Castle Pinckney

|

Castle Pinckney | |

| |

|

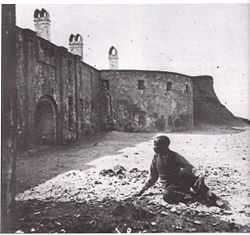

View of Castle Pinckney, 1861 | |

| |

| Nearest city | Charleston, South Carolina |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°46′25″N 79°54′41″W / 32.77361°N 79.91139°WCoordinates: 32°46′25″N 79°54′41″W / 32.77361°N 79.91139°W |

| Built | 1808 |

| Architect | Unknown |

| Architectural style | Other |

| Governing body | Private |

| NRHP Reference # | 70000574[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 16, 1970 |

Castle Pinckney was a small masonry fortification constructed by the United States government by 1810 in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina.[2][3] It was used very briefly as a prisoner-of-war camp (six weeks) and artillery position during the American Civil War. It was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.[1]

History

Located on Shutes' Folly, an island one mile offshore from Charleston, the Castle fort was built over the ruins of an older fortification called "Fort Pinckney". The original log and earthen fort, named after the Revolutionary War hero Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, was built beginning in 1797 and was intended to protect the city from a possible naval attack when war with France seemed imminent. Completed in 1804, it saw no hostilities and was virtually destroyed by a severe hurricane in September of that year. A replacement brick and mortar structure called "Castle Pinckney" was erected in 1809–1810 and was garrisoned throughout the War of 1812, but saw no action. Afterwards, Castle Pinckney was abandoned and fell into disrepair.[4]

Two decades later, a sea wall was completed and the fort was re-garrisoned during the Nullification Crisis of 1832, when President Andrew Jackson prepared to collect a controversial tariff using military force if necessary. After that brief period of activity, the fort again fell into disuse and was primarily a storehouse for gunpowder and other military supplies.

By the late 1850s, Castle Pinckney was part of a network of defensive positions in the harbor, which included the larger and more strategically placed Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie, and other smaller earthworks and fortifications. In 1860, Castle Pinckney's armament consisted of fourteen 24-pounders, four 42-pounders, four 8-inch howitzers, one 10-inch and one 8-inch mortar and four light fieldpieces to protect its flanks. On December 27, 1860, one week after South Carolina seceded from the Union, the fort was surrendered to South Carolina militia by its small garrison, which retired to Fort Sumter to join Major Robert Anderson. Castle Pinckney became the first Federal military position seized forcefully by a Southern state government. Three days later, the Charleston Arsenal joined Castle Pinckney in falling to the militia. After the subsequent attack on Fort Sumter, the Charleston Zouave Cadets manned Castle Pinckney.

One hundred and fifty-four Union Army prisoners of war (120 enlisted, 34 officers) captured during the First Battle of Manassas and previously incarcerated at Ligon's Prison arrived at Charleston on September 10, 1861 and were kept at the Charleston City Jail until the lower casements of Castle Pinckney were converted into cells. According to the Charleston Mercury, Richmond officials had selected "chiefly from among those who have evidenced the most insolent and insubordinate disposition." On September 18, prisoners from the 11th NY Fire Zouaves, 69th NY ("Irish") Regiment, 79th NY Regiment, and 8th Michigan Infantry were transferred to Castle Pinckney. They were allowed to wander during the day and were confined to cells only at night. The Castle quickly proved to be too small and inadequate however for permanent confinement and the prisoners were transferred back to the Charleston City Jail on October 31, 1861 after only six weeks. After the prisoners were removed, the fort was strengthened with earthen embankments and additional mortars and Columbiads on the barbette tier. On December 12, the prisoners were transferred back to the island following a fire which had burned a large section of Charleston and damaged the jail. They remained for just over a week with many sleeping on the inner parade ground before being transferred.[5]

After the Civil War, the fort was modernized for possible use during the Spanish-American War but again was not needed. Some sources suggest that the fort never fired a single hostile shot during its lengthy existence. Parts of the old brick walls and casemates were dismantled in 1890 to make way for a harbor lighthouse, which operated into the 20th century. There was local opposition to the plans for the lighthouse; a movement had been undertaken to construct a retirement home for servicemen on the island instead.[6] Castle Pinckney was declared a U.S. National Monument in 1924 by presidential proclamation. In 1951, Congress passed a bill to abolish Castle Pinckney National Monument and transferred it back to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.[7] The island became excess property subject to sale by the federal government in March 1956.[8] The island was acquired by the State Ports Commission as a spoil area in 1958 for $12,000, but the Commission investigated improving part of the land and using it as a historic destination.[9] Plans for the use of the island as a spoil area proved impractical, and no successful plans for the use of the island as a tourist destination were created by the Commission. The Commission attempted to return the island to the federal government, but the federal government declined, citing the cost of operations as outweighing the historical value of the island. The Commission fielded offers to buy the island for uses including a private residence, a nightclub, and a restaurant but refused all of them.[10] A fire on December 22, 1967, destroyed an abandoned house on the island, but a warehouse was saved.[11]

A local Sons of Confederate Veterans fraternal post took over management and care of the island in the late 1960s and attempted to preserve it and establish a museum.[12] Castle Pinckney was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.[1] Eventually, unable to raise the needed funds, the SCV allowed the fort to revert to state ownership. Castle Pinckney has recently undergone some limited restoration efforts. Due its location on an isolated shoal in the middle of the harbor, access is limited, if not nonexistent, and maintenance near impossible. It is gradually being reclaimed by nature.

In June, 2011, Castle Pinckney was sold to the Fort Sumter Camp No. 1269, Sons of Confederate Veterans for $10.[13]

See also

- List of Civil War POW Prisons and Camps

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2010-07-09.

- ↑ Fant, Mrs. James W. (May 16, 1970). "Castle Pinckney" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "Castle Pinckney, Charleston County (Shute’s Folly Island, Charleston Harbor)". National Register Properties in South Carolina. South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ Michael P. Higgins (1992-07-16). "History of Castle Pinckney". SC State Ports Authority.

- ↑ Lonnie R. Speer (2006). Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 25–30. ISBN 0-8032-9342-9.

- ↑ "Castle Pinckney Sanitarium". Charleston News & Courier. October 2, 1899. p. 8. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Castle Pinckney's National Monument Status Removed". Charleston News & Courier. August, 16, 1951. pp. 6A. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Government Says Castle Pinckney Excess Property". Charleston News & Courier. March 31, 1956. pp. 10A. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Work Is Under Way At Castle Pinckney". Charleston News & Courier. July 23, 1958. pp. B1. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Castle Pinckney Becoming Problem". Charleston News & Courier. July 21, 1964. pp. B1. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Mysterious Blaze Destroys House At Castle Pinckney". Charleston News & Courier. December 23, 1967. pp. 1A. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Castle Pinckney Becomes Memorial". Charleston News & Courier. April 13, 1969. pp. D1. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.wistv.com/Global/story.asp?S=14956695

External links

- Civil War Prisons

- The American Civil War; Prisoner of War Camps

- Castle Pinckney, at South Carolina Department of Archives and History

- Castle Pinckney restoration

- National Park Service overview of Castle Pinckney

| |||||||||||||||||