Cheletropic reaction

Cheletropic reactions are a type of pericyclic reaction. A pericyclic reaction is one that involves a transition state with a cyclic array of atoms and an associated cyclic array of interacting orbitals. A reorganization of σ and π bonds occurs in this cyclic array.[1]

Specifically, cheletropic reactions are a subclass of cycloadditions. The only difference is that on one of the reagents, both new bonds are being made to the same atom.[2] A few examples are shown to the right. In the first case, the single atom is the carbonyl carbon that ends up in carbon monoxide. The end result is making two new bonds to one atom. The first two examples are known as cheletropic extrusions because a small stable molecule is given off in the reaction. The driving force for these reactions is often the entropic benefit of gaseous evolution (e.g. CO or N2).[1]

Theoretical Analysis

In the pericyclic transition state, a small molecule donates two electrons to the ring.The reaction process can be shown using two different geometries. The small molecule can approach in a linear or non-linear fashion. In the linear approach, the electrons in the orbital of the small molecule are pointed directly at the π system. In the non-linear approach, the orbital approaches at a skew angle. The π-systems ability to rotate as the small molecule approaches is crucial in forming new bonds. The direction of rotation will be different depending on how many π-electrons are in the system. Shown below is a diagram of a two-electron fragment approaching a four-electron π-system using frontier molecular orbitals. The rotation will be disrotatory if the small molecule approaches linearly and conrotatory if the molecule approaches non-linearly. Disrotatory and conrotatory are sophisticated terms expressing how the bonds in the π-system are rotating. Disrotatory means opposite directions while conrotatory means the same direction. This is also depicted in the diagram below.

Using Huckel's Rule, one can tell if the π-system is aromatic or anti-aromatic. If aromatic, linear approaches use disrotatory motion while non-linear approaches use conrotatory motion. The opposite goes with an anti-aromatic system. Linear approaches will have conrotatory motion while non-linear approaches will have disrotatory motion.[1]

Cheletropic Reactions Involving SO2

Thermodynamics

In 1995, Suarez and Sordo showed that sulfur dioxide when reacted with butadiene and isoprene gives two different products depending on the mechanism. This was shown experimentally and using Gaussian calculations. A kinetic and thermodynamic product are both possible, but the thermodynamic product is more favorable. The kinetic product arises from a Diels-Alder reaction, while a cheletropic reaction gives rise to a more thermodynamically stable product. The cheletropic pathway is favored because it gives rise to a more stable five-membered ring adduct. The scheme below shows the difference between the two products. The path to the right shows the more stable thermodynamic product, while the path to the left shows the kinetic product.[3]

Kinetics

The cheletropic reactions of 1,3-dienes with sulfur dioxide have been extensively investigated in terms of kinetics (see above for general reaction).

In the first quantitative measurement of kinetic parameters for this reaction, a 1976 study by Isaacs and Laila measured the rates of addition of sulfur dioxide to butadiene derivatives. Rates of addition were monitored in benzene at 30 °C with an initial twentyfold excess of sulfur dioxide, allowing for a pseudo first-order approximation. The disappearance of SO2 was followed spectrophotometrically at 320 nm. The reaction showed pseudo first-order kinetics. Some interesting results were that electron-withdrawing groups on the diene decreased the rate of reaction. Also, the reaction rate was affected considerably by steric effects of 2-substituents, with more bulky groups increasing the rate of reaction. The authors attribute this to the tendency of bulky groups to favor the cisoid conformation of the diene which is essential to the reaction (see table below). In addition, the rates at four temperatures were measured for seven of the dienes permitting calculations of the enthalpy of activation (ΔH‡) and entropy of activation (ΔS‡) for these reactions through the Arrhenius equation.[4]

| -Butadiene | 104 k /min−1 (30 °C) (± 1-2%) absolute | 104 k /min−1 (30 °C) (± 1-2%) relative | ΔH‡ /kcal mol−1 | ΔS‡ /cal mol−1 K−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-methyl | 1.83 | 1.00 | 14.9 | -15 |

| 2-ethyl | 4.76 | 2.60 | 10.6 | -20 |

| 2-isopropyl | 13.0 | 7.38 | 12.5 | -17 |

| 2-tert-butyl | 38.2 | 20.8 | 10.0 | -19 |

| 2-neopentyl | 17.2 | 9.4 | 11.6 | -18 |

| 2-cloro | 0.24 | 0.13 | N/A | N/A |

| 2-bromoethyl | 0.72 | 0.39 | N/A | N/A |

| 2-p-tolyl | 24.7 | 13.5 | 10.4 | -19 |

| 2-phenyl | 17.3 | 9.45 | N/A | N/A |

| 2-(p-bromophenyl) | 9.07 | 4.96 | N/A | N/A |

| 2,3-dimethyl | 3.54 | 1.93 | 12.3 | -18 |

| cis-1-methyl | 0.18 | 0.10 | N/A | N/A |

| trans-1-methyl | 0.69 | 0.38 | N/A | N/A |

| 1,2-dimethylene-cyclohexane | 24.7 | 13.5 | 11.4 | -16 |

| 2-methyl-1,1,4,4-d4 | 1.96 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

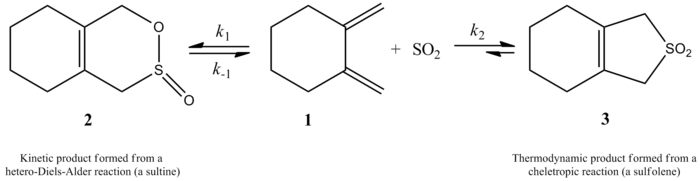

More recently, a 2002 study by Monnat, Vogel, and Sordo measured the kinetics of addition of sulfur dioxide to 1,2-dimethylidenecycloalkanes. An interesting point presented in this paper is that the reaction of 1,2-dimethylidenecyclohexane with sulfur dioxide can give two different products depending on reaction conditions. The reaction produces the corresponding sultine through a hetero-Diels-Alder reaction under kinetic control (≤ -60 °C), but, under thermodynamic control (≥ -40 °C), the reaction produces the corresponding sulfolene through a cheletropic reaction. The activation enthalpy for the hetero-Diels-Alder reaction is about 2 kcal/mol smaller than that for the corresponding cheletropic reaction. The sulfolene is about 10 kcal/mol more stable than the isometric sultine in CH2Cl2/SO2 solution.[5]

The authors were able to experimentally determine a rate law at 261.2 K for the reaction of 1,2-dimethylidenecyclohexane with sulfur dioxide to give the corresponding sulfolene. The reaction was first order in 1,2-dimethylidenecyclohexane but second order in sulfur dioxide (see below). This confirmed a prediction based on high-level ab initio quantum calculations. Using computational methods, the authors proposed a transition structure for the cheletropic reaction of 1,2-dimethylidenecyclohexane with sulfur dioxide (see figure at right).[5] The reaction is second order in sulfur dioxide because another molecule of sulfur dioxide likely binds to the transition state to help stabilize it.[6] Similar results were found in an 1995 study by Suarez, Sordo, and Sordo which used ab initio calculations to study the kinetic and thermodynamic control of the reaction of sulfur dioxide with 1,3-dienes.[3]

Solvent effects

The effect of the solvent of the cheletropic reaction of 3,4-dimethyl-2,5-dihydrothiophen-1,1-dioxide (shown at right) was kinetically investigated in 14 solvents. The reaction rate constants of the forward and reverse reaction in addition to the equilibrium constants were found to be linearly correlated with the ET(30) solvent polarity scale.

Reactions were done at 120 °C and were studied by 1H-NMR spectroscopy of the reaction mixture. The forward rate k1 was found to decrease by a factor of 4.5 going from cyclohexane to methanol. The reverse rate k-1 was found to increase by a factor of 53 going from cyclohexane to methanol, while the equilibrium constant Keq decreased by a factor of 140. It is suggested that there is a change of the polarity during the activation process as evidenced by correlations between the equilibrium and kinetic data. The authors remark that the reaction appears to be influenced by the polarity of the solvent, and this can be explained by the change in the dipole moments when going from reactant to transition state to product. The authors also state that the cheletropic reaction doesn’t seem to be influenced by either solvent acidity or basicity.

The results of this study lead the authors to expect the following behaviors:

1. The change in the solvent polarity will influence the rate less than the equilibrium.

2. The rate constants will be characterized by opposite effect on the polarity: k1 will slightly decrease with the increase of ET(30), and k-1 will increase under the same conditions.

3. The effect on k-1 will be larger than on k1.[7]

Carbene Additions to Alkenes

One of the most synthetically important cheletropic reactions is the addition of a singlet carbene to an alkene to make a cyclopropane (see figure at left).[1] A carbene is a neutral molecule containing a divalent carbon with six electrons in its valence shell. Due to this, carbenes are highly reactive electrophiles and generated as reaction intermediates.[8] A singlet carbene contains an empty p orbital and a roughly sp2 hybrid orbital that has two electrons. Singlet carbenes add stereospecifically to alkenes, and alkene stereochemistry is retained in the cyclopropane product.[1] The mechanism for addition of a carbene to an alkene is a concerted [2+1] cycloaddition (see figure). Carbenes derived from chloroform or bromoform can be used to add CX2 to an alkene to give a dihalocyclopropane, while the Simmons-Smith reagent adds CH2.[9]

Interaction of the filled carbene orbital with the alkene π system creates a four-electron system and favors a non-linear approach. It is also favorable to mix the carbene empty p orbital with the filled alkene π orbital. Favorable mixing occurs through a non-linear approach (see figure at right). However, while theory clearly favors a non-linear approach, there are no obvious experimental implications for a linear vs. non-linear approach.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Eric V. Anslyn and Dennis A. Dougherty Modern Physical Organic Chemistry University Science Books, 2006.

- ↑ Ian Fleming. Frontier Orbitals and Organic Chemistry Reactions. Wiley, 1976.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Suarez, D.; Sordo, T. L.; Sordo, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 2848-2852, doi 10.1021/jo00114a039.

- ↑ Isaacs, N. S.; Laila, A. A. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 715-716, doi 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)74605-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Monnat, F.; Vogel, P.; Sordo, J. A. Helv. Chim. Acta 2002, 85, 712-732, doi 10.1002/1522-2675(200203)85:3<712::AID-HLCA712>3.0.CO;2-5.

- ↑ Fernandez, T.; Sordo, J. A.; Monnat, F.; Deguin, B.; Vogel, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 13276-13277, doi 10.1021/ja982565p.

- ↑ Desimoni, G.; Faita, G.; Garau, S.; Righetti, P. (1996). Tetrahedron 52 (17): 6241–6248. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00279-7.

- ↑ John McMurry Organic Chemistry, 6th Ed. Thomson, 2004.

- ↑ Robert B. Grossman The Art of Writing Reasonable Organic Reaction Mechanisms Springer, 2003.

![{\frac {d[3]}{dt}}=k_{2}[1][SO_{2}]^{2}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/9/3/c/7/93c7cb8a292a68ee0486519eb244b3e5.png)