Chemical milling

Chemical milling or industrial etching is the subtractive manufacturing process of using baths of temperature-regulated etching chemicals to remove material to create an object with the desired shape.[1][2] It is mostly used on metals, though other materials are increasingly important. It was developed from armor-decorating and printing etching processes developed during the Renaissance as alternatives to engraving on metal. The process essentially involves bathing the cutting areas in a corrosive chemical known as an etchant, which reacts with the material in the area to be cut and causes the solid material to be dissolved; inert substances known as maskants are used to etch specific areas of the material.[2][3]

History

Organic chemicals such as lactic acid and citric acid have been used to etch metals and create products as early as 400 BCE, when vinegar was used to corrode lead and create the pigment ceruse, also known as white lead.[4] Most modern chemical milling methods involve alkaline etchants; these may have been used as early as the first century CE.

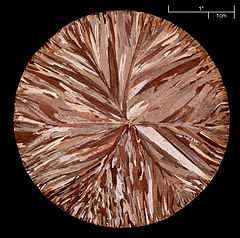

Armor etching, using strong mineral acids, was not developed until the fifteenth century. Etchants mixed from salt, charcoal, and vinegar were applied to plate armor that had been painted with a maskant of linseed-oil paint. The etchant would bite into the unprotected areas, causing the painted areas to be raised into relief.[4] Etching in this manner allowed armor to be decorated as if with precise engraving, but without the existence of raised burrs; it also prevented the necessity of the armor being softer than an engraving tool.[5] Late in the seventeenth century, etching became used to produce the graduations on measuring instruments; the thinness of lines that etching could produce allowed for the production of more precise and accurate instruments than were possible before.[6] Not long after, it became used to etch trajectory information plates for cannon and artillery operators; paper would rarely survive the rigors of combat, but an etched plate could be quite durable. Often such information (normally ranging marks) was etched onto equipment such as stiletto daggers or shovels.

In 1782, the discovery was made by John Senebier that certain resins lost their solubility to turpentine when exposed to light; that is, they hardened. This allowed the development of photochemical milling, where a liquid maskant is applied to the entire surface of a material, and the outline of the area to be masked created by exposing it to UV light.[7] Photo-chemical milling was extensively used in the development of photography methods, allowing light to create impressions on metal plates.

One of the earliest uses of chemical etching to mill commercial parts was in 1927, when the Swedish company Aktiebolaget Separator patented a method of producing edge filters by chemically milling the gaps in the filters.[8] Later, around the 1940s, it became widely used to machine thin samples of very hard metal; photo-etching from both sides was used to cut sheet metal, foil, and shim stock to create shims, recording heat frets, and other components.[9]

Applications

Chemical milling has applications in the printed circuit board and semiconductor fabrication industries. It is also used in the aerospace industry[10] to remove shallow layers of material from large aircraft components, missile skin panels, and extruded parts for airframes. Etching is used widely to manufacture integrated circuits and Microelectromechanical systems.[10] In addition to the standard, liquid-based techniques, the semiconductor industry commonly uses plasma etching.

Process

Chemical milling is normally performed in a series of five steps: cleaning, masking, scribing, etching, and demasking.[2]

Cleaning

Cleaning is the preparatory process of ensuring that the surface to be etched is free of contaminants which could negatively impact the quality of the finished part.[2][11] An improperly cleaned surface could result in poor adhesion of the maskant, causing areas to be etched erroneously, or a non-uniform etch rate which could result in inaccurate final dimensions. The surface must be kept free from oils, grease, primer coatings, markings and other residue from the marking out process, scale (oxidation), and any other foreign contaminants. For most metals, this step can be performed by applying a solvent substance to the surface to be etched, washing away foreign contaminants. The material may also be immersed in alkaline cleaners or specialized de-oxidizing solutions. It is common practice in modern industrial chemical etching facilities that the workpiece never be directly handled after this process, as oils from human skin could easily contaminate the surface.[3]

Masking

Masking is the process of applying the maskant material to the surface to ensure that only desired areas are etched.[2][3] Liquid maskants may be applied via dip-masking, in which the part is dipped into an open tank of maskant and then the maskant dried. Maskant may also be applied by flow coating: liquid maskant is flowed over the surface of the part. Certain conductive maskants may also be applied by electrostatic deposition, where electrical charges are applied to particles of maskant as it is sprayed onto the surface of the material. The charge causes the particles of maskant to adhere to the surface.[12]

Maskant types

The maskant to be used is determined primarily by the chemical used to etch the material, and the material itself. The maskant must adhere to the surface of the material, and it must also be chemically inert enough with regards to the etchant to protect the workpiece.[3] Most modern chemical milling processes use maskants with an adhesion around 350 g cm-1; if the adhesion is too strong, the scribing process may be too difficult to perform. If the adhesion is too low, the etching area may be imprecisely defined. Most industrial chemical milling facilities use maskants based upon neoprene elastomers or isobutylene-isoprene copolymers. [13]

Maskants to be used in photochemical machining processes must also possess the necessary light-reactive properties.

Scribing

Scribing is the removal of maskant on the areas to be etched.[2] For decorative applications, this is often done by hand through the use of a scribing knife, etching needle or similar tool; modern industrial applications may involve an operator scribing with the aid of a template or use computer numerical control to automate the process. For parts involving multiple stages of etching, complex templates using colour codes and similar devices may be used.[14]

Etching

Etching is the actual immersion of the part into the chemical bath, and the action of the chemical on the part to be milled.[15] The time spent immersed in the chemical bath determines the depth of the resulting etch; this time is calculated via the formula:

Where E is the rate of etching (usually abbreviated to etch rate), s is the depth of the cut required, and t is the total immersion time.[10] [15] Etch rate varies based on a number of factors, including the concentration and composition of the etchant, the material to be etched, and temperature conditions. Due to its inconstant nature, etch rate is often determined experimentally immediately prior to the etching process. A small sample of the material to be cut, of the same material specification, heat-treatment condition, and approximately the same thickness is etched for a certain time; after this time, the depth of the etch is measured and used with the time to calculate the etch rate.[16] Aluminium is commonly etched at rates around 0.178 cm/hr, and magnesium about 0.46 cm/hr.[10]

Demasking

Demasking is the combined process of clearing the part of etchant and maskant.[2][17] Etchant is generally removed with a wash of clear, cold water (although other substances may be used in specialized processes). A de-oxidizing bath may also be required in the common case that the etching process left a film of oxide on the surface of the material. Various methods may be used to remove the maskant, the most common being simple hand removal using scraping tools. This is frequently both time-consuming and laborious, so for large-scale processes this step may be automated.[18]

Common etchants

- For aluminium

- For steels

- hydrochloric and nitric acids

- ferric chloride for stainless steels

- Nital (a mixture of nitric acid and ethanol, methanol, or methylated spirits for mild steels.

2% Nital is common etchant for plain carbon steels.

- For copper

- cupric chloride

- ferric chloride

- ammonium persulfate

- ammonia

- 25-50% nitric acid.

- hydrochloric acid and hydrogen peroxide

- For silica

- hydrofluoric acid (HF) is a very efficient etchant for silicon dioxide. It is however very dangerous if it comes into contact with the body.

Notes

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. xiii.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Çakir, O.; Yardimeden, A.; Özben, T. (August 2007). "Chemical machining". Archives of Materials Science and Engineering 28 (8): 499–502. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Harris 1976, p. 32.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Harris 1976, p. 2.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 6.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 9.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 10.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 15.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 17.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Fishlock, David (8 December 1960). "New Ways of Cutting Metal". New Scientist 8 (212): 1535. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 31.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 36.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 33.

- ↑ Harris 1976, pp. 37-44.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Harris 1976, p. 44.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 45.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 54.

- ↑ Harris 1976, p. 56.

References

- Harris, William T. (1976). Chemical Milling: The Technology of Cutting Materials by Etching. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0 19 859115 2.

External links

See also

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||