Carbon suboxide

| Carbon suboxide | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| IUPAC name Propa-1,2-diene-1,3-dione | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 504-64-3 |

| PubChem | 136332 |

| ChemSpider | 120106 |

| MeSH | Carbon+suboxide |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30086 |

| Jmol-3D images | Image 1 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

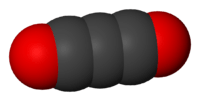

| Molecular formula | C3O2 |

| Molar mass | 68.03 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | colorless gas strong, pungent odor |

| Density | 0.906 ± 0.06 g cm−3, gas at 298 K |

| Melting point | −111.3 °C, 161.9 K |

| Boiling point | 6.8 °C, 280.0 K |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.4538 (0 °C) |

| Structure | |

| Molecular shape | linear |

| Related compounds | |

| Related oxides | carbon dioxide carbon monoxide dicarbon monoxide |

| Related compounds | carbon subsulfide carbon subnitride |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| Infobox references | |

Carbon suboxide, or tricarbon dioxide, is an oxide of carbon with chemical formula C3O2 or O=C=C=C=O. Its four cumulative double bonds make it a cumulene. It is one of the stable members of the series of linear oxocarbons O=Cn=O, which also includes carbon dioxide (CO2) and pentacarbon dioxide (C5O2).

The substance was discovered in 1873 by Benjamin Brodie by subjecting carbon monoxide to an electric current. He claimed that the product was part of a series of "oxycarbons" with formulas Cx+1Ox, namely C, C2O, C3O2, C4O3, C5O4, ..., and to have identified the last two;[1][2] however only C3O2 is known. In 1891 Marcellin Berthelot observed that heating pure carbon monoxide at about 550 °C created small amounts of carbon dioxide but no trace of carbon, and assumed that a carbon-rich oxide was created instead, which he named "sub-oxide". He assumed it was the same product obtained by electric discharge and proposed the formula C2O.[3] Otto Diels later stated that the more organic names dicarbonyl methane and dioxallene were also correct.

It is commonly described as an oily liquid or gas at room temperature with an extremely noxious odor.[4]

Synthesis

It is synthesized by warming a dry mixture of phosphorus pentoxide (P4O10) and malonic acid or the esters of malonic acid.[5] Therefore, it can be also considered as the anhydride of malonic anhydride, i.e. the "second anhydride" of malonic acid. Malonic anhydride (not to be confused with maleic anhydride) is a real molecule.[6]

Several other ways for synthesis and reactions of carbon suboxide can be found in a review from 1930 by Reyerson.[7]

Carbon suboxide polymerizes spontaneously to a red, yellow, or black solid. The structure is postulated to be poly(α-pyronic), similar to the structure in 2-pyrone (α-pyrone).[8][9] In 1969, it was hypothesized that the color of Martian surface was caused by this compound; this was disproved by the Viking Mars probes.[10]

Uses

Carbon suboxide is used in the preparation of malonates; and as an auxiliary to improve the dye affinity of furs.

References

- ↑ Brodie, B. C. (1873). "Note on the Synthesis of Marsh-Gas and Formic Acid, and on the Electric Decomposition of Carbonic Oxide" (pdf). Proceedings of the Royal Society 21 (139–147): 245–247. doi:10.1098/rspl.1872.0052. JSTOR 113037. "When pure and dry carbonic oxide [=carbon monoxide] is circulated through the induction-tube, and there submitted to the action of electricity, a decomposition of the gas occurs [...] Carbonic acid [=carbon dioxide] is formed, and simultaneously with its formation a solid deposit may be observed in the induction-tube. This deposit appears as a transparent film of a red-brown color, lining the walls of the tube. It is perfectly soluble in water, which is strongly colored by it. The solution has an intensely acid reaction. The solid deposit, in the dry condition before it has been in contact with the water, is an oxide of carbon."

- ↑ Brodie, B. C. (1873). "Ueber eine Synthese von Sumpfgas und Ameisensäure und die electrische Zersetzung des Kohlenoxyds". Annalen der Chemie 169 (1–2): 270–271. doi:10.1002/jlac.18731690119.

- ↑ Berthelot, M. (1891). "Action de la chaleur sur l'oxyde de carbone". Annales de Chimie et de Physique 6 (24): 126–132.

- ↑ Reyerson, L. H.; Kobe, K. (1930). "Carbon Suboxide". Chemical Reviews 7 (4): 479–492. doi:10.1021/cr60028a002.

- ↑ Diels, O.; Wolf, B. (1906). "Ueber das Kohlensuboxyd. I". Chemische Berichte 39: 689–697. doi:10.1002/cber.190603901103.

- ↑ Perks, H. M.; Liebman, J. F. (2000). "Paradigms and Paradoxes: Aspects of the Energetics of Carboxylic Acids and Their Anhydrides". Structural Chemistry 11 (4): 265–269. doi:10.1023/A:1009270411806.

- ↑ Reyerson, L. H.; Kobe, K. (1930). "Carbon Suboxide". Chemical Reviews 7 (4): 479–492. doi:10.1021/cr60028a002.

- ↑ Ballauff, M.; Li, L.; Rosenfeldt, S.; Dingenouts, N.; Beck, J.; Krieger-Beck, P. (2004). "Analysis of Poly(carbon suboxide) by Small-Angle X-ray Scattering". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 43 (43): 5843–5846. doi:10.1002/anie.200460263. PMID 15523711.

- ↑ Ellern, A.; Drews, T.; Seppelt, K. (2001). "The Structure of Carbon Suboxide, C3O2, in the Solid State". Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie 627 (1): 73–76. doi:10.1002/1521-3749(200101)627:1<73::AID-ZAAC73>3.0.CO;2-A.

- ↑ Plummer, W. T.; Carsont, R. K. (1969). "Mars: Is the Surface Colored by Carbon Suboxide?". Science 166 (3909): 1141–1142. doi:10.1126/science.166.3909.1141. PMID 17775571.

External links

| ||||||||||||||