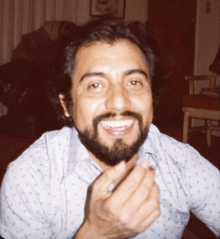

Carlos Almaraz

Carlos Almaraz (October 5, 1941 – December 11, 1989) was a Mexican-American artist and an early proponent of the Chicano street arts movement.

Childhood and education

Almaraz was born in Mexico City, but his family moved when he was a young child, settling in Chicago, Illinois, where his father owned a restaurant for five years and worked in Gary steel mills for another four. The neighborhood Almaraz and his brother were raised in was multicultural, which led him to appreciate the melting pot of American culture.[1] During his youth in Chicago, the family traveled to Mexico City frequently, where Almaraz reports having his "first impression of art" that "was both horrifying and absolutely magical". A painting of John the Baptist in the Mexico City cathedral appeared as a gorilla to his young eye and frightened him, but it also taught him "that art can be something almost alive." When Almaraz was nine his family moved to Los Angeles on a doctor's recommendation that his father seek a warm climate to assuage his rheumatism, and also as a result of family problems, first settling in Wilmington, later moving to the then-rural Chatsworth, where they lived in communal housing with other Mexicans.[1] The family then relocated to a Mexican "colony" of the nearly-all-white Beverly Hills, and still later to the barrio of East Los Angeles. Almaraz's interest in the arts, nascent in Chicago, blossomed after his family moved to California, and the sense of mobility developed after so many moves later allowed him to connect with migrant farmworkers and their children. He graduated from Garfield High School in 1959 and attended Los Angeles City College, studying under David Ramirez, and took summer classes at Loyola Marymount University. Loyola offered him a full scholarship, but he declined it in protest of the University's support of the Vietnam War and stopped professing the Catholic faith altogether. He attended California State University, Los Angeles but became discouraged by the structure of the art department there, "because there was no place for an artist." While at CSULA, Almaraz began attending night courses at the Otis College of Art and Design, then known as Otis Art Institute, studying under Joe Mugnaini.[1]

Almaraz studied arts at UCLA. In 1974, he earned an MFA from the Otis Art Institute (now known as Otis College of Art and Design).

Career

In 1961, Almaraz moved to New York city, with Dan Guerrero, the son of Lalo Guerrero. He left after six months to take advantage of a scholarship offered him by Otis Art Institute. He returned to New York and lived there from 1966 to 1969, where he struggled as a painter in the middle of the new wave movements of the era.

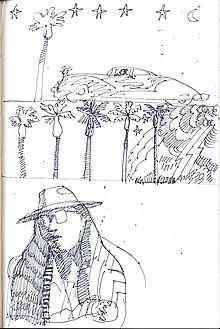

While in New York, he also wrote poetry and philosophy. Almaraz's poems and philosophical views have been published in fifty books.

After returning to California, Almaraz almost died in 1971, and was given the last rites. It has been said that he had an experience with God during his convalescence.[2] In 1973, he was one of four artists who formed the influential artist collective known as Los Four. In 1974, Judithe Hernández, who was a friend and classmate from graduate school at Otis Art Institute became the "fifth member" and the only woman in Los Four.[3] With the addition of Hernández, the collective exhibited and created public art together for the next decade and have been credited with bringing Chicano art to the attention of mainstream American art institutions.

Almaraz then went on to work for famed Arizonan and fellow Chicano Cesar Chavez, painting murals, banners and other types of paintings for Chavez's United Farm Workers. He also painted for Luis Valdez's Teatro Campesino.[1]

His "Echo Park" series of paintings, named after a Los Angeles park of the same name, became known worldwide and have been displayed in many museums internationally. On November 12, 1978, Almaraz wrote "Because love is not found in Echo Park, I'll go where it is found". While Almaraz may not have found love at Echo Park, he certainly found inspiration to produce paintings there: he lived close to the park, having a clear view of the park from his apartment's window.[1]

Another of Almaraz's works, named "Boycott Gallo", became a cultural landmark in the community of East Los Angeles.[1] During the late 1980s, however, "Boycott Gallo" was brought down.

Almaraz was married to Elsa Flores, Chicana activist and photographer. Together, the pair produced "California Dreamscape". He exhibited his work at the Jan Turner Gallery starting in the mid-1980s in Los Angeles through his passing.

Carlos Almaraz died in 1989 of AIDS-related causes. He is remembered as an artist who used his talent to bring critical attention to the early Chicano Art Movement, as well as a supporter of Cesar Chávez and the UFW. His work continues to enjoy popularity. In 1992 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art honored him with a tribute featuring 28 of his drawings and prints donated by his widow.[4] Flores continues to represent his estate. An exhibition of his paintings, pastels, and drawings from the 70s and 80s opened in September 2011, in conjunction with the Getty Research Institute's "Pacific Standard Time: Art in LA 1945-1980". Almaraz will also be featured in corresponding "Pacific Standard Time" exhibitions, including “MEX/LA: Mexican Modernism(s) in Los Angeles 1930-1985” at the Museum of Latin American Art, “Mapping Another L.A.: The Chicano Art Movement” at the Fowler Museum.[5] His and Flores's papers are preserved at the Smithsonian.[6]

Quote

- "Art is a record, a document, that you leave behind showing what you saw and felt when you were alive. That's all"- Carlos Almaraz, March 4, 1969.

See also

- List of notable Chicanos

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Oral history interview with Carlos Almaraz, 1986 Feb. 6-1987 Jan. 29, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ↑ "artscenecal.com Carlos Almarez page". Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ↑ "Oral history interview with Judithe Hernández, 1998 Mar. 28, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Snow, Shauna (1 April 1992). "LACMA Sets Tribute to Carlos Almaraz : Art: The upcoming showcase features 28 drawings and prints donated by the artist's widow, plus two of his major paintings. The exhibition opens in June". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ http://pacificstandardtime.org/exhibitions

- ↑ "Carlos Almaraz and Elsa Flores papers, 1946-1996". Retrieved 29 July 2011.

External links

- artscenecal.com

- Almaraz in the permanent collection at LACMA

- Art of Aztlan Gallery

- Print Retrospective Exhibition

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|