift values which are * not negative and smaller than sizeof(value), but the compiler * will generate correct code for the following code pattern. */ unsigned int rotl(unsigned int value, int shift) { return (value << shift) | (value >> (sizeof(value) * 8 - shift)); } unsigned int rotr(unsigned int value, int shift) { return (value >> shift) | (value << (sizeof(value) * 8 - shift)); }

Example

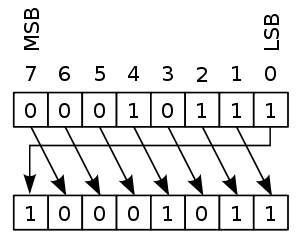

If the bit sequence 0001 0111 were subjected to a circular shift of one bit position... (see images below)

- to the left would yield: 0010 1110

- to the right would yield: 1000 1011.

If the bit sequence 0001 0111 were subjected to a circular shift of three bit positions...

- to the left would yield: 1011 1000

- to the right would yield: 1110 0010.

Applications

Cyclic codes are a kind of block code with the property that the circular shift of a codeword will always yield another codeword. This motivates the following general definition: For a string s over an alphabet Σ, let shift(s) denote the set of circular shifts of s, and for a set L of strings, let shift(L) denote the set of all circular shifts of strings in L. As already noted, if L is a cyclic code, we have L = shift(L). The operation shift(L) has been studied in formal language theory. For instance, if L is a context-free language, then shift(L) is again context-free.[4][5] Also, if L is described by a regular expression of length n, there is a regular expression of length O(n³) describing shift(L).[6]

See also

- Barrel shifter

- Bitwise operation

- Circulant

- Lyndon word

References

- ↑ GCC: "Optimize common rotate constructs"

- ↑ "Cleanups in ROTL/ROTR DAG combiner code" mentions that this code supports the "rotate" instruction in the CellSPU

- ↑ "replace private copy of bit rotation routines" -- recommends including "bitops.h" and using its rol32 and ror32 rather than copy-and-paste into a new program.

- ↑ T. Oshiba, "Closure property of the family of context-free languages under the cyclic shift operation", Transactions of IECE, 55D:119–122, 1972.

- ↑ A. N. Maslov, "Cyclic shift operation for languages", Problems of Information Transmission 9:333–338, 1973.

- ↑ Gruber, Hermann; Holzer, Markus (2009). "Language operations with regular expressions of polynomial size". Theoretical Computer Science 410 (35): 3281–3289. Zbl 1176.68105..