Chinese city wall

Chinese city walls (traditional Chinese: 城牆; simplified Chinese: 城墙; pinyin: chéngqiáng; literally: "city wall") refer to civic defensive systems used to protect towns and cities in China in pre-modern times. The system consisted of walls, towers, and gates, which were often built to a uniform standard throughout the Empire.

Meaning of the word Chengqiang

The Chinese word Chéngqiáng (城墙) can be used in two senses in the modern Chinese language. In a broad sense, it means all defensive walls, including the Great Wall of China, as well as similar structures in other countries such as Hadrian's Wall. In a narrow sense, Chengqiang specifically refers to defensive walls built around a city or town.

In classical Chinese, the character Chéng (城) denoted the defensive wall of the "inner city", housing government buildings. The character Guó (郭) denoted the defensive wall of the "outer city", housing mainly residences. The phrase Chángchéng (长城), literally "the Long Wall", specifically referred to the Great Wall.

History

Like various other innovations in Chinese history, the invention of the city wall is attributed to a semi-mythological sage; in this case, to Xia Dynasty leader Gun (鲧), the father of Yu the Great.[1] It is said that Gun built the inner wall (城) to defend the prince, and the outer wall (郭) to settle the people. An alternative theory attributes the first city wall to the Yellow Emperor.[2] A number of neolithic-period walls surrounding substantial settlements have been excavated in recent years. These include a supposed wall at a Liangzhu culture site, a stone wall at Sanxingdui, and several tamped earth walls at the Longshan culture site.[3][4] These walls generally protected settlements the size of a large village.

In Shang Dynasty China, at the site of Ao, large walls were erected in the 15th century BC that had dimensions of 20 meters / 65 feet in width at the base and enclosed an area of some 2,100 yards (1,900 m) squared.[5] In similar dimensions, the ancient capital of the State of Zhao, Handan (founded in 386 BC), had walls that were again 20 meters / 65 feet wide at the base, a height of 15 meters / 50 feet tall, with two separate sides of its rectangular enclosure measured at a length of 1,530 yards (1,400 m).[5]

Most towns of a significant size possessed a city wall from the Zhou Dynasty onwards. For example, the city wall of Pingyao were first constructed between 827 BC and 782 BC, in the reign of King Xuan of Zhou. The city wall of Suzhou followed, prior to their demolition in the 1960s and 1970s, largely the same plan as set down by Wu Zixu in the 5th century BC. By the Yuan Dynasty, it was government policy that towns which were administrative seats of county-level units or above were to have defensive walls. In ancient China, sieges of city walls (along with naval battles) were portrayed on bronze 'hu' vessels dated to the Warring States (5th century BC to 3rd century BC), like those found in Chengdu, Sichuan, China in 1965.[6]

The construction of city walls grew to a peak in the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty. Sophisticated construction techniques meant that major city walls, such as that in the capitals Beijing and Nanjing, were specifically built to withstand cannon fire. However, with the advent of modern Western firearms, traditional fortifications began to lose their defensive functions in the 19th and 20th centuries. The traditional city wall also proved an obstacle to efficient trade and intercourse. For example, the city wall of Shanghai, built to repel Wokou raiders in the Ming dynasty, was almost completely demolished after the Xinhai Revolution at the request of the city's merchant community.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, a political dimension was added to the economic problem posed by city walls. In Beijing, for example, the proposed demolition of the city walls was at first opposed by experts ranging from architect Liang Sicheng, to Soviet advisor Mosin, on the grounds that the city walls of Beijing were the most sophisticated and well-preserved system of city walls in China. However, in 1958 Mao Zedong intervened, and declared that the demolition of the old city wall was a political issue. Despite mayor Peng Zhen's efforts to preserve gates and towers, by 1970 almost all of the city wall had been demolished.

Composition

Many Chinese cities were deliberately sited and planned. City walls, when not constrained by geography, tend to be rectangular or square. Philosophical and even feng shui considerations were adopted in siting gates and towers, and the walled city itself.

Chinese cities rarely centre on a castle. Instead, the city's administrative centre is spread over a relatively large area, which may or may not be surrounded by a second set of "inner" walls similar in shape and construction to the main, outer wall.

Long-term strategic considerations adopted in the planning process also meant that the walls of important cities often enclosed an area much larger than the existing urban areas, both in order to ensure excess capacity for growth, and to secure resources such as timber and farmland in times of war. Thus, for example, the city wall of Quanzhou in Fujian still contained one quarter vacant land by 1945. The city wall of Suzhou by the Republic of China era still contained large tracts of farmland.[7] The City Wall of Nanjing, built in the Ming Dynasty, enclosed an area large enough to house an airport, bamboo forests, and lakes in modern times.[8]

Several features are typical of most Chinese city walls.

Shape

Where allowed by geography, Chinese city walls are rectangular in shape, with four orthogonal walls. Some wall systems are composed of a number of such rectangles, set adjacent to or concentrically within each other. For example, the city wall of Beijing is composed of four rectangles: a wider outer city to the south, a narrower inner city to the north, an imperial city within the inner city, and the Forbidden City at the centre of that.

The walls could be constructed of a variety of materials. Common materials included rammed earth, compressed earth blocks, brick, stone, and any combination of these. In its standardised form during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the wall was composed of a core made of compressed earth and mixed debris, strengthened by various binders. The wall was then surfaced with bricks. It was topped with crenellations facing out, and a parapet facing in.

Gates

Gates were placed symmetrically along the walls. The principal gate was traditionally located at the centre of the south wall. Gatehouses were generally built of wood and brick, which sat atop a raised and expanded section of the wall, surrounded by crenellated battlements. A tunnel ran under the gatehouse, with several metal grates and wooden doors. Camouflaged defensive positions are placed along the tunnel (in an effect similar to murder holes). Gatehouses were accessed by ramps, called horse ramps or bridle paths[9] , (Chinese: 马道; pinyin: mǎdào), which sat against the wall adjacent to the gate.

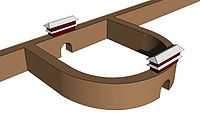

Barbican

An "archery tower" was often placed in front of the main gatehouse, forming a barbican (Chinese: 瓮城; pinyin: wèngchéng). In its final form during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the archery tower was an elaborate construction, of comparable height to the main gatehouse, which stands some distance in front of the main gatehouse. At its base was a gate. The archery tower is so-named because of its rows of archery (and later cannon) placements, from which defenders could fire projectiles on attackers. Auxiliary walls, running perpendicularly to the main wall, connect the archery tower with the main gatehouse, enclosing a rectangular area. This area serves as a buffer zone, should the first gate be breached. Its Chinese name, "jar walls", refers to the intended strategy whereby attackers coming through the archery tower would be trapped in the barbican, open to attack from all sides.

In large gates there may be multiple barbicans - the main gate of Nanjing (Gate of China, Nanjing) had three barbicans, forming the most elaborate system still in existence in China.

Towers

Towers that protruded from the wall were located at regular intervals along the wall. Large and elaborate towers, called corner towers (角楼), were placed where two walls joined (i.e. at corners). These were significantly higher than the wall itself, and gave defenders a bird's eye view over both the city and its surroundings.

Moat

In larger cities, a moat surrounded the wall. This could be connected to canals or rivers both in the city and outside, thus providing both a defense and a convenient transportation route. Nearby waterways might be adopted or altered to connect to, or form part of, the moat.

Extant city walls

As the last imperial capital of China, the city walls of Beijing survived in substantially complete form into the 1950s, but, apart from the Forbidden City whose walls remains well-preserved, city walls from the Ming Dynasty have suffered wholesale demolition in the decades since. Only Qianmen's gate and arrow tower, Deshengmen's arrow tower, a section of the wall and Southeast Corner Tower preserved in the Ming City Wall Relics Park, and the Xibianmen corner tower have survived. The Yongdingmen Gate was rebuilt in 2005.

Of the walls of other major historical cities, those of Nanjing, Xi'an and Kaifeng are notable for their state of preservation. The walls of Nanjing and Xi'an are Ming Dynasty originals with extensive Qing Dynasty and modern restorations, while the wall of Kaifeng visible today is largely the result of Qing Dynasty restoration.

The walls of some smaller cities and towns have survived more or less intact. These include the walls of Pingyao in Shanxi, Dali in Yunnan, Jingzhou in Hubei, and Xingcheng in Liaoning. Smaller garrison towns or fortifications include Fishing Town near Chongqing, Wanping county fortifications near Marco Polo Bridge in Beijing, the garrison town of Shanhai Pass, and Qiansuo in Huludao, Liaoning.

Isolated remnants and some modern recreations can be seen today in many other cities. The walls of Luoyang in Henan survive as heavily eroded remains. The surviving walls of Shangqiu in Henan, while extensive, have heavily deteriorated over time. Only small parts of the city walls protecting the Confucian compound in Qufu are authentic, the rest having been demolished in 1978 and rebuilt in recent years. Some isolated gates of Hangzhou and Suzhou (especially Panmen Gate) have either survived or been rebuilt. Substantial remains of the gates of Zhengding in Hebei have survived but the walls have largely been stripped to their earthen core. One small section of the city wall of Shanghai is visible today.

Notes

- ↑ Spring and Autumn of Wu and Yue (吴越春秋). Nanjing: Jiangsu Ancient Books Press. 1986

- ↑ "Biography of Xuanyuan" (轩辕本纪). in Sima Qian. Shiji. Beijing: Zhonghua Publishing. 2005. ISBN 7-101-00304-4

- ↑ 史前城址与中原地区中国古代文明中心地位的形成

- ↑ 良渚文化网

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 43.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 5, Part 6, 446.

- ↑ Chen Zhengxiang (陈正祥). Chinese Cultural Geography (《中国文化地理》),Joint Publishing, Beijing 1983, pp 68, 74

- ↑ Ray Huang. China: a Macro History. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1988. ISBN 0-87332-452-8

- ↑ Yu, Zhuoyun (1984). Palaces of the Forbidden City. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-53721-7.

References

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 6. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

Further reading

- Wheatley, Paul, The Pivot of the Four Quarters (Edinburgh U. Press, 1971)

External links

- (Chinese) Comparative City History Research, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and Osaka City University

- Nanjing Zhonghua (China) Gate