Canonical form

In mathematics and computer science, a canonical, normal, or standard form of a mathematical object is a standard way of presenting that object as a mathematical expression. The distinction between "canonical" and "normal" forms varies by subfield. In most fields, a canonical form specifies a unique representation for every object, while a normal form simply specifies its form, without the requirement of uniqueness.

The canonical form of a positive integer in decimal representation is a finite sequence of digits that does not begin with zero.

More generally, for a class of objects on which an equivalence relation (which can differ from standard notions of equality, for instance by considering different forms of equal objects to be nonequivalent) is defined, a canonical form consists in the choice of a specific object in each class. For example, row echelon form and Jordan normal form are canonical forms for matrices.

In computer science, and more specifically in computer algebra, when representing mathematical objects in a computer, there are usually many different ways to represent the same object. In this context, a canonical form is a representation such that every object has a unique representation. Thus, the equality of two objects can easily be tested by testing the equality of their canonical forms. However canonical forms frequently depend on arbitrary choices (like ordering the variables), and this introduces difficulties for testing the equality of two objects resulting on independent computations. Therefore, in computer algebra, normal form is a weaker notion: A normal form is a representation such that zero is uniquely represented. This allows to test equality by putting the difference of two objects in normal form (see Computer algebra#Equality).

Canonical form can also mean a differential form that is defined in a natural (canonical) way; see below.

Finding a canonical form is called canonization. In some branches of computer science the term canonicalization is adopted.

Definition

Suppose we have some set S of objects, with an equivalence relation. A canonical form is given by designating some objects of S to be "in canonical form", such that every object under consideration is equivalent to exactly one object in canonical form. In other words, the canonical forms in S represent the equivalence classes, once and only once. To test whether two objects are equivalent, it then suffices to test their canonical forms for equality. A canonical form thus provides a classification theorem and more, in that it not just classifies every class, but gives a distinguished (canonical) representative.

In practical terms, one wants to be able to recognize the canonical forms. There is also a practical, algorithmic question to consider: how to pass from a given object s in S to its canonical form s*? Canonical forms are generally used to make operating with equivalence classes more effective. For example in modular arithmetic, the canonical form for a residue class is usually taken as the least non-negative integer in it. Operations on classes are carried out by combining these representatives and then reducing the result to its least non-negative residue. The uniqueness requirement is sometimes relaxed, allowing the forms to be unique up to some finer equivalence relation, like allowing reordering of terms (if there is no natural ordering on terms).

A canonical form may simply be a convention, or a deep theorem.

For example, polynomials are conventionally written with the terms in descending powers: it is more usual to write x2 + x + 30 than x + 30 + x2, although the two forms define the same polynomial. By contrast, the existence of Jordan canonical form for a matrix is a deep theorem.

Examples

Note: in this section, "up to" some equivalence relation E means that the canonical form is not unique in general, but that if one object has two different canonical forms, they are E-equivalent.

Linear algebra

| Objects | A is equivalent to B if: | Normal form | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal matrices over the complex numbers |  for some unitary matrix U for some unitary matrix U |

Diagonal matrices (up to reordering) | This is the Spectral theorem |

| Matrices over the complex numbers |  for some unitary matrices U and V for some unitary matrices U and V |

Diagonal matrices with real positive entries (in descending order) | Singular value decomposition |

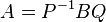

| Matrices over an algebraically closed field |  for some invertible matrix P for some invertible matrix P |

Jordan normal form (up to reordering of blocks) | |

| Matrices over an algebraically closed field |  for some invertible matrix P for some invertible matrix P |

Weyr canonical form (up to reordering of blocks) | |

| Matrices over a field |  for some invertible matrix P for some invertible matrix P |

Frobenius normal form | |

| Matrices over a principal ideal domain |  for some invertible Matrices P and Q for some invertible Matrices P and Q |

Smith normal form | The equivalence is the same as allowing invertible elementary row and column transformations |

| Finite-dimensional vector spaces over a field K | A and B are isomorphic as vector spaces |  , n a non-negative integer , n a non-negative integer |

Classical logic

- Negation normal form

- Conjunctive normal form

- Disjunctive normal form

- Algebraic normal form

- Prenex normal form

- Skolem normal form

Functional analysis

| Objects | A is equivalent to B if: | Normal form |

|---|---|---|

| Hilbert spaces | A and B are isometrically isomorphic as Hilbert spaces |  sequence spaces (up to exchanging the index set I with another index set of the same cardinality) sequence spaces (up to exchanging the index set I with another index set of the same cardinality) |

Commutative  -algebras with unit -algebras with unit |

A and B are isomorphic as  -algebras -algebras |

The algebra  of continuous functions on a compact Hausdorff space, up to homeomorphism of the base space. of continuous functions on a compact Hausdorff space, up to homeomorphism of the base space. |

Number theory

- canonical representation of a positive integer

- canonical form of a continued fraction

Algebra

| Objects | A is equivalent to B if: | Normal form |

|---|---|---|

| Finitely generated R-modules with R a principal ideal domain | A and B are isomorphic as R-modules | Primary decomposition (up to reordering) or invariant factor decomposition |

Geometry

- The equation of a line: Ax + By = C, with A2 + B2 = 1 and C ≥ 0

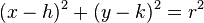

- The equation of a circle:

By contrast, there are alternative forms for writing equations. For example, the equation of a line may be written as a linear equation in point-slope and slope-intercept form.

Mathematical notation

Standard form is used by many mathematicians and scientists to write extremely large numbers in a more concise and understandable way.

Set theory

- Cantor normal form of an ordinal number

Game theory

- Normal form game

Proof theory

Rewriting systems

- In an abstract rewriting system a normal form is an irreducible object.

Lambda calculus

- Beta normal form if no beta reduction is possible; Lambda calculus is a particular case of an abstract rewriting system.

Dynamical systems

- Normal form of a bifurcation

Graph theory

Differential forms

Canonical differential forms include the canonical one-form and canonical symplectic form, important in the study of Hamiltonian mechanics and symplectic manifolds.

Computation

See also

- Canonical class

- Normalization (disambiguation)

- Standardization

References

- Shilov, Georgi E. (1977), Silverman, Richard A., ed., Linear Algebra, Dover, ISBN 0-486-63518-X.