Carthusians

| Carthusian Order | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | O.Cart., Carthusians |

| Motto | Stat crux dum volvitur orbis |

| Formation | 15 August 1084 |

| Type | Roman Catholic religious order |

| Headquarters | Grande Chartreuse (Mother House) |

| Key people | Bruno of Cologne, founder |

| Website |

www.chartreux.org www.vocatiochartreux.org |

The Carthusian Order, also called the Order of Saint Bruno, is a Roman Catholic religious order of enclosed monastics. The order was founded by Saint Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has its own Rule, called the Statutes, rather than the Rule of Saint Benedict, and combines eremitical and cenobitic life.

The name Carthusian is derived from the Chartreuse Mountains; Saint Bruno built his first hermitage in the valley of these mountains in the French Alps. The word charterhouse, which is the English name for a Carthusian monastery, is derived from the same source.[1] The same mountain range lends its name to the alcoholic cordial Chartreuse produced by the monks since the 1740s which itself gives rise to the name of the colour. The motto of the Carthusians is Stat crux dum volvitur orbis, Latin for "The Cross is steady while the world is turning."

Character

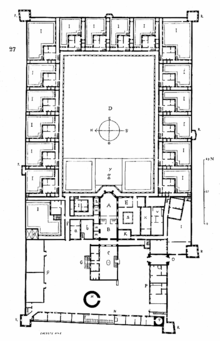

There are no Carthusian abbeys as they have no abbots, and each charterhouse is headed by a prior and is populated by choir monks, referred to as hermits, and lay brothers.

Each hermit — that is, a monk who is or who will be a priest — has his own living space, called a cell, usually consisting of a small dwelling. Traditionally there is a one-room lower floor for the storage of wood for a stove, a workshop as all monks engage in some manual labour. A second floor consists of a small entryway with an image of the Virgin Mary as a place of prayer, and a larger room containing a bed, a table for eating meals, a desk for study, a choir stall and kneeler for prayer. Each cell has a high walled garden, wherein the monk may meditate as well as grow flowers for himself and/or vegetables for the common good of the community, as a form of physical exercise.

The individual cells are organised so that the door of each cell comes off a large corridor. Next to the door is a small revolving compartment — called a "turn" — so that meals and other items may be passed in and out of the cell without the hermit having to meet the bearer. Most meals are provided in this manner, which the hermit then eats in the solitude of his cell. There are two meals provided for much of the year: lunch and supper. During seasons or days of fasting, just one meal is provided. The hermit makes his needs known to the lay brother by means of a note, requesting items such as a fresh loaf of bread, which will be kept in the cell for eating with several meals.

The hermit spends most of his day in the cell: he meditates, prays the minor hours of the Liturgy of the Hours on his own, eats, studies and writes (Carthusian monks have published scholarly and spiritual works), and works in his garden or at some manual trade. Unless required by other duties, the Carthusian hermit leaves his cell daily only for three prayer services in the monastery chapel, including the community Mass, and occasionally for conferences with his superior. Additionally, once a week, the community members take a long walk in the countryside during which they may speak; on Sundays and feastdays a community meal is taken in silence. Twice a year there is a day-long community recreation, and the monk may receive an annual visit from immediate family members.

The Carthusians do not engage in work of a pastoral or missionary nature. Unlike most monasteries, they do not have retreatants and those who visit for a prolonged period are people who are contemplating entering the monastery. As far as possible, the monks have no contact with the outside world. Their contribution to the world is their life of prayer, which they undertake on behalf of the whole Church and the human race.

In addition to the choir monks there are lay brothers, monks under slightly different types of vows who spend less time in prayer and more time in manual labour; they live a slightly more communal life, sharing a common area of the charterhouse. The lay brothers provide material assistance to the choir monks: cooking meals, doing laundry, undertaking physical repairs, providing the choir monks with books from the library and managing supplies. All of the monks live lives of silence.

Carthusian nuns live a life similar to the monks, but with some differences. Choir nuns tend to lead somewhat less eremitical lives, while still maintaining a strong commitment to solitude and silence.

Today, Carthusians live very much as they originally did, without any relaxing of their rules.

Carthusians in Britain

The first Carthusian monastery or 'Charterhouse' in England was founded by Henry II in Witham Friary, Somerset as penance for the murder of St Thomas Becket.

The best preserved remains of a medieval Charterhouse in the UK are at Mount Grace Priory near Osmotherley, North Yorkshire. One of the cells has been reconstructed to illustrate how different the lay-out is to monasteries of most other Christian orders, which are normally designed with communal living in mind.

The third Charterhouse built in Britain was Beauvale Charterhouse remains of which can still be seen in Beauvale, Greasley parish, Nottinghamshire.

The London Charterhouse gave its name to a square and several streets in the City of London, as well as to the Charterhouse School which used part of its site before moving out to Godalming, Surrey.

A few fragments remain of the Charterhouse in Coventry, mostly dating from the 15th century, and consisting of a sandstone building that was probably the prior's house. The area, about a mile from the centre of the city, is a conservation area, but the buildings are in use as part of a local college. Inside the building is a medieval wall painting, alongside many carvings and wooden beams. Nearby is the river Sherbourne that runs underneath the centre of the city.

A single Carthusian Priory was founded in Scotland during the Middle Ages, at Perth. It stood just west of the medieval town and was founded by James I (1406–1437) in the early 15th century. James I and his queen Joan Beaufort (died 1445) were both buried in the priory church, as was Queen Margaret Tudor (died 1541), widow of James IV of Scotland. The Priory, said to have been a building of 'wondrous cost and greatness' was sacked during the Scottish Protestant Revolution in 1559, and swiftly fell into decay. No remains survive above ground, though a Victorian monument marks the site. The Perth names Charterhouse Lane and Pomarium Flats (built on the site of the Priory's orchard) recall its existence.

St. Hugh's Charterhouse, Parkminster, West Sussex has cells running around a square cloister approximately 400 m (one quarter-mile) on a side, making it the largest cloister in Europe.[2]

Modern Carthusians

The Carthusians were greatly affected during the Protestant Reformation[citation needed] and during the French Revolution and after in France.[citation needed] Many of their monasteries were closed during both periods.

Today, the monastery of the Grande Chartreuse is still the Motherhouse of the Order. There is a museum illustrating the history of Carthusian order next to Grande Chartreuse; the monks of that monastery are also involved in producing Chartreuse liqueur. Visits are not possible within the Grande Chartreuse, but the 2005 documentary Into Great Silence gave unprecedented views of life within the hermitage. In the 21st century, the Sélignac Charterhouse was converted into a house in which lay people could come and experience Carthusian retreats, living the Carthusian life for shorter periods (an eight-day retreat being fixed as the absolute minimum, in order to enter at least somewhat into the silent rhythm of the charterhouse).

The only Carthusian monastery in the United States is the Charterhouse of the Transfiguration, on Mount Equinox near Arlington, Vermont. It was founded in the 1950s.

Liturgy

Before the Council of Trent in the 16th century, the Catholic Church in Western Europe had a wide variety of rituals for the celebration of Mass. Although the essentials were the same, there were variations in prayers and practices from region to region or among the various religious orders.

When Pope Pius V made the Roman Missal mandatory for all Catholics of the Latin Rite, he permitted the continuance of other forms of celebrating Mass that had an antiquity of at least two centuries. The rite used by the Carthusians was one of these, and still continues in use in a version revised in 1981.[3] Apart from the new elements in this revision, it is substantially the rite of Grenoble in the 12th century, with some admixture from other sources.[4] According to current Catholic legislation, however, priests can celebrate the traditional rites of their order without further authorization.

A feature unique to Carthusian liturgical practice is that the bishop bestows on Carthusian nuns, in the ceremony of their profession, a stole and a maniple. This is interpreted by some as a relic of the former rite of ordination of deaconesses.[5] The nun is also invested with a crown and a ring. The nun wears these ornaments again only on the day of her monastic jubilee, and after her death on her bier. At Matins, if no priest is present, a nun assumes the stole and reads the Gospel, and although the chanting of the Epistle was, in the time of the Tridentine Mass, reserved to an ordained subdeacon, a consecrated nun sang the Epistle at the conventual Mass, though without wearing the maniple. For centuries Carthusian nuns retained this rite, administered by the diocesan bishop four years after the nun took her vows.[6] It is no longer unique, since the liturgical reforms that followed Second Vatican Council made the rite of the consecration of virgins more widely available.

Stages of the Carthusian's life

- Postulancy (3 to 12 months) the postulant lives the life of a monk but without having professed any kind of vows.

- Novitiate (2 years). The novice wears a black cloak over the white Carthusian habit.

- Simple Vows (3 years) becomes a junior professed monk and wears the full Carthusian habit.

- Renewal of simple vows (2 years)

- Solemn profession.

Locations of monasteries

There are 25 active Charterhouses around the world, five of which are for nuns; altogether, there are around 370 monks and 75 nuns. They can be found in Argentina (1), Brazil (1), France (6), Germany (1), Italy (4), Portugal (1), Slovenia (1), South Korea (2), Spain (5), Switzerland (1), the United Kingdom (1) and the USA (1). The two in South Korea, one of monks and one of nuns, are of recent construction.[7]

See also

- "Into Great Silence"—an award winning documentary on the Carthusian monks

- List of Carthusian monasteries

- Monastic Family of Bethlehem, of the Assumption of the Virgin and of Saint Bruno

References

Notes

- ↑ In other languages: Dutch: Kartuize; French: Chartreuse; German: Kartause; Italian: Certosa; Polish: Kartuzja; Spanish: Cartuja

- ↑ The Monastery, BBC, broadcast May 2005, about 20 minutes into third episode.

- ↑ The text of the Carthusian Missal and the Order's other liturgical books is available at Carthusian Monks and Carthusian nuns

- ↑ "The Carthusian Order". in Catholic Encyclopedia. The text of the former Ordo Missae of the Carthusian Missal is available at "Cartusia Ordo Missae".

- ↑ "Deaconesses". in Catholic Encyclopedia; Alexander, David L. "A Rose By Any Other Name. The Ordination of Women to the Diaconate".

- ↑ "The Carthusian Order". in Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ To view complete list and images of the Monasteries visit: "The charterhouses in the world". Retrieved 15 October 2010.

Further reading

- Lockhart, Robin Bruce. Halfway to Heaven. London:Cistercian Publications, 1999 (Paperback,ISBN 0-87907-786-7)

- The Wound of Love, A Carthusian miscellany by priors and novice masters on various topics relating to the monastic ideal as lived in a charterhouse in our day. Gracewing Publishing, 2006, 256 p. (paperback, ISBN 0-85244-670-5)

- André Ravier, Saint Bruno the Carthusian. Online on the website of the Charterhouse of the Transfiguration

- Klein Maguire, Nancy. An Infinity of Little Hours: Five Young Men and Their Trial of Faith in the Western World's Most Austere Monastic Order. PublicAffairs, 2006 (Hardcover,ISBN 1-58648-327-7)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carthusians. |

- Official website of the Carthusian Order

- Official website of Carthusian vocations

- International Fellowship of St. Bruno

- Quies

- Article from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Cartusiana - History of the Carthusians in the Low Countries

- Official website Foundation The Carthusians of Roermond

- Writings by a former Carthusian monk

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||