Christian archaeology

Christian Archeology (more commonly termed "Biblical Archaeology") is the study of archaeological sites in connection to the texts of the Bible. The abundance of forgeries, fakes, and misinterpretations is rife, and as such the verification of context and the maintenance of an unbiased standpoint is essential. It is an auxiliary of history and has played an important role in the quest for the historical Jesus and an attempt to establish the historicity of Christ.[1]

Pool of Bethesda

According to the Gospel of John, the Pool of Bethesda was a swimming bath (Greek: kolumbethra) with five porticos (translated as porches by older English bible translations).[2][3] The Johannine narrative describes the porticos as being a place in which large numbers of infirm people were waiting, which corresponds well with the site's 1st century CE use as an asclepieion. The biblical narrative describes a Shabbat visit to the site by Jesus, during which he heals a man who has been bedridden for many years, and could not make his own way into the pool.[4] Prior to archaeological digs, the Pool of Bethesda was identified with the modern so-called Fountain of the Virgin, in the Kidron Valley, not far from the Pool of Siloam, and alternately with the Birket Israel, a pool near the mouth of the valley which runs into the Kidron south of St. Stephen's Gate.

In digs conducted in the 19th century, Schick discovered a large tank situated about 100 feet north-west of St. Anne's Church, which he contended was the Pool of Bethesda. Further archaeological excavation in the area, in 1964, discovered the remains of the Byzantine and Crusader churches, Hadrian's Temple of Asclepius and Serapis, the small healing pools of the Asclepieion, the other of the two large pools, and the dam between them.[5] It was discovered that the Byzantine construction was built in the very heart of Hadrian's construction, and contained the healing pools.[5][6]

This archaeological discovery proved beyond a doubt that the description of this pool in the Gospel of John was not the creation of the Evangelist, but instead reflected an accurate and detailed knowledge of the site. The Gospel speaks of the name of the pool as Bethesda, its location near the Sheep Gate; and the fact that it has five porticos; with rushing water. These details are corroborated through literary and archaeological evidence affirming the historical accuracy of the Johannine account.[7]

Caiaphas ossuary

Adherents of the Jesus myth theory argued in favour of Caiaphas's historicity.[8] In 1990, an ornate limestone ossuary was discovered in the Abu Tor neighborhood of modern Jerusalem.[9][10]

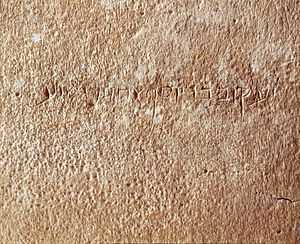

This ossuary appeared authentic and contained human remains. The Aramaic inscription on the side which read "Joseph son of Caiaphas." also appeared authentic. The bones in the ossuary were of an elderly man. According to the New York Times and a number of Biblical scholars, if the remains are proven to be those of Caiaphas, it will be an important confirmation of the New Testament account, and lead to greater understanding of the historical Jesus.

If true, the discovery would be an important confirmation of a significant segment of the New Testament account of Jesus leading to a greater understanding of the historical Jesus.[9][10][11]

Since the original discovery, the identification with Caiaphas has been challenged by some scholars on various grounds, including the spelling of the inscription, the lack of any mention of Caiaphas's status as High Priest, the plainness of the tomb (although the ossuary itself is as ornate as might be expected from someone of his rank and family), and other reasons.[12][13]

Pilate Stone

The Pilate Stone is the name given to a block of limestone with a carved inscription attributed to Pontius Pilate, a prefect of the Roman-controlled province of Judaea from 26-36. The stone was found in 1961 by a team of Italian archeologists and is significant because this is the only universally accepted archaeological find with an inscription mentioning the name "Pontius Pilatus" to date.

The 82 cm x 65 cm limestone block, was found in 1961 in an excavation of an ancient theater (built by decree of Herod the Great c. 30 BC), called Caesarea Maritima in the present-day city of Caesarea-on-the-Sea (also called Maritima). On the partially damaged block is a dedication to Tiberius Caesar Augustus. It has been deemed authentic because it was discovered in the coastal town of Caesarea, which was the capital of Iudaea Province[14] during the time Pontius Pilate was Roman governor.

The partial inscription reads (conjectural letters in brackets):

- [DIS AUGUSTI]S TIBERIEUM

- [PO]NTIUS PILATUS

- [PRAEF]ECTUS IUDA[EA]E

- [FECIT D]E[DICAVIT]

The translation from Latin to English for the inscription reads: Pontius Pilate, prefect of Judea, has restored the Tiberieum of the Seaman (or possibly, of the Caesareans) .[15]

James Ossuary

The James ossuary was on display at the Royal Ontario Museum from November 15, 2002 to January 5, 2003. |

Close-up of the Aramaic inscription: “Ya'akov bar Yosef akhui di Yeshua” (“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”) |

The James Ossuary is a 2,000-year old limestone box used as a container for the bones of the deceased. Antiquities dealer Oded Golan is believed to have discovered the James Ossuary at some point before 2003 on the illegal Israeli antiquities market. The Aramaic inscription on the artifact reads: Ya'akov bar-Yosef akhui diYeshua, "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus."

References

- ↑ Charles Wesley Bennett, Christian archaeology, Volume 4, Phillips & Hunt, 1888. p 13

- ↑ John 5:2

- ↑ Peake's commentary on the Bible (1962), on John 5:1-18

- ↑ John 5:1-18

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 [http://www.christusrex.org/www1/ofm/sbf/escurs/Ger/10quadroBig.jpg/> An archaeological diagram of the layout - the diagram displayed at the location itself - is visible at this link]

- ↑ James H. Charlesworth 2006. p 560-566

- ↑ James H. Charlesworth, Jesus and archaeology, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2006. p 566

- ↑ "And Caiaphas is an historic personality, known and named as such by Flavius Josephus, which cannot be said of Jesus, as the forged passage in the "Antiquities of the Jews" (18:63) long ago has been recognized as such by even the most conservative students." Georg Brandes, Jesus: A Myth, trans. Edwin Björkman (New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1926), p. 46.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The Caiaphas Ossuary Great archaeology, 2010. p 1

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Tomb May Hold the Bones Of Priest Who Judged Jesus"

- ↑ James H. Charlesworth, Jesus and archaeology, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2006. pp 323-329

- ↑ James H. Charlesworth 2006. pp 323-329

- ↑ Bond, Helen Katharine (2004). Caiaphas: friend of Rome and judge of Jesus?. Westminster/John Knox Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-664-22332-8.

- ↑ A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben-Sasson editor, 1976, page 247: "When Judea was converted into a Roman province [in 6 CE, page 246], Jerusalem ceased to be the administrative capital of the country. The Romans moved the governmental residence and military headquarters to Caesarea. The centre of government was thus removed from Jerusalem, and the administration became increasingly based on inhabitants of the hellenistic cities (Sebaste, Caesarea and others)."

- ↑ Craig A. Evans, The Bible knowledge background commentary, Volume 3, Cook Publishing, 2005. p 151

Further reading

- Halevi, Masha, "Between Faith and Science: Franciscan Archaeology in the Service of the Holy Places", Middle Eastern Studies,Volume 48,Issue 2, 2012, pp. 249-267.

- Ashmore, W. and Sharer, R. J., Discovering Our Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7674-1196-X. This has also been used as a source.

- Neumann, Thomas W. and Robert M. Sanford, Practicing Archaeology: A Training Manual for Cultural Resources Archaeology Rowman and Littlefield Pub Inc, August, 2001, hardcover, 450 pages, ISBN 0-7591-0094-2

- Renfrew, Colin & Bahn, Paul G., Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice, Thames and Hudson, 4th edition, 2004. ISBN 0-500-28441-5

- Sanford, Robert M. and Thomas W. Neumann, Cultural Resources Archaeology: An Introduction, Rowman and Littlefield Pub Inc, December, 2001, trade paperback, 256 pages, ISBN 0-7591-0095-0

- Trigger, Bruce. 1990. "A History of Archaeological Thought". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33818-2

- Frend, William Hugh Clifford, The Archaeology of Early Christianity. A History, Geoffrey Chapman, 1997. ISBN 0-225-66850-5

External links

- Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana.

- Excavation Sites Archaeological work and volunteer pages.

- Archaeology in Popular Culture

- Anthropology Resources on the Internet - Anthropology Resources on the Internet : a web directory with over 3000 links grouped in specialised topics.

- Archaeology magazine published by the Archaeological Institute of America

- Archaeology Directory - Directory of archaeological topics on the web.

- The 2003- Iraq War & Archaeology Information about looting in Iraq.

-

"Christian Archaeology". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Christian Archaeology". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.