Chronaxie

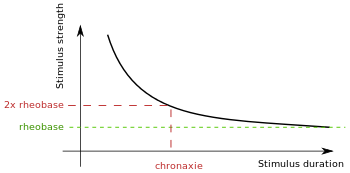

Chronaxie is the minimum time required for an electric current double the strength of the rheobase to stimulate a muscle or a neuron. Rheobase is the lowest intensity with indefinite pulse duration which just stimulated muscles or nerves.[1] Chronaxie is dependent on the density of voltage-gated sodium channels in the cell, which affect that cell’s excitability. Chronaxie varies across different types of tissue: fast-twitch muscles have a lower chronaxie, slow-twitch muscles have a higher one. Chronaxie is the tissue-excitability parameter that permits choice of the optimum stimulus pulse duration for stimulation of any excitable tissue. Chronaxie (c) is the Lapicque descriptor of the stimulus pulse duration for a current of twice rheobasic (b) strength, which is the threshold current for an infinitely long-duration stimulus pulse. Lapicque showed that these two quantities (c,b) define the strength-duration curve for current: I = b(1+c/d), where d is the pulse duration. However, there are two other electrical parameters used to describe a stimulus: energy and charge. The minimum energy occurs with a pulse duration equal to chronaxie. Minimum charge (bc) occurs with an infinitely short-duration pulse. Choice of a pulse duration equal to 10c requires a current of only 10% above rheobase (b). Choice of a pulse duration of 0.1c requires a charge of 10% above the minimum charge (bc).

History

The terms chronaxie and rheobase were first coined in Louis Lapicque’s famous paper on D´efinition exp´erimentale de l’excitabilit ´e that was published in 1909.[2]

The above I(d) curve is usually attributed to Weiss (1901) - see e.g. (Rattay 1990). It is the most simplistic of the 2 'simple' mathematical descriptors of the dependence of current strength on duration, and it leads to Weiss' linear charge progression with d:

\[ Q(d) = d.I = b.(d + c) \]

Both Lapicque's own writings and more recent work are at odds with the linear-charge approximation. Already in 1907 Lapicque was using a linear first-order approximation of the cell membrane, modeled using a single-RC equivalent circuit. Thus:

\[ I(d) = b / (1 - e^{-d/\tau}) \]

where $\tau=R C$ is the membrane time constant - in the 1st-order linear membrane model:

\[ C dv/dt + v/R = I, v == V-V_{rest} \]

Notice that the chronaxie (c) is not explicitly present here. Notice also that - with very short duration $d \ll \tau$, by the Taylor series decomposition of the exponent (around d=0):

\[ I(d) \approx b \tau / d \]

which leads to a constant-charge approximation. Interestingly, the latter may fit well also more complex models of the excitable membrane, which take into account ion-channel gating mechanisms, as well as intracellular current flow, which may be the main contributors for deviations from both simple formulas.

These 'subtleties' are clearly described by Lapicque (1907, 1926 and 1931), but not too well by Geddes (2004) who emphasized the Weiss level, attributing it to Lapicque.

Measurement

An electrode is inserted into the muscle of interest, which is then stimulated using surface current. Chronaxie values increase resulting from hyperventilation can be ascribed to a change in skin impedance, the physiological factors responsible for this change being under the influence of the autonomic nervous system. This example of the preponderating influence which the condition of the skin and the underlying tissues may exert compels caution in judging the results of chronaxie measurements by percutaneous stimulation.[3] A fresh and normal sartorius placed straight in a Ringer solution and stimulated through the solution without any direct contact with the electrodes is subject to give two very distinct strength-duration curves, one of them being spread over several hundredths of a second.[4]

Values

The chronaxie values for mammalian ventricles at body temperature range from 0.5 ms (human) to 2.0 to 4.1 ms (dog); this is a 8.2/1 ratio. It has been reported that large-diameter myelinated axons have chronaxie times ranging from 50 to 100 ms and 30 to 200 ms, and neuronal cell bodies and dendrites have chronaxie times ranging from 1 to 10 ms or even up to 30 ms. The chronaxie times of grey matter were reportedas being 380 +/- 191 ms and 200±700 ms. Interpretations of chronaxie times are further confounded by additional factors. The chronaxie times reported for soma and dendrites have been established using intracellular pulses that cannot be readily extrapolated to extra- cellular stimuli. Data reported in the literature use either motor response as the physiological threshold in humans or action potential generation in animals. These are largely based on stimulation through a macro-electrode, which in the case of humans is a 1.5 Â 1.2-mm DBS electrode. Data derived from micro-electrode stimulation and physiological mapping of sensory thalamus are scarce. The two stimulation methods may result in significantly different results. Few studies have attempted to correlate chronaxie times with sensory perception, although understanding the neural elements that are involved in a subjective percept, such as tingling, has important physiological implications.[5] The measurements were taken with different types of electrodes and with stimulators having unknown output impedances. The chronaxie values for human arm sensory nerves range from 0.35 to 1.17 ms, a ratio of 3.3. The values were obtained with insufficient information to establish the cause of variability. The chronaxie values for human denervated skeletal muscle ranges from 9.5 to 30 ms at body temperature, representing a ratio of 3.16. A reduction in chronaxie occurs during reinnervation. The published values for chronaxie have a wide range. If chronaxie is the best descriptor of tissue excitability in a homogeneous tissue specimen, at a known temperature, it should be determined with a constant-current stimulator providing a rectangular cathodal stimulus waveform. Chronaxie is derived from the strength-duration curve for current and it shows that if the stimulus duration is shorter than chronaxie, more current is required to stimulate, with any type or location of electrodes with a stimulator of any known or unknown output impedance. In addition, the chronaxie value, however determined, identifies the pulse duration for minimum energy. In addition, the charge delivered at chronaxie, however determined, is 2, twice the minimum charge. Therefore, if minimum charge delivery is sought to prolong the life of a battery in an implanted stimulator, a pulse duration of less than the measured chronaxie should be selected; a duration of one-tenth chronaxie provides a charge that is only 10% above the minimum charge.[6]

Stimulation

Electric and magnetic stimulation produced different sensations. For electric stimulation, sensation was typically described as localized directly below the electrodes on the surface of the skin. For magnetic stimulation, sensation was typically described as distributed throughout the palm and digits of the hand. In particular, most subjects reported sensations in either the medial or lateral digits. These observations suggest that electrical stimulation may preferentially activate cutaneous afferent nerve fibers whereas magnetic stimulation may preferentially activate deeper nerves, such as the ulnar or median nerve.

Motor vs Sensory

Other studies have compared the activation of sensory and motor fibers using electric and magnetic stimulation demonstrated through stimulation of nerve and muscle tissue that magnetic activation of intramuscular nerve fibers in the arm and leg occurs at a lower threshold than for electric stimulation. Also, sensory fibers were shown to have a lower threshold for electric stimulation. Electric stimulation of the wrist by determined that when short pulses are used (less than 200 μs), motor fibers are more readily excitable, whereas for long pulse durations (greater than 1000 μs), sensory fibers are more prone to depolarization. A related observation is that electric stimulation preferentially activates sensory fibers compared to motor fibers for long pulse durations, and the inverse for short pulse durations. For magnetic stimulation, the motor fiber threshold was lower than that for sensory fibers.[7]

Significance

The main value of chronaxie is comparing excitability across different experiments and measurements using the same standard, thus making data comparisons easier. Electrical stimulation based on chronaxie could regulate myoD gene expression in denervated muscle fibers. 20 muscle contractions, induced by electrical stimulation using surface electrodes and applied on alternate days based on muscle excitability, similar to protocols used in human clinical rehabilitation, were able to reduce the accumulation of mRNA in the myoD and atrogin-1 of denervated muscles, these expressions being related to muscle growth and atrophy, respectively. The increase in myoD levels after denervation is possibly related not only to activation and proliferation of the satellite cells but also to regulation of the cell cycle. Several studies have suggested that the function of denervation-induced myoD may be to prevent the muscle atrophy induced by denervation.[8] To assess contractility of denervated leg muscles, rheobase and chronaxie were determined in anaesthetized rat by surface electrical stimulation and palpation of the leg muscles. The values of chronaxie of TA muscle measured up to 9-month after sciatectomy. Muscle excitability decreased early after denervation. Chronaxie from 0.1-0.2 ms in innervated muscle changed to 0.5-1 ms within one to two days after denervation (i.e., after Wallerian degeneration of the nerve) and progressively increased to about 20 ms during the following month. Chronaxie remained at this level up to 6 months postsciatectomy (Mid-term denervation stage in the rat model: from 2 to 6 months sciatectomy). Afterwards, the twitch contraction became questionably palpable and thus chronaxie increased to much longer values (from 50 ms to infinitum, i.e., the muscle twitch was not palpable). This third stage is defined as the “long-term denervation stage” of the rat model, i.e., denervation time longer than six months). In 3 out of 36 leg muscles, reinnervation occurred spontaneously and chronaxie shortened to 0.1 ms, which is the value of normal innervated muscle.

Medical Use

Chronaxie and excitability values’ medical application is electromyography, a technique for evaluating and recording the electrical activity produced by skeletal muscle. Rheobase may not necessarily be the electrical current of choice. Electromyography is used to diagnose neuropathies, myopathies, and neuromuscular junction diseases.

Since persons affected by SCI may be treated with FES to maintain and/or improve muscle trophism/ function, the presence of excitable muscle fibers in long-term denervated muscle, could be extremely important for their treatment with FES. Of course, the pool of long term patients outnumbers new cases per year, the option to start even long term after spinal cord injury, i.e., at a time at which mechanical muscle twitches could not be detected by direct electrical stimulation, either by surface or intramuscular electrodes and could strongly support the choice to start and the motivation to lifelong perform FES exercise activity in these critical subjects.[9][10]

Diseases

Chronaxie is increased in the tetany of parathyreoidectomyis. It must be remembered, however, that it is the rheobase which corresponds to the x.c.c. of electrical reactions and that that does show a definite reduction. The rheobase depends for its value on the electrical resistance between the two electrodes as well as on the state of excitability of the stimulated motor point and therefore the decrease in the rheobase in tetany might imply no more than a decrease in the electrical resistance of the skin. It is difficult to see, however, how such an alteration of resistance could lead to the increased excitability to mechanical stimuli unless it is that these reactions are reflexes through the proprioceptive nerves. The chronaxie, on the other hand, does not depend on the interelectrode resistance but on the time relations of the excitation process, and when the chronaxie is increased, as in parathyroidectomy, it means that the intensity of twice the rheobase must act on the tissues for a longer period than is normal before the excitation process is set going.[11]

Drug interactions and Toxins

Acute intoxication of rats with aldrin decreases chronaxie, whereas chronic exposure to this chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticide has the reverse effect. Chronic exposure of rats to the closely related epoxide, dieldrin, has been suggested to reduce their muscular efficiency in performing a work exercise. Dieldrin is a chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticide widely used in crop protection and preservation. Among the diverse symptoms resulting from intoxication are muscular twitching increasing in severity to epileptiform convulsions with loss of consciousness. Strychnine, which has a spinal locus of activity, causes tonic hind limb extension in mice, which is thought to be due to a removal of the effect of inhibitory interneurons on the nervous pathway to extensor muscles. Leptazol, on the other hand, produces a similar tonic extension by an excitatory action predominantly on cerebral structures. Diphenylhydantoin selectively elevated the threshold convulsive dose of leptazol but not that of strychnine hydrochloride, indicating an anticonvulsant activity on the nervous pathway between the predominant locus of activity of leptazol and the hind limbs.[12]

See also

|

References

- ↑ IRNICH, W. (1980), The Chronaxie Time and Its Practical Importance. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 3: 292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1980.tb05236.x

- ↑ IRNICH, W. (2010), The Terms “Chronaxie” and “Rheobase” are 100 Years Old. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 33: 491–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02666.x

- ↑ Dijkstra, B., Dirken, M. N. J., (1939) The effect of forced breathing on the motor chronaxie. J Physiol. 96(2): 109–117. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1393855/

- ↑ Lapicque, L. (1931) Has the muscular substance a longer chronaxie than the nervous substance? The Journal of Physiology 73: 189-214. Retrieved from http://jp.physoc.org/content/73/2/189.full.pdf

- ↑ Anderson et al. (2003) Neural substrates of microstimulation-evoked tingling: a chronaxie study in human somatosensory thalamus. European Journal of Neuroscience 18: 728-732. Retrieved from http://people.ucalgary.ca/~zkiss/publications/2576chronaxie_paper.pdf

- ↑ Geddes, L. A. (2004) Accuracy Limitations of Chronaxie Values. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 51,1: 176-181. Retrieved from http://clarke.physics.uwo.ca/JournalClubPDF/Accuracy.pdf

- ↑ Chronik, B. A., Recoskie, B. J., Scholl, T. J. (2009) The discrepancy between human peripheral nerve chronaxie times as measured using magnetic and electric field stimuli: the relevance to MRI gradient coil safety. Phys. Med. Biol. 54: 5965–5979. Retrieved from http://www.imaging.robarts.ca/scholl/sites/imaging.robarts.ca.scholl/files/2.pdf

- ↑ Freria et al. (2007) Electrical stimulation based on chronaxie reduces atrogin-1 and myod gene expression in denervated rat muscle. Muscle Nerve 35: 87-97. Retrieved from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mus.20668/pdf

- ↑ Adami et al. (2007) Permanent denervation of rat Tibialis Anterior after bilateral sciatectomy: Determination of chronaxie by surface electrode stimulation during progression of atrophy up to one year. Basic Appl Myol 17 (6): 237-243. Retrieved from http://www.bio.unipd.it/bam/PDF/17-6/Adami.pdf

- ↑ Kern H, Carraro U, Adami N, Biral D, Hofer C, Forstner C, Mödlin M, Vogelauer M, Pond A, Boncompagni S, Paolini C, Mayr W, Protasi F, Zampieri S. (2010) Home-based functional electrical stimulation rescues permanently denervated muscles in paraplegic patients with complete lower motor neuron lesion. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010 Oct;24(8):709-21. doi: 10.1177/1545968310366129. Epub 2010 May 11. PMID:20460493

- ↑ Buchanan, D. N., Garven, H. S. D. (1926) Chronaxie in tetany. The effect on the chronaxie of thyreoparathyreoidectomy, the administration of guanidin and of di-methyl guanidin. J Physiol. 62(1): 115–128. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1514884/?page=1

- ↑ Natoff I. L., Reiff, B. (1967) The effect of diedrin (heod) on chronaxie and convulsion thresholds in rats and mice. Br. J. Pharmac. Chemother. 31: 197-204. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb01990.x/pdf