Chandralekha (1948 film)

| Chandralekha | |

|---|---|

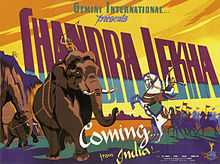

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | S. S. Vasan |

| Produced by | S. S. Vasan |

| Written by |

Veppathur Kittoo Kothamangalam Subbu K. J. Mahadevan Sangu Naina |

| Based on |

Robert McCaire the Male Bandit by G. W. M. Reynolds |

| Starring |

M. K. Radha Ranjan T. R. Rajakumari |

| Music by |

Songs: S. Rajeswara Rao Background music: M. D. Parthasarathy |

| Cinematography |

Kamal Ghosh K. Ramnoth |

| Editing by | Chandru |

| Distributed by | Gemini Studios |

| Release dates | 9 April 1948 |

| Running time | 210 minutes[1] |

| Country | India |

| Language |

Tamil Hindi |

| Budget |

|

| Box office |

|

Chandralekha (also spelled Chandraleka[lower-alpha 1]) is a 1948 Indian historical fiction film directed and produced by S. S. Vasan for Gemini Studios. The film features T. R. Rajakumari in the title role and M. K. Radha as the male lead, with Ranjan as the primary antagonist. The film's music was composed by S. Rajeswara Rao and M. D. Parthasarathy, with a script by Gemini's story department: Veppathur Kittoo, Kothamangalam Subbu,[lower-alpha 2] K. J. Mahadevan, Sangu and Naina.[1] A "Ruritanian period extravaganza",[2] the film tells the story of two royal brothers and rivals, Veerasimhan and Sasankan, and a country maiden and dancer, Chandralekha.

Development for Chandralekha began in 1943 when Vasan, after two successive hit films, announced that his next film would be entitled Chandralekha. However, when he launched an advertising campaign for the film, all he had was the name of the heroine from a storyline he had rejected about a tough woman. One of his storyboard artists, Veppathur Kittoo, then developed a story based on the novel Robert McCaire the Male Bandit, that impressed Vasan. The original director of Chandralekha was T. G. Raghavachari, who (after directing more than half the film) left the project due to disagreements with Vasan, who took over the film in his directorial debut.

Originally filmed in Tamil and later in Hindi, Chandralekha was in production for five years from 1943 to 1948. There were a number of changes to the script, cast and production, and the film ultimately cost over ![]() 3 million. It was the most expensive film made in India at the time; the cost of filming a single sequence equalled the entire budget of a typical Indian film of the time. After massive publicity, Chandralekha was released on 9 April 1948 and became a huge success, but it was not profitable due to its expense. Hence Vasan released the film in Hindi as well, and Chandralekha (both versions together) became India's first nationwide hit.

3 million. It was the most expensive film made in India at the time; the cost of filming a single sequence equalled the entire budget of a typical Indian film of the time. After massive publicity, Chandralekha was released on 9 April 1948 and became a huge success, but it was not profitable due to its expense. Hence Vasan released the film in Hindi as well, and Chandralekha (both versions together) became India's first nationwide hit.

Plot

Veerasimhan (M. K. Radha) and Sasankan (Ranjan) are sons of the king of an unspecified region. When returning to his palace, Veerasimhan meets a village dancer named Chandralekha (T. R. Rajakumari) and they fall in love. Back at the palace, the king decides to abdicate in favour of Veerasimhan. This enrages the younger brother Sasankan, who leaves the palace and forms a gang of thieves who embark on a crime spree. They kill Chandralekha's father; orphaned, she joins a band of travelling musicians, but their caravan is raided by Sasankan's men.

Sasankan orders Chandralekha to dance for him, and she does so only after being whipped, but eventually manages to escape. Meanwhile, Sasankan mounts a surprise attack on Veerasimhan and takes him prisoner. Chandralekha witnesses Sasankan's men trapping Veerasimhan in a cave, and with the help of a circus troupe passing by, rescues him. The two fugitives now join the circus to hide from Sasankan's men. Meanwhile, Sasankan returns to the kingdom, imprisons his parents and declares himself king. Remembering Chandralekha, he asks his men to find her.

At the circus, one of Sasankan's men sees Chandralekha performing and tries to capture her, but she is saved by Veerasimhan. Both of them escape and join a gypsy group, but when Veerasimhan goes looking for assistance, Sasankan's men capture Chandralekha and bring her to the palace. Sasankan orders her to marry him; she refuses, feigning unconsciousness when he approaches her. Finally, one of her friends from the circus comes to Sasankan disguised as a gypsy healer, and claims she can heal Chandralekha. Behind locked doors, a quick conference takes place between the two girls. Sasankan is pleased to find Chandralekha miraculously cured and even ready to accept him as a bridegroom. In return, he agrees to her request for a drum dance to celebrate the royal wedding.

Huge drums are arranged in rows in front of the palace. Chandralekha joins the dancers and Sasankan is impressed with her performance. As the dance ends, the drums open and from within them swarms of soldiers appear and attack Sasankan's men. Veerasimhan and his men manage to storm into the castle. He confronts Sasankan and both engage in a long sword fight, which ends with Sasankan's defeat and imprisonment. Veerasimhan releases his parents and takes over as the new king, while Chandralekha becomes his queen.

Cast

- Main cast

- T. R. Rajakumari as Chandralekha, a village dancer and circus artiste

- M. K. Radha as Veerasimhan, the older of two princes and Chandralekha's love interest

- Ranjan as Sasankan, Veerasimhan's younger brother

- Supporting cast

- M. S. Sundari Bai as a dancer in "Naatiya Kudhirai"

- N. S. Krishnan and T. A. Mathuram as circus performers

Other supporting actors were L. Narayana Rao, V. N. Janaki, T. E. Krishnamachariar, Subbiah Pillai, Pottai Krishnamoorthy, N. Seetharaman, N. Ramamurthi, Veppathur Kittoo, Velayutham, Ramakrishna Rao, Cocanada Rajarathnam, Seshagiri Bhagavathar, T. V. Kalyani, Varalakshmi, V. S. Susheela, Appanna Iyengar, Sundara Rao, Surabhi Kamala and "100 Gemini Boys and 500 Gemini Girls".[3] Additionally, S. N. Lakshmi appears in an uncredited role as a dancer in the drum dance sequence.[4]

Production

Development

In 1943,[5] S. S. Vasan was contemplating a story for his third film after Mangamma Sabatham (1943) and the Telugu film Balanagamma (1942), which netted a profit of ![]() 4 million. Vasan wanted a film on a grand scale, and there were no budgetary constraints. He asked Gemini Studio's story department to write a screenplay; writers such as Kothamangalam Subbu and Veppathur Kittoo said that Mangamma Sabatham and Balanagamma had heroine-oriented plots, and proposed a similar story to Vasan. They told a story about Chandralekha, a tough woman who fights a bandit and cuts off his nose. Vasan disliked its gruesomeness and vulgarity, and rejected the story. However, the character's name, Chandralekha, stayed in his mind.

4 million. Vasan wanted a film on a grand scale, and there were no budgetary constraints. He asked Gemini Studio's story department to write a screenplay; writers such as Kothamangalam Subbu and Veppathur Kittoo said that Mangamma Sabatham and Balanagamma had heroine-oriented plots, and proposed a similar story to Vasan. They told a story about Chandralekha, a tough woman who fights a bandit and cuts off his nose. Vasan disliked its gruesomeness and vulgarity, and rejected the story. However, the character's name, Chandralekha, stayed in his mind.

Without waiting for the full story, Vasan announced that his next project would be Chandralekha, publicising it with full-page advertisements. Despite work by Gemini's writers, even after three months the story was not ready. Vasan became impatient, and considered shelving Chandralekha in favour of Avvaiyyar (his other project). Kittoo received a week's extension and discovered an English novel by G. W. M Reynolds entitled Robert McCaire The Male Bandit, in which he read:

... it's night in rural England and a mail coach convoy trots its way, when, suddenly, Robert McCaire, the bandit, and his henchmen on horses emerge from the surrounding darkness, hold up the convoy and rob it. Hiding under a seat is a young woman fleeing from a harsh home. She is a dancer and when she refuses to dance, the bandit whips her into submission ...

Vasan was impressed with Kittoo's story, based on this episode; deciding to continue with the film, he named the heroine Chandralekha, although the rest of the story was still incomplete.[6] The rest of Gemini's story department later improvised Kitto's story to give it a final shape.[7]

Casting

The script had two major roles, princes of a kingdom; the elder was the protagonist and his brother a villainous, amoral person. M. K. Radha was originally chosen for the younger prince, Sasankan, but declined the negative role and agreed to play the older prince Veerasimhan.[7] It was Radha's wife who convinced Vasan to cast Radha as the older prince. K. J. Mahadevan was chosen by Vasan to play the younger prince, and T. G. Raghavachari agreed to direct the film;[6] however, after the first few scenes featuring Mahadevan were shot, his performance was deemed "too soft", and he was dismissed from the role.[5] However, he still served as one of the film's scriptwriters[1] and was also an assistant director.[8]

Raghavachari wanted Ranjan to play Sasankan. Vasan was opposed, feeling Ranjan was too effeminate to play a "steel-hard villain", but reluctantly agreed. Ranjan, for his part, was surprised that Vasan was considering him for a villainous role. Despite his commitment to B. N. Rao's Saalivaahanan (1945), Kittoo persuaded Ranjan to take a screen test for Chandralekha and Rao gave him a few days off. The test was successful, and Ranjan got the part.[9] T. R. Rajakumari was chosen to play Chandralekha,[6] replacing K. L. V. Vasantha, who was Vasan's first choice.[10]

In April 1947 comedian N. S. Krishnan was released from prison,[lower-alpha 3] and Vasan recruited him and T. A. Mathuram to act in Chandralekha as circus performers who help the hero to rescue the titular character from the antagonist.[6] The script was altered, with scenes added to showcase the comedy team.[11] S. N. Lakshmi made her film debut as a dancer in the climactic drum-dancing scene.[4][12] M. S. Sundari Bai appeared as a dancer in "Naatiya Kudhirai",[13] and T. A. Jayalakshmi appeared briefly in only one scene that lasted for a few minutes.[14]

A minor role, the hero's bodyguard, was not yet cast. Struggling stage actor Villupuram Chinniah Pillai Ganeshamurthy (the future Sivaji Ganesan) was interested in the role, growing his hair long for the part. He contacted Veppathur Kittoo several times asking for a role in the film. Eventually, Kittoo took Ganesan to Vasan, who had seen him perform on stage. However, Vasan rejected Ganesan, telling him to choose another profession. This incident is cited as having possibly caused a permanent rift between Vasan and Ganesan.[6]

Filming

During the film's making our studio looked like a small kingdom ... horses, elephants, lions, tigers in one corner, palaces here and there, over there a German lady training nearly a hundred dancers on one studio floor, a shapely Sinhalese lady teaching another group of dancers on real marble steps adjoining a palace, a studio worker making weapons, another making period furniture using expensive rosewood, others set props, headgear, and costumes, Ranjan undergoing fencing practice with our fight composer 'Stunt' Somu, our music directors composing and rehearsing songs in a building ... there were so many activities going on simultaneously round-the-clock in the same place.

Chandralekha began shooting in 1943,[5] and Raghavachari directed more than half the film. Due to differences of opinion between him and Vasan over shooting scenes at the Governor's Estate, Raghavachari left the project and Vasan made his directorial debut.[6]

The film initially had no circus scenes. Vasan decided to include them when the film was halfway through production, and the screenplay was changed.[11] Kittoo travelled throughout South India and Ceylon to see over 50 circuses[6] before choosing the Kamala Circus Company and Parasuram Lion Circus.[15] The circus scenes were shot by K. Ramnoth; staff members, their families and passersby were recruited as spectators in the scenes.[11] The circus scenes lasted for 20 minutes, according to G. Dhananjayan "the longest footage of scenes outside the main plot that one can see".[7] A scene in which Ranjan whips Rajakumari when she refuses to dance was based on the passage from Robert McCaire the Male Bandit, from which Kittoo developed the storyline that Vasan was impressed with.[11]

After Raghavachari's departure, one sequence he directed remained in the film: the drum-dance scene.[16][17] This scene (the first of its kind in Indian cinema) involved 400 dancers and six months of rehearsals; it was designed by chief art director A. K. Sekhar,[6] choreographed by Jayashankar[11] and shot with four cameras by Ellapa, C. V. Ramakrishnan, S. Maruthi Rao[7] and (primarily) Kamal Ghosh.[18] The drum dance alone cost ![]() 5,00,000 ($105 000.11 in 1948 dollars),[lower-alpha 4] equal to the complete budget for a typical Indian film of the time. Elements and footage from the 1937 Hollywood film The Prisoner of Zenda were freely used in the film.[7]

5,00,000 ($105 000.11 in 1948 dollars),[lower-alpha 4] equal to the complete budget for a typical Indian film of the time. Elements and footage from the 1937 Hollywood film The Prisoner of Zenda were freely used in the film.[7]

During post-production, Ramnoth was asked his opinion by Vasan of the scene in which hundreds of Veerasimhan's warriors storm the palace to rescue Chandralekha from Sasankan. Although everyone else praised the scene's photography, shots and action, Ramnoth remained quiet, finally saying that the suspense could be ruined if the scene was shown uncut. This sparked a discussion; Vasan advised editor Chandru to edit according to Ramnoth, and was impressed with the result.[19]

Chandralekha was under production for five years (from 1943 to 1948) and underwent a number of changes to its story, cast and filming. This caused substantial time and cost overruns; the film cost ![]() 3 million (about $600,000 in 1948 dollars),[lower-alpha 4] the most expensive Indian film till then.[6] Adjusted for inflation, it would have cost US$28 million in 2010.[20]

3 million (about $600,000 in 1948 dollars),[lower-alpha 4] the most expensive Indian film till then.[6] Adjusted for inflation, it would have cost US$28 million in 2010.[20]

Music

The film's soundtrack was composed by S. Rajeswara Rao,[21] with lyrics by Papanasam Sivan and Kothamangalam Subbu.[22] R. Vaidyanathan and B. Das Gupta collaborated with M. D. Parthasarathy on the background music.[21] According to film critics V. A. K. Ranga Rao[23] and Shoma A Chatterji, the music is influenced by Carnatic and Hindustani music, Latin and Portuguese folk music and Strauss waltzes.[24] The song "Naattiya Kuthirai" was not originally in the script, and was added during the final stages of the film's production (possibly inspired by the 1943 musical, Coney Island).[13] "Indrae Enathu Kuthukalam" and "Manamohana Saaranae" were sung by Rajakumari.[7] The circus chorus was adapted from "The Donkey Serenade" from R. Z. Leonard's The Firefly (1937).[23][25] After Chandralekha, musical directors in Tamil cinema were more influenced by Western music.[26]

- Tamil tracklisting[27]

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Indrae Enathu Kuthukalam" | T. R. Rajakumari | 1:09 | |

| 2. | "Aathoram Kodikkalam" | M. D. Parthasarathy[28] | 2:23 | |

| 3. | "Padathey Padathey Nee" | M. S. Sundari Bai | 3:29 | |

| 4. | "Naattiya Kuthirai" | M. D. Parthasarathy[28] | 4:09 | |

| 5. | "Namasthey Sutho" | Chorus | 4:10 | |

| 6. | "Group Dance" (Instrumental) | — | 1:25 | |

| 7. | "Aayilo Pakiriyamo" | N. S. Krishnan, T. A. Mathuram | 3:10 | |

| 8. | "Manamohana Saaranae" | T. R. Rajakumari | 2:30 | |

| 9. | "Murasu Aatam (Drum Dance)" (Instrumental) | — | 5:59 |

- Hindi tracklisting[29]

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sajana Re Aaja Re" | Uma Devi | 3:04 | |

| 2. | "Man Bhavan Sawan Aaya" | Uma Devi | 3:09 | |

| 3. | "O Chand Mere" | Uma Devi | 3:21 | |

| 4. | "Maai Re Main To Madhuban Mein" | Uma Devi | 2:33 | |

| 5. | "Sanjh Ki Bela" | Uma Devi, Moti Bai | 3:07 | |

| 6. | "Mera Husn Lootne Aaya Albela" | Zohra Ambala, Moti Bai | 2:41 |

Marketing

The first advertisement for Chandralekha appeared on the back cover of the songbook for the film Dasi Aparanji (1944). It featured Vasantha as the heroine (before she was replaced by Rajakumari).[11][lower-alpha 5]

With Chandralekha, Gemini became the first Tamil studio to try distributing a film all over India.[22] Vasan spent nearly ![]() 5,00,000 on publicity, one of the most expensive campaigns of the era. Chandralekha was released simultaneously in 40 theatres throughout South India, and in another 10 within a week.[7] An abridged English-language version of Chandralekha, Chandra, was shown in the United States and Europe during the 1950s.[5][30]

5,00,000 on publicity, one of the most expensive campaigns of the era. Chandralekha was released simultaneously in 40 theatres throughout South India, and in another 10 within a week.[7] An abridged English-language version of Chandralekha, Chandra, was shown in the United States and Europe during the 1950s.[5][30]

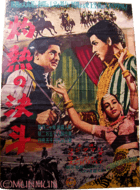

Chandralekha was released in Japan in April 1954, where it was distributed by Nippon Cinema Corporation (NCC). It was the first Tamil film released in Japan, and the second Indian film (after the Hindi film, Aan). The NCC later collapsed, and no information survives about how the film was brought to Japan. During the 1950s, when India was short of foreign currency, barter was a common means of exchange with overseas business partners and Japanese scholar Tamaki Matsuoka believes this to have been the case with Chandralekha. The pamphlet prepared by NCC for Chandralekha, whose Japanese title was Shakunetsu-no ketto (Fight Under the Red Heat), calls Vasan the "Cecil B. DeMille of the Indian film industry".[31] A Danish version of the film, Indiens hersker (India's ruler), was released on 26 April 1954.[32]

Release

Reception

Chandralekha was released on 9 April 1948.[33] The film was a bellwether for its filming, production cost and publicity before, during and after its release. Other producers delayed releasing their films until after Chandralekha's release to avoid its competition. The film's entertainment value ensured its commercial success.[34]

Despite the original Tamil version's popularity, Chandralekha was not profitable (due to its expense) and Vasan decided to remake it in Hindi. He re-shot scenes, added songs and replaced comedy scenes with Hindi artistes. The Hindi version was released with over 600 prints[lower-alpha 6] and set box-office records, opening the market to South Indian producers.[7] Vasan called the film "a pageant for our peasants",[35] meant for "the war-weary public that had been forced to watch insipid war propaganda pictures for years".[36] Chandralekha was selected by the government of India for exhibition at the Fourth International Film Festival in Prague in 1949.[37]

Although exact figures are not available on the film's box office earnings, film trade websites provide estimates of its success. Sharmishtha Gooptu, author of Bengali Cinema: An Other Nation said that Chandralekha grossed ![]() 10 million (about $2,100,000 in 1948 dollars)[lower-alpha 4] in India,[38] the first Madras production to become a hit all over India.[1] Box Office India gives the Hindi version's nett gross as

10 million (about $2,100,000 in 1948 dollars)[lower-alpha 4] in India,[38] the first Madras production to become a hit all over India.[1] Box Office India gives the Hindi version's nett gross as ![]() 7 million (about $1,500,000 in 1948 dollars),[lower-alpha 4] and states that it was the second-highest-grossing Bollywood film of 1948 (after Shaheed, which earned a nett gross of

7 million (about $1,500,000 in 1948 dollars),[lower-alpha 4] and states that it was the second-highest-grossing Bollywood film of 1948 (after Shaheed, which earned a nett gross of ![]() 7.5 million).[39] IBOS Network estimates the film's adjusted worldwide gross as

7.5 million).[39] IBOS Network estimates the film's adjusted worldwide gross as ![]() 476.62 crore (US$76 million), the 71st highest-grossing Indian film (adjusted for inflation).[40]

476.62 crore (US$76 million), the 71st highest-grossing Indian film (adjusted for inflation).[40]

Critical response

India

Chandralekha received generally positive reviews from critics in India. On 9 April 1948, The Hindu said "India has not witnessed a film of this magnitude in terms of making and settings so far".[34] On 10 April, The Indian Express said "Chandralekha is an entertaining film for everyone with elements like animals, rope dance, circus and comedy".[34] The same day, the Tamil newspaper Dinamani said "Chandralekha is not only a first rate Tamil film but also an international film".[lower-alpha 7] Film critic V. A. K. Ranga Rao described the film as "the most complete entertainer ever made".[6] In their 1988 book One Hundred Indian Feature Films: An Annotated Filmography, writers Anil Srivastava and Shampa Banerjee praised nearly every aspect of the film such as its grandeur, battle scenes, and the drum dance, which they called the "raison d'etre" of the film.[41]

In a 2010 review of Chandralekha, film historian Randor Guy praised Rajakumari's performance, calling it "her career-best" and saying that she "carried the movie on her shoulders". Guy praised Radha as his "usual impressive self", saying the film would be "Remembered for: the excellent onscreen narration, the magnificent sets and the immortal drum dance sequence".[11] In 2003, journalist S. Muthiah called it "an epic extravaganza worthy of Cecil B. de. Mille" that was "larger-than-life".[42] Behindwoods.com praised the film's "mind-boggling artwork and production values".[43] In his 2011 book The Best of Tamil Cinema: 1931 to 1976, G. Dhananjayan called the film "a delight to watch even after 50 years".[7]

Director Dhanapal Padmanabhan said in a 2013 interview with K. Jeshi of The Hindu, "Chandralekha had grandeur that was at par with Hollywood standards".[44] Entertainment website IndiaGlitz praised the film for its "opulent songs and sinister plots".[45] In their 2008 book Global Bollywood: Travels of Hindi Song and Dance, writers Sangita Gopal and Sujata Moorti said: "Chandralekha is a film that translates the aesthetic of Hollywood Orientalism for an indigenous mass audience", calling its drum-dance sequence "perhaps one of the most spectacular sequences in Indian cinema".[46] In July 2007, director J. Mahendran listed the film as the first in his list of "best ten" films and told S. R. Ashok Kumar of The Hindu, "I choose Chandralekha, a remarkable film because of its grandeur in all departments of filmmaking. There are no graphics or special effects."[47] Director K. Balachander listed it as the second in his list of "best ten" films and told Ashok Kumar, "I have seen it [Chandralekha] 12 times", while praising the film for its "grand sets".[47] In May 2010, Raja Sen of Rediff praised the film's "grandly mounted setpieces", its "memorable drum dance" and the "longest swordfight ever captured on film", calling Chandralekha "just the kind of film, in fact, that would be best appreciated now after digital restoration".[48]

The film also received unfavourable comments. Though Anil Srivastava and Shampa Banerjee praised nearly every aspect of the film, they called the story "unreal".[41] Dhananjayan called Chandralekha "not a great film in terms of script".[34] Film critic M. K. Raghavendra said, "Indian films are rarely constructed in a way that makes undistracted viewing essential to their enjoyment and Chandralekha is arranged as a series of distractions" and concluded, "Chandralekha apparently shows us that enjoyment and visual pleasure in the Indian context are not synonymous with edge-of-the-seat excitement but must permit absent-mindedness as a viewing condition".[49]

Overseas

Chandralekha was also well received by critics overseas. Reviewing the English version, The New York Times described Rajakumari as a "buxom beauty".[50] American film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum said in August 1981, "The prospect of a three-hour Indian film in Temil [sic] with no subtitles is a little off-putting, I would say—wouldn't you?". However, he had "surprisingly little trouble following the plot and action" of the film, concluding "this made-in-Madras costume drama makes for a pretty action-packed 186 minutes. All things considered, it belongs to the same childhood continuum as Lang's late India-based movies, The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb".[51] In June 2009, K. S. Sivakumaran of Daily News Sri Lanka called it "the first colossal Thamil [sic] film I saw".[52] Jonathan Crow of the New York Times praised the film's "dance scenes that would make Busby Berkeley weep and some extremely catchy musical numbers", and mentioned that Chandralekha "set the standard for the Bollywood spectacular".[53] In 2013, Malaysian author D. Devika Bai praised the film for its "grand settings, palace intrigues, circus acts, splendid dances and dazzling fencing", while mentioning, "at almost 68, I have not tired of watching the movie."[54] When Chandralekha was shown in New York in 1976, American film historian William K. Everson said:

Chandralekha was pure home-grown De Mille, based on both legend and fact, but letting neither stand in the way of showmanship. It's a colorful, naive and zestful film in which the overall ingenuousness quite disarms criticism of plot absurdity or such production shortcomings as the too-obvious studio "exteriors". The only local criticism, however, was of its "excessive sensuality", but don't be alarmed—or excited—since this complaint was based on the then VERY rigid moral standards, now quite forgotten ...

The action has gusto and size, the songs are a joy, and the music guilelessly pillages from cultures all over the world, ranging from unexpurgated Wagner and Spanish flamenco to traditional Indian, with a snatch of the Laurel & Hardy theme thrown in as the comedians appear. Possibly the film's greatest moment occurs at the very beginning when after arriving at the huge palace (a most elaborate set) with his troops, the Prince strides through the palace, upstairs, along corridors, ever followed by a smoothly tracking camera which records the sumptuous splendor of it all, until he reaches his inner sanctum — where he sits down on a very moth-eaten second-hand chair and tugs off his boots! It's almost an unwitting Lubitsch touch ... With its fights, chases, music, elephants and a circus, Chandralekha was a huge popular success, the first Indian movie to be equally successful in both Tamil and then in Hindi versions. Last but far from least, Busby Berkeley would surely have been delighted to see his influence extending to the climactic drum dance.[1]

Cite error: There are<ref>tags on this page, but the references will not show without a{{reflist}}template (see the help page).

Differences between versions

Despite similarities to its Tamil version, the Hindi version of Chandralekha differs in several respects. Pandit Indra and Agha Jani Kashmiri wrote the dialogue for the Hindi version only.[55] Indra was a lyricist for the Hindi version (with Bharat Vyas), and Subbu and Papanasam Sivan were lyricists for the Tamil version.[56] Although Rajeswara Rao composed the soundtrack for both versions, he was assisted by Bal Krishna Kalla in the Hindi version. Parthasarathy and Vaidyanathan composed background music for the Hindi version, without Das Gupta.[57]

Differences between the casts also exist. Rajakumari, Radha and Ranjan reprised their roles in the Hindi version, but their characters were renamed (except for Rajakumari's character, Chandralekha). Radha's character Veerasimhan was known as Veer Singh in the Hindi version, and Ranjan's character Sasankan was renamed Shashank.[58] Of the other cast members, N. S. Krishnan, T. A. Mathuram, T. E. Krishnamachariar, Pottai Krishnamoorthy and N. Seetharaman were in the Tamil version only; Yashodhara Katju and H. K. Chopra were in the Hindi version only.[23] The entire cast was credited in the Tamil version,[3] but only six people (Rajakumari, Radha, Ranjan, Sundari Bai, Katju and L. Narayana Rao) were credited in the Hindi version; the opening titles of both versions featured a line reading "100 Gemini Boys & 500 Gemini Girls".[59]

Legacy

Sixty years ago the biggest box office hit of Tamil cinema was released. When made by the same studio in Hindi, it was so great a success that it opened up the theatres of the North to films made in the South. This is the story of the making of that film, Chandralekha.—Randor Guy[6]

With the success of Chandralekha, Vasan became known as one of the best directors in Indian cinema; he was also a member of the Rajya Sabha for one term.[6] Randor Guy later called Vasan the "Cecil B. DeMille of Tamil cinema".[5] Vasan is also believed to have inspired producer A. V. Meiyappan, who became a "master at publicity".[60] Gemini Studios published a book, Campaign, describing the making of Chandralekha.[34] Although the costliest Tamil film at that time, its box-office success opened the market for Tamil films across South India. Chandralekha demonstrated that cost should not be a constraint if a film was made and marketed well; if a film was entertaining, it would be commercially successful.[34] The publicity campaign for Chandralekha created such an impact, that Bombay-based film producers passed a resolution that there should be a limit imposed on advertisements for any film in periodicals.[61]

The film enhanced Rajakumari's and Ranjan's careers; both became popular throughout India after Chandralekha's release.[11] The film's climactic sword-fight scene was well received, and is considered the longest sword fight in cinematic history. Although it was believed that the fight scene was influenced by Scaramouche (with the longest sword fight in Hollywood history, at seven minutes), Chandralekha was made three years before Scaramouche.[62] The drum-dance sequence was considered the film's highlight,[6][11] and later producers tried to emulate it without success.[63] Chandralekha was K. Ramnoth's last film for Gemini Studios; although he is often credited with shooting the drum-dance sequence, he left Gemini in August 1947 (before the sequence was conceived).[18] In a 2011 interview with IANS, South Indian-Bollywood actress Vyjayanthimala admitted that although people consider her to have "paved the way" for other South Indian actresses in Hindi cinema, "the person who really opened the doors was S.S. Vasan". She added, "When it [Chandralekha] released, it took the north by storm because by then they haven't seen that kind of lavish sets, costumes and splendour. So Vasan was the person who opened the door for Hindi films in the south".[64]

In his interview with The Hindu, director J. Mahendran said: "If anybody tries to remake this black and white film, they will make a mockery of it".[47] Director Singeetham Srinivasa Rao told film critic Baradwaj Rangan that he disliked Chandralekha when he first saw it, realising that it was a classic only after 25 years: "a fact that the audiences realised in just two minutes."[65] G. Dhananjayan told The Times of India, "When you talk of black and white films, you cannot resist mentioning the 1948 epic Chandralekha, directed and produced by movie moghul S. S. Vasan".[66] In December 2008 S. Muthiah said, "Given how spectacular it was—and the appreciation lavished on it from 1948 till well into the 1950s, which is when I caught up with it—I'm sure that if re-released, it would do better at the box office then most Tamil films today".[5] On 26 August 2004, a postage stamp was released featuring Vasan and the drum dance to commemorate the 35th anniversary of his death.[67] Chandralekha was shown at the 10th Chennai International Film Festival in December 2012, celebrating 100 years of Indian cinema.[68][69] To celebrate the same, it was also screened at the Centenary Film Festival organised jointly by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and the National Film Archive of India, in April 2013.[70]

Notes

- ↑ The title card of the Tamil version spells Chandraleka, i.e. without the "H", so have a few other sources.[1][2] Other sources have however spelled it with the "H", such as the posters, and the title card of the Hindi version.

- ↑ In the opening titles, Kothamangalam Subbu is credited simply as "Subbu" under the "Story, Scenario and Dialogues" section, (1:30) and with his full name under the "Songs by" section (1:38).

- ↑ N. S. Krishnan was arrested on 28 December 1944 as a suspect in the Lakshmikanthan murder case.[3]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 The exchange rate in 1948 was 4.79 Indian rupees (

) per 1 US dollar (US$).[1]

) per 1 US dollar (US$).[1] - ↑ Although S. Muthiah claims that the film's first announcement came in 1943,[2] Randor Guy claims that an early advertisement for Chandralekha on the inside cover of the Nandanar song-book was published in September 1942.[3]

- ↑ G. Dhananjayan and The Times of India claim that the film was released with 609 prints worldwide,[5][6] while others claim that it was released with 603 prints.[7][8]

- ↑ The review by Dinamani is translated from Tamil to English by Dhananjayan.[4]

Bibiliography

- Srivastava, Anil and Banerjee, Shampa (1988). One Hundred Indian Feature Films: An Annotated Filmography. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-9483-2.

- Dhananjayan, G. (2011). The Best of Tamil Cinema, 1931 to 2010: 1931–1976. Galatta Media. ISBN 978-81-921043-0-0.

- Raghavendra, M. K. (2009). 50 Indian Film Classics. HarperCollins Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-81-7223-866-7.

- S. Theodore Baskaran (1996). The eye of the serpent: an introduction to Tamil cinema. East West Books.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Dhananjayan 2011, p. 92

- ↑ Gulzar, Govind Nihalani, Saibal Chatterjee (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema. Popular Prakashan. p. 432. ISBN 81-7991-066-0.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Tamil version's opening titles from 0:45 seconds to 1:20 seconds

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kanchana Devi (20 February 2012). "Tamil actress S N Lakshmi passes away". TruthDive. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 S. Muthiah (8 December 2008). "A 'Cecil B. DeMillean' Chandralekha". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 Randor Guy (December 2008). "... And thus he made Chandralekha sixty years ago". Madras Musings. XVIII. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Dhananjayan 2011, p. 93

- ↑ Tamil version's opening titles, at 1:23

- ↑ Randor Guy (26 June 2011). "Blast from the Past — Saalivaahanan 1945". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Randor Guy (29 February 2008). "Remembering Vasantha". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Randor Guy (2 October 2010). "Blast from the Past: Chandralekha (1948)". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Randor Guy (28 May 2010). "Courage goaded her on ...". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Randor Guy (24 March 2006). "Charming, villainous". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ Randor Guy (18 June 2011). "Blast from the past — Pizhaikkum Vazhi (1948)". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ S. Theodore Baskaran (2013). "The elephant in Tamil films". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ Randor Guy (5 October 2013). "The forgotten heroes". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ Randor Guy (4 August 2012). "Blast from the Past — Doctor Savithri: 1955". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Randor Guy (19 January 2013). "Blast from the Past — Rohini 1953". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ↑ N. Krishnaswamy (5 November 2004). "What made Vasan different". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ↑ Lucien Rajakarunanayake (2 June 2010). "The star trek from Chintamani to Vijay". The Sri Lanka Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Tamil version's opening titles, at 1:43

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Film News Anandan (1998). "Tamil Cinema History — The Early Days: 1945–1953". Indolink. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Paul Willemen (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. p. 310.

- ↑ Shoma A Chatterji (11 November 2006). "Sound of (background) Music". GlamSham. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Baskaran, p. 60.

- ↑ Religion and Society, Volume 12. Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society. 1965. p. 103.

- ↑ Chandralekha (DVD). Raj Video Vision. 2012.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Randor Guy (23 September 2010). "Unsung veteran of Tamil cinema". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ "Chandralekha Songs". Raaga.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ M R Venkatesh (28 July 2011). "Decoding Rajinikanth". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Tamaki Matsuoka (2008). Asia to Watch, Asia to Present: The Promotion of Asian/Indian Cinema in Japan (PDF). p. 246. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013.

- ↑ "Indiens hersker". Danish Film Institute. Archived from the original on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ G. A. Natesan (1948). "Chandraleka". The Indian Review 49: pg. 333.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5

- ↑ Prakash Chander (2003). India: Past and Present. p. 135. ISBN 81-7648-455-5.

- ↑ Ashok Da. Ranade (2006). Hindi Film Song: Music Beyond Boundaries. p. 127. ISBN 81-85002-64-9.

- ↑ Panna Shah (1950). The Indian film. Greenwood Press. pp. 83, 278.

- ↑ Sharmistha Gooptu (2011). Bengali Cinema: 'An Other Nation'. p. 85. ISBN 0-203-84334-7.

- ↑ "Box Office 1948". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grossers of Indian Cinema". IBOS Network. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Srivastava and Shampa 1988, p. 59

- ↑ S. Muthiah (26 November 2003). "Sign of the Twins". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ "A Brief History Of Tamil Cinema". Behindwoods. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ K. Jeshi (6 May 2013). "The uninvited". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ "End of the world movies". IndiaGlitz. 20 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Sangita Gopal, Sujata Moorti (2008). Global Bollywood: Travels of Hindi Song and Dance. University of Minnesota Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8166-4578-7.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 S. R. Ashok Kumar (13 July 2007). "Filmmakers' favourites". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ Raja Sen (11 May 2010). "Ten Indian classics craving digital restoration". Rediff. p. 4. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ Raghavendra, p. 36.

- ↑ Randor Guy (August 2007). "From Silents to Sivaji! A look into the past — Part II". Galatta Cinema: pg. 68.

- ↑ Jonathan Rosenbaum (20 August 1981). "August Humor". Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ K S Sivakumaran (8 June 2009). "Indian film music: An amalgam of different tunes". Daily News (Sri Lanka). Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ Jonathan Crow. "Chandralekha (1948)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ D. Devika Bai (26 October 2013). "Enduring romance with the West". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Hindi version's opening titles at 1:11

- ↑ Hindi version's opening titles at 1:16

- ↑ Hindi version's opening titles at 1:21

- ↑ "NCPA Flashback | Chandralekha". National Centre for the Performing Arts (India). Mumbai. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ Hindi version's opening titles at 0:45 seconds

- ↑ Bhama Devi Ravi (8 August 2008). "Kollywood turns to coffee-table books". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ David Blamey, Robert D'Souza, Sara Dickey (2005). Living Pictures: Perspectives on the Film Poster in India. Open Editions. p. 57.

- ↑ J. Vasanthan (16 July 2005). "Heroines of the past". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ Gokulsing, K.; Moti Gokulsing, Wimal (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. p. 49. ISBN 1-85856-329-1.

- ↑ "Camera does wonders today: Vyjayanthimala". India Today. IANS. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Baradwaj Rangan (4 November 2011). "Lights, Camera, Conversation ..."Crouched around a campfire storyteller"". Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ M. Suganth (2 March 2012). "Black and white films in Kollywood". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ "Stamp on S.S. Vasan released". The Hindu. 27 August 2004. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ Sudhish Kamath (3 December 2012). "Showcase of the best". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "Big B comes to Chennai". Behindwoods. 20 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Henna Rakheja (30 April 2013). "Films that saw it all over 100 years". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

External links

- Chandralekha at the Internet Movie Database

- Chandra (English version) at the Internet Movie Database

- Chandralekha at Rotten Tomatoes

- Chandralekha at Upperstall.com

- Chandralekha at Bollywood Hungama