Cavity opto-mechanics

Cavity opto-mechanics is a branch of physics which focusses on the interaction between light and mechanical objects on low-energy scales. It is a cross field of optics, quantum optics, solid-state physics and materials science. The motivation for research on cavity optomechanics comes from fundamental effects of quantum theory and gravity, as well as technological applications.

The name of the field relates to the main effect of interest, which is the enhancement of radiation pressure interaction between light (photons) and matter using optical resonators (cavities). One may envision optomechanical structures to allow the realization of Schrödinger's cat. Macroscopic objects consisting of billions of atoms share collective degrees of freedom which may behave quantum mechanically, e.g. a sphere of micrometer diameter being in a spatial superposition between two different places. Such a quantum state of motion would allow to experimentally investigate decoherence, which describes the process of objects transitioning between states which are described by quantum mechanics to states which are described by Newtonian mechanics. Optomechanical structures pave a new way for testing the predictions of quantum mechanics and decoherence models and thereby might allow to answer some of the most fundamental questions in modern physics.

There is a broad range of experimental optomechanical systems which are almost equivalent in their description, but completely different in size, mass and frequency, ranging from attograms and gigahertz to kilograms and hertz. Cavity optomechanics was featured as the most recent milestone of photon history[1] in nature photonics along well established concepts and technology like Quantum information, Bell inequalities and the laser.

Concepts of cavity opto-mechanics

According to the quantum theory of light, every photon with wave number  carries a momentum

carries a momentum  with Planck's constant

with Planck's constant  and the speed of light

and the speed of light  . This means that a photon which is reflected of a mirror surface transfers a momentum

. This means that a photon which is reflected of a mirror surface transfers a momentum  onto the mirror, since the net momentum has to be conserved. This effect is extremely small and can not be observed on most every-day objects, however it becomes bigger when the mass of the mirror is very small.

onto the mirror, since the net momentum has to be conserved. This effect is extremely small and can not be observed on most every-day objects, however it becomes bigger when the mass of the mirror is very small.

Photons can be prepared in quantum (non-classical) states. If one assumes that quantum mechanics also describes the physics of the motion of a small mirror, it should be possible to use quantum states of photons to create quantum states of mirrors. Compared to most "typical" quantum objects like photons, electrons, atoms and small molecules, even a nanogram mirror which can just be seen under a microscope is larger by many orders of magnitude. This makes optomechanical structures the closest experimental neighbours to the quantum cat in Schrödinger's Gedankenexperiment.

Enhancing the interaction between light and matter with optical cavities

Since the momentum of photons is extremely small and not enough to change the position of a suspended mirror by more than its quantum mechanical position uncertainty, one needs to enhance the interaction. One possible way to do this is by using optical cavities. If a photon is enclosed between two mirrors, one being the oscillator and the other a heavy fixed one, it will bounce off the mirrors many times and transfer its momentum every time it hits the mirrors. The number of times a photon can transfer its momentum is directly related to the finesse of the cavity, which can be improved with highly reflective mirror surfaces.

Another advantage of optical cavities is that the modulation of the cavity length through an oscillating mirror can directly be seen in the spectrum of the cavity. The mechanics produce red and blue sidebands around the optical resonances, shifted by the mechanical frequency. These sidebands can then be used for optical cooling of the mechanical oscillator: By detuning incoming light from resonance to the red sideband, the photons can only enter the cavity if they take phonons with energy  from the mechanics. This effectively cools the device until a balance with heating mechanisms from the environment and laser noise is reached. Cavity cooling has successfully been used to cool devices to the quantum ground state. In the same fashion it is also possible to heat structures by detuning a laser to the blue side and thereby achieving strong accelerations in the mechanical oscillator.

from the mechanics. This effectively cools the device until a balance with heating mechanisms from the environment and laser noise is reached. Cavity cooling has successfully been used to cool devices to the quantum ground state. In the same fashion it is also possible to heat structures by detuning a laser to the blue side and thereby achieving strong accelerations in the mechanical oscillator.

There are several different ways of applying cavities around optomechanical structures. In the reflective case the mechanical structure of interest is one end mirror of the cavity (or the whole cavity itself is a mechanical oscillator). In the dispersive case, a dispersive medium is brought into a cavity consisting of fixed massive mirrors. Both schemes are similar, though not entirely equivalent.[2] A third way of achieving coupling between mechanical structures and the light field within a cavity is through evanescent fields.[3]

Mathematical treatment

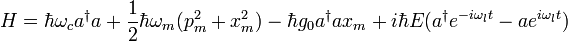

The full hamiltonian of the system can be motivated to be of the following form:[4]

with the cavity frequency  , the annihilation and creation operators of the cavity field

, the annihilation and creation operators of the cavity field  and

and  , the momentum and position operators of the mechanics

, the momentum and position operators of the mechanics  and

and  , the coupling rate

, the coupling rate  , the laser input

, the laser input  and frquency

and frquency  .

.

Relation to fundamental research

One of the questions which are still subject to current debate is the exact mechanism of decoherence. As Schrödinger pointed out, we would never see something like a cat in a quantum state. There needs to be something like a collapse of the quantum wave functions, which brings it from a quantum state to a pure classical state. Now one can ask where the boundary lies between objects with quantum properties and classical objects. Taking spatial superpositions as an example, there might be a size limit to objects which can be brought into superpositions, there might be a limit to the spatial separation of the centers of mass a super position or even a limit to the superposition of gravitational fields and its impact on small test masses. Those predictions could be checked with large mechanical structures which can be manipulated on a quantum level.[5]

Some easier to check predictions of quantum mechanics is the prediction of negative Wigner functions for certain quantum states,[6] measurement precision beyond the standard quantum limit using squeezed states of light[7] or the asymmetry of the sidebands in the spectrum of a cavity near the quantum ground state.[8]

Applications

Years before cavity opto-mechanics gained the status of an independent field of research, many of its techniques were already used in Gravitational wave detectors where it is necessary to measure displacements of mirrors on the order of the Planck scale. Even if these detectors do not address the measurement of quantum effects, they encounter related issues (photon shot noise) and use similar tricks (squeezed states) to enhance the precision. Further applications include the development of quantum memory for quantum computers[9] and high precision acceleration sensors.[10]

Neighbouring fields

Cavity opto-meachnics is closely related to trapped ion physics and Bose-Einstein condensates. These systems share very similar Hamiltonians, but they have less particles (about 10 for ion traps and  -

- for BECs) interacting with the field of light.

for BECs) interacting with the field of light.

See also

- Radiation pressure

- Quantum optics

- Ground state

- Quantum harmonic oscillator

- Solid-state physics

- Optical cavity

- Schrödinger's cat

- Decoherence

References

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/milestones/milephotons/full/milephotons23.html

- ↑ Thompson, J. D., Zwickl, B. M., Jayich, A. M., Marquardt, F., Girvin, S. M., & Harris, J. G. E. (2008). Strong dispersive coupling of a high-finesse cavity to a micromechanical membrane. Nature, 452(7183), 72-5. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/nature06715

- ↑ Anetsberger, G., Arcizet, O., Unterreithmeier, Q. P., Rivière, R., Schliesser, A., Weig, E. M., Kotthaus, J. P., et al. (2009). Near-field cavity optomechanics with nanomechanical oscillators. Nature Physics, 5(12), 909-914. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/nphys1425

- ↑ Law, C. (1994). Effective Hamiltonian for the radiation in a cavity with a moving mirror and a time-varying dielectric medium. Physical Review A, 49(1), 433-437. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.49.433

- ↑ Bose, S., Jacobs, K., & Knight, P. (1999). Scheme to probe the decoherence of a macroscopic object. Physical Review A, 59(5), 3204-3210. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.59.3204

- ↑ Simon Rips, Martin Kiffner, Ignacio Wilson-Rae, & Michael Hartmann. (2011). Cavity Optomechanics with Nonlinear Mechanical Resonators in the Quantum Regime - OSA Technical Digest (CD). CLEO/Europe and EQEC 2011 Conference Digest (p. JSI2_3). Optical Society of America. Retrieved from http://www.opticsinfobase.org/abstract.cfm?URI=EQEC-2011-JSI2_3

- ↑ Jaekel, M. T., & Reynaud, S. (1990). Quantum Limits in Interferometric Measurements. Europhysics Letters (EPL), 13(4), 301-306. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/13/4/003

- ↑ Safavi-Naeini, A. H., Chan, J., Hill, J. T., Alegre, T. P. M., Krause, A., & Painter, O. (2011). Measurement of the quantum zero-point motion of a nanomechanical resonator, 6. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1108.4680

- ↑ Cole, G. D., & Aspelmeyer, M. (2011). Cavity optomechanics: Mechanical memory sees the light. Nature nanotechnology, 6(11), 690-1. Nature Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. doi:10.1038/nnano.2011.199

- ↑ Krause, A. G., Winger, M., Blasius, T. D., Lin, Q. & Painter, O. A high-resolution microchip optomechanical accelerometer. Nature Photonics (2012). doi:10.1038/nphoton.2012.245

Further reading

- Aspelmeyer, M., Gröblacher, S., Hammerer, K., & Kiesel, N. (2010). Quantum optomechanics—throwing a glance [Invited]. Journal of the Optical Society of America B, 27(6), A189. OSA. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.27.00A189

- Kippenberg, T. J., & Vahala, K. J. (2007). Cavity Opto-Mechanics. Optics Express, 15(25), 17172. OSA. doi:10.1364/OE.15.017172

- Romero-Isart, O., Pflanzer, A., Blaser, F., Kaltenbaek, R., Kiesel, N., Aspelmeyer, M., & Cirac, J. (2011). Large Quantum Superpositions and Interference of Massive Nanometer-Sized Objects. Physical Review Letters, 107(2). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.020405