Cardia

| Cardia | |

|---|---|

| |

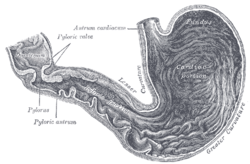

| Diagram from cancer.gov: * 1. Body of stomach * 2. Fundus * 3. Anterior wall * 4. Greater curvature * 5. Lesser curvature * 6. Cardia * 9. Pyloric sphincter * 10. Pyloric antrum * 11. Pyloric canal * 12. Angular notch * 13. Gastric canal * 14. Rugal folds | |

| |

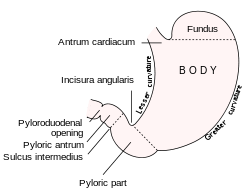

| Diagram of the stomach, showing its anatomical landmarks ("Antrum cardiacum" marks the opening of the cardia). | |

| Latin | Pars cardiaca gastris, pars cardiaca ventriculi |

| Gray's | subject #247 1162 |

The cardia is the anatomical term for the part of the stomach attached to the esophagus. The cardia begins immediately distal to the z-line of the gastroesophageal junction, where the squamous epithelium of the esophagus gives way to the columnar epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract.[1]

Near the cardia at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction is the anatomically indistinct but physiologically demonstrable lower esophageal sphincter.[2] The area termed the cardia overlaps with the lower esophageal sphincter;[1] however, the cardia does not contain the lower esophageal sphincter. Although the topic was previously disputed, current consensus states that the cardia is part of the stomach.[2][3]

The cardia overlaps with but specifically does not contain the lower esophageal sphincter (LES)[1] (also termed cardiac sphincter,[4] gastroesophageal sphincter, and esophageal sphincter[5]). This is in contrast to the "upper esophageal sphincter" contained in the hypopharynx (area extending from the base of the tongue to the cricoid cartilage) and consists of striated muscle controlled by somatic innervation.[1]

The z-line is usually within the LES, thus LES can be identified by z-line color that changes from salmon pink to a deeper red.[6] But, a study correlating manometric and endoscopic localization of the LES (z-line) found that the functional location of LES was 3 cm distal to the z-line. [7]

Nomenclature and classification

There were previously conflicting statements in the academic anatomy community[8][9][10] over whether the cardia is part of the stomach, part of the esophagus or a distinct entity. Modern surgical and medical textbooks have agreed that "The gastric cardia is now clearly considered to be part of the stomach."[1][3]

Classical anatomy textbooks, and some other resources,[11] describe the cardia as the first of 4 regions of the stomach. This makes sense histologically because the mucosa of the cardia is the same as that of the stomach.

Function

The stomach generates strong acids (HCl) and enzymes (such as pepsin) to aid in food digestion. This digestive mixture is called gastric juice. The inner lining of the stomach has several mechanisms to resist the effect of gastric juice on itself, but the mucosa of the esophagus does not. The esophagus is normally protected from these acids by a one-way valve mechanism at its junction with the stomach. This one-way valve is called the esophageal sphincter (ES), and this, along with the angle of His formed here, prevents gastric juice from flowing back into the esophagus.

During peristalsis, the ES allows the food bolus to pass into the stomach. It prevents chyme, a mixture of bolus, stomach acid, and digestive enzymes, from returning up the esophagus. The ES is aided in the task of keeping the flow of materials in one direction by the diaphragm.

The ES is a functional sphincter but not an anatomical sphincter. [citation needed] That is to say, though there is no thickening of the smooth muscle, as in the pyloric sphincter, chyme is (usually) prevented from travelleling back from the stomach up the esophagus. The lower crus of the diaphragm helps this sphincteric action. [12]

Histology

On histological examination, the junction can be identified by the following transition:[13][14]

- nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium in the esophagus

- simple columnar epithelium in the stomach

However, in Barrett's esophagus, the epithelial distinction may vary, so the histological border may not be identical with the functional border.

The cardiac glands can be seen in this region. They can be distinguished from other stomach glands (fundic glands and pyloric glands) because the glands are shallow and simple tubular.

Pathology

Deficiencies in the strength or the efficiency of the LES lead to various medical problems involving acid damage on the esophagus.

In achalasia, one of the defects is failure of the LES to relax properly; causing Megaesophagus.

Removal

Surgical removal of this area is a called a "cardiactomy". "Cardiectomy" is a term that is also used to describe removal of the heart.[15][16][17]

Etymology

The word comes from the Greek kardia meaning heart, the cardiac orifice of the stomach.

See also

- Artificial cardia, that can be used to fight, between other diseases, esophageal cancer, achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

- Pylorus

Additional images

-

-

Section of mucous membrane of human stomach, near the cardiac orifice. X 45.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Barrett KE, "Chapter 7. Esophageal Motility" (Chapter). Barrett KE: Gastrointestinal Physiology: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2307248

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Template:Isbn 0071547703

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Template:Isbn 0071434143

- ↑ cardiac+sphincter at eMedicine Dictionary

- ↑ Patient Handout: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- ↑ Gastrointestinal disease: an endoscopic approach, By Anthony J. DiMarino, p.166

- ↑ GI Motility online (2006-05-16). "Esophagus - anatomy and development : GI Motility online". Nature.com. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ↑ Digestive Disease Library

- ↑ Department of Physiology and Cell Biology

- ↑ med/2965 at eMedicine

- ↑ 37:06-0103 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Abdominal Cavity: The Stomach"

- ↑ USA (2013-03-25). "Neuromuscular Anatomy of Esophagus and Lower Esophageal Sphincter - Motor Function of the Pharynx, Esophagus, and its Sphincters - NCBI Bookshelf". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ↑ BU Histology Learning System: 11101loa

- ↑ BU Histology Learning System: 11111ooa

- ↑ cardiectomy at dictionary.reference.com

- ↑ O. W. BARLOW (1929). "THE SURVIVAL OF THE CIRCULATION IN THE FROG WEB AFTER CARDIECTOMY". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 35 (1): 17–24. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ↑ S.J. MELTZER (1913). THE EFFECT OF STRYCHNIN IN CARDIECTOMIZED FROGS WITH DESTROYED LYMPH HEARTS. American Journal of Physiology. pp. xix.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||