Camera lucida

A camera lucida is an optical device used as a drawing aid by artists.

The camera lucida performs an optical superimposition of the subject being viewed upon the surface upon which the artist is drawing. The artist sees both scene and drawing surface simultaneously, as in a photographic double exposure. This allows the artist to duplicate key points of the scene on the drawing surface, thus aiding in the accurate rendering of perspective.

History

The camera lucida was patented in 1807 by William Hyde Wollaston. The basic optics were described 200 years earlier by Johannes Kepler in his Dioptrice (1611), but there is no evidence he or his contemporaries constructed a working camera lucida.[1] By the 19th century, Kepler’s description had totally fallen into oblivion, so Wollaston’s claim was never challenged. The term "camera lucida" (Latin "light room" as opposed to camera obscura "dark room") is Wollaston's. (cf. Edmund Hoppe, Geschichte der Optik, Leipzig 1926)

While on honeymoon in Italy in 1833, the photographic pioneer William Fox Talbot used a camera lucida as a sketching aid. He later recorded that it was a disappointment with his resulting efforts which encouraged him to seek a means to "cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably".

In 2001, artist David Hockney's book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters was met with controversy. His argument, known as the Hockney-Falco thesis, is that great artists of the past, such as Ingres, Van Eyck, and Caravaggio did not work freehand but were guided by optical devices, specifically an arrangement using a concave mirror to project real images. His evidence is based entirely on the characteristics of the paintings themselves.

The camera lucida is still available today through art-supply channels but is not well known or widely used.

Description

The name "camera lucida" (Latin for "light chamber") is obviously intended to recall the much older drawing aid, the camera obscura (Latin for "dark chamber"). There is no optical similarity between the devices. The camera lucida is a light, portable device that does not require special lighting conditions. No image is projected by the camera lucida.

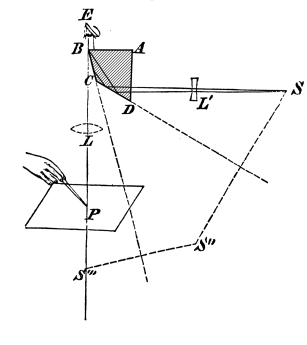

In the simplest form of camera lucida, the artist looks down at the drawing surface through a half-silvered mirror tilted at 45 degrees. This superimposes a direct view of the drawing surface beneath, and a reflected view of a scene horizontally in front of the artist. This design produces an inverted image which is right-left reversed when turned the right way up. Also, light is lost in the imperfect reflection. Wollaston's design used a prism with four optical faces to produce two successive reflections (see illustration), thus producing an image that is not inverted or reversed. Angles ABC and ADC are 67.5° and BCD is 135°. Hence, the reflections occur through total internal reflection so very little light is lost. It is not possible to see straight through the prism so it is necessary to look at the very edge to see the paper.[2] The instrument often includes a weak negative lens, creating a virtual image of the scene at about the same distance as the drawing surface, so that both can be viewed in good focus simultaneously.

If white paper is used with the camera lucida, the superimposition of the paper with the scene tends to wash out the scene, making it difficult to view. When working with a camera lucida it is often beneficial to use black paper and to draw with a white pencil.

The camera lucida that commercial comprehensive ("comp") layout artists used from the early 1950s to late 1980s used lenses positioned over a platform where the original reference material (like a photo) was placed. A bellows arrangement and two cranks allowed the artist to expand or reduce the size of the image. The artist could step up and place his or her head under a shade canopy to see the image. The image was projected upward onto a sheet of glass parallel to the floor, where the artist could place a translucent sheet of white layout paper on which to draw. This machine provided the artist a means of quickly and accurately drawing products and of using other photos in the composition.

Microscopy

As recently as a few decades ago the camera lucida was still a standard tool of microscopists. It is still a key tool in the field of palaeontology. Until very recently, photomicrographs were expensive to reproduce. Furthermore, in many cases, a clear illustration of the structure that the microscopist wished to document was much easier to produce by drawing than by micrography. Thus, most routine histological and microanatomical illustrations in textbooks and research papers were camera lucida drawings rather than photomicrographs. The camera lucida is still used as the most common method among neurobiologists for drawing brain structures, although it is recognised to have limitations. "For decades in cellular neuroscience, camera lucida hand drawings have constituted essential illustrations. (...) The limitations of camera lucida can be avoided by the procedure of digital reconstruction".[3] Of particular concern is distortion, and new digital methods are being introduced which can limit or remove this, "computerized techniques result in far fewer errors in data transcription and analysis than the camera lucida procedure".[4] It is also regularly used in biological taxonomy.

See also

- Camera obscura

- Claude glass, or black mirror

- Graphic telescope

- Pepper's ghost

References

- ↑ Hammond, John & Austin, Jill (1987). The camera lucida in art and science. Taylor & Francis. p. 16.

- ↑ Hockney, David (2006). Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500286388. quoting Woolaston, W.H. (1807). "Description of the camera lucida". A Journal of natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts.

- ↑ Mobilizing the base of neuroscience data: the case of neuronal morphologies, Giorgio A. Ascoli, Nature Reviews, Neuroscience, Vol. 7, April 2006, page 319

- ↑ Distortions induced in neuronal quantification by camera lucida analysis: Comparisons using a semi-automated data acquisition system, T.J. DeVoogd et al, Journal of Neuroscience Methods, Volume 3, Issue 3, February 1981, Pages 285–294

External links

- NeoLucida, a modern camera lucida

- Kenyon College Department of Physics on the Camera Lucida

- How to use a Camera Lucida

- Leon Camera Lucida