Ancient Carthage

| Carthage | |||||

| |||||

Carthage and its dependencies in 264 BC | |||||

| Capital | Carthage | ||||

| Languages | Punic, Phoenician, Berber | ||||

| Religion | Punic religion | ||||

| Government | Monarchy until 308 BC, Republic thereafter | ||||

| King, later Shophet ("Judge") | See List of Monarchs of Carthage | ||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||

| - | Established | 650 BC | |||

| - | Disestablished | 146 BC | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

Ancient Carthage (from Phoenician 𐤒𐤓𐤕 𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕 Qart-ḥadašt[1]) was a Semitic civilization[2] centered on the Phoenician city-state of Carthage, located in North Africa on the Gulf of Tunis, outside what is now Tunis, Tunisia. It was founded in 814 BC.[3][4] Originally a dependency of the Phoenician state of Tyre, Carthage gained independence around 650 BC and established a hegemony over other Phoenician settlements throughout the Mediterranean, North Africa and what is now Spain[5] which lasted until the end of the 3rd century BC. At the height of the city's prominence, it was a major hub of trade with political influence extending over most of the western Mediterranean.

For much of its history, Carthage was in a constant state of struggle with the Greeks on Sicily and the Roman Republic, which led to a series of armed conflicts known as the Greek-Punic Wars and Punic Wars. The city also had to deal with the potentially hostile Berbers,[6] the indigenous inhabitants of the entire area where Carthage was built. In 146 BC, after the third and final Punic War, Carthage was destroyed and then occupied by Roman forces.[7] Nearly all of the other Phoenician city-states and former Carthaginian dependencies fell into Roman hands from then on.

History

Extent of Phoenician settlement

The Phoenicians established numerous colonial cities along the coasts of the Mediterranean[8] in order to provide safe harbors for their merchant fleets,[9] to maintain a Phoenician monopoly on an area's natural resources, and to conduct trade free of outside interference.[10] They were also motivated to found these cities to satisfy the demand for trade goods or to escape the necessity of paying tribute[11] to the succession of empires that ruled Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, and by fear of complete Greek colonization of that part of the Mediterranean suitable for commerce.[12] The Phoenicians lacked the population or necessity to establish large self-sustaining cities abroad, and most of their colonial cities had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, but Carthage and a few others developed larger populations.[13]

Carthaginian Control

Although Strabo's claim that the Tyrians founded three hundred colonies along the west African coast is clearly exaggerated, colonies were established in Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Iberia,[14] and to a much lesser extent, on the arid coast of Libya. The Phoenicians were active in Cyprus, Sardinia, Corsica, the Balearic Islands, Crete and Sicily, as well as on the European mainland at present-day Genoa in Italy and Marseille in present-day France.[15] The settlements at Crete and Sicily were in perpetual conflict with the Greeks,[16] but the Phoenicians managed to control all of Sicily for a limited time. The entire area later came under the leadership and protection of Carthage,[17] which in turn dispatched its own colonists to found new cities[18] or to reinforce those that declined with the loss of primacy of Tyre and Sidon.

The first colonies were settled on the two paths to Iberia's mineral wealth — along the North African coast and on Sicily, Sardinia and the Balearic Islands.[19] The centre of the Phoenician world was Tyre,[20] which served as its economic and political hub. The power of this city waned following numerous sieges by Babylonia,[21][22] and then its later voluntary submission to the Persian king Cambyses and incorporation within the Persian empire.[23] Supremacy passed to Sidon, and then to Carthage,[24] before Tyre's eventual destruction by Alexander the Great in 332 BC.[25] Each colony paid tribute to either Tyre or Sidon, but neither had actual control of the colonies. This changed with the rise of Carthage, since the Carthaginians appointed their own magistrates to rule the towns and Carthage retained much direct control over the colonies.[26] This policy resulted in a number of Iberian towns siding with the Romans during the Punic Wars.

Treaty with Rome

In 509 BC, a treaty was signed between Carthage and Rome[27] indicating a division of influence and commercial activities.[28] This is the first known source indicating that Carthage had gained control over Sicily and Sardinia.

5th century

By the beginning of the 5th century BC, Carthage had become the commercial center of the West Mediterranean region,[29] a position it retained until overthrown by the Roman Republic. The city had conquered most of the old Phoenician colonies (including Hadrumetum, Utica, and Kerkouane), subjugated the Libyan tribes (with the Numidian and Mauretanian kingdoms remaining more or less independent), and taken control of the entire North African coast from modern Morocco to the borders of Egypt (not including the Cyrenaica, which was eventually incorporated into Hellenistic Egypt).[30] Its influence had also extended into the Mediterranean, taking control over Sardinia, Malta, the Balearic Islands, and the western half of Sicily,[31] where coastal fortresses such as Motya or Lilybaeum secured its possessions. Important colonies had also been established on the Iberian Peninsula.[32] Their cultural influence in the Iberian Peninsula is documented,[33] but the degree of their political influence before the conquest by Hamilcar Barca is disputed.[34]

The Sicilian Wars

First Sicilian war

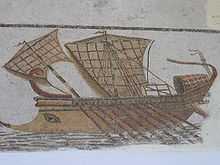

Carthage's economic successes, and its dependence on shipping to conduct most of its trade, led to the creation of a powerful Carthaginian navy.[35] This, coupled with its success and growing hegemony, brought Carthage into increasing conflict with the Greeks of Syracuse, the other major power contending for control of the central Mediterranean.[36]

The island of Sicily, lying at Carthage's doorstep, became the arena on which this conflict played out. From their earliest days, both the Greeks and Phoenicians had been attracted to the large island, establishing a large number of colonies and trading posts along its coast;[37] battles had been fought between these settlements for centuries.

By 480 BC, Gelo, the tyrant leader of Greek Syracuse, backed in part by support from other Greek city-states, was attempting to unite the island under his rule.[38] This imminent threat could not be ignored, and Carthage — possibly as part of an alliance with Persia, then engaged military force under the leadership of the general Hamilcar. Traditional accounts, including those of Herodotus and Diodorus, give Hamilcar's army a strength of three hundred thousand men; though these are certainly exaggerated, it must nonetheless have been of formidable strength.[39]

En route to Sicily, however, Hamilcar suffered losses (possibly severe) due to poor weather. Landing at Panormus (modern-day Palermo),[40] Hamilcar spent 3 days reorganizing his forces and repairing his battered fleet. The Carthaginians marched along the coast to Himera, and made camp before engaging in the Battle of Himera.[41] Hamilcar was either killed during the battle or committed suicide in shame.[42] As a result the nobility negotiated peace and replaced the old monarchy with a republic.[43]

Second Sicilian War

By 410 BC, Carthage had recovered after serious defeats. It had conquered much of modern day Tunisia, strengthened and founded new colonies in North Africa; Hanno the Navigator had made his journey down the African coast,[44][45] and Himilco the Navigator had explored the European Atlantic coast.[46] Expeditions were also led into Morocco and Senegal, as well as into the Atlantic.[47] In the same year, the Iberian colonies seceded, cutting off Carthage's major supply of silver and copper, while Hannibal Mago, the grandson of Hamilcar, began preparations to reclaim Sicily.

In 409 BC,[48] Hannibal Mago set out for Sicily with his force. He captured the smaller cities of Selinus (modern Selinunte) and Himera before returning triumphantly to Carthage with the spoils of war. But the primary enemy, Syracuse, remained untouched and, in 405 BC, Hannibal Mago led a second Carthaginian expedition to claim the entire island. This time, however, he met with fierce resistance and ill-fortune. During the siege of Agrigentum, the Carthaginian forces were ravaged by plague, Hannibal Mago himself succumbing to it.[49] Although his successor, Himilco, successfully extended the campaign by breaking a Greek siege, capturing the city of Gela and repeatedly defeating the army of Dionysius, the new tyrant of Syracuse, he, too, was weakened by the plague and forced to sue for peace before returning to Carthage.

In 398 BC, Dionysius had regained his strength and broke the peace treaty, striking at the Carthaginian stronghold of Motya. Himilco responded decisively, leading an expedition which not only reclaimed Motya, but also captured Messina.[50] Finally, he laid siege to Syracuse itself. The siege was close to a success throughout 397 BC, but in 396 BC plague again ravaged the Carthaginian forces,[51] and they collapsed.

The fighting in Sicily swung in favor of Carthage in 387 BC. After winning a naval battle off the coast of Catania, Himilco laid siege to Syracuse with 50,000 Carthaginians, but yet another epidemic struck down thousands of them. Dionysius then launched a counterattack by land and sea, and the Syracusans surprised the enemy fleet while most of the crews were ashore, destroying all the Carthaginian ships. At the same time, Dionysius' ground forces stormed the besiegers' lines and routed the Carthaginians. Himilco and his chief officers abandoned their army and fled Sicily.[52] Himilco returned to Carthage in disgrace and was very badly received; he eventually committed suicide[53] by starving himself.

Sicily by this time had become an obsession for Carthage. Over the next fifty years, Carthaginian and Greek forces engaged in a constant series of skirmishes. By 340 BC, Carthage had been pushed entirely into the southwest corner of the island, and an uneasy peace reigned over the island.

Third Sicilian War

In 315 BC, Agathocles, the tyrant (administrating governor) of Syracuse, seized the city of Messene (present-day Messina). In 311 BC he invaded the last Carthaginian holdings on Sicily, breaking the terms of the current peace treaty,[12] and laid siege to Akragas.

Hamilcar, grandson of Hanno the Navigator, led the Carthaginian response and met with tremendous success. By 310 BC, he controlled almost all of Sicily and had laid siege to Syracuse itself. In desperation, Agathocles secretly led an expedition of 14,000 men to the mainland,[54] hoping to save his rule by leading a counterstrike against Carthage itself. In this, he was successful: Carthage was forced to recall Hamilcar and most of his army from Sicily to face the new and unexpected threat. Although Agathocles' army was eventually defeated in 307 BC, Agathocles himself escaped back to Sicily and was able to negotiate a peace which maintained Syracuse as a stronghold of Greek power in Sicily.

Pyrrhic War

Between 280 and 275 BC, Pyrrhus of Epirus waged two major campaigns in the western Mediterranean: one against the emerging power of the Roman Republic in southern Italy, the other against Carthage in Sicily.[55]

Pyrrhus sent an advance guard to Tarentium under the command of Cineaus with 3,000 infantry. Pyrrhus marched the main army across the Greek peninsula and engaged in battles with the Thessalians and the Athenian army. After his early success on the march Pyrrhus entered Tarentium to rejoin with his advance guard.

In the midst of Pyrrhus's Italian campaigns, he received envoys from the Sicilian cities of Agrigentum, Syracuse, and Leontini, asking for military aid to remove the Carthaginian dominance over that island.[56][57] Pyrrhus agreed, and fortified the Sicilian cities with an army of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry[58] and 20 war elephants,[59] supported by some 200 ships. Initially, Pyrrhus' Sicilian campaign against Carthage was a success, pushing back the Carthaginian forces, and capturing the city-fortress of Eryx, even though he was not able to capture Lilybaeum.[60]

Following these losses, Carthage sued for peace, but Pyrrhus refused unless Carthage was willing to renounce its claims on Sicily entirely. According to Plutarch, Pyrrhus set his sights on conquering Carthage itself, and to this end, began outfitting an expedition. However, his ruthless treatment of the Sicilian cities in his preparations for this expedition, and his execution of two Sicilian rulers whom he claimed were plotting against him led to such a rise in animosity towards the Greeks, that Pyrrhus withdrew from Sicily and returned to deal with events occurring in southern Italy.[61][62]

Pyrrhus's campaigns in Italy were inconclusive, and Pyrrhus eventually withdrew to Epirus. For Carthage, this meant a return to the status quo. For Rome, however, the failure of Pyrrhus to defend the colonies of Magna Graecia meant that Rome absorbed them into its "sphere of influence", bringing it closer to complete domination of the Italian peninsula. Rome's domination of Italy, and proof that Rome could pit its military strength successfully against major international powers, would pave the way to the future Rome-Carthage conflicts of the Punic Wars.

The Punic Wars

When Agathocles died in 288 BC, a large company of Italian mercenaries who had previously been held in his service found themselves suddenly without employment. Rather than leave Sicily, they seized the city of Messana. Naming themselves Mamertines (or "sons of Mars"), they became a law unto themselves, terrorizing the surrounding countryside.[63]

The Mamertines became a growing threat to Carthage and Syracuse alike. In 265 BC, Hiero II, former general of Pyrrhus and the new tyrant of Syracuse, took action against them.[64] Faced with a vastly superior force, the Mamertines divided into two factions, one advocating surrender to Carthage, the other preferring to seek aid from Rome. While the Roman Senate debated the best course of action, the Carthaginians eagerly agreed to send a garrison to Messana. A Carthaginian garrison was admitted to the city, and a Carthaginian fleet sailed into the Messanan harbor. However, soon afterwards they began negotiating with Hiero; alarmed, the Mamertines sent another embassy to Rome asking them to expel the Carthaginians.

Hiero's intervention had placed Carthage's military forces directly across the narrow channel of water that separated Sicily from Italy. Moreover, the presence of the Carthaginian fleet gave them effective control over this channel, the Strait of Messina, and demonstrated a clear and present danger to nearby Rome and her interests.

As a result, the Roman Assembly, although reluctant to ally with a band of mercenaries, sent an expeditionary force to return control of Messana to the Mamertines.

The Roman attack on the Carthaginian forces at Messana triggered the first of the Punic Wars.[65] Over the course of the next century, these three major conflicts between Rome and Carthage would determine the course of Western civilization. The wars included a Carthaginian invasion led by Hannibal Barca, which nearly prevented the rise of the Roman Empire.

In 256-255 BC the Romans, under the command of Marcus Atilius Regulus, landed in Africa and after suffering some initial defeats the Carthaginian forces eventually repelled the Roman invasion.[64]

Shortly after the First Punic War, Carthage faced a major mercenary revolt which changed the internal political landscape of Carthage (bringing the Barcid family to prominence),[66] and affected Carthage's international standing, as Rome used the events of the war to base a claim by which it seized Sardinia and Corsica.

The Second Punic War lasted from 218 to 202 BC and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean, with the participation of the Berbers on Carthage's side.[67] The war is marked by Hannibal's surprising overland journey[68] and his costly crossing of the Alps, followed by his reinforcement by Gaulish allies and crushing victories over Roman armies in the battle of the Trebia and the giant ambush at Trasimene. Against his skill on the battlefield the Romans deployed the Fabian strategy. But because of the increasing unpopularity of this approach, the Romans resorted to a further major field battle.[67] The result was the crushing Roman defeat at Cannae.[69]

In consequence many Roman allies went over to Carthage, prolonging the war in Italy for over a decade, during which more Roman armies were destroyed on the battlefield. Despite these setbacks, the Roman forces were more capable in siegecraft[50] than the Carthaginians and recaptured all the major cities that had joined the enemy, as well as defeating a Carthaginian attempt to reinforce Hannibal at the battle of the Metaurus. In the meantime in Iberia, which served as the main source of manpower for the Carthaginian army, a second Roman expedition under Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major took New Carthage by assault[70] and ended Carthaginian rule over Iberia in the battle of Ilipa.[71] The final showdown was the battle of Zama in Africa between Scipio Africanus and Hannibal, resulting in the latter's defeat and the imposition of harsh peace conditions on Carthage, which ceased to be a major power and became a Roman client-state.[72]

The Third Punic War (149 BC to 146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars. The war was a much smaller engagement than the two previous Punic Wars and primarily consisted of a single main action, the Battle of Carthage, but resulted in the complete destruction of the city of Carthage,[73] the annexation of all remaining Carthaginian territory by Rome,[74] and the death or enslavement of thousands of Carthaginians.[75][76] The Third Punic War ended Carthage's independent existence.[77]

Culture

Language

Carthaginians spoke Punic, a variety of Phoenician,[78] which was a Semitic language originating in the Carthaginians' original homeland of Phoenicia (modern Lebanon).[79]

Economy

Carthaginian commerce extended by sea throughout the Mediterranean and perhaps into the Atlantic as far as the Canary Islands, and by land across the Sahara desert. According to Aristotle, the Carthaginians and others had treaties of commerce to regulate their exports and imports.[80][81]

The empire of Carthage depended heavily on its trade with Tartessos[82] and with other cities of the Iberian peninsula,[34] from which it obtained vast quantities of silver, lead, copper and – even more importantly – tin ore,[83] which was essential for the manufacture of bronze objects by the civilizations of antiquity. Carthaginian trade-relations with the Iberians, and the naval might that enforced Carthage's monopoly on this trade and that with tin-rich Britain,[84] made it the sole significant broker of tin and maker of bronze in its day. Maintaining this monopoly was one of the major sources of power and prosperity for Carthage; Carthaginian merchants strove to keep the location of the tin mines secret.[85] In addition to its role as the sole significant distributor of tin, Carthage's central location in the Mediterranean and control of the waters between Sicily and Tunisia allowed it to control the eastern peoples' supply of tin. Carthage was also the Mediterranean's largest producer of silver, mined in Iberia[86] and on the North African coast; after the tin monopoly, this was one of its most profitable trades. One mine in Iberia provided Hannibal with 300 Roman pounds (3.75 talents) of silver a day.[87][88]

Carthage's economy began as an extension of that of its parent city, Tyre.[89] Its massive merchant fleet traversed the trade routes mapped out by Tyre, and Carthage inherited from Tyre the trade in the extremely valuable dye Tyrian purple.[90] No evidence of purple dye manufacture has been found at Carthage, but mounds of shells of the murex marine snails from which it derived have been found in excavations of the Punic town which archaeologists call Kerkouane, at Dar Essafi on Cap Bon.[91] Similar mounds of murex have also been found at Djerba[92] on the Gulf of Gabes[73] in Tunisia. Strabo mentions the purple dye-works of Djerba[93] as well as those of the ancient city of Zouchis.[94][95][96] The purple dye became one of the most highly valued commodities in the ancient Mediterranean,[97] being worth fifteen to twenty times its weight in gold. In Roman society, where adult males wore the toga as a national garment, the use of the toga praetexta, decorated with a stripe of Tyrian purple about two to three inches in width along its border, was reserved for magistrates and high priests. Broad purple stripes (latus clavus) were reserved for the togas of the senatorial class, while the equestrian class had the right to wear narrow stripes (angustus clavus).[98][99]

Carthage produced finely embroidered silks,[100] dyed textiles of cotton, linen,[101] and wool, artistic and functional pottery, faience, incense, and perfumes.[102] Its artisans worked expertly with ivory,[103] glassware, and wood,[104] as well as with alabaster, bronze, brass, lead, gold, silver, and precious stones to create a wide array of goods, including mirrors, furniture[105] and cabinetry, beds, bedding, and pillows,[106] jewelry, arms, implements, and household items.[107] It traded in salted Atlantic fish and fish sauce (garum),[72] and brokered the manufactured, agricultural, and natural products[108] of almost every Mediterranean people.[109]

In addition to manufacturing, Carthage practised highly advanced and productive agriculture,[110] using iron ploughs, irrigation,[111] and crop rotation. After the Second Punic War, Hannibal promoted agriculture[112] to help restore Carthage's economy and pay the war indemnity to Rome (10,000 talents or 800,000 Roman pounds of silver),[113][114] and he was largely successful. When Rome conquered and destroyed Carthage in 146 BC, the Roman Senate decreed that Mago's famous treatise on agriculture be translated into Latin.[115]

Circumstantial evidence suggests that Carthage developed viticulture and wine production before the 4th century BC,[116] and even exported its wines widely, as indicated by distinctive cigar-shaped Carthaginian amphorae found at archaeological sites around the western Mediterranean,[117] although the contents of these vessels have not been conclusively analysed. Carthage also shipped quantities of raisin wine, the passum of antiquity.[118] Fruits including figs, pears, and pomegranates, as well as nuts, grain, grapes, dates, and olives were grown in the extensive hinterland,[119] while olive oil was processed and exported all over the Mediterranean. Carthage also raised fine horses,[120] the ancestor of today's Barb horses.

Carthage's merchant ships, which surpassed in number even those of the cities of the Levant, visited every major port of the Mediterranean, as well as Britain and the Atlantic coast of Africa.[121] These ships were able to carry over 100 tons of goods.[122]

Carthage also sent caravans into the interior of Africa and Persia. It traded its manufactured and agricultural goods to the coastal and interior peoples of Africa for salt, gold, timber, ivory, ebony, apes, peacocks, skins, and hides.[123] Its merchants invented the practice of sale by auction and used it to trade with the African tribes. In other ports, they tried to establish permanent warehouses or sell their goods in open-air markets. They obtained amber from Scandinavia, and from the Celtiberians, Gauls, and Celts they got amber, tin, silver, and furs. Sardinia and Corsica produced gold and silver for Carthage, and Phoenician settlements on islands such as Malta and the Balearic Islands produced commodities that would be sent back to Carthage for large-scale distribution. The city supplied poorer civilizations with simple products such as pottery, metallic objects, and ornamentations, often displacing the local manufacturing, but brought its best works to wealthier ones such as the Greeks and Etruscans. Carthage traded in almost every commodity wanted by the ancient world, including spices from Arabia, Africa and India, and slaves (the empire of Carthage temporarily held a portion of Europe and sent conquered white warriors into Northern African slavery).[124]

Herodotus wrote an account about 430 BC of Carthaginian trade on the Atlantic coast of Morocco.[125] The Punic explorer and suffete of Carthage called Hanno the Navigator led an expedition to recolonise the Atlantic coast of Morocco[126] that may have ventured as far down the coast of Africa as Senegal and perhaps even beyond. The Greek version of the Periplus of Hanno describes his voyage. Although it is not known just how far his fleet sailed on the African coastline, this short report, dating probably from the 5th or 6th century BC, identifies distinguishing geographic features such as a coastal volcano and an encounter with hairy hominids.

Archaeological finds show evidence of all kinds of exchanges, from the vast quantities of tin needed for a bronze-based metals civilization to all manner of textiles, ceramics and fine metalwork. Before and in between the wars, Carthaginian merchants were in every port in the Mediterranean,[127] trading in harbours with warehouses or from ships beached on the coast.

The Etruscan language is imperfectly deciphered, but bilingual inscriptions found in archaeological excavations at the sites of Etruscan cities indicate the Phoenicians had trading relations with the Etruscans for centuries.[128] The discovery in 1964 at Pyrgi in Italy of a shrine to Astarte, a popular Phoenician deity, containing three gold tablets with inscriptions in Etruscan and Phoenician, gives tangible proof of the Phoenician presence in Italy at the end of the 6th century BC,[129] long before the rise of Rome. These inscriptions imply a political and commercial alliance between Carthage[130] and the Etruscan ruler of Caere that would corroborate Aristotle's statement that the Etruscans and Carthaginians were so close as to form almost one people.[131] The Etruscan city-states were, at times, both commercial partners of Carthage and military allies.[132]

Government

The government of Carthage changed dramatically after the total rout of the Carthaginian forces at the battle of Himera on Sicily in 483 BC.[133]:115–116 The Magonid clan was compelled to compromise and allow representative and even some democratic institutions. Carthage remained to a great extent an oligarchal republic, which relied on a system of checks and balances and ensured a form of public accountability. At the head of the Carthaginian state were now two annually elected, not hereditary, Suffets [133]:130(thus rendered in Latin by Livy 30.7.5, attested in Punic inscriptions as SPΘM /ʃuftˤim/, meaning "judges" and obviously related to the Biblical Hebrew ruler title Shophet "Judge"),[134] similar to modern day executive presidents. Greek and Roman authors more commonly referred to them as "kings". SPΘ /ʃufitˤ/ might originally have been the title of the city's governor, installed by the mother city of Tyre. A list of the hereditary suffetes/"kings" can be found here.

In the historically attested period, the two Suffets were elected annually from among the most wealthy and influential families and ruled collegially, similarly to Roman consuls (and equated with these by Livy). This practice might have descended from the plutocratic oligarchies that limited the Suffet's power in the first Phoenician cities.[135] A range of more junior officials and special commissioners oversaw different aspects of governmental business such as public works, tax-collecting, and the administration of the state treasury.[133]:130[136]

The aristocratic families were represented in a supreme council (Roman sources speak of a Carthaginian "Senate", and Greek ones of a "council of Elders" or a gerousia), which had a wide range of powers; however, it is not known whether the Suffets were elected by this council or by an assembly of the people. Suffets appear to have exercised judicial and executive power, but not military, as generals were chosen by the administration. The final supervision of the Treasury and Foreign Affairs seems to have come under the Council of Elders.[133]:130

There was a body known as the Tribunal of the Hundred and Four, which Aristotle compared to the Spartan ephors[135]:97 These were judges who acted as a kind of higher constitutional court and oversaw the actions of generals[135]:97, who could sometimes be sentenced to crucifixion, as well as other officials. Panels of special commissioners, called pentarchies, were appointed from the Tribunal of One Hundred and Four: they appear to have dealt with a variety of affairs of state.[133]:130

Although the city's administration was firmly controlled by oligarchs [135]:98–100, democratic elements were to be found as well: Carthage had elected legislators, trade unions and town meetings in the form of a Popular Assembly. Aristotle reported in his Politics that unless the Suffets and the Council reached a unanimous decision, the Carthaginian popular assembly had the decisive vote - unlike the situation in Greek states with similar constitutions such as Sparta and Crete. Polybius, in his History book 6, also stated that at the time of the Punic Wars, the Carthaginian public held more sway over the government than the people of Rome held over theirs (a development he regarded as evidence of decline).[137] This may have been due to the influence of the Barcid faction.[133]

Eratosthenes, head of the Library of Alexandria, noted that the Greeks had been wrong to describe all non-Greeks as barbarians, since the Carthaginians as well as the Romans had a constitution. Aristotle also knew and discussed the Carthaginian constitution in his Politics (Book II, Chapter 11).[135]:97–99 During the period between the end of the First Punic War and the end of the Second Punic War, members of the Barcid family dominated in Carthaginian politics.[138] They were given control of the Carthaginian military and all the Carthaginian territories outside of Africa.

Religion

Carthaginian religion was based on Phoenician religion (derived from the faiths of the Levant), a form of polytheism. Many of the gods the Carthaginians worshiped were localized and are now known only under their local names. Carthage also had Jewish communities [139] (which still exist; see Tunisian Jews and Algerian Jews).

Pantheon

The supreme divine couple was that of Tanit and Ba'al Hammon.[140] The goddess Astarte[141] seems to have been popular in early times.[142] At the height of its cosmopolitan era, Carthage seems to have hosted a large array of divinities from the neighbouring civilizations of Greece, Egypt and the Etruscan city-states. A pantheon was presided over by the father of the gods, but a goddess was the principal figure in the Phoenician pantheon.

Caste of priests and acolytes

Surviving Punic texts are detailed enough to give a portrait of a very well organized caste of temple priests and acolytes performing different types of functions, for a variety of prices. Priests were clean shaven, unlike most of the population.[143] In the first centuries of the city ritual celebrations included rhythmic dancing, derived from Phoenician traditions.

Punic stelae

Cippi and stelae of limestone are characteristic monuments of Punic art and religion,[144] found throughout the western Phoenician world in unbroken continuity, both historically and geographically. Most of them were set up over urns containing cremated human remains, placed within open-air sanctuaries. Such sanctuaries constitute striking relics of Punic civilization.

Child sacrifice question

Carthage under the Phoenicians was accused by its adversaries of child sacrifice. Plutarch (20:14,4–6) alleges the practice,[145] as do Tertullian (Apolog.9:2–3),[146] Orosius, Philo and Diodorus Siculus.[147] However, Herodotos and Polybius do not. Skeptics contend that if Carthage's critics were aware of such a practice, however limited, they would have been horrified by it and exaggerated its extent due to their polemical treatment of the Carthaginians.[148] The Hebrew Bible also mentions child sacrifice practiced by the Canaanites, ancestors of the Carthaginians. The Greek and Roman critics, according to Charles Picard, objected not to the killing of children but to the religious nature of it. As in both ancient Greece and Rome, inconvenient children were commonly killed by exposure to the elements. However, the Greeks and Romans engaged in the practice ostensibly out of economic necessity rather than for religious reasons.[149]

Modern archaeology in formerly Punic areas has discovered a number of large cemeteries for children and infants, representing a civic and religious institution for worship and sacrifice called the Tophet by archaeologists. These cemeteries may have been used as graves for stillborn infants or children who died very early.[150] Modern archeological excavations have been interpreted by some archeologists[151] as confirming Plutarch's reports of Carthaginian child sacrifice.[152] An estimated 20,000 urns were deposited between 400 BC and 200 BC,[153] in the tophet discovered in the Salammbô neighbourhood of present-day Carthage with the practice continuing until the early years of the Christian period. The urns contained the charred bones of newborns and in some cases the bones of fetuses and two-year-olds. There is a clear correlation between the frequency of cremation and the well-being of the city. In bad times (war, poor harvests) cremations became more frequent, but it is not known why. One explanation for this correlation is the claim that the Carthaginians prayed for divine intervention (via child sacrifice); however, bad times would naturally lead to increased child mortality, and consequently, more child burials (via cremation).

Accounts of child sacrifice in Carthage report that beginning at the founding of Carthage in about 814 BC, mothers and fathers buried their children who had been sacrificed to Ba`al Hammon and Tanit in the tophet.[133] The practice was apparently distasteful even to Carthaginians, and they began to buy children for the purpose of sacrifice or even to raise servant children instead of offering up their own. However, Carthage's priests demanded the youth in times of crisis or calamity like war, drought or famine. Special ceremonies during extreme crisis saw up to 200 children of the most affluent and powerful families slain and tossed into the burning pyre.[154]

Skeptics maintain that the bodies of children found in Carthaginian and Phoenician cemeteries were merely the cremated remains of children who died naturally. Sergio Ribichini has argued that the tophet was "a child necropolis designed to receive the remains of infants who had died prematurely of sickness or other natural causes, and who for this reason were "offered" to specific deities and buried in a place different from the one reserved for the ordinary dead".[155] The few Carthaginian texts which have survived make absolutely no mention of child sacrifice, though most of them pertain to matters entirely unrelated to religion, such as the practice of agriculture.

See also

- African Empires

- Carthaginian Iberia

- History of Carthage

- History of Tunisia

- Punic Wars

References

- ↑ Martín Lillo Carpio (1992). Historia de Cartagena: De Qart-Ḥadašt a Carthago Nova / colaboradores: Martín Lillo Carpio .... Ed. Mediterráneo. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Nissim R. Ganor; Nissim Raphael Ganor (2009). Who Were the Phoenicians?. Kotarim International Publi. p. 11. ISBN 978-965-91415-2-4.

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati (12 January 2001). "Colonization of the Mediterranean". In Sabatino Moscati. The Phoenicians. I.B.Tauris. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-85043-533-4. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Maria Eugenia Aubet (2008). "Political and Economic Implications of the New Phoenician Chronologies". Universidad Pompeu Fabra. p. 179. Retrieved 24 February 2013. "The recent radiocarbon dates from the earliest levels in Carthage situate the founding of this Tyrian colony in the years 835–800 cal BC, which coincides with the dates handed down by Flavius Josephus and Timeus for the founding of the city."

- ↑ Glenn Markoe (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-520-22614-2. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ John Iliffe (13 August 2007). Africans: The History of a Continent. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-139-46424-6. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ H.H. Scullard (1 September 2010). From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome 133 BC to AD 68. Taylor & Francis. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-415-58488-3. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Hodos, Tamar (June 2009). "Colonial Engagements in the Global Mediterranean Iron Age". Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19 (02): 221–241. doi:10.1017/S0959774309000286.

- ↑ Susan Rebecca Martin (2007). "Hellenization" and Southern Phoenicia: Reconsidering the Impact of Greece Before Alexander. ProQuest. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-549-52890-6. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ A. J. Graham (2001). Collected Papers on Greek Colonization. BRILL. p. 226. ISBN 978-90-04-11634-4. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Eric H. Cline; Mark W. Graham (27 June 2011). Ancient Empires: From Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-521-88911-7. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fred Eugene Ray (2012). Greek and Macedonian Land Battles of the 4th Century B. C.: A History and Analysis of 187 Engagements. McFarland. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-4766-0006-2. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ↑ Mogens Herman Hansen (2000). "Conclusion: The Impact of City-State Cultures on World History". A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. pp. 601–602. ISBN 978-87-7876-177-4. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ Phillip Chiviges Naylor (1 July 2009). North Africa: A History from Antiquity to the Present. University of Texas Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-292-77878-8. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Carl Waldman; Catherine Mason (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. p. 586. ISBN 978-1-4381-2918-1. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World. Infobase Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4381-1020-2. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ P. D. A. Garnsey; C. R. Whittaker (15 February 2007). Imperialism in the Ancient World: The Cambridge University Research Seminar in Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-521-03390-9. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ B. K. Swartz; Raymond E. Dumett (1 January 1980). West African Culture Dynamics: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter. p. 236. ISBN 978-3-11-080068-5. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Richard L. Smith (31 July 2008). Premodern Trade in World History. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-203-89352-4. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Sommer, Michael (1 June 2007). "Networks of Commerce and Knowledge in the Iron Age: The Case of the Phoenicians". Mediterranean Historical Review 22 (1): 1o2. doi:10.1080/09518960701539232.

- ↑ Henry Charles Boren (1992). Roman Society: A Social, Economic, and Cultural History. D.C. Heath. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-669-17801-2. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Robert Rollinger; Christoph Ulf; Kordula Schnegg (2004). Commerce and Monetary Systems in the Ancient World: Means of Transmission and Cultural Interaction : Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Symposium of the Assyrian and Babylonian Intellectual Heritage Project, Held in Innsbruck, Austria, October 3rd - 8th 2002. Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 143. ISBN 978-3-515-08379-9. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ George Rawlinson (30 June 2004). The History Of Phoenicia. Kessinger Publishing. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4191-2402-0. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Arthur M. Eckstein (7 April 2009). Mediterranean Anarchy, Interstate War, and the Rise of Rome. University of California Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-520-93230-2. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Michael R. T. Dumper; Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ P. Roberts (1 October 2004). HSC Ancient History. Pascal Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-74125-179-1. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Allan Chester Johnson; Paul R. Coleman-Norton; Frank Card Bourne (1 October 2003). Ancient Roman Statutes. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-58477-291-0. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Zofia H. Archibald; John Davies; Vincent Gabrielsen; Graham Oliver (26 October 2000). Hellenistic Economies. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-203-99592-1. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Markoe 2000, p.56

- ↑ Matthew Dillon; Lynda Garland (2005). Ancient Rome. Taylor & Francis US. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-415-22458-1. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Maria Eugenia Aubet (6 September 2001). The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies and Trade. Cambridge University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-521-79543-2. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Nigel Bagnall (25 February 2002). The Punic Wars 264-146 BC. Osprey Publishing. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-84176-355-2. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ María Belén Deamos (1 April 1997). Antonio Gilman, ed. Encounters and Transformations: The Archaeology of Iberia in Transition. Lourdes Prados Torreira. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 121–130. ISBN 978-1-85075-593-7. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Michael Dietler; Carolina López-Ruiz (15 October 2009). Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations. University of Chicago Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-226-14848-9. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Garrett G. Fagan; Matthew Trundle (31 July 2010). New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare. BRILL. p. 273. ISBN 978-90-04-18598-2. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Theodore Ayrault Dodge (4 August 2012). "III: Carthaginian Wars. 480-277 BC". Hannibal: A History of the Art of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans Down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., With a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. Tales End Press. ISBN 978-1-62358-005-6. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Richard A. Gabriel (2008). Scipio Africanus: Rome's Greatest General. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59797-998-6. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ Franco De Angelis (2003). Megara Hyblaia and Selinous: the development of two Greek city-states in archaic Sicily. Oxford University, School of Archaeology. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-947816-56-8. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ Fred Eugene Ray (1 January 2009). Land Battles in 5th Century B. C. Greece: A History and Analysis of 173 Engagements. McFarland. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-7864-5260-6. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ John Van Antwerp Fine (1983). The Ancient Greeks: A Critical History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03314-6. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Iain Spence (7 May 2002). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Warfare. Scarecrow Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8108-6612-6. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Andŕew Robert Burn (1984). Persia & the Greeks: The Defense of the West, 546-478 B. C.. Stanford University Press. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-8047-1235-4. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Michael D. Chan (1 December 2006). Aristotle and Hamilton on Commerce and Statesmanship. University of Missouri Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8262-6516-6. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Hanno; Al. N. Oikonomidēs; M. C. J. Miller (1995). Periplus: Or, Circumnavigation (of Africa). Ares Pub. ISBN 978-0-89005-180-1. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Moscati 2001, p.640

- ↑ Daniela Dueck; Kai Brodersen (26 April 2012). Geography in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-19788-5. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Paul Butel (11 March 2002). The Atlantic. Routledge. pp. 11–14. ISBN 978-0-203-01044-0. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ David Soren; Aïcha Ben Abed Ben Khader; Hédi Slim (April 1991). Carthage: uncovering the mysteries and splendors of ancient Tunisia. Simon & Schuster. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-671-73289-9. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Tony Bath (1992). Hannibal's campaigns: the story of one of the greatest military commanders of all time. Barnes & Noble. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-88029-817-9. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Paul B. Kern (1999). Ancient Siege Warfare. Indiana University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-253-33546-3. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Vivian Nutton (20 December 2012). Ancient Medicine. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-415-52094-2. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ David Eggenberger (8 March 2012). An Encyclopedia of Battles: Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles from 1479 B. C. to the Present. Courier Dover Publications. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-486-14201-2. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ P. J. Rhodes (24 August 2011). A History of the Classical Greek World: 478 - 323 BC. John Wiley & Sons. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-4443-5858-2. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Moses I. Finley (1 August 1979). Ancient Sicily. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 104. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Carl J. Richard (1 May 2003). 12 Greeks and Romans who Changed the World. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7425-2791-1. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus, 22:1–22:3

- ↑ Walter Ameling (13 January 2011). "3 The Rise of Carthage to 264 BC - Part I". In Dexter Hoyos. A Companion to the Punic Wars. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9370-5. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Ross Cowan (1 June 2007). For the Glory of Rome: A History of Warriors and Warfare. MBI Publishing Company. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-85367-733-5. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ John M. Kistler; Richard Lair (2007). War Elephants. U of Nebraska Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8032-6004-7. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus , 22:4–22:6

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus , Chapter 23

- ↑ Spencer C. Tucker (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Nigel Bagnall (4 September 2008). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. Random House. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4090-2253-4. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 B. Dexter Hoyos (2007). Truceless War: Carthage's Fight for Survival, 241 to 237. BRILL. p. xiv. ISBN 978-90-04-16076-7. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ John Boardman (18 January 2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Roman World. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-285436-0. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ A. E. Astin; M. W. Frederiksen (29 March 1990). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 566–567. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Gregory Daly (25 September 2003). Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War. Routledge. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-203-98750-6. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Admiral Cyprian Bridges, Sir; Admiral Sir Cyprian G. C. B. Bridges (30 May 2006). Sea-power And Other Studies. Echo Library. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-84702-873-0. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ Michael P. Fronda (10 June 2010). Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy During the Second Punic War. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-139-48862-4. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Kern 1999, p. 269-270

- ↑ Daniel J. Gargola (7 September 2011). "Mediterranean Empire". In Nathan Rosenstein. A Companion to the Roman Republic. Robert Morstein-Marx. John Wiley & Sons. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4443-5720-2. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 David Abulafia (13 October 2011). The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-19-532334-4. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa (1981). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. University of California Press. p. 460. ISBN 978-0-435-94805-4. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ J. D. Fage (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Dillon Garland 2005, p.228

- ↑ Duncan Campbell; Adam Hook (8 May 2005). Siege Warfare in the Roman World: 146 BC-AD 378. Osprey Publishing. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-84176-782-6. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ George Mousourakis (30 July 2007). A Legal History of Rome. Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-203-08934-7. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Stefan Weninger (23 December 2011). Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. p. 420. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Robert M. Kerr (12 August 2010). Latino-Punic Epigraphy: A Descriptive Study of the Inscriptions. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-3-16-150271-2. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics Book 3,IX

- ↑ Barry W. Cunliffe (24 May 2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-19-285441-4. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Markoe 2000, p.103

- ↑ Jack Goody (15 November 2012). Metals, Culture and Capitalism: An Essay on the Origins of the Modern World. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-107-02962-0. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Lionel Casson (1991). The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-691-01477-7. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Duane W. Roller (2006). Through the Pillars of Herakles: Greco-Roman Exploration of the Atlantic. Taylor & Francis US. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-415-37287-9. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ María Eugenia Aubet Semmler (2002). "The Tartessian Orientalizing Period". In Marilyn R. Bierling. The Phoenicians in Spain: An Archaeological Review of the Eighth-Sixth Centuries B.C.E. : a Collection of Articles Translated from Spanish. Seymour Gitin. Eisenbrauns. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-1-57506-056-9. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Pliny, Nat His 33,96

- ↑ Karl Moore; David Lewis (20 April 2009). The Origins of Globalization. Taylor & Francis. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-415-80598-8. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ H.S. Geyer (1 January 2009). International Handbook of Urban Policy: Issues in the Developed World. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-84980-202-4. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ SorenKhader 1991, p. 90.

- ↑ Gilbert Charles-Picard; Colette Charles-Picard (1961). Daily Life in Carthage at the Time of Hannibal. George Allen and Unwin. p. 46. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Excavations at Carthage. University of Michigan, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. 1977. p. 145. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Libyan Studies: Annual Report of the Society for Libyan Studies. The Society. 1983. p. 83. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography XVII, 3, 18.

- ↑ Edward Lipiński (2004). Itineraria Phoenicia. Peeters Publishers. p. 354. ISBN 978-90-429-1344-8. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Brian Herbert Warmington (1993). Carthage. Barnes & Noble Books. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-56619-210-1. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Judith Lynn Sebesta (1994). Judith Lynn Sebesta, ed. The World of Roman Costume. Larissa Bonfante. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-299-13854-7. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ SebestaBonfante 1994, pp.13-15

- ↑ John R. Clarke (2003). Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 315. University of California Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-520-21976-2. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Aïcha Ben Abed Ben Khader (2006). Tunisian Mosaics: Treasures from Roman Africa. Getty Publications. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-89236-857-0. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Irmtraud Reswick (1985). Traditional textiles of Tunisia and related North African weavings. Craft & Folk Art Museum. p. 18. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ J. D. Fage (1 February 1979). From 500 B. C. to A. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Warmington 1993, p.136

- ↑ Stefan Goodwin (15 October 2008). Africas Legacy of Urbanization: Unfolding Saga of a Continent. Lexington Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7391-5176-1. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ William E. Dunstan (16 November 2010). Ancient Rome. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Luc-Normand Tellier (1 January 2009). Urban World History: An Economic and Geographical Perspective. PUQ. p. 146. ISBN 978-2-7605-2209-1. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Peter I. Bogucki (2008). Encyclopedia of society and culture in the ancient world. Facts On File. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-8160-6941-5. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Bogucki 2008, p.290

- ↑ Alan Lloyd (June 1977). Destroy Carthage!: the death throes of an ancient culture. Souvenir Press. p. 96. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Peter Alexander René van Dommelen; Carlos Gómez Bellard; Roald F. Docter (2008). Rural Landscapes of the Punic World. Isd. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84553-270-3. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ John B. Thornes; John Wainwright (25 September 2003). Environmental Issues in the Mediterranean: Processes and Perspectives from the Past and Present. Routledge. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-203-49549-0. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ Nic Fields; Peter Dennis (15 February 2011). Hannibal. Osprey Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-84908-349-2. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Pliny 33,51

- ↑ Christopher S. Mackay (2004). Ancient Rome. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-80918-4. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Nathan Rosenstein; Robert Morstein-Marx (1 February 2010). A Companion to the Roman Republic. John Wiley & Sons. p. 470. ISBN 978-1-4443-3413-5. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Patrick E. McGovern; Stuart J. Fleming; Solomon H. Katz (19 June 2004). The Origins and Ancient History of Wine: Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology. Routledge. pp. 324–326. ISBN 978-0-203-39283-6. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Smith 2008, p. 66

- ↑ Andrew Dalby (2003). Food in the Ancient World: From A to Z. Psychology Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-415-23259-3. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Jean Louis Flandrin; Massimo Montanari (1999). Food: Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present. Columbia University Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-231-11154-6. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Fran Lynghaug (15 October 2009). The Official Horse Breeds Standards Guide: The Complete Guide to the Standards of All North American Equine Breed Associations. Voyageur Press. p. 551. ISBN 978-1-61673-171-7. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Fage 1975, p. 296

- ↑ Illustrated Encyclopaedia of World History. Mittal Publications. p. 1639. GGKEY:C6Z1Y8ZWS0N. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Bogucki 2008, p. 390

- ↑ Dierk Lange (2004). Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa: Africa-centred and Canaanite-Israelite Perspectives : a Collection of Published and Unpublished Studies in English and French. J.H.Röll Verlag. p. 278. ISBN 978-3-89754-115-3. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ G. Mokhtar (1981). Ancient civilizations of Africa: 2. UNESCO. pp. 448–449. ISBN 978-92-3-101708-7. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Lipiński 2004, pp. 435-437

- ↑ Amy McKenna (15 January 2011). The History of Northern Africa. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-61530-318-2. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Susan Raven (1 November 2002). Rome in Africa. Psychology Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-203-41844-4. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Giuliano Bonfante; Larissa Bonfante (2002). The Etruscan Language: An Introduction, Revised Editon. Manchester University Press. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-0-7190-5540-9. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Brian Caven (1990). Dionysius I: War-Lord of Sicily. Yale University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-300-04507-9. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ BonfanteBonfante 2002, p.68

- ↑ Sybille Haynes (1 September 2005). Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. Getty Publications. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-89236-600-2. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 133.2 133.3 133.4 133.5 133.6 Richard Miles (21 July 2011). Carthage Must Be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Civilization. Penguin. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-1-101-51703-1. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Moises Silva (11 May 2010). Biblical Words and Their Meaning: An Introduction to Lexical Semantics. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-87151-4. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 135.2 135.3 135.4 Aristotle (5 November 2012). Politics: A Treatise on Government. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-4802-6588-2. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Aristotle. p. 2.11.3–70.

- ↑ Craige B. Champion (2004). Cultural Politics in Polybius's Histories. University of California Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-520-92989-0. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ J.C. Yardley (25 June 2009). Hannibal's War:. Oxford University Press. pp. xiv–xvi. ISBN 978-0-19-162330-1. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Dan Jaffé (31 July 2010). Studies in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity: Text and Context. BRILL. p. 221. ISBN 978-90-04-18410-7. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Ephraim Stern; William G. Dever (November 2006). "Goddesses and Cults at Tel Dor". In Seymour Gitin,. Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever. J. Edward Wright, J. P. Dessel. Eisenbrauns. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-57506-117-7. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Frank Moore Cross (30 June 2009). Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Harvard University Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-674-03008-4. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Fernand Braudel (9 February 2011). "6: Colonization: The Discovery of the Mediterranean "Far West" in the Tenth to Sixth Centuries B.C". Memory and the Mediterranean. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-307-77336-4. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Charles-Picard Charles-Picard 1961, p.131

- ↑ D. M. Lewis; John Boardman; Simon Hornblower; M. Ostwald (13 October 1994). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 375–377. ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Plutarch (July 2004). Plutarch on the Delay of the Divine Justice. Kessinger Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4179-2911-5. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Aubet 2001 p.249

- ↑ Diodorus (1970). The library of history: Books IV.59-VIII. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99375-4. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Serge Lancel (13 October 1999). Hannibal. Wiley. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-631-21848-7. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Gilbert Charles-Picard; Colette Charles-Picard (1968). The life and death of Carthage: a survey of Punic history and culture from its birth to the final tragedy. Pan Macmillan. pp. 46–48, 153. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Carhtage a History, S Lancel, trans A Nevill, pp251

- ↑ Susanna Shelby Brown (1991). Late Carthaginian child sacrifice and sacrificial monuments in their Mediterranean context. JSOT. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-85075-240-0. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Eric M. Meyers; American Schools of Oriental Research (1997). The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East. Oxford University Press. p. 159. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Aubet 2001, p. 252.

- ↑ F. W. Walbank; R. M. Ogilvie; M. W. Frederiksen (29 March 1990). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 514. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Moscati 2001, p. 141