Chrysopogon zizanioides

| Chrysopogon zizanioides | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Monocots |

| (unranked): | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Chrysopogon |

| Species: | C. zizanioides |

| Binomial name | |

| Cymbopogon cintratus(citronella) (L.) Roberty | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Vetiveria zizanioides | |

Chrysopogon zizanioides, commonly known as vetiver (derived from Tamil word: வெட்டிவேர் vettiver) is a perennial grass of the Poaceae family, native to India. In western and northern India, it is popularly known as khus. Vetiver can grow up to 1.5 metres high and form clumps as wide. The stems are tall and the leaves are long, thin, and rather rigid; the flowers are brownish-purple. Unlike most grasses, which form horizontally spreading, mat-like root systems, vetiver's roots grow downward, 2–4 m in depth. Vetiver is most closely related to Sorghum but shares many morphological characteristics with other fragrant grasses, such as lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus), citronella (Cymbopogon nardus, C. winterianus), and palmarosa (Cymbopogon martinii). Though it originates in India, vetiver is widely cultivated in the tropical regions of the world. The world's major producers include Haiti, India, Java, and Réunion. The most commonly used commercial genotypes of vetiver are sterile (do not produce fertile seeds), and because vetiver propagates itself by small offsets instead of underground stolons, these genotypes are noninvasive and can easily be controlled by cultivation of the soil at the boundary of the hedge. However, care must be taken, because fertile genotypes of vetiver have become invasive.[1] Vegetatively propagated, almost all vetiver grown worldwide for perfumery, agriculture, and bioengineering has been shown by DNA fingerprinting to be essentially the same nonfertile cultigen (called 'Sunshine' in the United States, after the town of Sunshine, Louisiana).[2]

Morphology[3]

The vetiver grass has a gregarious habit and grows in bunches. Shoots growing from the underground crown make the plant frost- and fire-resistant, and allow it to survive heavy grazing pressure. The leaves can become up to 120–150 cm long and 0.8 cm wide.[4] The panicles are 15–30 centimeters long and have whorled, 2.5–5.0 centimeters long branches.[4] The spikelets are in pairs, and there are three stamens.

The plant stems are erect and stiff. They can persist deep water flow. Under clear water, the plant can survive up to two months.

The root system of vetiver is finely structured and very strong. It can grow 3–4 m deep within the first year. Vetiver has no stolons nor rhizomes. Because of all these characteristics, the vetiver plant is highly drought-tolerant and can help to protect soil against sheet erosion. In case of sediment deposition, new roots can grow out of buried nodes.

Uses

Vetiver grass is grown for many different purposes. The plant helps to stabilise soil and protects it against erosion, but it can also protect fields against pests and weeds. Vetiver has favourable qualities for animal feed. From the roots, oil is extracted and used for cosmetics and aromatherapy. Due to its fibrous properties, the plant can also be used for handicrafts, ropes and more.

Soil and water conservation

Erosion control

Several aspects of vetiver make it an excellent erosion control plant in warmer climates. Unlike most grasses, it does not form a horizontal mat of roots; rather, the roots grow almost exclusively downward, 2–4 m, which is deeper than some tree roots.[3] This makes vetiver an excellent stabilizing hedge for stream banks, terraces, and rice paddies, and protects soil from sheet erosion. The roots bind to the soil, therefore it can not dislodge. Vetiver has also been used to stabilize railway cuttings/embankments in geologically challenging situations in an attempt to prevent mudslides and rockfalls, the Konkan railway in Western India being an example. The plant also penetrates and loosens compacted soils.[3]

The Vetiver system, a technology of soil conservation and water quality management, is based on the use of the vetiver plant.

Runoff mitigation and water conservation

The close-growing culms also help to block the runoff of surface water. It slows water's flow velocity and thus increases the amount absorbed by the soil (infiltration). It can withstand a flow velocity up to 5 metres per second (16 ft/s).[3]

Vetiver mulch increases water infiltration and reduces evaporation, thus protects soil moisture under hot and dry conditions. The mulch also protects against splash erosion.[3]

Crop protection and pest repellent

Vetiver can be used for crop protection. It attracts the stem borer (Chilo partellus), which lay their eggs preferably on vetiver. Due to the hairy architecture of vetiver, the larvae can not move on the leaves, fall to the ground and die.

The essential oil of vetiver has anti-fungal properties against Rhizoctonia solani Kuhn[5]

As a mulch, vetiver is used for weed control in coffee, cocoa and tea plantations. It builds a barrier in the form of a thick mat. When the mulch breaks down, soil organic matter is built up and additional nutrients for crops become available.

Vetiver as a termite repellent

Studies by Prof. Gregg Henderson found that vetiver extracts could repel termites.[6][7] However, vetiver grass alone, unlike its extracts, cannot be used to repel termites. Henderson planted vetiver in trash cans and hammered wooden stakes into the soil filled cans. He offered large population of termites the ability to move into the trash cans via another trash can, but found that although the vetiver root completely filled the cans in 6 months, the stakes were still attacked. The termites had moved around the roots and got to the wood. Unless the roots are damaged, the anti-termite chemicals, such as nootkatone, are not released. Henderson reports that his research on the idea of protection of a home with vetiver planted as a barrier ended at that point. Another study found a similar result.[8]

Animal feed

The leaves of vetiver are a useful byproduct to feed cattle, goats, sheep and horses. The nutritional content depends on season, growth stage and soil fertility.[3] Under most climates, nutritional values and yields are best if vetiver is cut every 1–3 months.

| Young Vetiver | Mature Vetiver | Old Vetiver | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy [kcal/kg] | 522 | 706 | 969 |

| Digestibility [%] | 51 | 50 | - |

| Protein [%] | 13.1 | 7.93 | 6.66 |

| Fat [%] | 3.05 | 1.30 | 1.40 |

Food and Flavorings

Vetiver (Khus) is also used as a flavoring agent, usually through khus syrup. Khus syrup is made by adding khus essence to sugar, water and citric acid syrup. Khus Essence is a dark green thick syrup made from the roots of khus grass (vetiver grass). It has a woodsy taste and a scent prominent to khus.

The syrup is used to flavor milkshakes and yogurt drinks like lassi, but can also be used in ice creams, mixed beverages like Shirley Temples and as a dessert topping. Khus syrup does not need to be refrigerated, although khus flavored products may need to be.[9]

Perfumery and aromatherapy

Vetiver is mainly cultivated for the fragrant essential oil distilled from its roots. In perfumery, the older French spelling, vetyver, is often used. Worldwide production is estimated at about 250 tons per annum.[10] Due to its excellent fixative properties, vetiver is used widely in perfumes. It is contained in 90% of all western perfumes. Vetiver is a more common ingredient in fragrances for men; some notable examples include Dior's Eau Sauvage, Guerlain Vetiver, Zizan by Ormonde Jayne and Vetiver by L'Occitane.

Indonesia, China, Haiti are major producers.[10] Vetiver processing was introduced to Haiti in the 1940s by Frenchman Lucien Ganot.[11] In 1958, Franck Léger established a plant on the grounds of his father Demetrius Léger's alcohol distillery. The plant was taken over in 1984 by Franck's son, Pierre Léger, who expanded the size of the plant to 44 atmospheric stills, each built to handle one metric ton of vetiver roots. Total production increased in ten years from 20 to 60 tonnes annually, making it the largest producer in the world.[12] The plant extracts vetiver oil by steam distillation. Another major operation in the field is the one owned by the Boucard family. Réunion is considered to produce the highest quality vetiver oil called "bourbon vetiver" with the next favorable being Haiti and then Java.[citation needed]

The United States, Europe, India, and Japan are the main consumers.

Essential oil

Composition

Vetiver oil or khus oil is a complex oil, containing over 100 identified components, typically:[citation needed]

| benzoic acid | furfurol |

| vetivene | vetivenyl vetivenate |

| terpinen-4-ol | 5-epiprezizane |

| khusimene | α-muurolene |

| khusimone | Calacorene |

| β-humulene | α-longipinene |

| γ-selinene | δ-selinene |

| δ-cadinene | valencene |

| calarene,-gurjunene | α-amorphene |

| epizizanal | 3-epizizanol |

| khusimol | Iso-khusimol |

| valerenol | β-vetivone |

| α-vetivone | vetivazulene |

-

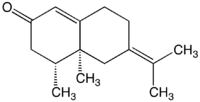

Structure of α-vetivone, the main fragrant component of the oil of vetiver

-

Structure of khusimol, another fragrant component of the oil of vetiver

-

Structure of β-vetivone, another fragrant component of the oil of vetiver

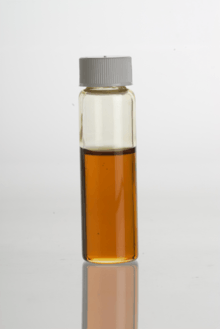

The oil is amber brown and rather thick. Its odor is described as deep, sweet, woody, smoky, earthy, amber, and balsam. The best quality oil is obtained from 18- to 24-month-old roots. The roots are dug up, cleaned, and then dried. Before the distillation, the roots are chopped and soaked in water. The distillation process can take up to 24 hours. After the distillate separates into the essential oil and hydrosol, the oil is skimmed off and allowed to age for a few months to allow some undesirable notes forming during the distillation to dissipate. Like patchouli and sandalwood essential oils, the odor of vetiver develops and improves with aging. The characteristics of the oil can vary significantly depending on where the grass is grown and the climate and soil conditions. The oil distilled in Haiti and Réunion has a more floral quality and is considered of higher quality than the oil from Java, which has a smokier scent. In the north of India, oil is distilled from wild-growing vetiver. This oil is known as khus or khas, and is considered superior to the oil obtained from the cultivated variety. It is rarely found outside of India, as most of it is consumed within the country.[citation needed]

Medicinal use

Vetiver has been used in traditional medicine in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and West Africa.[13]

Old Tamil literature mentions the use of vetiver for medical purposes.

In-house use

In the Indian Subcontinent, khus (vetiver roots) is often used to replace the straw or wood shaving pads in evaporative coolers.[4] When cool water runs for months over wood shavings in evaporative cooler padding, they tend to accumulate algae, bacteria and other microorganisms. This causes the cooler to emit a fishy or seaweed smell into the house. Vetiver root padding counteracts this smell. A cheaper alternative is to add vetiver cooler perfume or even pure khus attar to the tank. Another advantage is that they do not catch fire as easily as dry wood shavings.

Mats made by weaving vetiver roots and binding them with ropes or cords are used in India to cool rooms in a house during summer. The mats are typically hung in a doorway and kept moist by spraying with water periodically; they cool the passing air, as well as emitting a refreshing aroma.[citation needed]

In the hot summer months in India, sometimes a muslin sachet of vetiver roots is tossed into the earthen pot that keeps a household's drinking water cool. Like a bouquet garni, the bundle lends distinctive flavor and aroma to the water. Khus-scented syrups are also sold.[citation needed]

Fuel cleaning

A recent study found the plant is capable of growing in fuel-contaminated soil. In addition, the study discovered the plant is also able to clean the soil, so in the end, it is almost fuel-free.[14]

Other uses[3]

Vetiver grass is used as roof thatch (it lasts longer than other materials), mud brick-making for housing construction (such bricks have lower thermal conductivity), strings and ropes and ornamentals (for the light purple flowers).

Garlands made of vettiver grass is used to adorn The dancing god nataraja in the Hindu temples.

Agricultural aspects

Environmental requirements[3]

| Factor | Requirements |

|---|---|

| Soil type | Sandy loam soils are preferred. Clay loam is acceptable, but clay is not. |

| Topography | Slightly sloping land avoids waterlogging in case of overwatering. A flat site is acceptable, but watering must be monitored to avoid waterlogging, that will stunt the growth of young plantlets. Mature vetiver, however, thrives under waterlogged conditions. |

| Nutrition | It absorbs dissolved nutrients, such as N and P, and is tolerant to sodicity, magnesium, aluminium and manganese. |

| pH | Accepts soil pH from 3.3 to 12.5 (in another publication, 4.3–8.0)[4] |

| Soil conditions | Tolerant to salinity |

| Heavy metals | Absorbs dissolved heavy metals from polluted water, tolerates As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb, Hg, Se and Zn |

| Light | Shading affects vetiver growth (C4 plant), but partial shading is acceptable. |

| Temperature | It is tolerant to temperatures from −15°C to +55°C, depending on growing region. The optimal soil temperature for root growth is 25 °C. Root dormancy occurs under a temperature of 5 °C. Shoot growth is affected earlier; at 13 °C, shoot growth is minimal, but root growth is continued at a rate of 12.6 cm/day. Under frosty conditions, shoots become dormant and purple, or even die, but the underground growing points survive and can regrow quickly if the conditions improve. |

| Water | It is tolerant to drought (because of its deep roots), flood, and submergence; annual precipitation of 6.4–41.0 dm is tolerated, but it has to be at least 225 mm.[4] |

Crop management[3]

Vetiver is planted in long, neat rows across the slope for easy mechanical harvesting. The soil should be wet. Trenches are 15–20 cm deep.[15] A modified seedling planter or mechanical transplanter can plant large numbers of vetiver slips in the nursery. Flowering and nonflowering varieties are used for cultivation. Sandy loam nursery beds ensure easy harvest and minimal damage to plant crowns and roots. Open space is recommended, because shading affects vetiver growth.

Overhead irrigation is recommended for the first few months after planting. More mature plants prefer flood irrigation. Weed control may be needed during establishment phase, by using atrazine after planting.[4]

To control termites that attack dead material, hexachlorobenzene, also known as benzene hexachloride-BCH, can be applied to the vetiver hedge. Brown spot seems to have no effect on vetiver growth. Black rust in India is vetiver-specific and does not cross-infect other plants. In China, stemborers (Chilo spp.) have been recognised, but they seem to die once they get into the stems.[3] Further, vetiver is affected by Didymella andropogonis on leaves, Didymosphaeria andropogonis on dead culms, Lulworthia medusa on culms and Ophiosphaerella herpotricha. Only in Malaysia, whiteflies seem to be a problem. Pest management is done not only by using insecticides, but also by appropriate cultural management: hedges are cut to 3 cm above ground at the end of the growing season.[4] In general, vetiver is highly tolerant to herbicides and pesticides.

Note: Hexachlorobenzene is an animal carcinogen and is considered to be a probable human carcinogen. Its use is banned in the USA and in many other countries.

Harvest of mature plants is performed mechanically or manually. A machine uproots the mature stock 20–25 cm below ground. To avoid damaging the plant crown, a single-blade mouldboard plough or a disc plough with special adjustment should be used.

Notes

- ↑ http://www.vetiver.org/USA-USDA-NRCS_Sunshine.pdf

- ↑ Molecular Ecology 7:813–818

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 P. Truong, T. Tan Van, E. Pinners (2008). Vetiver Systems Application, Technical Reference Manual. The Vetiver Network International. p. 89.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 James A. Duke, Judith L duCellier. CRC Handbook of alternative cash crops.

- ↑ Nidhi Dubey, C.S. Raghav, R.L. Gupta and S.S. Chhonkar (2010) Pesticide Research Journal, 22(1):63-67.; Nidhi Dubey, R.L. Gupta & C.S. Raghav (2011) Ann. Pl. Protec. Sci., 19(1): 150-154.

- ↑ Zhu, BC.; Henderson, G.; Chen, F.; Fei, H.; Laine, RA. (Aug 2001). "Evaluation of vetiver oil and seven insect-active essential oils against the Formosan subterranean termite.". J Chem Ecol 27 (8): 1617–25. PMID 11521400.

- ↑ Maistrello, L.; Henderson, G.; Laine, RA. (Dec 2001). "Efficacy of vetiver oil and nootkatone as soil barriers against Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae).". J Econ Entomol 94 (6): 1532–7. PMID 11777060.

- ↑ Lee, Karmen C.; Mallette, Eldon J.; Arquette, Tim J (2012). "Field Evaluation of Vetiver Grass as a Barrier against Formosan Subterranean Termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae)". Journal of the Mississippi Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ↑ Tarla Dalal "Khus Syrup Glossary" in Tarladalal.com, India's #1 Food Site, 2012.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Karl-Georg Fahlbusch, Franz-Josef Hammerschmidt, Johannes Panten, Wilhelm Pickenhagen, Dietmar Schatkowski, Kurt Bauer, Dorothea Garbe, Horst Surburg "Flavors and Fragrances" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim: 2002. Published online: 15 January 2003; doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_141.

- ↑ The Fragrance Industry- Profiles c. 2007 by Glen O. Brechbill

- ↑ © International Trade Centre, International Trade Forum - Issue 3/2001

- ↑ Narong Chomchalow, "The Utilization of Vetiver as Medicinal and Aromatic Plants with Special Reference to Thailand", Office of the Royal Development Projects Board, Bangkok, Thailand September 2001, Pacific Rim Vetiver Network Technical Bulletin No. 2001/1.

- ↑ ynet.co.il The plant that cleans the ground (in Hebrew).

- ↑ Greenfield, John C. (2008). The Vetiver System for Soil and Water Conservation. ISBN 1-4382-0322-5.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chrysopogon zizanioides. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Chrysopogon zizanioides |

- Production of Vetiver Oil in Haiti

- Germplasm Resources Information Network: Chrysopogon zizanioides

- Veldkamp, J. F. (1999). A revision of Chrysopogon Trin., including Vetiveria Bory (Poaceae) in Thailand and Malesia with notes on some other species from Africa and Australia. Austrobaileya 5: 522–523.

- Other Uses and Utilization of Vetiver: Vetiver Oil - U.C. Lavania - Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Lucknow-336 015, India

- E. Guenther, The Essential Oils Vol. 4 (New York: Van Nostrand Company INC, 1990), 178–181, cited in Salvatore Battaglia, The Complete Guide to Aromatherapy (Australia: The Perfect Potion, 1997), 205.]

- Ruh Khus (Wild Vetiver Oil)/Oil of Tranquility - Christopher McMahon

External links

- The Vetiver Network International

- Frager Vetiver

- Caldecott, Todd (2006). Ayurveda: The Divine Science of Life. Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 0-7234-3410-7. Contains a detailed monograph on Chrysopogon zizanioides (Ushira), as well as a discussion of health benefits and usage in clinical practice. Available online at http://www.toddcaldecott.com/index.php/herbs/learning-herbs/338-ushira