Charles Otis Whitman

| Charles Otis Whitman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

December 6, 1842 Woodstock, Maine, USA |

| Died |

December 14, 1910 (aged 68) Worcester, Massachusetts, USA |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Fields | Zoology |

Charles Otis Whitman (December 14, 1842 – December 6, 1910) was an American zoologist, who introduced modern zoological studies to Japan, and was influential to the founding of classical ethology.[1] A dedicated educator who preferred to teach a few research students at a time, he made major contributions in the areas of evolution and embryology of worms, comparative anatomy, heredity, and animal behaviour.

Biography

Whitman was born in Woodstock, Maine. His parents were Adventist pacifists and prevented his efforts to enlist in the Union army in 1862. He worked as a part-time teacher, and converted to Unitarianism. He graduated from Bowdoin College in 1868. Following graduation Whitman became principal of the Westford Academy, a small Unitarian-oriented college preparatory school outside Lowell, Massachusetts. In 1872 he moved to Boston and after becoming a member of the Boston Society of Natural History in 1874, he decided to study zoology full-time. In 1875 he took a leave of absence and went to the University of Leipzig in Germany to complete a Ph.D. which he obtained in 1878.

A year later he received a postdoctoral fellowship at the Johns Hopkins University, but immediately gave it up when after recommended by noted biologist Edward Sylvester Morse, he was hired by the Japanese government to succeed Morse as professor at the Tokyo Imperial University from 1879-1881. Influenced by his training in Germany, he introduced systematic methods of biological research, including the use of the microscope.

After leaving Japan, Whitman performed research at the Naples Zoological Station (1882), became an assistant at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University (1883–5), then directed the Allis Lake Laboratory, in Milwaukee (1886–9), where he founded the Journal of Morphology (1887).

In 1884, Whitman married Emily Nunn. He moved to Clark University (Worcester, Massachusetts) (1889–92), then became a professor and curator of the Zoological Museum at the University of Chicago (1892–1910),[2] while concurrently serving as founding director of the Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts (1888–1908).[3] During the 1880s, Whitman established himself as the central figure of academic biology in the United States. He systematized the procedures that European anatomists and zoologists had gradually developed ever the past two decades.

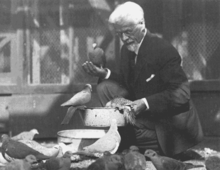

Over the course of his career, Whitman worked with more than 700 species of pigeons, studying the relationship between phenotypic variation and heredity. By the turn of the 20th century, the last group of Passenger Pigeons, all descended from the same pair, was kept by Whitman at the University of Chicago.[4] The last attempt to breed the remaining specimens was done by Whitman and the Cincinnati Zoo, which included attempts at making a rock dove foster Passenger Pigeon eggs.[5] Whitman sent Martha, which was to be the last known specimen, to Cincinnati Zoo in 1902.[6]

In December 1910, however, he caught a chill, and died a few days later.

Whitman was a non-Darwinian evolutionist. Stephen Jay Gould wrote that Whitman did not believe in Lamarckism, Darwinism or mutationism, instead Whitman was an advocate of orthogenesis. Whitman only wrote one book on orthogenesis which was published nine years after his death in 1919 titled Orthogenetic evolution in pigeons the book was published in a three volume set titled Posthumous Works of Charles Otis Whitman,[7][8] Gould claims that the book was written "too late, to win any potential influence".[9]

Partial bibliography

- A contribution to the embryology, life-history, and classification of the Dicyemids (1882)

- The Leeches of Japan (1886)

- The Naturalist's Occupation (1891)

- Evolution and epigenesis: Bonnet's theory of evolution, a system of negations (1895)

- Animal Behavior (1899)

- The metamerism of clepsine (1912)

- Posthumous Works of Charles Otis Whitman (1919)

Notes

- ↑ Danchin. Behavioural Ecology. pp.16

- ↑ Dugatkin. The Altruism Equation. pp.38

- ↑ Sapp. Genesis:The Evolution of Biology. pp.84

- ↑ Rothschild, Walter (1907). Extinct Birds. London: Hutchinson & Co.

- ↑ d'Elia, J. (2010). "Evolution of Avian Conservation Breeding with Insights for Addressing the Current Extinction Crisis". Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 1 (2): 189–210. doi:10.3996/062010-JFWM-017.

- ↑ Burkhardt, R. W. (2005) Patterns of behavior: Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen, and the founding of ethology, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226080900

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/2456225

- ↑ http://embryo.asu.edu/view/embryo:125550

- ↑ The structure of evolutionary theory, Stephen Jay Gould, 2002, p. 283

References

- Danchin, Etienne (2008). Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Perspective on Behaviour. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920629-5.

- Sapp, Jan (2003). Genesis:The Evolution of Biology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515619-6.

- Dugatkin, Lee Allan (2003). The Altruism Equation: Seven Scientists Search for the Origins of Goodness. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12590-2.

- Morse, Edward Sylvester (1912). Biographical memoir of Charles Otis Whitman, 1842-1910. National Academy of Sciences. ASIN: B00087SMU0.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Charles Otis Whitman |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: |

|