Calipers

A caliper (British spelling also calliper, or in plurale tantum sense a pair of calipers) is a device used to measure the distance between two opposite sides of an object. A caliper can be as simple as a compass with inward or outward-facing points. The tips of the caliper are adjusted to fit across the points to be measured, the caliper is then removed and the distance read by measuring between the tips with a measuring tool, such as a ruler.

It is used in many fields such as mechanical engineering, metalworking, forestry, woodworking, science and medicine.

Nomenclature variants

A plurale tantum sense of the word "calipers" coexists in natural usage with the regular noun sense of "caliper". That is, sometimes a caliper is treated cognitively like a pair of glasses or a pair of scissors, resulting in a phrase such as "hand me those calipers" or "those calipers are mine" in reference to one unit.

Also existing colloquially but not in formal usage is referring to a vernier caliper as a "vernier" or a "pair of verniers". In imprecise colloquial usage, some speakers extend this even to dial calipers, although they involve no vernier scale.

In machine-shop usage, the term "caliper" is often used in contradistinction to "micrometer", even though outside micrometers are technically a form of caliper. In this usage, "caliper" implies only the form factor of the vernier or dial caliper (or its digital counterpart).

History

The earliest caliper has been found in the Greek Giglio wreck near the Italian coast. The ship find dates to the 6th century BC. The wooden piece already featured a fixed and a movable jaw.[1][2] Although rare finds, caliper remained in use by the Greeks and Romans.[2][3]

A bronze caliper, dating from 9 AD, was used for minute measurements during the Chinese Xin dynasty. The caliper had an inscription stating that it was "made on a gui-you day at new moon of the first month of the first year of the Shijian guo period." The calipers included a "slot and pin" and "graduated in inches and tenths of an inch."[4][5]

The modern vernier caliper, reading to thousandths of an inch, was invented by American Joseph R. Brown in 1851. It was the first practical tool for exact measurements that could be sold at a price within the reach of ordinary machinists.[6]

Types

Inside caliper

The inside calipers are used to measure the internal size of an object.

- The upper caliper in the image (at the right) requires manual adjustment prior to fitting, fine setting of this caliper type is performed by tapping the caliper legs lightly on a handy surface until they will almost pass over the object. A light push against the resistance of the central pivot screw then spreads the legs to the correct dimension and provides the required, consistent feel that ensures a repeatable measurement.

- The lower caliper in the image has an adjusting screw that permits it to be carefully adjusted without removal of the tool from the workpiece.

Outside caliper

Outside calipers are used to measure the external size of an object.

The same observations and technique apply to this type of caliper, as for the above inside caliper. With some understanding of their limitations and usage these instruments can provide a high degree of accuracy and repeatability. They are especially useful when measuring over very large distances, consider if the calipers are used to measure a large diameter pipe. A vernier caliper does not have the depth capacity to straddle this large diameter while at the same time reach the outermost points of the pipe's diameter. They are made from high carbon steel.

Divider caliper

In the metalworking field, a divider caliper, popularly called a compass, is used in the process of marking out locations. The points are sharpened so that they act as scribers, one leg can then be placed in the dimple created by a center or prick punch and the other leg pivoted so that it scribes a line on the workpiece's surface, thus forming an arc or circle.

A divider caliper is also used to measure a distance between two points on a map. The two caliper's ends are brought to the two points whose distance is being measured. The caliper's opening is then either measured on a separate ruler and then converted to the actual distance, or it is measured directly on a scale drawn on the map. On a nautical chart the distance is often measured on the latitude scale appearing on the sides of the map: one minute of arc of latitude is approximately one nautical mile or 1852 metres.

Dividers are also used in the medical profession. An ECG (also EKG) caliper transfers distance on an electrocardiogram; in conjunction with the appropriate scale, the heart rate can be determined. A pocket caliper versions was invented by cardiologist Robert A. Mackin.[7]

Oddleg caliper

Oddleg calipers, Hermaphrodite calipers, or Oddleg jennys, as pictured on the left, are generally used to scribe a line a set distance from the edge of a workpiece. The bent leg is used to run along the workpiece edge while the scriber makes its mark at a predetermined distance, this ensures a line parallel to the edge.

In the diagram at left, the uppermost caliper has a slight shoulder in the bent leg allowing it to sit on the edge more securely, the lower caliper lacks this feature but has a renewable scriber that can be adjusted for wear, as well as being replaced when excessively worn.

Vernier caliper

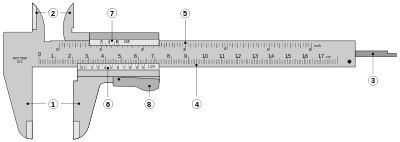

- Outside jaws: used to measure external diameter or width of an object

- Inside jaws: used to measure internal diameter of an object

- Depth probe: used to measure depths of an object or a hole

- Main scale: scale marked every mm

- Main scale: scale marked in inches and fractions

- Vernier scale gives interpolated measurements to 0.1 mm or better

- Vernier scale gives interpolated measurements in fractions of an inch

- Retainer: used to block movable part to allow the easy transferring of a measurement

The vernier, dial, and digital calipers give a direct reading of the distance measured with high accuracy and precision. They are functionally identical, with different ways of reading the result. These calipers comprise a calibrated scale with a fixed jaw, and another jaw, with a pointer, that slides along the scale. The distance between the jaws is then read in different ways for the three types.

The simplest method is to read the position of the pointer directly on the scale. When the pointer is between two markings, the user can mentally interpolate to improve the precision of the reading. This would be a simple calibrated caliper; but the addition of a vernier scale allows more accurate interpolation, and is the universal practice; this is the vernier caliper.

Vernier, dial, and digital calipers can measure internal dimensions (using the uppermost jaws in the picture at right), external dimensions using the pictured lower jaws, and in many cases depth by the use of a probe that is attached to the movable head and slides along the centre of the body. This probe is slender and can get into deep grooves that may prove difficult for other measuring tools.

The vernier scales may include metric measurements on the lower part of the scale and inch measurements on the upper, or vice versa, in countries that use inches. Vernier calipers commonly used in industry provide a precision to 0.01 mm (10 micrometres), or one thousandth of an inch. They are available in sizes that can measure up to 1,829 mm (72 in).[8]

Dial caliper

Instead of using a vernier mechanism, which requires some practice to use, the dial caliper reads the final fraction of a millimeter or inch on a simple dial.

In this instrument, a small, precise rack and pinion drives a pointer on a circular dial, allowing direct reading without the need to read a vernier scale. Typically, the pointer rotates once every inch, tenth of an inch, or 1 millimeter. This measurement must be added to the coarse whole inches or centimeters read from the slide. The dial is usually arranged to be rotatable beneath the pointer, allowing for "differential" measurements (the measuring of the difference in size between two objects, or the setting of the dial using a master object and subsequently being able to read directly the plus-or-minus variance in size of subsequent objects relative to the master object).

The slide of a dial caliper can usually be locked at a setting using a small lever or screw; this allows simple go/no-go checks of part sizes.

Digital caliper

A refinement now popular is the replacement of the analog dial with an electronic digital display on which the reading is displayed as a single value. Rather than a rack and pinion, they have a linear encoder. Some digital calipers can be switched between centimeters or millimeters, and inches. All provide for zeroing the display at any point along the slide, allowing the same sort of differential measurements as with the dial caliper. Digital calipers may contain some sort of "reading hold" feature, allowing the reading of dimensions even in awkward locations where the display cannot be seen. Ordinary 6-in/150-mm digital calipers are made of stainless steel, have a rated accuracy of 0.001 in (0.02mm) and resolution of 0.0005 in (0.01 mm). [9] The same technology is used to make longer 8-in and 12-in calipers; the accuracy for bigger measurements declines to 0.001 in (0.03 mm) for 100–200 mm and 0.0015 in (0.04 mm) for 200–300 mm. [10]

Many Chinese-made digital calipers are inexpensive and perform reasonably well. One point worth noting is battery current when they are turned off. Many calipers do not stop drawing power when the switch is in the off position; they shut down the display but continue drawing nearly as much current. The current may be as much as 20 microamperes,[11] which is much higher than many established brands. Sometimes calipers may not work properly when the battery voltage has dropped relatively little; silver cells, preferably selected from a datasheet to have a constant voltage for most of their life, may give a much longer usable life than alkaline button cells (e.g., SR44 instead of LR44).[11][12]

Increasingly, digital calipers offer a serial data output to allow them to be interfaced with a dedicated recorder or a personal computer. The digital interface significantly decreases the time to make and record a series of measurements, and it also improves the reliability of the records. A suitable device to convert the serial data output to common computer interfaces such as RS-232, Universal Serial Bus, or wireless can be built or purchased. With such a converter, measurements can be directly entered into a spreadsheet, a statistical process control program, or similar software.

The serial digital output varies among manufacturers. Common options are

- Mitutoyo's Digimatic interface. This is the dominant name brand interface. Format is 52 bits arranged as 13 nibbles.[13][14][15][16]

- Sylvac interface. This is the common protocol for inexpensive, non-name brand, calipers. Format is 24 bit 90 kHz synchronous.[17][18]

- Starrett[19]

- Brown & Sharpe[19]

- Federal

- Mahr (appears to offer Digimatic, RS232, and USB)

- Tesa[19]

- Aldi. Format is 7 BCD digits.[18]

Like dial calipers, the slide of a digital caliper can usually be locked using a lever or thumb-screw.

Some digital calipers contain a capacitive linear encoder. A pattern of bars is etched directly on the printed circuit board in the slider. Under the scale of the caliper another printed circuit board also contains an etched pattern of lines. The combination of these printed circuit boards forms two variable capacitors. The two capacitances are out of phase. As the slider moves the capacitance changes in a linear fashion and in a repeating pattern. The circuitry built into the slider counts the bars as the slider moves and does a linear interpolation based on the magnitudes of the capacitors to find the precise position of the slider. Other digital calipers contain an inductive linear encoder, which allows robust performance in the presence of contamination such as coolants.[20] Magnetic linear encoders are used in yet other digital calipers.

Micrometer caliper

A caliper using a calibrated screw for measurement, rather than a slide, is called a micrometer caliper or, more often, simply a micrometer. (Sometimes the term caliper, referring to any other type in this article, is held in contradistinction to micrometer.)

Comparison

Each of the above types of calipers have their relative merits and faults.

Vernier calipers are rugged and have long lasting accuracy, are coolant proof, are not affected by magnetic fields, and are largely shock proof. They may have both centimeter and inch scales. However, vernier calipers require good eyesight or a magnifying glass to read and can be difficult to read from a distance or from awkward angles. It is relatively easy to misread the last digit. In production environments, reading vernier calipers all day long is error-prone and is annoying to the workers.

Dial calipers are comparatively easy to read, especially when seeking exact center by rocking and observing the needle movement. They can be set to 0 at any point for comparisons. They are usually fairly susceptible to shock damage. They are also very prone to getting dirt in the gears, which can cause accuracy problems.

Digital calipers switch easily between centimeter and inch systems.They can be set to 0 easily at any point with full count in either direction, and can take measurements even if the display is completely hidden, either by using a "hold" key, or by zeroing the display and closing the jaws, showing the correct measurement, but negative. They can be mechanically and electronically fragile. Most also require batteries, and do not resist coolant well. They are also only moderately shockproof, and can be vulnerable to dirt.

Calipers may read to a resolution of 0.01 mm or 0.0005 in, but accuracy may not be better than about ±0.02 mm or 0.001 in for 150 mm (6 in) calipers, and worse for longer ones.[21]

Use

A caliper must be properly applied against the part in order to take the desired measurement. For example, when measuring the thickness of a plate a vernier caliper must be held at right angles to the piece. Some practice may be needed to measure round or irregular objects correctly.

Accuracy of measurement when using a caliper is highly dependent on the skill of the operator. Regardless of type, a caliper's jaws must be forced into contact with the part being measured. As both part and caliper are always to some extent elastic, the amount of force used affects the indication. A consistent, firm touch is correct. Too much force results in an underindication as part and tool distort; too little force gives insufficient contact and an overindication. This is a greater problem with a caliper incorporating a wheel, which lends mechanical advantage. This is especially the case with digital calipers, calipers out of adjustment, or calipers with a poor quality beam.

Simple calipers are uncalibrated; the measurement taken must be compared against a scale. Whether the scale is part of the caliper or not, all analog calipers—verniers and dials—require good eyesight in order to achieve the highest precision. Digital calipers have the advantage in this area.

Calibrated calipers may be mishandled, leading to loss of zero. When a calipers' jaws are fully closed, it should of course indicate zero. If it does not, it must be recalibrated or repaired. It might seem that a vernier caliper cannot get out of calibration but a drop or knock can be enough. Digital calipers have zero set buttons.

Vernier, dial and digital calipers can be used with accessories that extend their usefulness. Examples are a base that extends their usefulness as a depth gauge and a jaw attachment that allows measuring the center distance between holes. Since the 1970s a clever modification of the moveable jaw on the back side of any caliper allows for step or depth measurements in addition to external caliper measurements, in similar fashion to a universal micrometer (e.g., Starrett Mul-T-Anvil or Mitutoyo Uni-Mike).

Zero error

The method to use a vernier scale or caliper with zero error is to use the formula 'actual reading = main scale + vernier scale − (zero error)'. Zero error may arise due to knocks that cause the calibration at the 0.00 mm when the jaws are perfectly closed or just touching each other.

See also

- Dial indicator

- Cruising rod

- Lens clock

References

- ↑ Mensun Bound: The Giglio wreck: a wreck of the Archaic period (c. 600 BC) off the Tuscany island of Giglio, Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology, Athens 1991, pp. 27 and 31 (Fig. 65)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Roger B. Ulrich: Roman woodworking, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., 2007, ISBN 0-300-10341-7, p.52f.

- ↑ "hand tool." Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD. [Accessed July 29, 2008]

- ↑ Colin A. Ronan; Joseph Needham (24 June 1994). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China: 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-521-32995-8. "adjustable outside caliper gauge... self-dated at AD 9". An abridged version.

- ↑ http://history.cultural-china.com/en/56H2758H7991.html

- ↑ Joseph Wickham Roe, English and American tool builders (1916) p. 203

- ↑ http://www.mackinmfg.com/ shows a picture of the calipers but does not support the RAM claim.

- ↑ http://www.starrett.com/download/246_p108_114.pdf

- ↑ 6 in Digital Caliper

- ↑ http://www.msi-viking.com/digital_caliper/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Caliper Battery Life

- ↑ Buying Button Cells for Digital Calipers

- ↑ Mitutoyo 1715, page 22.

- ↑ Mitutoyo E4174-524, page 33.

- ↑ Don Lancaster, Tech Musings 145

- ↑ AllAboutCircuits

- ↑ Shumatech

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Yadro

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Don Lancaster, Tech Musings 142, page 142.3

- ↑ http://www.mitutoyo.com/pdf/ABS1813-293.pdf

- ↑ Accuracy of calipers

External links

-

Media related to Calipers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Calipers at Wikimedia Commons - Open Source Physics Vernier calipers Computer Model

- Animated Vernier calipers

- RS-232 Interface Design Details For Digital Caliper

- How Digital Calipers work

- How Digital Calipers work at YADRO

- Caliper interface with lcd and led

- Flash Simulator of Vernier Callipers based on photographs of an actual device

- Adobe AIR application screen ruler based on a Vernier caliper

- Simulator of use and interpretation: Vernier caliper in millimeter, resolution of 0.05 mm

- Simulator of use and interpretation: Dial caliper in inch, resolution of 1/64in

- Simulator of use and interpretation: Digital caliper in inch, resolution of 0.0005 in

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||