Christianity in Iran

| ||||||||||

Christianity by Country |

|---|

|

North America

South America

Oceania

|

Christianity in Iran has a long history, dating back to the early years of the faith. It is older than the State Religion, Islam itself. It has always been a minority religion, with the majority state religions — Zoroastrianism before the Islamic conquest, Sunni Islam in the Middle Ages and Shia Islam in modern times — though it had a much larger representation in the past than it does today. Christians of Iran have played a significant part in the history of Christian mission. Today, there are at least 600 churches for 250,000 Christians in Iran.[1]

Main denominations

The main Christian churches are:

- Armenian Apostolic Church of Iran (between 110,000[2] and 250,000 adherents[3])

- Assyrian Church of the East of Iran (about 11,000 adherents),[4]

- Chaldean Catholic Church of Iran (about 7,000 Assyrian adherents),[4]

- various other denominations, some examples are:

- Presbyterian, including the Assyrian Evangelical Church

- Pentecostal, including the Assyrian Pentecostal Church

- Jama'at-e Rabbani (the Iranian Assemblies of God churches)

- and the Anglican Diocese of Iran.

According to Operation World, there are between 7,000 and 15,000 members and adherents of the various Protestant, Evangelical and other minority churches in Iran,[4] though these numbers are particularly difficult to verify under the current political circumstances. [citation needed]

The International Religious Freedom Report 2004 by the U.S. State Department quotes a somewhat higher total number of 300,000 Christians in Iran, and states the majority of whom are ethnic Armenians followed by ethnic Assyrians.[5]

History

According to Acts 2:9 in the Acts of the Apostles there were Persians, Parthians and Medes among the very first new Christian converts at Pentecost. Since then there has been a continuous presence of Christians in Iran.

During the apostolic age, Christianity began to establish itself throughout the Mediterranean. However, a quite different Semitic Christian culture developed on the eastern borders of the Roman Empire and in Persia. Syriac Christianity owed much to preexistent Jewish communities and the Aramaic language. This language was spoken by Jesus, and, in various modern Eastern Aramaic forms is still spoken by the ethnic Assyrian Christians in Iran, northeast Syria, southeast Turkey and Iraq today (see Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic and Senaya language).

From Persian ruled Assyria (Assuristan), missionary activity spread Eastern Rite Syriac Christianity throughout Assyria and Mesopotamia, and from there into Persia, Asia Minor, Syria, the Caucasus and Central Asia, establishing the Saint Thomas Christians of India and the Nestorian Stele and Daqin Pagoda in China.

Early Christian communities straddling the Roman-Persian border were in the midst of civil strife. In 313, when Constantine I proclaimed Christianity to be a tolerated religion in the Roman Empire, the Sassanid rulers of Persia adopted a policy of persecution against Christians, including the double-tax of Shapur II in the 340s. Christians were feared as a subversive and possibly disloyal minority. In the early 5th century official persecution increased once more. However, from the reign of Hormizd III (457–459) serious persecutions grew less frequent and the church began to achieve recognised status. Political pressure within Persia and cultural differences with western Christianity were mostly to blame for the Nestorian schism, in which the Church of the East was labelled heretical. The bishop of the capital of the Sassanid Empire, Ctesiphon, acquired the title first of catholicos, and then patriarch completely independent of any Roman/Byzantine hierarchy.

Persia is considered by some to have been briefly officially Christian. Khosrau I married a Christian wife, and his son Nushizad was also a Christian. When the king was taken ill at Edessa a report reached Persia that he was dead, and at once Nushizad seized the crown and made the kingdom Christian. Very soon the rumour was prove false, but Nushizad was persuaded by persons who appear to have been in the pay of Justinian to endeavour to maintain his position. The action of his son was deeply distressing to Khosrau; it was necessary to take prompt measures, and the commander, Ram Berzin, was sent against the rebels. In the battle which followed Nushizad was mortally wounded and carried off the field. In his tent he was attended by a Christian bishop, probably Mar Aba I, and to this bishop he confessed his sincere repentance for having taken up arms against his father, an act which, he was convinced, could never win the approval of Heaven. Having professed himself a Christian he died, and the rebellion was quickly put down.

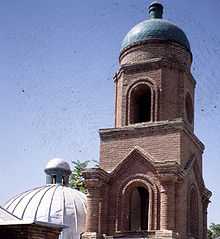

Many old churches remain in Iran from the early days of Christianity. The Church of St. Mary in northwestern Iran for example, is considered by some historians to be the second oldest church in Christendom after the Church of Bethlehem in the West Bank. A Chinese princess, who contributed to its reconstruction in 642 AD, has her name engraved on a stone on the church wall. The famous Italian traveller Marco Polo also described the church in his visit.

The Arab Islamic conquest of Persia, in the 7th century, was originally beneficial to Christians as they were a protected minority under Islam. However, from about the 10th century religious tension led to persecution once more. The influence of European Christians placed Near Eastern Christians in peril during the Crusades. From the mid-13th century, Mongol rule was a relief to Persian Christians until the Mongols adopted Islam. The Christian population gradually declined to a small minority. Christians disengaged from mainstream society and withdrew into ethnic ghettos (mostly Assyrian Aramaic and Armenian speaking). Persecution against Christians arose again in 14th century; when the Muslim warlord of Turco-Mongol descent Timur (Tamerlane) conquered Persia, Mesopotamia, Syria, and Asia Minor, he ordered large-scale massacres of Christians in Mesopotamia, Persia, Asia Minor and Syria. Most of the victims were indigenous Assyrians, Arameans and Armenians, members of the Assyrian Church of the East and Orthodox Churches.

In 1445, a part of the Assyrian Aramaic-speaking Church of the East entered into communion with the Catholic Church (mostly in the Ottoman Empire, but also in Persia). This group had a faltering start but has existed as a separate church since the consecration of Yohannan Sulaqa as Chaldean Patriarch of Babylon in 1553 by the pope. Most Assyrian Catholics in Iran today are members of the Chaldean Catholic Church. The Aramaic-speaking community that remains independent is the Assyrian Church of the East. Both churches now have much smaller memberships in Iran than the Armenian Apostolic Church.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Protestant missionaries began to evangelize Persia. Work was directed towards supporting the extant churches of the country while improving education and health care. Unlike the older, ethnic churches, these evangelical Protestants began to engage with the ethnic Persian Muslim community. Their printing presses produced much religious material in various languages. Some Persians subsequently converted[6] to Protestantism and their churches still exist within Iran (using the Persian language).

Current situation

In 1976, the Christian population numbered 168,593 people, mostly Armenians. Due to the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, almost half of the Armenians migrated to the newly independent Republic of Armenia. However, the opposite trend has occurred since 2000, and the number of Christians with Iranian citizenship increased to 109,415 in 2006. At the same time, significant immigration of Assyrians from Iraq has been recorded due to massacres and harassment in post-Saddam Iraq. However, most of those Assyrians in Iran don't have Iranian citizenship. In 2008, the central office of the International Union of Assyrians was officially transferred to Iran after being hosted in the United States for more than four decades.[7]

| Census | Christians | Total | Percentage | +/- |

| 1976[8] | 168,593 | 33,708,744 | 0.500% | ... |

| 1986[8] | 97,557 | 49,445,010 | 0.197% | -42% |

| 1996[9] | 78,745 | 60,055,488 | 0.131% | -19% |

| 2006[10] | 109,415 | 70,495,782 | 0.155% | +39% |

The government guarantees the recognized Christian minorities a number of rights (production and sale of non-halal foods), [citation needed] representation in parliament, special family law etc.[citation needed] According to US-based Barnabas Fund, government intrusion, expropriation of property, forced closure and persecution, particularly in the initial years after the Iranian Revolution, have all been documented.[citation needed] Youcef Nadarkhani is an Jammiat-e Rabbani pastor allegedly "sentenced to death for refusing to recant his faith".[11] However, Iranian official sources has described such claims as "propaganda".[12]

Iranian Christians tend to be urban, with 50% living in Tehran.[13] There are Satellite networks like Mohabbat TV and Sat7Pars that distribute educational and encouraging programs for Christians, especially targeting Persian speakers. Some Christian ex-Muslims emigrate from Iran for educational, political, security or economic reasons.[14][15][16][17]

The Bible in languages of Iran

Armenian and Assyrian Christians use Bibles in their own languages.

Multiple Persian translations and versions of the Bible have been translated in more recent times.

Portions of the Bible are translated into Azeri (New Testament, Jesus Film),[18] Mazanderani (portions), Gilaki (Gospel of John, Story of Joseph, Jesus Film),[19] Bakhtiari (portions, Jesus Film),[20] Luri (portions, Jesus Film)[21] and Kurdish (the Gospels).

See also

- Roman Catholicism in Iran

- Religious Minorities in Iran

- Christians in the Persian Gulf

- Armenian-Iranians

- Assyrians in Iran

Further Literature

- Gillman, Ian and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Christians in Asia before 1500, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Foltz, Richard (2004). Spirituality in the Land of the Noble: How Iran Shaped the World's Religions. Oxford: Oneworld publications. ISBN 1-85168-336-4.

- A Brief History of Christianity in Iran by Massoume Price

- Moffett, Samuel Hugh, A History of Christianity in Asia: Beginnings to 1500, San Francisco, Harper and Row, 1992.

- Statistical Information from: Operation World Website

- Christian architecture in Iran

- RFE/RL article on Christians in Iran

- Bradley, Mark, Iran and Christianity: Historical Identity and Present Relevance Continuum, London, 2008

- Jenkins, Philip, The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia and How it Died, HarperOne, New York, 2008

External links

- FarsiNet Large Iranian Christian internet portal (mostly evangelical)

- www. IranChurches.ir The Base of Iranian Historic Churches

- Online Kelisa Iranian Virtual Church

- www. christforiran.com Iranian Christian resources

- A Cry from Iran – an award winning documentary video (DVD) telling the story of some Iranian Christian martyrs

- www. Irankelisa.com Virtual Iranian seminary for Christians residing in Iran.

- www. gilakmedia.com Gilak Media – Digital Scripture in Video, Audio and Print form in the Gilaki language.

- Christchurch Teheran

References

- ↑ Ahmadinejad: Religious minorities live freely in Iran (PressTV, 24 Sep 2009)

- ↑ "In Iran, 'crackdown' on Christians worsens". Christian Examiner (Washington D.C.: Christian Examiner). April 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ↑ Price, Massoume (December 2002). "History of Christians and Christianity in Iran". Christianity in Iran. FarsiNet Inc. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 http://www.operationworld.org/country/iran/owtext.html

- ↑ U.S. State Department (26 October 2009). "Iran – International Religious Freedom Report 2009". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ↑ Cate, Patrick; Dwight Singer (1980). A Survey of Muslim Converts in Iran. pp. 1–16.

- ↑ Tehran Times: Assyrians’ central office officially transferred to Iran

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Statistical Centre of Iran: 6. Followers of selected religions in the 1976 & 1986 censuses

- ↑ Statistical Centre of Iran: 2. 17. Population by religion and ostan, 1375 census

- ↑ Statistical Centre of Iran: 2. 15. Population by religion and ostan, 1385 census

- ↑ Banks, Adelle M. (28 September 2011). [http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/on-faith/us-christians-rally-around-iranian-pastor/2011/09/28/gIQA11YJ5K_story. html&title=Iranian%20Pastor%20Youcef%20Nadarkhani's%20potential%20execution%20rallies%20U. S.%20Christians "Iranian Pastor Youcef Nadarkhani's potential execution rallies U.S. Christians"]. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2011. "Religious freedom advocates rallied Wednesday (Sept. 28) around an Iranian pastor who is facing execution because he has refused to recant his Christian faith in the overwhelmingly Muslim country."

- ↑ PressTV: Iran denies death penalty for convert

- ↑ University of Maryland “Minorities at Risk” Project. Assessment for Christians in Iran. Page dated 31 December 2006. Assessed on 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Miller, Duane Alexander (October 2009). "The Conversion Narrative of Samira: From Shi'a Islam to Mary, her Church, and her Son". St Francis Magazine 5 (5): 81–92.

- ↑ Miller, Duane Alexander (April 2012). "The Secret World of God: Aesthetics, Relationships, and the Conversion of ‘Frances’ from Shi’a Islam to Christianity". Global Missiology 9 (3).

- ↑ Nasser, David (2009). Jumping through Fires. Grand Rapids: Baker.

- ↑ Rabiipour, Saiid (2009). Farewell to Islam. Xulon.

- ↑ korpu.net

- ↑ گیلک مدیا – فیلم و صوت به زبان گیلکی

- ↑ Bakhtiari Jesus Film

- ↑ Luri Jesus Film

| |||||||||||