Catenaccio

Catenaccio (Italian pronunciation: [ka-te-nacho]) or The Chain is a tactical system in football with a strong emphasis on defense. In Italian, catenaccio means "door-bolt", which implies a highly organized and effective backline defense focused on nullifying opponents' attacks and preventing goal-scoring opportunities.

History

The system was made famous by the Franco-Argentine trainer Helenio Herrera of Internazionale in the 1960s who used it to grind out small-score wins, such as 1–0 or 2–1, over opponents in their games.[1][2]

The Catenaccio was influenced by the verrou (also "doorbolt/chain" in French) system invented by Austrian coach Karl Rappan.[3] As coach of Switzerland in the 1930s and 1940s, Rappan played a defensive sweeper called the verrouilleur, who was highly defensive and was positioned just ahead of the goalkeeper.[4] In the 1950s, Nereo Rocco's Padova pioneered the system in Italy where it would be used again by the Internazionale team of the early 1960s.[5][6]

Rappan's verrou system, proposed in 1932, when he was coach of Servette, was implemented with four fixed defenders, playing a strict man-to-man marking system, plus a playmaker in the middle of the field who played the ball together with two midfield wings.

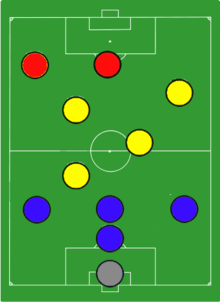

Rocco's tactic, often referred to as the "real" Catenaccio, was shown first in 1947 with Triestina: the most common mode of operation was a 1–3–3–3 formation with a strictly defensive team approach. With catenaccio, Triestina finished the Serie A tournament in a surprising second place. Some variations include 1–4–4–1 and 1–4–3–2 formations.

The key innovation of Catenaccio was the introduction of the role of a libero ("free") defender, also called "sweeper", who was positioned behind a line of three defenders. The sweeper's role was to recover loose balls, nullify the opponent's striker and double-mark when necessary. Another important innovation was the counter-attack, mainly based on long passes from the defence.

In Herrera's version in the 1960s, four man-marking defenders were tightly assigned to each opposing attacker while an extra sweeper would pick up any loose ball that escaped the coverage of the defenders. The emphasis of this system in Italian football spawned the rise of many top Italian defenders who became known for their hard-tackling, ruthless defending. Defenders such as Claudio Gentile and Gaetano Scirea in the 1970s, Giuseppe Bergomi and Franco Baresi in the 1980s, the famous all-Italian Milan defensive four of Franco Baresi, Paolo Maldini, Alessandro Costacurta and Mauro Tassotti of the 1990s and 2006 World Cup winners Fabio Cannavaro and Alessandro Nesta and many others in 2000s formed the backbone of the Italian national team and also played vital roles in the success of their respective Serie A clubs. However, despite the defensive connotations, Herrera claimed shortly before his death that the system was more attacking than people remembered, saying 'the problem is that most of the people who copied me copied me wrongly. They forgot to include the attacking principles that my Catenaccio included. I had Picchi as a sweeper, yes, but I also had Facchetti, the first full back to score as many goals as a forward.'

Zona Mista

Total Football, invented by Rinus Michels in the 1970s, rendered Herrera's version of Catenaccio rather obsolete. In Total Football, no player is fixed in his nominal role; anyone can assume in the field the duties of an attacker, a midfielder or a defender, depending on the play. Man-marking alone was insufficient to cope with this fluid system. Coaches began to create a new tactical system that mixed man-marking with zonal defense. In 1972, Michels' Ajax defeated Herrera's Inter 2–0 in the European Cup final and Dutch newspapers announced the "destruction of Catenaccio" at the hands of Total Football.[7] In 1973, Ajax crushed Cesare Maldini's Milan 6–0 for the European Super Cup in a match in which the defensive Milan system was destroyed by Ajax.

In pure zonal defense, every midfielder and defender is given a particular zone on the field to cover. When a player moves outside his zone, his teammate expands his zone to cover the unmarked area. However, Catenaccio philosophy called for double-marking when dealing with strong players. Zona Mista (Italian for "mixed zone") was created by Enzo Bearzot combining the strength of zonal marking with that of Catenaccio.[8]

In Zona Mista (or Il gioco all'Italiana: "The Game in the Italian style"), there are four defenders. A sweeper is free to roam and assist other defenders. A fullback plays in both defensive and advanced position, typically on the left flank. The two stoppers, who started then to be called "centre back", mark their zones. In the midfield, there are defensive midfielder, centre midfielder and the playmaker (the number 10) and a winger who covers typically the right flank and sometimes acts as an additional striker. Zona Mista employs two-prong attack. A centre forward plays upfront. A second striker plays wide to the left (a derivation of Catenaccio's left winger) and drift inside to act as a striker or to cover the playmaker when the playmaker drops into a defensive position.

Zona Mista came to dominate Italian football in the late 1970s and early 1980s and reached its height with the Italian national team in their victory in the 1982 FIFA World Cup.[9] Classy and skillful Gaetano Scirea was the libero, Fulvio Collovati and tough tackling Claudio Gentile the centre backs, Antonio Cabrini the left wingback. Gabriele Oriali played as a holding midfielder, Marco Tardelli centre midfielder and Giancarlo Antognoni as playmaker.

The popularity of Zona Mista, however, eventually led to its undoing as Italian teams became predictable. Hamburg would expose the predictability of this style against Juventus in the 1983 European Cup Final and took control of the game accordingly.[9]

Catenaccio today

Real Catenaccio is no longer used in the modern football world. Two major characteristics of this style – the man-to-man marking and the libero ("free") position – are no longer in use. Highly defensive structures with little attacking intent are often labeled as Catenaccio, but deviates from the original design of the system. Modern teams have all moved away from man-marking defensive schemes in favor of zonal marking systems.[10] Moreover, the sweeper or libero position has virtually disappeared from the modern game since the 1980s because teams favored deploying the extra man in another area of the pitch.[11]

Many journalists and coaches have called that style of play a brilliant counterattacking style.[12][13]

Catenaccio is often thought to be commonplace in Italian football;[14] however, it is actually used infrequently by Italian Serie A teams, who instead prefer to apply balanced tactics and formations, mostly 4–3–3 or 3–5–2,[15] The Italian national football team with manager Cesare Prandelli also used the 3-5-2 in their first clashes of UEFA Euro 2012 Group C and then switched to the their 'standard' 4–4–2 formation UEFA Euro 2012 final. Italy's previous coaches, Cesare Maldini and Giovanni Trapattoni, used the Catenaccio at international level,[16][17] and both failed to reach the top. Italy, under Maldini, lost on penalties at the 1998 FIFA World Cup quarter-finals, while Trapattoni lost early in the second round at 2002 FIFA World Cup and lost at the UEFA Euro 2004 during the first round.

However, Catenaccio has also had its share of success stories. Trapattoni himself successfully employed it in securing a Portuguese Liga title with Benfica in 2005. German coach Otto Rehhagel also used a similarly defensive approach for his Greece national football team in UEFA Euro 2004, going on to win the tournament despite his team being heavy underdogs.[18] Dino Zoff also put Catenaccio to good use for Italy, securing a place in the UEFA Euro 2000 final, which Italy only lost on the "golden goal" rule to France. Likewise, Azeglio Vicini led Italy to the 1990 FIFA World Cup semifinal thanks to small wins in six hard-fought defensive games in which Italy produced little but risked even less, totaling only 7 goals for and none against. Italy would then lose a tight semifinal to Argentina, due in no small part to a similar strategy from Carlos Bilardo, who then went on to lose the final to a much more offensive-minded Germany led by Franz Beckenbauer.[citation needed]

Similarly, when Italy was reduced to 10 men in the 50th minute of the 2006 FIFA World Cup 2nd round match against Australia, coach Marcello Lippi changed the Italian's formation to a defensive orientation which caused the British newspaper The Guardian to note that "the timidity of Italy's approach had made it seem that Helenio Herrera, the high priest of Catenaccio, had taken possession of the soul of Marcello Lippi." It should be noted, however, that the ten-man team was playing with a 4–3–2 scheme, just a midfielder away from the regular 4–4–2.[19]

After the 2006 World Cup, the media picked up the fact that modern international football is becoming increasingly defensive: the number of goals scored in that World Cup was only 147 (an average of 2.297 per match), and the Golden Boot winner Miroslav Klose only scored five goals[20] as opposed to the eight of the previous winner, Ronaldo.[21] Additionally, the 2006 World Cup was the first not to feature any forwards in its official top-three "Best Players".[citation needed]

See also

- Striker

- Football (soccer)

- Total Football

- Football tactics and skills

- Formation (football)

Notes

- ↑ fifa.com Mazzola: Inter is my second family

- ↑ about.com Catenaccio - The Lost Art Of Defensive Football

- ↑ "Background on the Intertoto Cup". Mogiel.net. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ Andy Gray with Jim Drewett. Flat Back Four: The Tactical Game. Macmillan Publishers Ltd, London, 1998.

- ↑ cbcsports.com 1962 Chile

- ↑ fifa.com Intercontinental Cup 1969

- ↑ "Season 1971-72". European Cup History. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- ↑ "Enzo Bearzot". Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Italy 3-2 Brazil, 1982: the day naivety, not football itself, died". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ↑ "The Question: Position or possession?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ↑ "The Question: Could the sweeper be on his way back?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ↑ "Mou y el antifútbol". Mundodeportivo.com. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ "Blog Gente Blaugrana - Deportes". Es.eurosport.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ David Hytner (2012-12-17). "Santi Cazorla's hat-trick at Reading gives Arsène Wenger breathing space". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-01-04.

- ↑ Will Tidey (2012-08-08). "4-2-3-1 Is the New Normal, but Is Serie A's 3-5-2 the Antidote?". BleacherReport.com. Retrieved 2013-01-04.

- ↑ "Mondiali: Trapattoni, "Catenaccio"? Noi giochiamo così..." [World Cup: Trapattoni, "Catenaccio"? We play that way...] (in Italian). ADNKronos. 2002-06-04. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Foot, John (2007-08-24). "Winning at All Costs: A Scandalous History of Italian Soccer". Nation Books. p. 481.

- ↑ Tosatti, Giorgio (2004-07-05). "La Grecia nel mito del calcio. Con il catenaccio" [Greece in the football legends. With Catenaccio] (in Italian). Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Williams, Richard (2006-06-27). "Totti steps up to redeem erratic Italy". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Previous World Cups: Germany 2006". FIFA.com. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- ↑ "Previous World Cups: Korea/Japan 2002". FIFA.com. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

References

- Giulianotti, Richard, Football: A Sociology of the Global Game. London: Polity Press 2000. ISBN 0-7456-1769-7

- Trapattoni, Giovanni, Coaching High Performance Soccer. Spring City, PA: Reedswain Inc. 2000. ISBN 1-890946-37-0

External links

| Look up catenaccio in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |