Christian symbolism

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Christian symbolism is the use of symbols, including archetypes, acts, artwork or events, by Christianity. It invests objects or actions with an inner meaning expressing Christian ideas.

The symbolism of the early Church was characterized by being understood by initiates only,[1] while after the legalization of Christianity in the 4th-century more recognizable symbols entered in use. Christianity has borrowed from the common stock of significant symbols known to most periods and to all regions of the world.[2]

Christianity has not generally practised Aniconism, or the avoidance or prohibition of types of images, even if the early Jewish Christians sects, as well as some modern denominations, preferred to some extent not to use figures in their symbols, by invoking the Decalogue's prohibition of idolatry.

Early Christian symbols

Cross and crucifix

The cross, which is today one of the most widely recognised symbols in the world, was used as a symbol from the earliest times. This is indicated in the anti-Christian arguments cited in the Octavius of Minucius Felix, chapters IX and XXIX, written at the end of the 2. century (cited as AD 197) or the beginning of the next,[3][4]

By the early 3rd century the cross had become so closely associated with Christ that Clement of Alexandria, who died between 211 and 216, could without fear of ambiguity use the phrase τὸ κυριακὸν σημεῖον (the Lord's sign) to mean the cross, when he repeated the idea, current as early as the Epistle of Barnabas, that the number 318 (in Greek numerals, ΤΙΗ) in Genesis 14:14 was a foreshadowing (a "type") of the cross (T, an upright with crossbar, standing for 300) and of Jesus (ΙΗ, the first two letters of his name ΙΗΣΟΥΣ, standing for 18).[5]

His contemporary Tertullian could designate the body of Christian believers as crucis religiosi, i.e. "devotees of the Cross".[6] In his book De Corona, written in 204, Tertullian tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace repeatedly on their foreheads the sign of the cross.[7]

The Jewish Encyclopedia states:

The cross as a Christian symbol or "seal" came into use at least as early as the second century (see "Apost. Const." iii. 17; Epistle of Barnabas, xi.-xii.; Justin, "Apologia," i. 55-60; "Dial. cum Tryph." 85-97); and the marking of a cross upon the forehead and the chest was regarded as a talisman against the powers of demons (Tertullian, "De Corona," iii.; Cyprian, "Testimonies," xi. 21-22; Lactantius, "Divinæ Institutiones," iv. 27, and elsewhere). Accordingly the Christian Fathers had to defend themselves, as early as the second century, against the charge of being worshipers of the cross, as may be learned from Tertullian, "Apologia," xii., xvii., and Minucius Felix, "Octavius," xxix. Christians used to swear by the power of the cross.[8][9]

Although the cross was known to the early Christians, the crucifix did not appear in use until the 5th century.[10] French Medievalist scholar and historian of ideas M.-M. Davy has described in great details Romanesque Symbolism as it developed in the Middle Ages in Western Europe.[11]

Ichthys

Among the symbols employed by the early Christians, that of the fish seems to have ranked first in importance. Its popularity among Christians was due principally to the famous acrostic consisting of the initial letters of five Greek words forming the word for fish (Ichthus), which words briefly but clearly described the character of Christ and the claim to worship of believers: "Ἰησοῦς Χριστὸς Θεοῦ Υἱὸς Σωτήρ", (Iēsous Christos Theou Hyios Sōtēr), meaning, Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour.[12] This explanation is given among others by Augustine in his Civitate Dei,[13] where he also notes that the generating sentence "Ίησοῦς Χρειστὸς [sic] Θεοῦ Υἱὸς Σωτήρ" has 27 letters, i.e. 3 x 3 x 3, which in that age indicated power.

Alpha and Omega

The use since the earliest Christianity of the first and the last letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha (α or Α) and omega (ω or Ω), derives from the statement said by Jesus (or God) himself "I am Alpha and Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End" (Revelation 22:13, also 1:8 and 21:6).

Staurogram _I_193_2.jpg)

The Staurogram (meaning monogram of the cross, from the Greek σταυρός, i.e. cross), or Monogrammatic Cross or Tau-Rho symbol, is composed by a tau (Τ) superimposed on a rho (Ρ). The Staurogram was first used to abbreviate the Greek word for cross in very early New Testament manuscripts such as P66, P45 and P75, almost like a nomen sacrum.[14]

Ephrem the Syrian in the 4th-century explained these two united letters stating that the tau refers to the cross, and the rho refers to the Greek word "help" (Βoήθια [sic]; proper spelling: Βoήθεια) which has the numerological value in Greek of 100 as the letter rho has. In such a way the symbol expresses the idea that the Cross saves.[14] The two letters tau and rho can also be found separately as symbols on early Christian ossuaries.[15]

The tau was considered a symbol of salvation due to the identification of the tau with the sign which in Ezechiel 9:4 was marked on the forehead of the saved ones, or due to the tau-shaped outstretched hands of Moses in Exodus 17:11.[14] The rho by itself can refer to Christ as Messiah because Abraham, taken as symbol of the Messiah, generated Isaac according to a promise made by God when he was one hundred years old, and 100 is the value of rho.[15]:158

The Monogrammatic Cross was later seen also as a variation of the Chi Rho symbol, and it spread over Western Europe in the 5th and 6th-century.[16]

Chi Rho _I_193_1.jpg)

The Chi Rho is formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters chi and rho (ΧΡ) of the Greek word "ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ" =Christ in such a way to produce the monogram. Widespread in ancient Christianity, it was the symbol used by the Roman emperor Constantine I as vexillum (named Labarum).

IH Monogram

The initials of the name of Jesus in Greek, iota (Ι) and eta (Η), sometime superimposed one on the other, or the numeric value 18 of ΙΗ in Greek, was a well known and very early way to represent Christ.[17] This symbol was already explained in the Epistle of Barnabas and by Clement of Alexandria.[5] For other christograms such as IHS, see Article Christogram.

IX Monogram _I_193_4.jpg)

An early form of the monogram of Christ, found in early Christian ossuaries in Palestinia, was formed by superimposing the first (capital) letters of the Greek words for Jesus and Christ, i.e. iota Ι and chi Χ, so that this monogram means "Jesus Christ".[15]:166 Another more complicated explanation of this monogram was given by Ireneaus[18] and Pachomius: because the numeric value of iota is 10 and the chi is the initial of the word "Christ" (Greek: ΧΡΕΙΣΤΟΣ [sic]; proper spelling: ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ) which has 8 letters, these early fathers calculate 888 ((10*8)*10)+((10*8)+8) which was a number already known to represent Jesus, being the sum of the value of the letters of the name "Jesus" (IHΣΟΥΣ) (10+8+200+70+400+200).[15]:169–170

Other Christian symbols

The Good Shepherd

The image of the Good Shepherd, often with a sheep on his shoulders, is the most common of the symbolic representations of Christ found the Catacombs of Rome, and it is related to the Parable of the Lost Sheep. Initially it was also understood as a symbol like others used in Early Christian art. By about the 5th century the figure more often took on the appearance of the conventional depiction of Christ, as it had developed by this time, and was given a halo and rich robes.

Dove

The dove as a Christian symbol is of very frequent occurrence in ancient ecclesiastical art.[19] According to Matthew 3:16, during the Baptism of Jesus the Holy Spirit descended like a dove and came to rest on Jesus. For this reason the dove became a symbol of the Holy Spirit and in general it occurs frequently in connection with early representations of baptism. It signifies also the Christian soul, not the human soul as such, but as indwelt by the Holy Spirit; especially, therefore, as freed from the toils of the flesh and entered into rest and glory.[2] The Peristerium or Eucharistic dove was often used in the past, and sometime still used in Eastern Christianity, as Church tabernacle.

However the more ancient explanation of the dove as a Christian symbol refers to it as a symbol of Christ: Ireneaus[20] in the 2nd-century explains that the number 801 is both the numerological value of the sum in Greek of the letters of the word "dove" (Greek: περιστερά) and the sum of the values of the letters Alpha and Omega, which refers to Christ. In the Bible story of Noah and the Flood, after the flood a dove returns to Noah bringing an olive branch as a sign that the water had receded, and this scene recalled to the Church Fathers Christ who brings salvation through the cross. This biblical scene led to interpreting the dove also as a symbol of peace.

Peacock

Ancient people believed that the flesh of a peafowl did not decay after death, and it so became a symbol of immortality. This symbolism was adopted by early Christianity, and thus many early Christian paintings and mosaics show the peacock. The peacock is still used in the Easter season especially in the east.[21]

Pelican

In medieval Europe, the pelican was thought to be particularly attentive to her young, to the point of providing her own blood by wounding her own breast when no other food was available. As a result, the pelican became a symbol of the Passion of Jesus and of the Eucharist since about the twelfth century.[22]

Anchor

The Christians adopted the anchor as a symbol of hope in future existence because the anchor was regarded in ancient times as a symbol of safety. For Christians, Christ is the unfailing hope of all who believe in him: Saint Peter, Saint Paul, and several of the early Church Fathers speak in this sense. The Epistle to the Hebrews 6:19-20 for the first time connects the idea of hope with the symbol of the anchor.[23]

A fragment of inscription discovered in the catacomb of St. Domitilla contains the anchor, and dates from the end of the first century. During the second and third centuries the anchor occurs frequently in the epitaphs of the catacombs. The most common form of anchor found in early Christian images was that in which one extremity terminates in a ring adjoining the cross-bar while the other ends in two curved branches or an arrowhead; There are, however, many deviations from this form.[23] In general the anchor can symbolize hope, steadfastness, calm and composure.[24]

Elemental symbols

Elemental symbols were widely used by the early Church. Water has specific symbolic significance for Christians. Outside of baptism, water may represent cleansing or purity. Fire, especially in the form of a candle flame, represents both the Holy Spirit and light. The sources of these symbols derive from the Bible; for example from the tongues of fire that symbolized the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, and from Jesus' description of his followers as the light of the world; or God is a consuming fire found in Hebrews 12.[10]

Lily crucifix

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lily Crucifix. |

A lily crucifix is a rare symbol of Anglican churches in England. It depicts Christ crucified on a lily, or holding such a plant. The symbolism may be from the medieval belief that the Annunciation of Christ and his crucifixion occurred on the same day of the year, March 25.[25]

There are few depictions of a lily crucifix in England. One of the most notable is a painting on a wall above the altar at All Saint's Church, Godshill, Isle of Wight. Other examples include:

- An alabaster example on a tomb in St Mary's Church, Nottingham.

- The Lady Chapel of St Helen's, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, has a wall painting.

- Five examples are in glass as at Holy Trinity Church, Long Melford.

- At All Saints, Great Glemham, Suffolk, the image is on the base of a font.

- At St Mary, Binham, Norfolk, an image in a bench end may be a lily crucifix.

- In Tong, Shropshire, St. Bartholomew's choir stall No. 8 depicts a lily crucifix.

- The Church of St John the Baptist, Wellington includes a Lily crucifix in the carving of the centre mullion of the east window of the Lady chapel.[26]

Others

- Christian flag

- Cross and Crown

- IHS (monogram)

- INRI

- Lamb

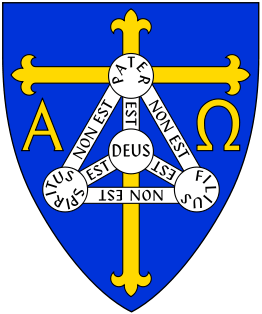

- Shield of the Trinity (or Scutum Fidei)

- Trefoil

- Triquetra

Tomb paintings

Christians from the very beginning adorned their catacombs with paintings of Christ, of the saints, of scenes from the Bible and allegorical groups. The catacombs are the cradle of all Christian art.[27] Early Christians accepted the art of their time and used it, as well as a poor and persecuted community could, to express their religious ideas.[27]

From the second half of the 1st century to the time of Constantine the Great they buried their dead and celebrated their rites in these underground chambers. The Christian tombs were ornamented with indifferent or symbolic designs—palms, peacocks, with the chi-rho monogram, with bas-reliefs of Christ as the Good Shepherd, or seated between figures of saints, and sometimes with elaborate scenes from the New Testament.[27]

Other Christian symbols include the dove (symbolic of the Holy Spirit), the sacrificial lamb (symbolic of Christ's sacrifice), the vine (symbolizing the necessary connectedness of the Christian with Christ) and many others. These all derive from the writings found in the New Testament.[10] Other decorations that were common included garlands, ribands, stars landscapes, which had symbolic meanings, as well.[27]

Symbols of Christian Churches

Sacraments

Some of the oldest symbols in the Christian church are the sacraments, the number of which vary between denominations. Always included are Eucharist and baptism. The others which may or may not be included are ordination, unction, confirmation, penance and marriage. They are together commonly described as an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace or, as in the Roman Catholic system, "outward signs and media of grace."[28]

At the very least, the rite is seen as a symbol of the spiritual change or event that takes place. In the Eucharist, the bread and wine are, at the least, symbolic of the broken body and shed blood of Jesus, and in Roman Catholicism, become the actual Body of Christ and Blood of Christ through Transubstantiation, which in turn represent salvation brought to the recipient by the death of Jesus.[28]

The rite of baptism is, at the least, symbolic of the cleansing of the sinner by God, and, especially where baptism is by immersion, of the spiritual death and resurrection of the baptized person. Opinion differs as to the symbolic nature of the sacraments, with some Protestant denominations considering them entirely symbolic, and Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Lutherans, and some Reformed Christians believing that the outward rites truly do, by the power of God, act as media of grace.[28]

Icons

The tomb paintings of the early Christians led to the development of icons. An icon is an image, picture, or representation; it is likeness that has symbolic meaning for an object by signifying or representing it, or by analogy, as in semiotics. The use of icons, however, was never without opposition. It was recorded that, "there is no century between the fourth and the eighth in which there is not some evidence of opposition to images even within the Church.[29] Nonetheless, popular favor for icons guaranteed their continued existence, while no systematic apologia for or against icons, or doctrinal authorization or condemnation of icons yet existed.

Though significant in the history of religious doctrine, the Byzantine controversy over images is not seen as of primary importance in Byzantine history. "Few historians still hold it to have been the greatest issue of the period..."[30]

The Byzantine Iconoclasm began when images were banned by Emperor Leo III the Isaurian sometime between 726 and 730. Under his son Constantine V, a council forbidding image veneration was held at Hieria[31] near Constantinople in 754. Image veneration was later reinstated by the Empress Regent Irene, under whom another council was held reversing the decisions of the previous iconoclast council and taking its title as Seventh Ecumenical Council. The council anathematized all who held to iconoclasm, i.e. those who held that veneration of images constitutes idolatry. Then the ban was enforced again by Leo V in 815. And finally icon veneration was decisively restored by Empress Regent Theodora.

Today icons are used particularly among Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Assyrian and Eastern Catholic Churches.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christian symbols. |

See also

- Christian art

- Christian cross

- Holy Spirit in Christian art

- Peace symbols

- Religious symbolism

- Saint symbology

- Sator Square

- Symbols and symbolism in Christian demonology

- The Wordless Book

- Bestiaries

- Aniconism in Christianity

References

- ↑ Jenner, Henry (1910). Christian Symbolism. Plymouth. p. xiv.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1

Herbert Thurston (1913). "Symbolism". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbert Thurston (1913). "Symbolism". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ ANF04. Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second | Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- ↑ Minucius Felix speaks of the cross of Jesus in its familiar form, likening it to objects with a crossbeam or to a man with arms outstretched in prayer (Octavius of Minucius Felix, chapter XXIX).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Stromata, book VI, chapter XI

- ↑ Apology., chapter xvi. In this chapter and elsewhere in the same book, Tertullian clearly distinguishes between a cross and a stake.

- ↑ "At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign" (De Corona, chapter 3)

- ↑ see Apocalypse of Mary, viii., in James, "Texts and Studies," iii. 118

- ↑ JewishEncyclopedia.com - CROSS:

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Dilasser, Maurice. The Symbols of the Church (1999). Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, hardcover: ISBN 0-8146-2538-X

- ↑ M.-M. Davy, Initiation à la Symbolique Romane. New edition. Paris: Flammarion, 1977.

- ↑

Maurice Hassett (1913). "Symbolism of the Fish". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Maurice Hassett (1913). "Symbolism of the Fish". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Augustine.

The City of God. Wikisource. XVIII, 23.

The City of God. Wikisource. XVIII, 23. - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Hutado, Larry (2006). "The staurogram in early Christian manuscripts: the earliest visual reference to the crucified Jesus?". In Kraus, Thomas. New Testament Manuscripts. Leiden: Brill. pp. 207–26. ISBN 978-90-04-14945-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Bagatti, Bellarmino (1984). The church from the circumcision: history and archaeology of the Judaeo-Christians. Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Collectio Minor, n.2. Jerusalem.

- ↑ Redknap, FirstName (1991). The Christian Celts : treasures of late Celtic Wales. Cardiff: National Museum of Wales. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7200-0354-3.

- ↑ Hurtado, Larry (2006). The earliest Christian artifacts : manuscripts and Christian origins. William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0-8028-2895-8.

- ↑ Ireneaus, Adv Haer, 1.15.2

- ↑

Arthur Barnes (1913). "Dove". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Arthur Barnes (1913). "Dove". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Ireneaus, Adv Haer, 1.15.6

- ↑ "Birds, symbolic." Peter and Linda Murray, Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art (2004).

- ↑ Jenner, Henry (2004) [1910]. Christian Symbolism. Kessinger Publishing. p. 37.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1

Maurice Hassett (1913). "The Anchor (as Symbol)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Maurice Hassett (1913). "The Anchor (as Symbol)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Klöpping, Laura (2012). Customs, Habits and Symbols of the Protestant Religion. GRIN Verlag. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-656-13453-4.

- ↑ The Passion in Art. Richard Harries. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004

- ↑ "St John the Baptist, Wellington". Wellington and District Team Ministry. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Fortescue, Adrian (1912). "Veneration of Images". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Kennedy, D.J (1912). "Sacraments". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ↑ Ernst Kitzinger, The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm, Dumbarton Oaks, 1954, quoted by Pelikan, Jaroslav; The Spirit of Eastern Christendom 600-1700, University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- ↑ Patricia Karlin-Hayter, Oxford History of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, 2002.

- ↑ See Council of Hieria.

External links

- Symbols in Christian Art and Architecture Comprehensive general listing.

- Christian Symbols Net Very comprehensive site, complete with search engine.

- Christian Symbols and Glossary (keyword searchable, includes symbols of saints)

- ReligionFacts.com: Christian Symbols Basic Christian symbols A to T, types of crosses, number symbolism and color symbolism.

- Meaning of Colors for Flags Biblical meanings of color used for Christian worship flags.

- Color Symbolism in The Bible An in depth study on symbolic color occurrence in The Bible.

- Christian Symbol Wood Carvings Forty symbols at Kansas Wesleyan University

- Old Christian Symbols from book by Rudolf Koch

- Christian Symbols, Origins and Meanings

- Tree of Jesse Directory by Malcolm Low.

- Chrismon Templates Symbol outlines that can be used to create Christian themed projects

- Christian Symbols and Variations of Crosses - Images and Meanings

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||