Capillary action

Capillary action (sometimes capillarity, capillary motion, or wicking) is the ability of a liquid to flow in narrow spaces without the assistance of, and in opposition to, external forces like gravity. The effect can be seen in the drawing up of liquids between the hairs of a paint-brush, in a thin tube, in porous materials such as paper, in some non-porous materials such as liquified carbon fiber, or in a cell. It occurs because of intermolecular forces between the liquid and surrounding solid surfaces. If the diameter of the tube is sufficiently small, then the combination of surface tension (which is caused by cohesion within the liquid) and adhesive forces between the liquid and container act to lift the liquid. In short, the capillary action is due to the pressure of cohesion and adhesion which cause the liquid to work against gravity.[1]

History

Albert Einstein's first paper[2] submitted in 1900 to Annalen der Physik was on capillarity. It was titled Folgerungen aus den Kapillaritätserscheinungen, which was translated as Conclusions from the capillarity phenomena, found in volume 4, page 513 (published in 1901).

Phenomena and physics of capillary action

A common apparatus used to demonstrate the first phenomenon is the capillary tube. When the lower end of a vertical glass tube is placed in a liquid, such as water, a concave meniscus forms. Adhesion occurs between the fluid and the solid inner wall pulling the liquid column up until there is a sufficient mass of liquid for gravitational forces to overcome these intermolecular forces. The contact length (around the edge) between the top of the liquid column and the tube is proportional to the diameter of the tube, while the weight of the liquid column is proportional to the square of the tube's diameter. So, a narrow tube will draw a liquid column higher than a wider tube will.

In plants and trees

The capillary action is enhanced in trees by branching, evaporation at the leaves creating depressurization, and probably by osmotic pressure added at the roots and possibly at other locations inside the plant, especially when gathering humidity with air roots.[3][4]

Examples

Capillary action is essential for the drainage of constantly produced tear fluid from the eye. Two canaliculi of tiny diameter are present in the inner corner of the eyelid, also called the lacrimal ducts; their openings can be seen with the naked eye within the lacrymal sacs when the eyelids are everted.

Wicking is the absorption of a liquid by a material in the manner of a candle wick. Paper towels absorb liquid through capillary action, allowing a fluid to be transferred from a surface to the towel. The small pores of a sponge act as small capillaries, causing it to absorb a comparatively large amount of fluid. Some textile fabrics are said to use capillary action to "wick" sweat away from the skin. These are often referred to as wicking fabrics, after the capillary properties of candle and lamp wicks.

Capillary action is observed in thin layer chromatography, in which a solvent moves vertically up a plate via capillary action. In this case the pores are gaps between very small particles.

Capillary action draws ink to the tips of fountain pen nibs from a reservoir or cartridge inside the pen.

With some pairs of materials, such as mercury and glass, the intermolecular forces within the liquid exceed those between the solid and the liquid, so a convex meniscus forms and capillary action works in reverse.

In hydrology, capillary action describes the attraction of water molecules to soil particles. Capillary action is responsible for moving groundwater from wet areas of the soil to dry areas. Differences in soil potential ( ) drive capillary action in soil.

) drive capillary action in soil.

Height of a meniscus

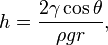

The height h of a liquid column is given by:[5]

where  is the liquid-air surface tension (force/unit length), θ is the contact angle, ρ is the density of liquid (mass/volume), g is local acceleration due to gravity (length/square of time[6]), and r is radius of tube (length). Thus the thinner the space in which the water can travel, the further up it goes.

is the liquid-air surface tension (force/unit length), θ is the contact angle, ρ is the density of liquid (mass/volume), g is local acceleration due to gravity (length/square of time[6]), and r is radius of tube (length). Thus the thinner the space in which the water can travel, the further up it goes.

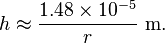

For a water-filled glass tube in air at standard laboratory conditions, γ = 0.0728 N/m at 20 °C, θ = 0° (cos(0) = 1), ρ is 1000 kg/m3, and g = 9.81 m/s2. For these values, the height of the water column is

Thus for a 4 m (13 ft) diameter glass tube in lab conditions given above (radius 2 m (6.6 ft)), the water would rise an unnoticeable 0.007 mm (0.00028 in). However, for a 4 cm (1.6 in) diameter tube (radius 2 cm (0.79 in)), the water would rise 0.7 mm (0.028 in), and for a 0.4 mm (0.016 in) diameter tube (radius 0.2 mm (0.0079 in)), the water would rise 70 mm (2.8 in).

Liquid transport in porous media

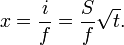

When a dry porous medium, such as a brick or a wick, is brought into contact with a liquid, it will start absorbing the liquid at a rate which decreases over time. For a bar of material with cross-sectional area A that is wetted on one end, the cumulative volume V of absorbed liquid after a time t is

where S is the sorptivity of the medium, with dimensions m/s1/2 or mm/min1/2. The quantity

is called the cumulative liquid intake, with the dimension of length. The wetted length of the bar, that is the distance between the wetted end of the bar and the so-called wet front, is dependent on the fraction f of the volume occupied by liquid. This number f is the porosity of the medium; the wetted length is then

Some authors use the quantity S/f as the sorptivity.[7] The above description is for the case where gravity and evaporation do not play a role.

Sorptivity is a relevant property of building materials, because it affects the amount of rising dampness. Some values for the sorptivity of building materials are in the table below.

| Material | Sorptivity (mm min-1/2) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Aerated concrete | 0.54 | [8] |

| Gypsum plaster | 3.50 | [8] |

| Clay brick | 1.16 | [8] |

See also

| Continuum mechanics |

|---|

|

- Bound water

- Capillary fringe

- Capillary pressure

- Capillary wave

- Damp-proof course

- Frost flowers

- Frost heaving

- Hindu milk miracle

- Needle ice

- Surface tension

- Washburn's equation

- Water

- Wick effect

- Young–Laplace equation

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capillary action. |

- ↑ "Capillary Action - Liquid, Water, Force, and Surface - JRank Articles". Science.jrank.org. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ↑ Hans-Josef Kuepper. "List of Scientific Publications of Albert Einstein". Einstein-website.de. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ↑ Tree physics at "Neat, Plausible And" scientific discussion website.

- ↑ Water in Redwood and other trees, mostly by evaporation article at wonderquest website.

- ↑ G.K. Batchelor, 'An Introduction To Fluid Dynamics', Cambridge University Press (1967) ISBN 0-521-66396-2

- ↑ Hsai-Yang Fang, john L. Daniels, Introductory Geotechnical Engineering: An Environmental Perspective

- ↑ C. Hall, W.D. Hoff, Water transport in brick, stone, and concrete. (2002) page 131 on Google books

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Hall and Hoff, p. 122