Center of mass

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. The distribution of mass is balanced around the center of mass and the average of the weighted position coordinates of the distributed mass defines its coordinates. Calculations in mechanics are often simplified when formulated with respect to the center of mass.

In the case of a single rigid body, the center of mass is fixed in relation to the body, and if the body has uniform density, it will be located at the centroid. The center of mass may be located outside the physical body, as is sometimes the case for hollow or open-shaped objects, such as a horseshoe. In the case of a distribution of separate bodies, such as the planets of the Solar System, the center of mass may not correspond to the position of any individual member of the system.

The center of mass is a useful reference point for calculations in mechanics that involve masses distributed in space, such as the linear and angular momentum of planetary bodies and rigid body dynamics. In orbital mechanics, the equations of motion of planets are formulated as point masses located at the centers of mass. The center of mass frame is an inertial frame in which the center of mass of a system is at rest at with respect the origin of the coordinate system.

History

The concept of "center of mass" in the form of the "center of gravity" was first introduced by the ancient Greek physicist, mathematician, and engineer Archimedes of Syracuse. He worked with simplified assumptions about gravity that amount to a uniform field, thus arriving at the mathematical properties of what we now call the center of mass. Archimedes showed that the torque exerted on a lever by weights resting at various points along the lever is the same as what it would be if all of the weights were moved to a single point — their center of mass. In work on floating bodies he demonstrated that the orientation of a floating object is the one that makes its center of mass as low as possible. He developed mathematical techniques for finding the centers of mass of objects of uniform density of various well-defined shapes.[1]

Later mathematicians who developed the theory of the center of mass include Pappus of Alexandria, Guido Ubaldi, Francesco Maurolico,[2] Federico Commandino,[3] Simon Stevin,[4] Luca Valerio,[5] Jean-Charles de la Faille, Paul Guldin,[6] John Wallis, Louis Carré, Pierre Varignon, and Alexis Clairaut.[7]

Newton's second law is reformulated with respect to the center of mass in Euler's first law.[8]

Definition

The center of mass is the unique point at the center of a distribution of mass in space that has the property that the weighted position vectors relative to this point sum to zero. In analogy to statistics, the center of mass is the mean location of a distribution of mass in space.

A system of particles

In the case of a system of particles Pi, i = 1, …, n , each with mass mi that are located in space with coordinates ri, i = 1, …, n , the coordinates R of the center of mass satisfy the condition

Solve this equation for R to obtain the formula

where M is the sum of the masses of all of the particles.

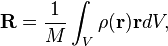

A continuous volume

If the mass distribution is continuous with the density ρ(r) within a volume V, then the integral of the weighted position coordinates of the points in this volume relative to the center of mass R is zero, that is

Solve this equation for the coordinates R to obtain

where M is the total mass in the volume.

If a continuous mass distribution has uniform density, which means ρ is constant, then the center of mass is the same as the centroid of the volume.[9] The center of mass is not the point at which a plane separates the distribution of mass into two equal halves. In analogy with statistics, the median is not the same as the mean.

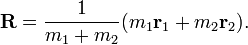

Barycentric coordinates

The coordinates R of the center of mass of a two-particle system, P1 and P2, with masses m1 and m2 is given by

Let the percentage of the total mass divided between these two particles vary from 100% P1 and 0% P2 through 50% P1 and 50% P2 to 0% P1 and 100% P2, then the center of mass R moves along the line from P1 to P2. The percentages of mass at each point can be viewed as projective coordinates of the point R on this line, and are termed barycentric coordinates. Another way of interpreting the process here is the mechanical balancing of moments about an arbitrary datam. The numerator gives the total moment which is then balanced by an equivalent total force at the center of mass. This can be generalized to three points and four points to define projective coordinates in the plane, and in space, respectively.

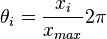

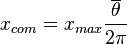

Systems with periodic boundary conditions

For particles in a system with periodic boundary conditions two particles can be neighbors even though they are on opposite sides of the system. This occurs often in molecular dynamics simulations, for example, in which clusters form at random locations and sometimes neighboring atoms cross the periodic boundary. When a cluster straddles the periodic boundary, a naive calculation of the center of mass will be incorrect. A generalized method for calculating the center of mass for periodic systems is to treat each coordinate, x and y and/or z, as if it were on a circle instead of a line.[10] The calculation takes every particle's x coordinate and maps it to an angle,

where xmax is the system size in the x direction. From this angle, two new points  can be generated:

can be generated:

In the  plane, these coordinates lie on a circle of radius xmax. From the collection of

plane, these coordinates lie on a circle of radius xmax. From the collection of  and

and  values from all the particles, the averages

values from all the particles, the averages  and

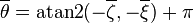

and  are calculated. These values are mapped back into a new angle,

are calculated. These values are mapped back into a new angle,  , from which the x coordinate of the center of mass can be obtained:

, from which the x coordinate of the center of mass can be obtained:

The process can be repeated for all dimensions of the system to determine the complete center of mass. The utility of the algorithm is that it allows the mathematics to determine where the "best" center of mass is, instead of guessing or using cluster analysis to "unfold" a cluster straddling the periodic boundaries. It must be noted that if both average values are zero,  , then

, then  is undefined. This is a correct result, because it only occurs when all particles are exactly evenly spaced. In that condition, their x coordinates are mathematically identical in a periodic system.

is undefined. This is a correct result, because it only occurs when all particles are exactly evenly spaced. In that condition, their x coordinates are mathematically identical in a periodic system.

Center of gravity

Center of gravity is the point in a body around which the resultant torque due to gravity forces vanish. Near the surface of the earth, where the gravity acts downward as a parallel force field, the center of gravity and the center of mass are the same.

The study of the dynamics of aircraft, vehicles and vessels assumes that the system moves in near-earth gravity, and therefore the terms center of gravity and center of mass are used interchangeably.

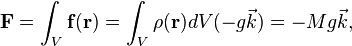

In physics the benefits of using the center of mass to model a mass distribution can be seen by considering the resultant of the gravity forces on a continuous body. Consider a body of volume V with density ρ(r) at each point r in the volume. In a parallel gravity field the force f at each point r is given by,

where dm is the mass at the point r, g is the acceleration of gravity, and k is a unit vector defining the vertical direction. Choose a reference point R in the volume and compute the resultant force and torque at this point,

and

If the reference point R is chosen so that it is the center of mass, then

which means the resultant torque T=0. Because the resultant torque is zero the body will move as though it is a particle with its mass concentrated at the center of mass.

By selecting the center of gravity as the reference point for a rigid body, the gravity forces will not cause the body to rotate, which means weight of the body can be considered to be concentrated at the center of mass.

Linear and angular momentum

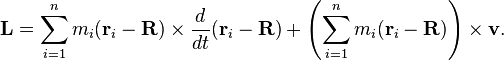

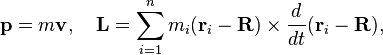

The linear and angular momentum of a collection of particles can be simplified by measuring the position and velocity of the particles relative to the center of mass. Let the system of particles Pi, i=1,...,n of masses mi be located at the coordinates ri with velocities vi. Select a reference point R and compute the relative position and velocity vectors,

The total linear and angular momentum vectors relative to the reference point R are

and

If R is chosen as the center of mass these equations simplify to

where m is the total mass of all the particles, p is the linear momentum, and L is the angular momentum.

Newton's laws of motion require that for any system with no external forces the momentum of the system is constant, which means the center of mass moves with constant velocity. This applies for all systems with classical internal forces, including magnetic fields, electric fields, chemical reactions, and so on. More formally, this is true for any internal forces that satisfy Newton's Third Law.[11]

Locating the center of mass

The experimental determination of the center of mass of a body uses gravity forces on the body and relies on the fact that in the parallel gravity field near the surface of the earth the center of mass is the same as the center of gravity.

The center of mass of a body with an axis of symmetry and constant density must lie on this axis. Thus, the center of mass of a circular cylinder of constant density has its center of mass on the axis of the cylinder. In the same way, the center of mass of a spherically symmetric body of constant density is at the center of the sphere. In general, for any symmetry of a body, its center of mass will be a fixed point of that symmetry.[12]

In two dimensions

An experimental method for locating the center of mass is to suspend the object from two locations and to drop plumb lines from the suspension points. The intersection of the two lines is the center of mass.[13]

The shape of an object might already be mathematically determined, but it may be too complex to use a known formula. In this case, one can subdivide the complex shape into simpler, more elementary shapes, whose centers of mass are easy to find. If the total mass and center of mass can be determined for each area, then the center of mass of the whole is the weighted average of the centers.[14] This method can even work for objects with holes, which can be accounted for as negative masses.[15]

A direct development of the planimeter known as an integraph, or integerometer, can be used to establish the position of the centroid or center of mass of an irregular two-dimensional shape. This method can be applied to a shape with an irregular, smooth or complex boundary where other methods are too difficult. It was regularly used by ship builders to compare with the required displacement and centre of buoyancy of a ship, and ensure it would not capsize.[16][17]

In three dimensions

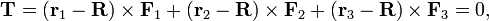

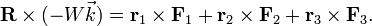

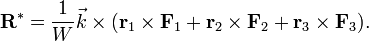

An experimental method to locate the three dimensional coordinates of the center of mass begins by supporting the object at three points and measuring the forces, F1, F2, and F3 that resist the weight of the object, W= −Wk (k is the unit vector in the vertical direction). Let r1, r2, and r3 be the position coordinates of the support points, then the coordinates R of the center of mass satisfy the condition that the resultant torque is zero,

or

This equation yields the coordinates of the center of mass R* in the horizontal plane as,

The center of mass lies on the vertical line L, given by

The three dimensional coordinates of the center of mass are determined by performing this experiment twice with the object positioned so that these forces are measured for two different horizontal planes through the object. The center of mass will be the intersection of the two lines L1 and L2 obtained from the two experiments.

Applications

Engineers try to design a sports car so that its center of mass is lowered to make the car handle better. When high jumpers perform a "Fosbury Flop", they bend their body in such a way that it clears the bar while its center of mass does not necessarily clear it.[18]

Aeronautics

The center of mass is an important point on an aircraft, which significantly affects the stability of the aircraft. To ensure the aircraft is stable enough to be safe to fly, the center of mass must fall within specified limits. If the center of mass is ahead of the forward limit, the aircraft will be less maneuverable, possibly to the point of being unable to rotate for takeoff or flare for landing.[19] If the center of mass is behind the aft limit, the aircraft will be more maneuverable, but also less stable, and possibly so unstable that it is impossible to fly. The moment arm of the elevator will also be reduced, which makes it more difficult to recover from a stalled condition.[20]

For helicopters in hover, the center of mass is always directly below the rotorhead. In forward flight, the center of mass will move forward to balance the negative pitch torque produced by applying cyclic control to propel the helicopter forward; consequently a cruising helicopter flies "nose-down" in level flight.[21]

Astronomy

The center of mass plays an important role in astronomy and astrophysics, where it is commonly referred to as the barycenter. The barycenter is the point between two objects where they balance each other; it is the center of mass where two or more celestial bodies orbit each other. When a moon orbits a planet, or a planet orbits a star, both bodies are actually orbiting around a point that lies away from the center of the primary (larger) body.[22] For example, the Moon does not orbit the exact center of the Earth, but a point on a line between the center of the Earth and the Moon, approximately 1,710 km (1062 miles) below the surface of the Earth, where their respective masses balance. This is the point about which the Earth and Moon orbit as they travel around the Sun. If the masses are more similar, e.g., Pluto and Charon, the barycenter will fall outside both bodies.

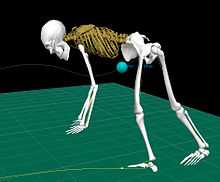

Kinesiology

In kinesiology and biomechanics, the center of mass is an important parameter that assists people in understanding human locomotion. The human body’s center of mass is always changing because it is not a fixed shape. Typically, a human’s center of mass is detected with a reaction board or the segmentation method. The reaction board is a static analysis that involves the person lying down on the reaction board, and using the static equilibrium equation to find the center of mass. The segmentation method is a mathematic solution that states that the summation of the torques of individual body sections relative to a specified axis must equal the torque of the whole body system relative to the same axis.[23]

See also

- Expected value

- Center of mass (relativistic)

- Center of percussion

- Center of pressure (fluid mechanics)

- Center of pressure (terrestrial locomotion)

- Centroid

- Mass point geometry

- Metacentric height

- Roll center

- Weight distribution

Notes

- ↑ Shore 2008, pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Baron 2004, pp. 91–94.

- ↑ Baron 2004, pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Baron 2004, pp. 96–101.

- ↑ Baron 2004, pp. 101–106.

- ↑ Mancosu 1999, pp. 56–61.

- ↑ Walton 1855, p. 2.

- ↑ Beatty 2006, p. 29.

- ↑ Levi 2009, p. 85.

- ↑ Bai, Linge; Breen, David (2008). "Calculating Center of Mass in an Unbounded 2D Environment". Journal of Graphics, GPU, and Game Tools 13 (4): 53–60. doi:10.1080/2151237X.2008.10129266.

- ↑ Kleppner & Kolenkow 1973, p. 117.

- ↑ Feynman, Leighton & Sands 1963, p. 19.3.

- ↑ Kleppner & Kolenkow 1973, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Feynman, Leighton & Sands 1963, pp. 19.1–19.2.

- ↑ Hamill 2009, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ "The theory and design of British shipbuilding. (page 3 of 14)". Amos Lowrey Ayre. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ↑ Sangwin 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ Van Pelt 2005, p. 185.

- ↑ Federal Aviation Administration 2007, p. 1.4.

- ↑ Federal Aviation Administration 2007, p. 1.3.

- ↑ "Helicopter Aerodynamics". p. 82. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ Murray & Dermott 1999, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Vint 2003, pp. 1–11.

References

- Baron, Margaret E. (2004) [1969], The Origins of the Infinitesimal Calculus, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-49544-2

- Beatty, Millard F. (2006), Principles of Engineering Mechanics, Volume 2: Dynamics—The Analysis of Motion, Mathematical Concepts and Methods in Science and Engineering 33, Springer, ISBN 0-387-23704-6

- Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert; Sands, Matthew (1963), The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Addison Wesley, ISBN 0-201-02116-1

- Federal Aviation Administration (2007), Aircraft Weight and Balance Handbook, United States Government Printing Office, retrieved 23 October 2011

- Giambattista, Alan; Richardson, Betty McCarthy; Richardson, Robert Coleman (2007), College physics, Volume 1 (2nd ed.), McGraw-Hill Higher Education, ISBN 0-07-110608-1

- Goldstein, Herbert; Poole, Charles; Safko, John (2001), Classical Mechanics (3rd ed.), Addison Wesley, ISBN 0-201-65702-3

- Hamill, Patrick (2009), Intermediate Dynamics, Jones & Bartlett Learning, ISBN 978-0-7637-5728-1

- Kleppner, Daniel; Kolenkow, Robert (1973), An Introduction to Mechanics (2nd ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-035048-5

- Levi, Mark (2009), The Mathematical Mechanic: Using Physical Reasoning to Solve Problems, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14020-9

- Mancosu, Paolo (1999), Philosophy of mathematics and mathematical practice in the seventeenth century, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513244-0

- Murray, Carl; Dermott, Stanley (1999), Solar System Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-57295-9

- Sangwin, Christopher J. (2006), "Locating the centre of mass by mechanical means", Journal of the Oughtred Society 15 (2), retrieved 23 October 2011

- Shore, Steven N. (2008), Forces in Physics: A Historical Perspective, Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-33303-3

- Symon, Keith R. (1971), Mechanics (3rd ed.), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-07392-7

- Van Pelt, Michael (2005), Space Tourism: Adventures in Earth Orbit and Beyond, Springer, ISBN 0-387-40213-6

- Walton, William (1855), A collection of problems in illustration of the principles of theoretical mechanics (2nd ed.), Deighton, Bell & Co.

- Asimov, Isaac (1988) [1966], Understanding Physics, Barnes & Noble Books, ISBN 0-88029-251-2

- Beatty, Millard F. (2006), Principles of Engineering Mechanics, Volume 2: Dynamics—The Analysis of Motion, Mathematical Concepts and Methods in Science and Engineering 33, Springer, ISBN 0-387-23704-6

- Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (1963), The Feynman Lectures on Physics 1 (Sixth printing, February 1977 ed.), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-02010-6H Check

|isbn=value (help) - Frautschi, Steven C.; Olenick, Richard P.; Apostol, Tom M.; Goodstein, David L. (1986), The Mechanical Universe: Mechanics and heat, advanced edition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30432-6

- Goldstein, Herbert; Poole, Charles; Safko, John (2002), Classical Mechanics (3rd ed.), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-65702-3

- Goodman, Lawrence E.; Warner, William H. (2001) [1964], Statics, Dover, ISBN 0-486-42005-1

- Hamill, Patrick (2009), Intermediate Dynamics, Jones & Bartlett Learning, ISBN 978-0-7637-5728-1

- Jong, I. G.; Rogers, B. G. (1995), Engineering Mechanics: Statics, Saunders College Publishing, ISBN 0-03-026309-3

- Millikan, Robert Andrews (1902), Mechanics, molecular physics and heat: a twelve weeks' college course, Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, retrieved 25 May 2011

- Pollard, David D.; Fletcher, Raymond C. (2005), Fundamentals of Structural Geology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-83927-0

- Pytel, Andrew; Kiusalaas, Jaan (2010), Engineering Mechanics: Statics 1 (3rd ed.), Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-0-495-29559-4

- Rosen, Joe; Gothard, Lisa Quinn (2009), Encyclopedia of Physical Science, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7011-4

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2006), Principles of physics: a calculus-based text 1 (4th ed.), Thomson Learning, ISBN 0-534-49143-X

- Shirley, James H.; Fairbridge, Rhodes Whitmore (1997), Encyclopedia of planetary sciences, Springer, ISBN 0-412-06951-2

- De Silva, Clarence W. (2002), Vibration and shock handbook, CRC Press, ISBN 978-0-8493-1580-0

- Symon, Keith R. (1971), Mechanics, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-07392-8

- Tipler, Paul A.; Mosca, Gene (2004), Physics for Scientists and Engineers 1A (5th ed.), W. H. Freeman and Company, ISBN 0-7167-0900-7

- Vint, Peter (2003), "LAB: Center of Mass (Center of Gravity) of the Human Body", KIN 335 - Biomechanics, retrieved 18 October 2013

External links

| Look up barycentre in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Motion of the Center of Mass shows that the motion of the center of mass of an object in free fall is the same as the motion of a point object.

- The Solar System's barycenter, simulations showing the effect each planet contributes to the Solar System's barycenter.

- Center of Gravity at Work, video showing bjects climbing up an incline by themselves.

| ||||||||