Cat communication

.jpg)

Cat communication is the transfer of information by one or more cats that has an effect on the current or future behaviour of another animal, including humans. Cats use a range of communication modalities including visual, auditory, tactile, chemical and gustatory.

The communication modalities used by domestic cats have been affected by domestication.[1]

Vocalizations

|

A cat meowing

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Cat vocalisations have been categorised according to a range of characteristics.

Schötz categorised vocalizations according to 3 mouth actions: (1) sounds produced with the mouth closed (murmurs), including the purr, the trill and the chirrup, (2) sounds produced with the mouth open and gradually closing, comprising a large variety of miaows with similar vowel patterns, and (3) sounds produced with the mouth held tensely open in the same position, often uttered in aggressive situations (growls, yowls, snarls, hisses, spits and shrieks).[2]

Brown et al. categorised vocal responses of cats according to the behavioural context: (1) during separation of kittens from mother cats, (2) during food deprivation, (3) during pain, (4) prior to or during threat or attack behavior, as in disputes over territory or food, (5) during a painful or acutely stressful experience, as in routine prophylactic injections and (6) during kitten deprivation.[3] Less commonly recorded calls from mature cats included purring, conspecific greeting calls or murmurs, extended vocal dialogues between cats in separate cages, “frustration” calls during training or extinction of conditioned responses.

Miller classified vocalisations into 5 categories according to the sound produced: the purr, chirr, call, meow and growl/snarl/hiss.[4]

Purr

The purr is a continuous, soft, vibrating sound made in the throat by most species of felines. Domestic cat kittens can purr as early as two days of age.[4] This tonal rumbling can characterize different personalities in domestic cats. Purring is often believed to indicate a positive emotional state, however, cats sometimes purr when they are ill, tense, or experiencing traumatic or painful moments.[5]

The mechanism of how cats purr is elusive. This is partly because cats do not have a unique anatomical feature that is clearly responsible for the vocalization.[6] One hypothesis, supported by electromyographic studies, is that cats produce the purring noise by using the vocal folds and/or the muscles of the larynx to alternately dilate and constrict the glottis rapidly, causing air vibrations during inhalation and exhalation.[7] Combined with the steady inhalation and exhalation as the cat breathes, a purring noise is produced with strong harmonics. Purring is sometimes accompanied by other sounds, though this varies between individuals. Some may only purr, while other cats include low level outbursts sometimes described as "lurps" or "yowps".

Domestic cats purr at varying frequencies. One study reported that domestic cats purr at average frequencies of 21.98 Hz in the egressive phase and 23.24 Hz in the ingressive phase with an overall mean of 22.6 Hz.[8] Further research on purring in four domestic cats found that the fundamental frequency varied between 20.94 and 27.21 Hz for the egressive phase and between 23.0 and 26.09 Hz for the ingressive phase. There was considerable variation between the four cats in the relative amplitude, duration and frequency between egressive and ingressive phases, although this variation generally occurred within the normal range.[9]

One study on a single cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) showed it purred with an average frequency of 20.87 Hz (egressive phases) and 18.32 Hz (ingressive phases).[8] A further study on four adult cheetahs found that mean frequencies were between 19.3 Hz and 20.5 Hz in ingressive phases, and between 21.9 Hz and 23.4 Hz in egressive phases. The egressive phases were longer than ingressive phases and moreover, the amplitude was greater in the egressive phases.[10]

It was once believed that only the cats of the genus Felis could purr.[11] However, felids of the genus Panthera (tigers, lions, jaguars and leopards) also produce sounds similar to purring, but only when exhaling. The subdivision of the Felidae into ‘purring cats’ on the one hand and ‘roaring cats ’ (i.e. non-purring) on the other, originally goes back to Owen (1834/1835) and was definitely introduced by Pocock (1916), based on a difference in hyoid anatomy. The ‘roaring cats’ (lion, Panthera leo; tiger, P. tigris; jaguar, P. onca; leopard, P. pardus) have an incompletely ossified hyoid, which according to this theory, enables them to roar but not to purr. On the other hand, the snow leopard (Uncia uncia), as the fifth felid species with an incompletely ossified hyoid, purrs (Hemmer, 1972). All remaining species of the family Felidae (‘purring cats’) have a completely ossified hyoid which enables them to purr but not to roar. However, Weissengruber et al. (2002) argued that the ability of a cat species to purr is not affected by the anatomy of its hyoid, i.e. whether it is fully ossified or has a ligamentous epihyoid, and that, based on a technical acoustic definition of roaring, the presence of this vocalization type depends on specific characteristics of the vocal folds and an elongated vocal tract, the latter rendered possible by an incompletely ossified hyoid.

Mew

Mew are one of the most widely known vocalizations of domestic kittens. It is a call apparently used to solicit attention from the mother.[4]

Adult cats commonly vocalise with a "meow" (or "miaow") sound, which is onomatopoeic. The mew can be assertive, plaintive, friendly, bold, welcoming, attention soliciting, demanding, or complaining. It can even be silent, where the cat opens its mouth but does not vocalize. Humans tend to find this silent mew particularly plaintive and appealing. Adult cats do not usually meow to each other and so meowing to human beings is likely to be an extension of the use by kittens.[12]

Language differences

Different languages have correspondingly different words for the "meow" sound, including miau (Belarusian, Croatian, Hungarian, Dutch, Finnish, Lithuanian, Malay, German, Polish, Russian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish and Ukrainian), mňau (Czech), meong (Indonesian), niau (Ukrainian), niaou (νιάου,[13] Greek), miaou (French), nya (ニャ, Japanese), miao (喵, Mandarin Chinese, Italian), miav/miao or mjav/mjau (Danish, Swedish and Norwegian), mjá (Icelandic), ya-ong (야옹, Korean), میاؤں / Miyāʾūṉ (Urdu)[14] and meo-meo (Vietnamese).[15] In some languages (such as Chinese 貓, māo), the vocalization became the name of the animal itself.

Chirr

The chirr or chirrup sounds like a meow rolled on the tongue. It is used most commonly by mother cats calling their kittens from the nest. It is also used by friendly cats when eliciting the approach of another cat or a human. Humans can mimic the sound to reassure and greet pet cats.[4]

Cats sometimes make chirping or chattering noises when observing or stalking prey.

Call

The call is loud, rhythmic sound made with the mouth closed. It is primarily associated with female cats soliciting males, and sometimes occurs in males when fighting with each other.[4] A "caterwaul" is the cry of a cat in estrus (or "in heat").[12][16]

Growl, snarl and hiss

The growl, snarl and hiss are all vocalisations associated with either offensive or defensive aggression. They are usually accompanied by a postural display intended to have a visual effect on the perceived threat. The communication may be directed at cats as well as other species – the puffed-up hissing and spitting display of a cat toward an approaching dog is a well-known behavior. Kittens as young as two to three weeks will hiss and spit when first picked up by a human.[4]

Ultrasonic

Very high frequency (“ultrasonic”) response components have been observed in kitten vocalizations.[3]

Visual

Cats use postures and movement to communicate a wide range of information. Some include a wide range of responses such as when cats arch their backs, erect their hairs and adopt a sideward posture to communicate fear or aggression. Others may be only a single behavioural change (as perceived by humans) such as slowly blinking to signal relaxation.

Domestic cats frequently use visual communication with their eyes, ears, mouths, tails, coats and body postures. It has been stated that a cat’s facial features change the most and are probably the best indicator of cat communication.[4]

Posture

A cat lying with its belly exposed communicates trust[citation needed] and comfort (this is also typical of overweight cats, as it is more comfortable for them); however, a cat may also roll on its side or back to defend itself with its claws.

Calm cats tend to stand relaxed with a still tail. If they become aggressive, the hind legs stiffen, the rump elevates but the back stays flat, tail hairs are erected, the nose is pushed forward and the ears pulled back slightly. This it to elicit deference by the competitor. The aggressor may attempt to make challengers retreat and will pursue them if they do not defer. A fearful, defensive cat makes itself smaller, lowers itself toward the ground, arches its back and leans its body away from the threat rather than forward. The cat tries to avoid combat, which could result in injury. Fighting usually occurs only when escape is impossible.[4]

Flattened ears generally indicate that a cat feels threatened and may attack. Having the mouth open and no teeth exposed indicates playfulness.[17]

Ears

Cats can change the position of their ears very quickly, in a continuum from erect when the cat is alert and focused, slightly relaxed when the cat is calm, and flattened against the head when extremely defensive or aggressive.

Eyes

Cats also communicate with their eyes. Sometimes, changes in the eyes can occur so quickly it is difficult for humans to discern. Round pupils are generally associated with fear, oblong pupils with aggression/excitement, and slightly off-round with a state of relaxation. A larger pupil generally indicates a more intense emotion. A direct stare is usually a challenge or threat, more likely to be seen in high-ranking cats. Lower-ranking cats usually withdraw in response.[4] However, when directed at a human, near-continuous eye contact accompanied by a relaxed/non-aggressive body posture usually communicates trust or possibly curiosity; usually the cat will blink or briefly look slightly aside periodically, to indicate that it is not challenging or stalking the human. Cats generally perceive a fixed stare from another cat or larger animal as a threat of attack, either for predation or for territorial motives, and when not confronting such a perceived threat, a cat will blink or look away periodically to avoid provoking the same defensive response that a solid stare would elicit from themselves.[citation needed]

Tail

Cats often use their tail to communicate. Cats holding the tail vertically generally indicates positive emotions such as happiness or confidence and is often used as a friendly greeting toward human beings or other cats (usually close relatives). A half-raised tail can indicate less pleasure, and unhappiness is indicated with a tail held low. In addition, a cat's tail may swing from side to side. If this motion is slow and "lazy", it generally indicates that the cat is in a relaxed state, and is thought to be a way for the cat to search and monitor the surroundings behind it. Cats will twitch the tips of their tails when hunting or when irritated, while larger twitching indicates displeasure. A stalking domestic cat will typically hold its tail low to the ground while in a crouch, and twitch it quickly from side to side. This tail behavior is also seen when a cat has become "irritated" and is nearing the point of biting or scratching. They may also twitch their tails when playing.[18] Sometimes during play, a cat, or more commonly, a kitten, will raise the base of their tail high and stiffen all but the tip into a shape like an upside-down "U". This signals great excitement, to the point of hyperactivity. This may also be seen when younger cats chase each other, or when they run around by themselves. When greeting their owner, cats often hold their tails straight up with a quivering motion that indicates extreme happiness.[19] A scared or surprised cat may erect the hairs on its tail and back. In addition, it may stand more upright and turn its body sideways to increase its apparent size as a threat. Tailless cats, such as the Manx, which possess only a small stub of a tail, move the stub around as if they possess a full tail.

Tactile

Cats often lick other cats and humans. Cats may lick for allogrooming purposes or to bond (this grooming is usually done between cats who are familiar). They will also sometimes lick humans for similar reasons. These reasons include wanting to "groom" people and to show them care and affection.

Cats may paw humans or soft objects with a kneading motion. Cats often purr during this behaviour, usually indicating contentment and affection. This can also indicate curiosity. A cat may also do this when in pain or dying, as a method of comforting itself. It is instinctive to cats, and they use it when they are young to stimulate the mother cat's breast to release milk during nursing.

Domestic cats communicate information about themselves by scratching and kneading substrates in localised areas. Cats have scent glands on the underside of their paws which release small amounts of scent onto the person or object being kneaded.

Touching noses, also known as "sniffing noses", is a friendly tactile greeting for cats.

Some cats rub their faces on humans as a friendly greeting or sign of affection. This visual action is also olfactory communication as it leaves a scent from the scent glands located in the cat's cheeks. Cats also perform a "head bonk" (or "bunt"), in which they bump a human or other cat with the front part of the head, which also contains scent glands.[20] Head-bumping may also be a display of social dominance, and cheek rubbing is often exhibited by a dominant cat towards a subordinate.[4]

Biting

Gentle biting in the absence of vocalisations can communicate playfulness; however, stronger bites that are accompanied by hissing or growling usually communicate aggression.[21] When cats mate, the tom bites the scruff of the female's neck as she assumes a lordosis position which communicates that she is receptive to mating.

Olfactory

Cats communicate olfactarily through scent in urine, feces, and chemicals or pheromones from glands located around the mouth, chin, forehead, cheeks, lower back, tail and paws.[22] Their rubbing and head-bumping behaviors are methods of depositing these scents on substrates, including humans.

Urine spraying is also a territorial marking.[23] Although cats may mark with both sprayed and non-sprayed urine, the spray is usually more thick and oily than normally deposited urine, and may contain additional secretions from anal sacs that help the sprayer to make a stronger communication. While cats mark their territory both by rubbing of the scent glands and by urine and fecal deposits, spraying, most frequently engaged in by unneutered male cats in competition with others of their same sex and species, seems to be the loudest feline olfactory statement. Female cats also sometimes spray.[4]

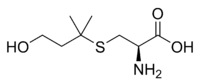

The urine of mature male cats in particular contains the amino acid known as felinine which is a precursor to 3-mercapto-3-methylbutan-1-ol (MMB), the sulfur-containing compound that gives cat urine its characteristically strong odor. Felinine is produced in the urine from 3-methylbutanol-cysteinylglycine (3-MBCG) by the excreted peptidase cauxin. It then slowly degrades via bacterial lyase into the more-volatile chemical MMB.[24] Felinine is a possible cat pheromone.

| → |

| Felinine | MMB |

See also

References

- ↑ Turner, D.C.; Bateson, P.P.G; Bateson, P. The Domestic Cat: The Biology Of Its Behaviour. Cambridge University Press. p. 68.

- ↑ Schötz, Susanne (May 30 – June 1, 2012). "A phonetic pilot study of vocalizations in three cats" (PDF). Proceedings Fonetik 2012. The XXVth Swedish Phonetics conference. University of Gothenburg. pp. 45–58.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Brown, K.A., Buchwald, J.S., Johnson, J.R. and Mikolich, D.J. (1978). "Vocalization in the cat and kitten". Developmental Psychobiology 11 (6): 559–570. doi:10.1002/dev.420110605.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 Miller, P. (2000). "Whisker whispers". Association of Animal Behavior Professionals. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Turner, D.C.; Bateson (eds.), P. (2000). The Domestic Cat: The Biology Of Its Behaviour. Cambridge University Press. pp. 71, 72, 86 and 88. ISBN 978-0521-63648-3. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "Why and how do cats purr?". Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ Dyce, K.M.; Sack, W.O.; Wensing, C.J.G. (2002). Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, 3rd ed. Saunders, Philadelphia. p. 156.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Eklund, R.; Peters, G.; Duthie, E.D. "An acoustic analysis of purring in the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and in the domestic cat (Felis catus)". Proceedings from Fonetik 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Schötz, S.; Eklund, R. "A comparative acoustic analysis of purring in four cats". Proceedings from Fonetik 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Eklund, R.; Peters, G.; Weise, F.; Munro, S. "A comparative acoustic analysis of purring in four cheetahs". Proceedings from Fonetik 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Breton, R. Roger; Creek, Nancy J. "Overview of Felidae". Cougar Hill Web. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Meowing and Yowling". Virtual Pet Behaviorist. ASPCA. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ "νιαουρίζω". Word Reference (in Greek). WordReference.com. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ فیروز الدین, مولوی. فیروز اللغات اردو جامع (in Urdu) (2nd ed.). Lahore: Feroz Sons, Ltd. p. 1334. ISBN 9690005146.

- ↑ Peggy Bivens (2002). Language Arts 1, Volume 1. Saddleback Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 978-1562-54508-6.

- ↑ "caterwaul". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Helgren, J. Anne (1999). Communicating with Your Cat. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0-7641-0855-7.

- ↑ Cat articles on Iams website

- ↑ "Common Cat Behaviors". Best Cat Tips. http://www.best-cat-tips.com. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Mary White. "Cat Behavior Tips". LifeTips. LifeTips. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ "Play Therapy Pt. 2," Cats International retrieved May 22, 2007

- ↑ "Communication - how do cats communicate?". vetwest animal hospitals. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Dennis C. Turner; Patrick Bateman, eds. (2000). The Domestic Cat (2nd ed.). University Press, Cambridge. pp. 69–70. ISBN 0521636485. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ M. Miyazaki, T. Yamashita, Y. Suzuki, Y. Saito, S. Soeta, H. Taira, and A. Suzuki (October 2006). "A major urinary protein of the domestic cat regulates the production of felinine, a putative pheromone precursor". Chem. Biol. (pdf) 13 (10): 1071–9. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.013. PMID 17052611.