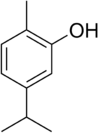

Carvacrol

| Carvacrol[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| IUPAC name 5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol [citation needed] | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 499-75-2 |

| PubChem | 10364 |

| ChemSpider | 21105867 |

| UNII | 9B1J4V995Q |

| KEGG | C09840 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL281202 |

| Jmol-3D images | Image 1 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C10H14O |

| Molar mass | 150.217 g/mol |

| Density | 0.9772 g/cm3 at 20 °C |

| Melting point | 1 °C; 34 °F; 274 K |

| Boiling point | 237.7 °C; 459.9 °F; 510.8 K |

| Solubility in water | insoluble |

| Solubility | soluble in ethanol, diethyl ether, carbon tetrachloride, acetone[2] |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| Infobox references | |

Carvacrol, or cymophenol, C6H3CH3(OH)(C3H7), is a monoterpenoid phenol. It has a characteristic pungent, warm odor of oregano.[3]

Natural occurrence

Carvacrol is present in the essential oil of Origanum vulgare (oregano), oil of thyme, oil obtained from pepperwort, and wild bergamot. The essential oil of Thyme subspecies contains between 5% and 75% of carvacrol, while Satureja (savory) subspecies have a content between 1% and 45%. Origanum majorana (marjoram) and Dittany of Crete are rich in carvacrol, 50% resp. 60-80%.[4]

It is also found in tequila.[5]

Biological properties and use

Carvacrol inhibits the growth of several bacteria strains, e.g. Escherichia coli[6] and Bacillus cereus. Its low toxicity together with its pleasant taste and smell suggests its use as a food additive to prevent bacterial contamination.[7] In Pseudomonas aeruginosa it causes damages to the cell membrane of these bacteria and, unlike other terpenes, inhibits the proliferation of this germ.[8] The cause of the antimicrobial properties is believed to be disruption of the bacteria membrane.[9][10]

It is a potent activator of the human ion channels transient receptor potential V3 (TRPV3) and A1 (TRPA1).[11] Application of carvacrol on the human tongue, as well as activation of TRPV3, causes a sensation of warmth. In addition carvacrol also activates, but rapidly desensitizes the pain receptor TRPA1 explaining its pungency.[11]

It activates PPAR and suppresses COX-2 inflammation.[12]

In rats, carvacrol is quickly metabolized and excreted. The main metabolic route is esterification of the phenolic group with sulfuric acid and glucuronic acid. A minor pathway is oxidation of the terminal methyl groups to primary alcohols. After 24 hours only very small amounts of carvacrol or its metabolites could be found in urine, indicating an almost complete excretion within one day.[13]

A study led by Supriya Bavadekar reports that carvacrol stimulates apoptosis in prostate cancer cells.[14]

Synthesis and derivatives

Carvacrol may be synthetically prepared by the fusion of cymol sulfonic acid with caustic potash; by the action of nitrous acid on 1-methyl-2-amino-4-propyl benzene; by prolonged heating of five parts of camphor with one part of iodine; or by heating carvol with glacial phosphoric acid or by performing a dehydrogenation of carvone with a Pd/C catalyst. It is extracted from Origanum oil by means of a 50% potash solution. It is a thick oil that sets at 20 °C to a mass of crystals of melting point 0 °C, and boiling point 236–237 °C. Oxidation with ferric chloride converts it into dicarvacrol, whilst phosphorus pentachloride transforms it into chlorcymol.

List of the plants that contain the chemical

- Monarda didyma[15]

- Nigella sativa[16]

- Origanum compactum[17]

- Origanum dictamnus[18]

- Origanum microphyllum[19]

- Origanum onites[20], [21]

- Origanum scabrum[19]

- Origanum vulgare[22][23]

- Thymus glandulosus[17]

Toxicology

Carvacrol does not have many long-term genotoxic risks. The cytotoxic effect of carvacrol can make it an effective antiseptic and antimicrobial agent. Carvacrol has been found to show antioxidant activity.[24]

Antimicrobial activity:

- 25 Different periodontopathic bacteria and strains[25]

- Cladosporium herbarum [25]

- Penicillium glabrum[25]

- Fungi such as F. moniliforme, R. solani, S. sclerotirum, and P. capisci[25]

Compendial status

See also

- Acceptable daily intake

- Thymol

- Essential Oils

Notes & references

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

- ↑ "Carvacrol data sheet from Sigma-Aldrich".

- ↑ Lide, David R. (1998). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87 ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 3–346. ISBN 0-8493-0594-2

- ↑ Ultee A, Slump RA, Steging G, Smid EJ (2000). "Antimicrobial activity of carvacrol toward Bacillus cereus on rice". J. Food Prot. 63 (5): 620–4. PMID 10826719.

- ↑ De Vincenzi M, Stammati A, De Vincenzi A, Silano M (2004). "Constituents of aromatic plants: carvacrol". Fitoterapia 75 (7–8): 801–4. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2004.05.002. PMID 15567271.

- ↑ Characterization of volatile compounds from ethnic Agave alcoholic beverages by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. León-Rodríguez, A. de, Escalante-Minakata, P., Jiménez-García, M. I., Ordoñez-Acevedo, L. G., Flores Flores, J. L. and Barba de la Rosa, A. P., Food Technology and Biotechnology, 2008, Volume 46, Number 4, pages 448-455 (abstract)

- ↑ Du WX, Olsen CE, Avena-Bustillos RJ, McHugh TH, Levin CE, Friedman M (2008). "Storage Stability and Antibacterial Activity against Escherichia coli O157:H7 of Carvacrol in Edible Apple Films Made by Two Different Casting Methods". J. Agric. Food Chem. 56 (9): 3082–8. doi:10.1021/jf703629s. PMID 18366181.

- ↑ Ultee A, Smid EJ (2001). "Influence of carvacrol on growth and toxin production by Bacillus cereus". Int. J. Food Microbiol. 64 (3): 373–8. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00480-3. PMID 11294360.

- ↑ Cox SD, Markham JL (2007). "Susceptibility and intrinsic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to selected plant volatile compounds". J. Appl. Microbiol. 103 (4): 930–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03353.x. PMID 17897196.

- ↑ Di Pasqua R, Betts G, Hoskins N, Edwards M, Ercolini D, Mauriello G (2007). "Membrane toxicity of antimicrobial compounds from essential oils". J. Agric. Food Chem. 55 (12): 4863–70. doi:10.1021/jf0636465. PMID 17497876.

- ↑ Cristani M, D'Arrigo M, Mandalari G, et al. (2007). "Interaction of four monoterpenes contained in essential oils with model membranes: implications for their antibacterial activity". J. Agric. Food Chem. 55 (15): 6300–8. doi:10.1021/jf070094x. PMID 17602646.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Xu H, Delling M, Jun JC, Clapham DE (2006). "Oregano, thyme and clove-derived flavors and skin sensitizers activate specific TRP channels". Nat. Neurosci. 9 (5): 628–35. doi:10.1038/nn1692. PMID 16617338.

- ↑ Hotta, M.; Nakata, R.; Katsukawa, M.; Hori, K.; Takahashi, S.; Inoue, H. (2010). "Carvacrol, a Component of Thyme Oil, Activates PPAR and Suppresses COX-2 Expression". Journal of Lipid Research, 51: 132–9. doi:10.1194/jlr.M900255-JLR200.

- ↑ Austgulen LT, Solheim E, Scheline RR (1987). "Metabolism in rats of p-cymene derivatives: carvacrol and thymol". Pharmacol. Toxicol. 61 (2): 98–102. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01783.x. PMID 2959918.

- ↑ http://www.liu.edu/Brooklyn/About/News/Press-Releases/2012/April/BK-PR-Apr25-2012.aspx

- ↑ http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/proceedings1993../V2-628.html

- ↑ http://www.herbapolonica.pl/magazines-files/2733672-art.3.pdf

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Bouchra, Chebli et al.; Achouri, Mohamed; Idrissi Hassani, L.M; Hmamouchi, Mohamed (2003). "Chemical composition and antifungal activity of essential oils of seven Moroccan Labiatae against Botrytis cinerea Pers: Fr". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 89 (1): 165–169. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00275-7. PMID 14522450.

- ↑ Liolios, C.C. et al.; Gortzi, O; Lalas, S; Tsaknis, J; Chinou, I (2009). "Liposomal incorporation of carvacrol and thymol isolated from the essential oil of Origanum dictamnus L. and in vitro antimicrobial activity". Food Chemistry 112 (1): 77–83. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.05.060.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Aligiannis, N. et al.; Kalpoutzakis, E.; Mitaku, Sofia; Chinou, Ioanna B. (2001). "Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oils of Two Origanum Species". J. Agric. Food Chem. 49 (9): 4168–4170. doi:10.1021/jf001494m. PMID 11559104.

- ↑ Coskun, Sevki et al.; Girisgin, O; Kürkcüoglu, M; Malyer, H; Girisgin, AO; Kirimer, N; Baser, KH (2008). "Acaricidal efficacy of Origanum onites L. essential oil against Rhipicephalus turanicus (Ixodidae)". Parasitology Research 103 (2): 259–261. doi:10.1007/s00436-008-0956-x. PMID 18438729.

- ↑ Ruberto, Giuseppe et al.; Biondi, Daniela; Meli, Rosa; Piattelli, Mario (2006). "Volatile flavour components of Sicilian Origanum onites L". Flavour and Fragrance Journal 8 (4): 197–200. doi:10.1002/ffj.2730080406.

- ↑ Kanias, G. D. et al.; Souleles, C.; Loukis, A.; Philotheou-Panou, E. (1998). "Trace elements and essential oil composition in chemotypes of the aromatic plant Origanum vulgare". Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 227 (1 – 2): 23–31. doi:10.1007/BF02386426.

- ↑ Figiel, Adam et al.; Szumny, Antoni; Gutiérrez-Ortíz, Antonio; Carbonell-Barrachina, ÁNgel A. (2010). "Composition of oregano essential oil (Origanum vulgare) as affected by drying method". Journal of Food Engineering 98 (2): 240–247. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.01.002.

- ↑ Özkan, Aysun; Erdoğan, Ayşe (2010). "A comparative evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of essential oil from Origanum onites (Lamiaceae) and its two major phenolic components". Tübitak 35 (2011): 735–742. doi:10.3906/biy-1011-170.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 American College of Toxicology (2006). "Final Report on the Safety Assessment of Sodium p-Chloro-m-Cresol, p-Chloro-m-Cresol, Chlorothymol, Mixed Cresols, m-Cresol, o-Cresol, p-Cresol, Isopropyl Cresols, Thymol, o-Cymen-5-ol, and Carvacrol". International Journal of Toxicology 25: 29–127. doi:10.1080/10915810600716653. PMID 16835130.

- ↑ The British Pharmacopoeia Secretariat (2009). "Index, BP 2009". Retrieved 29 March 2010.