Burnt Fen

| Burnt Fen | |

The Engine Drain where it meets the River Lark at Lark Engine House |

|

Burnt Fen | |

| OS grid reference | TL605875 |

|---|---|

| Shire county | Cambridgeshire |

| Region | East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| EU Parliament | East of England |

| |

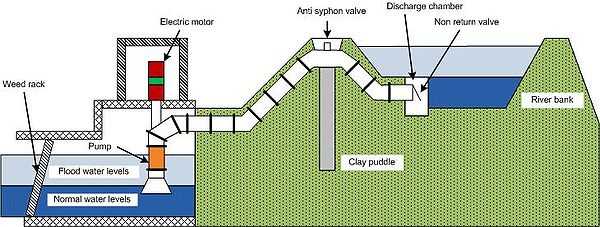

Burnt Fen is an area of low-lying land crossed by the A1101 road between Littleport in Cambridgeshire and Mildenhall in Suffolk, England. It is surrounded on three sides by rivers, and consists of prime agricultural land, with sparse settlement. It is dependent on pumped drainage to prevent it from flooding.

Between 1759 and 1962 the area was managed by the Commissioners of the Burnt Fen First Drainage District, who were then replaced by the Burnt Fen Internal Drainage Board, when the area of responsibility was expanded. Funding for the drainage works is collected by a system of rates, paid by those whose property would be threatened by flooding without the works.

Location

Burnt Fen is located near the eastern borders of Cambridgeshire, although parts of it are also located in Suffolk and Norfolk. It is an area of prime agricultural land, which is mostly below sea level, and all of it is below the normal flood levels of the rivers which surround it on three sides. These comprise the River Great Ouse (or Ten Mile River) on the north western edge, the River Little Ouse (or Brandon Creek) on the north eastern edge and the River Lark on the south western edge. The area is crossed by the A1101 Littleport to Mildenhall road, which runs broadly north west to south east, and the Ely to Norwich Railway, which runs from east to west. There are four hamlets within this area, Little Ouse, Shippea Hill, Sedge Fen and Mile End.[1] Shippea Hill railway station was called Burnt Fen between 1885 and 1904.

Because of the low-lying nature of the terrain, the area is entirely dependent on pumped drainage to prevent it from being flooded. The Commissioners of the Burnt Fen First District were formed by Act of Parliament in 1759, and managed the drainage ditches and pumping stations until 1962, when the Burnt Fen Drainage District was expanded a little, and a new Internal Drainage Board was constituted to manage the area. They are responsible for 17,140 acres (6,940 ha) of land, which includes 42.3 miles (68.1 km) of drainage ditches and two pumping stations, one on the River Lark, and the other on the Great Ouse. Water flows along the drainage channels by gravity, and is then lifted by up to 16 feet (4.9 m) to enter the high level rivers.[1]

The name "Burnt Fen" is believed to originate from the practice of leveling the land, which has been carried out since the mid 17th century. Large tufts of rushes, which made the land surface rough, were cut and dried. Once dried, they could be burnt, and the ashes used as fertiliser.[2] This practice, known as paring and burning, was used widely in the Fens, and was advocated by Walter Blith in his book The English Improver Improved, published in 1652. He suggested that it should be used on the lowest levels of fen land which had been 'long drowned', and recorded details of the practical application of the process to an area of 28,000 acres (110 km2) in the Bedford Level.[3]

Archaeology

The area shows a remarkable amount of archaeological findings of the Mesolithic period. One of the largest hoards of Bronze-Age artifacts ever unearthed in western Europe was found near Isleham. Many of the 6,000 pieces are on show at the Moyses Hall Museum, located in Bury St Edmunds.[4]

History

Burnt Fen is part of the South Level of the Fens, and as such was judged to have been drained satisfactorily as a result of the work of the Dutch drainage engineer Cornelius Vermuyden and his adventurers in 1652. The courses of a number of rivers had been altered to improve drainage and reclaim land for agriculture, and a thanksgiving service was held in Ely Cathedral to celebrate the event. Burnt Fen was a low-lying region surrounded on three sides by the River Great Ouse, the River Little Ouse, and the River Lark.[5]

From the beginning, there were tensions between those who wanted to use the rivers for navigation and those who wanted to use them for drainage, to the extent that when Denver Sluice was demolished by an extremely high tide in 1713, the towns of Cambridge and Thetford petitioned against its reconstruction. However, a more serious problem for the Burnt Fen area was the steady shrinkage of the land surface as the water was removed from the peat soils, and the blowing away of the light soil as it dried out. Water could no longer flow by gravity from the land into the rivers. Although the Bedford Level Corporation was responsible for the main rivers in the region, they did not have control of the smaller tributaries. Landowners could and did build windmills to act as drainage engines, but there was no overall policy, with the result that there were legal disputes, with one landowner complaining that a neighbour's drainage mill resulted in flooding of surrounding properties.[5]

The First Commissioners

Against this background, a private Act of Parliament was obtained in 1759, which created two drainage districts. Each had its own set of Commissioners, and the boards were called the Burnt Fen First District and the Burnt Fen Second District. The area controlled by the First District broadly covers the area known as Burnt Fen today, while the Second District is known as Lakenheath Little Fen. Besides notables such as the Lord Bishop of Ely and others, every person who owned 300 acres (120 ha) of "taxable land" was a commissioner, and people who owned over 6 acres (2.4 ha) of land could vote annually for several elected commissioners. "Taxable land" consisted of any land that might be affected by flooding, and would therefore benefit from drainage measures.[5]

The Commissioners met for the first time on 6 June 1760, and planned the take-over of all of the drainage mills in the region, the construction of new ones, and the digging of the main drainage channels which would feed surface water to the mills and into the rivers. To finance these operations, there were empowered to borrow money, and to charge a drainage rate of 1 shilling (5p) per acre, rising to 1/6d (7.5p) after seven years. The costs of carrying out such work were grossly optimistic, and the commissioners were soon in financial difficulties.[5] Despite this, and heavy flooding in the winter of 1761/2, which resulted in no taxes being collected, the Commissioners owned eight mills by 1774, each of which used a scoop wheel to lift water into the rivers. The costs of maintenance and repair of the mills were high, not helped by the Naval shipbuilding programme driving up the cost of oak.[6]

Part of the defence of the area involved the construction of a cross bank across its south eastern edge, to prevent flood water from the Lakenheath Little Fen reaching the Burnt Fen. The costs of building this were large, as were the costs of maintaining the river banks, and so in 1772, a second Act of Parliament was obtained, authorising the raising of the drainage rate to 2 shillings (10p) per acre for ten years, and the imposing of penalties for late payment of the rates. A third Act was obtained in 1796, to raise the rates to 3/6 (17.5p) per acre, and kept them solvent for another eleven years. By 1807, they had borrowed £11,500 to finance the work, with little prospect of being able to pay it back. A fourth Act of Parliament increased the rates again, and changed the constitution of the Commissioners.[7]

Progress was not always smooth. Young, writing in 1794, recorded that there had been serious breaches of the banks in 1777, which had resulted in the ruin of many of the proprietors. However, a machine called the bear had been used to dredge the bottoms of the rivers, and in 1782, servants of the former proprietors had bought plots of land at reduced prices, which had proved to be profitable. He noted that one estate, bought for £200, could be sold for £2,000, following the completion of better banks and mills.[8]

Mechanisation

Wind engines had the inherent design fault that they would only work when the wind blew, and could therefore be unusable when they were most needed. The Commissioners therefore turned their attention to mechanising the pumping mills, and employed Mr. W. C. Mylne to advise them on the relative benefits of steam and gas engines in 1829. His report recommended the use of steam engines, and so a 40 horsepower (30 kW) engine was ordered from Boulton Watt and Co., which would drive two scoop wheels. The engine cost £1,184, and the engine house another £835. It was installed where the Whitehouse Drain met the River Little Ouse (otherwise known as Brandon Creek), and was commissioned in 1832, when it became known as the Brandon Engine. There were initial teething problems, which resulted in one of the scoop wheels being removed, repairs to the boiler, and a second boiler being installed, but once these problems had been sorted out, it became obvious that the new system was an efficient way to drain the Fens.[9]

The Brandon Engine served the north part of the Fen, and the Commissioners decided that a similar engine should serve the south of the District. Tenders were invited, and Boulton Watt and Co. again supplied a 40 horsepower (30 kW) engine, this time with three boilers. The chosen location on the River Lark required the construction of the Engine Drain. Purchase of the land for the new drain was protracted, but once obtained, the engine was commissioned in 1842 and there were no significant teething problems. The Brandon Engine was thought to be worn out by 1848, and a new Cornish type boiler was fitted. Experiments were carried out to try to improve the lift and efficiency of the scoop wheels, as the land levels, and consequently the depth of the drains, continued to sink. Larger scoop wheels were fitted to the Brandon Engine in 1860, and to the Lark Engine shortly afterwards.[9]

The financial standing of the Drainage District had steadily improved since the 1807 Act, and they were repaying the money borrowed in earlier years. A Fifth Burn Fen Act was obtained in 1823, which recognised the damage done to river banks by horses and commercial traffic using them, and made provision for such use to be charged. The burden of repair costs to river banks was further lightened by an annual contribution from the Bedford Level Corporation, and also from the Turnpike Commissioners, who had built a road close to the course of the River Great Ouse on the north western edge of the Fen, although this latter sum proved difficult to obtain at times.[9]

Under the Acts of Parliament obtained in 1759, 1773, 1797, and 1807, two drainage districts had been set up, called the Burnt Fen First District and the Burnt Fen Second District. Re-organisation in 1879 resulted in the First District being renamed the Burnt Fen District, while the Second District became the Mildenhall District.[10]

The Steam Age

By 1882, the scoop wheels had reached the practical limits of improvement, and the Commissioners asked George Carmichael to act as a consulting engineer, and advise on how centrifugal pumps could be utilised. Carmichael recommended a new engine and pump, and an 80 horsepower (60 kW) engine was obtained from Hathorn Davey and Co., which would drive a horizontally mounted centrifugal pump of 6.5 feet (2.0 m) diameter. Completion of the Lark Engine installation was delayed by failure to achieve the quoted output, and by flood levels affecting the construction of the outfall tunnel, but the problems were resolved by November 1883, and the Commissioners were able to delay taking a decision on the Brandon Engine because of the efficiency of the new engine.[11]

When they turned their attention to the Brandon Engine in 1890, it was in a worse state than expected. The drains in the northern and southern sections of the Burnt Fen were by then interconnected, so that either engine could pump the whole area in an emergency, and plans for a new Brandon Engine were made immediately. Following the success of the Lark Engine, Hathorn, Davey and Co. were contacted, and supplied a pump set capable of pumping 75 tons per minute, which was operational by October 1892. Although the pump worked well, there were protracted arguments over a set of spanners which had been invoiced as an "extra".[11]

The Commissioners had employed teams of gaulters throughout the 19th and early 20th century, who got their name from the use of an impervious type of clay called gault, which was obtained from Roswell Pits at Ely, and used to repair the banks of the rivers and the cross dyke. The teams consisted of three men, who managed a train of five boats between them, each capable of holding 8 tons of gault. The boats were owned by the Commissioners, but the men were responsible for the provision of a horse, shovels and barrows. In 1886, new terms of employment were negotiated by the Commissioners, as they felt that the wages earned by the men were excessive. In 1920, the Ouse Drainage Board was established, and responsibility for the maintenance of the river banks passed to them, so the Commissioners laid off the men and sold the boats.[12]

Modernisation

With the land surfaces still sinking, the Commissioners looked at ways to improve the discharge of the engines in 1919, but did not take any immediate action. Instead, they considered the replacement of the steam engines by oil engines, and in 1924 asked Blackstone and Company Limited to supply two 250 horsepower (190 kW) oil engines, each with a 42 inches (110 cm) Gwynne rotary pump, capable of pumping 150 tons per minute. The engines were to be erected alongside the existing engines, which could then still be used as a backup in an emergency. The new Brandon engine was installed by Autumn 1925, but the completion of the Lark engine was celebrated in a much grander style, with all taxpayers from the district being invited to the opening, which was followed by a lunch party.[13]

1926 saw further improvements, when the traditional use of spades and barrows to maintain the drains was superseded by a petrol/paraffin dragline excavator, obtained from Priestman Bros. Limited. The Brandon steam engine did not last long as a standby as it was de-commissioned in April 1927 and finally sold for scrap for £25 in 1933. The Lark engine fared better, and although little used, was maintained in working order until 1945. Further consideration was given to upgrading the engines in 1939, but the start of the Second World War delayed implementation. Approval was eventually obtained to install a Crossley 300 brake horsepower (220 kW) engine driving a 42 inches (110 cm) Gwynne rotary pump, capable of pumping 150 tons per minute in 1941, but it was January 1945 before work was completed. The Lark steam engine was sold for scrap in July, and the engine house converted into a workshop.[13]

The Brandon site was finally abandoned in the 1950s. The White House drain, which supplied it, had become steadily deeper as the land surface had sunk, and the soil through which it ran was unstable, requiring regular maintenance to prevent slippage. The pumping station was effectively on top of a hill, rather than being at the lowest part of the Fen, and so a decision was taken to construct a new pumping station at Whitehall on the River Great Ouse, which required the construction of 1.25 miles (2 km) of main pumping drain, to connect it to the existing drains. Two 210 brake horsepower (160 kW) electric motors with vertical spindle axial flow pumps were supplied by W. H. Allen Sons and Company Ltd, and the station was opened on 10 September 1958.[13]

Expansion

In 1959, the Commissioners looked into the drainage of several areas on the fringe of Burnt Fen, as a result of requests by landowners in Sedge Fen. A report suggested that the best solution would be the incorporation of those areas into an Internal Drainage Board, and the Commissioners therefore applied to the River Board to enlarge their District by the addition of 2,059 acres (833 ha) which included parts of Sedge Fen, Decoy Fen and Redmere. The expansion was ratified by the Great Ouse River Board (Burnt Fen Internal Drainage District) Order, which was passed in 1962. It revoked all of the Burnt Fen Acts, and after 203 years, the Commissioners ceased to exist, being replaced by an elected board of 20 members.[14]

The Lark Engine pumping station was upgraded again in 1974. The Blackstone engine was retired but kept intact as part of the history of the district, the Crossley engine became the standby, and the Crossley enginehouse was extended to allow the installation of a 230 brake horsepower (170 kW) Dorman diesel engine, which drives a 33-inch (84 cm) Allen Gwynne vertical spindle pump. The work included the provision of a wooden plaque, showing all of the engines which had been installed since the opening of the station in 1842, which was unveiled by Mrs F. G. Starling at the formal opening held on 25 May 1976. Further improvements followed, when negotiations with British Rail resulted in the skew bridge, which carried the Ely to Norwich line over the main drain being demolished and replaced by a culvert. This action allowed the main pumping drain to the Lark Engine to be made deeper and wider, improving flows between the two halves of Burnt Fen.[14]

Despite all the changes, the Lark Engine house still carries the inscription penned in 1842 by William Harrison, the Superintendent of the Works between 1831 and 1871.[9]

- In fitness for the urgent hour,

- Unlimited, untiring power,

- Precision, promptitude, command,

- The infant's will, the giant's hand,

- Steam, mighty steam, ascends the throne,

- And reigns lord paramount alone.

Bibliography

- Beckett, John (1983). The Urgent Hour. Ely Local History Publication Board. ISBN 978-0-904463-88-0.

- Blair, Andrew Hunter (2006). The River Great Ouse and tributaries. Imray Norie Laurie and Wilson. ISBN 978-0-85288-943-5.

- Darby, H C (1956). The Draining of the Fens. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-40298-0.

- Hinde, K S G (2006). Fenland Pumping Engines. Landmark Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84306-188-5.

- Young, A (1794). Agriculture of the County of Suffolk.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Burnt Fen Internal Drainage Board: Conservation, accessed 22 June 2009

- ↑ Beck Row Parish Council, History of Burnt Fen, accessed 11 July 2009

- ↑ Darby 1956, pp. 83-84.

- ↑ Blair 2006, p. 85

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Beckett 1983, pp. 7–9

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 11–17

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 18–20

- ↑ Young 1794, pp. 31-32 quoted in Darby 1956, pp. 166-167

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Beckett & 1983 , 21-26

- ↑ Hinde 2006, p. 108.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Beckett 1983, pp. 27–31

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 32–35

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Beckett 1983, pp. 36–43

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Beckett 1983, pp. 44–48

External links

- British History online The Isle of Ely

- Archaeology of Cambridgeshire