Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Unité–Progrès–Justice" (French) "Unity–Progress–Justice" |

||||||

| Anthem: Une Seule Nuit / Ditanyè (French) One Single Night / Hymn of Victory |

||||||

Location of Burkina Faso (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Ouagadougou 12°20′N 1°40′W / 12.333°N 1.667°W | |||||

| Official languages | French | |||||

| Recognised regional languages | ||||||

| Ethnic groups (1995) | ||||||

| Demonym |

|

|||||

| Government | Semi-presidential republic | |||||

| - | President | Blaise Compaoré | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Luc-Adolphe Tiao | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from France | 5 August 1960 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 274,200 km2 (74th) 105,869 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.146% | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2010 estimate | 15,730,977[1] (64th) | ||||

| - | 2006 census | 14,017,262 | ||||

| - | Density | 57.4/km2 (145th) 148.9/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $24.293 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,399[2] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $10.464 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $602[2] | ||||

| Gini (2007) | 39.5[3] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2007) | low · 177th |

|||||

| Currency | West African CFA franc[4] (XOF) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC+0) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +226 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | BF | |||||

| Internet TLD | .bf | |||||

| The data here is an estimation for the year 2005 produced by the International Monetary Fund in April 2005. | ||||||

Burkina Faso (![]() i/bərˌkiːnə ˈfɑːsoʊ/ bər-KEE-nə FAH-soh; French: [buʁkina faso]), also known by its short-form name Burkina, is a landlocked country in West Africa around 274,200 square kilometres (105,900 sq mi) in size. It is surrounded by six countries: Mali to the north; Niger to the east; Benin to the southeast; Togo and Ghana to the south; and Ivory Coast to the southwest. Its capital is Ouagadougou. In 2010, its population was estimated at just under 15.75 million.[1]

i/bərˌkiːnə ˈfɑːsoʊ/ bər-KEE-nə FAH-soh; French: [buʁkina faso]), also known by its short-form name Burkina, is a landlocked country in West Africa around 274,200 square kilometres (105,900 sq mi) in size. It is surrounded by six countries: Mali to the north; Niger to the east; Benin to the southeast; Togo and Ghana to the south; and Ivory Coast to the southwest. Its capital is Ouagadougou. In 2010, its population was estimated at just under 15.75 million.[1]

Formerly called the Republic of Upper Volta, the country was renamed "Burkina Faso" on 4 August 1984 by then-President Thomas Sankara, using a word from each of the country's two major native languages, Mòoré and Dioula. Figuratively, Burkina, from Mòoré, may be translated as "men of integrity", while Faso means "fatherland" in Dioula. "Burkina Faso" is understood as "Land of upright people" or "Land of honest people". Residents of Burkina Faso are known as Burkinabè (/bərˈkiːnəbeɪ/ bər-KEE-nə-bay). French is an official language of government and business in the country.

Between 14,000 and 5000 BC, Burkina Faso was populated by hunter-gatherers in the country's northwestern region. Farm settlements appeared between 3600 and 2600 BC.[citation needed] What is now central Burkina Faso was principally composed of Mossi kingdoms. In 1896 France established a protectorate over the kingdoms in this territory.

After gaining independence from France in 1960, the country underwent many governmental changes. Today it is a semi-presidential republic. The president is Blaise Compaoré. Burkina Faso is a member of the African Union, Community of Sahel-Saharan States, La Francophonie, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and Economic Community of West African States.

History

Early history

The northwestern part of today's Burkina Faso was populated by hunter-gatherers between 14,000 and 5000 BC. Their tools, including scrapers, chisels and arrowheads, were discovered in 1973 through archeological excavations. This was the basis of knowledge for much about the ancient indigenous peoples. Agricultural settlements were established between 3600 and 2600 BC. The people began using iron, ceramics and polished stone between 1500 and 1000 BC. By this time, they had developed religion, as shown by ritual burial remains.

The Dogon lived in Burkina Faso's north and northwest regions until sometime in the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, when they left for the cliffs of Bandiagara. The ruins of high walls built by an unknown culture remain in southwest Burkina Faso. Loropeni is a pre-European stone ruin which was linked to the gold trade. As more has been learned about it through excavations and studies, in 2009 it was designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, the first in Burkina Faso.

The central part of Burkina Faso included a number of Mossi kingdoms, the most powerful of which were Wagadogo (Ouagadougou) and Yatenga. Scholars believe these kingdoms probably emerged in the early sixteenth century. Their origins are obscured by a legend featuring a heterogeneous set of warrior figures.[5]

From colony to independence

At the time of European colonization efforts in the late nineteenth century, people in the Mossi kingdoms lived primarily in villages developed from kinship: based on clans and extended relations among tribal bands. They cultivated a variety of food crops to support themselves, as well as relying on fishing and hunting, and making use of domesticated animals such as goats. Like other West Africans, after centuries of trade with Europeans, including products imported from the Americas, they had absorbed certain new foods into their cuisine, as well as made use of European cloth, tool, and other items after centuries of trade between the continents. Their crops and products also entered other markets.

In the late nineteenth century, after a decade of intense rivalry and competition between the Great Britain and France, waged through treaty-making expeditions under military or civilian explorers, the Mossi kingdom of Ouagadougou was defeated by French colonial forces. In 1896 it became a French protectorate. The eastern and western regions, where a standoff against the forces of the powerful ruler Samori Ture complicated the situation, came under French occupation in 1897. By 1898, the majority of the territory corresponding to Burkina Faso today was nominally conquered; however, French control of many parts remained uncertain.

The French and British convention of 14 June 1898 ended the scramble between the two colonial powers and drew the borders between the countries' colonies. On the French side, a war of conquest against local communities and political powers continued for about five years. In 1904, the largely pacified territories of the Volta basin were integrated into the Upper Senegal and Niger colony of French West Africa as part of the reorganization of the French West African colonial empire. The colony had its capital in Bamako.

The French imposed their own language as the official one for colonial administration, and generally appointed French colonists or nationals to prominent positions. It did start some schools and selected top students for additional education in France.

Draftees from the territory participated in the European fronts of World War I in the battalions of the Senegalese Rifles. Between 1915 and 1916, the districts in the western part of what is now Burkina Faso and the bordering eastern fringe of Mali became the stage of one of the most important armed oppositions to colonial government, known as the Volta-Bani War.[6] The French government finally suppressed the movement, but only after suffering defeats. It also had to organize its largest expeditionary force of its colonial history up to that point to send into the country to suppress the insurrection. Armed opposition also wracked the Sahelian north when the Tuareg and allied groups of the Dori region ended their truce with the government.

French Upper Volta was established on 1 March 1919. The French feared a recurrence of armed uprising and had related economic considerations. To bolster its administration, the colonial government separated the present territory of Burkina Faso from Upper Senegal and Niger.

The new colony was named Haute Volta, and François Charles Alexis Édouard Hesling became its first governor. Hesling initiated an ambitious road-making program to improve infrastructure and promoted the growth of cotton for export. The cotton policy – based on coercion – failed, and revenue generated by the colony stagnated. The colony was dismantled on 5 September 1932, being split between the French colonies of Côte d'Ivoire, French Sudan and Niger. Côte d'Ivoire received the largest share, which contained most of the population as well as the cities of Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso.

France reversed this change during the period of intense anti-colonial agitation that followed the end of World War II. On 4 September 1947, it revived the colony of Upper Volta, with its previous boundaries, as a part of the French Union. The French designated its colonies as departments of the metropole France on the European continent.

On 11 December 1958 the colony achieved self-government as the Republic of Upper Volta; it joined the Franco-African Community. A revision in the organization of French Overseas Territories had begun with the passage of the Basic Law (Loi Cadre) of 23 July 1956. This act was followed by reorganizational measures approved by the French parliament early in 1957 to ensure a large degree of self-government for individual territories. Upper Volta became an autonomous republic in the French community on 11 December 1958. Full independence from France was received in 1960.[7]

Upper Volta

The Republic of Upper Volta (French: République de Haute-Volta) was established on 11 December 1958 as a self-governing colony within the French Community. The name Upper Volta related to the nation's location along the upper reaches of the Volta River. The river's three tributaries are called the Black, White and Red Volta. These are expressed in the three colors of the national flag.

Before attaining autonomy, it had been French Upper Volta and part of the French Union. On 5 August 1960, it attained full independence from France. The first president, Maurice Yaméogo, was the leader of the Voltaic Democratic Union (UDV). The 1960 constitution provided for election by universal suffrage of a president and a national assembly for five-year terms. Soon after coming to power, Yaméogo banned all political parties other than the UDV. The government lasted until 1966. After much unrest, including mass demonstrations and strikes by students, labor unions, and civil servants, the military intervened.

The military coup d'état deposed Yaméogo, suspended the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and placed Lt. Col. Sangoulé Lamizana at the head of a government of senior army officers. The army remained in power for four years. On 14 June 1970, the Voltans ratified a new constitution that established a four-year transition period toward complete civilian rule. Lamizana remained in power throughout the 1970s as president of military or mixed civil-military governments. After conflict over the 1970 constitution, a new constitution was written and approved in 1977. Lamizana was reelected by open elections in 1978.

Lamizana's government faced problems with the country's traditionally powerful trade unions, and on 25 November 1980, Col. Saye Zerbo overthrew President Lamizana in a bloodless coup. Colonel Zerbo established the Military Committee of Recovery for National Progress as the supreme governmental authority, thus eradicating the 1977 constitution.

Colonel Zerbo also encountered resistance from trade unions and was overthrown two years later, on 7 November 1982, by Maj. Dr. Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo and the Council of Popular Salvation (CSP). The CSP continued to ban political parties and organizations, yet promised a transition to civilian rule and a new constitution.

Factional infighting developed between moderates in the CSP and the radicals, led by Capt. Thomas Sankara, who was appointed prime minister in January 1983. The internal political struggle and Sankara's leftist rhetoric led to his arrest and subsequent efforts to bring about his release, directed by Capt. Blaise Compaoré. This release effort resulted in yet another military coup d'état on 4 August 1983.

After the coup, Sankara formed the National Council for the Revolution (CNR), with himself as president. Sankara also established Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) to "mobilize the masses" and implement the CNR's revolutionary programs. The CNR, whose exact membership remained secret until the end, contained two small intellectual Marxist-Leninist groups. Sankara, Compaore, Capt. Henri Zongo, and Maj. Jean-Baptiste Lingani—all leftist military officers—dominated the regime.

On 4 August 1984,[7] as a final result of President Sankara's activities, the country's name was eventually changed from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso. The name combines a word of Mossi origin with a word of Mande origin, in order to be inclusive of the different ethnic groups in country, and translates to "land of honest people".[8][9]

Burkina Faso

On 15 October 1987, Sankara was killed by an armed gang with twelve other officials in a coup d'état organized by his former colleague and current president, Blaise Compaoré. Deterioration in relations with neighbouring countries was one of the reasons given, with Compaoré stating that Sankara jeopardised foreign relations with former colonial power France and neighbouring Côte d'Ivoire. Prince Johnson, a former Liberian warlord allied to Charles Taylor, told Liberia's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that it was engineered by Charles Taylor. After the coup and although Sankara was known to be dead, some CDRs mounted an armed resistance to the army for several days.

Sankara's body was dismembered and he was quickly buried in an unmarked grave, while his widow and two children fled the country. Compaoré immediately reversed the nationalizations, overturned nearly all of Sankara's policies, returned the country back under the IMF fold, and ultimately spurned most of Sankara's legacy. As of 2010, Compaoré was entering his 23rd year in power. He "has become immensely wealthy", while Burkina Faso ranks as the third least developed country in the world.[citation needed]

Between February and April 2011, the death of a schoolboy provoked an uprising throughout the country, coupled with a military mutiny and a magistrates' strike.

Government

With French help, Blaise Compaoré seized power in a coup d'état in 1987. He overthrew his long-time friend and ally Thomas Sankara, who was killed in the coup.[10]

The constitution of 2 June 1991 established a semi-presidential government: its parliament can be dissolved by the President of the Republic, who is elected for a term of seven years. In 2000, the constitution was amended to reduce the presidential term to five years and set term limits to two, preventing successive re-election . The amendment took effect during the 2005 elections. If passed beforehand, it would have prevented the incumbent president, Blaise Compaoré, from being reelected.

Other presidential candidates challenged the election results. But, in October 2005, the constitutional council ruled that, because Compaoré was the sitting president in 2000, the amendment would not apply to him until the end of his second term in office. This cleared the way for his candidacy in the 2005 election. On 13 November, Compaoré was reelected in a landslide, because of a divided political opposition.

In the 2010 November Presidential elections, President Compaoré was re-elected. Only 1.6 million Burkinabès voted, out of a total population 10 times that size.

The parliament consists of one chamber known as the National Assembly which has 111 seats with members elected to serve five-year terms. There is also a constitutional chamber, composed of ten members, and an economic and social council whose roles are purely consultative.

The Compaoré administration has worked to decentralize power by devolving some of its powers to regions and municipal authorities. But the widespread distrust of politicians and lack of political involvement by many residents complicates this process. Critics describe this as a hybrid decentralisation.[11]

Political freedoms are severely restricted in Burkina Faso Human rights organizations have criticised the Compaoré administration for numerous acts of state-sponsored violence against journalists and other politically active members of society.[citation needed]

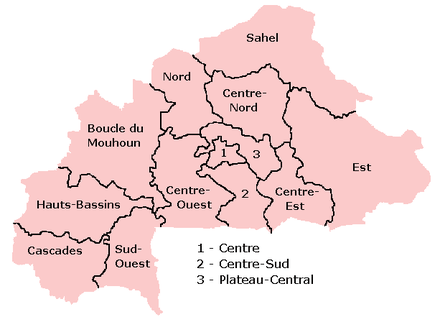

Regions, provinces, and departments

Burkina Faso is divided into thirteen regions, forty-five provinces, and 301 departments. The regions are:

- Boucle du Mouhoun

- Cascades

- Centre

- Centre-Est

- Centre-Nord

- Centre-Ouest

- Centre-Sud

- Est

- Hauts-Bassins

- Nord

- Plateau-Central

- Sahel

- Sud-Ouest

Military, police and security forces

The country employs numerous police and security forces, generally modeled after organizations used by French police, and France continues to provide significant support and training to police forces in Burkina Faso.[12] The Gendarmerie Nationale is organized along military lines, with most police services delivered at the brigade level.[13] The Gendarmerie operates under the authority of the Minister of Defence, and its members are employed chiefly in the rural areas and along borders.[13]

There is also a municipal police force controlled by the Ministry of Territorial Administration; a national police force controlled by the Ministry of Security; and an autonomous Presidential Security Regiment (Régiment de la Sécurité Présidentielle, or RSP), a ‘palace guard’ devoted to the protection of the President of the Republic.[13] Both the gendarmerie and the national police are subdivided into both administrative and judicial police functions; the former are detailed to protect public order and provide security, the latter are charged with criminal investigations.[13]

All foreigners and citizens are required to carry photo ID passports, or other forms of identification or risk a fine, and police spot identity checks are commonplace for persons traveling by auto, bush-taxi, or bus.[14][15]

The army consists of some 6,000 men in voluntary service, augmented by a part-time national People's Militia composed of civilians between 25 and 35 years of age who are trained in both military and civil duties. According to Jane’s Sentinel Country Risk Assessment, Burkina Faso's Army is undermanned for its force structure and poorly equipped, but has numbers of wheeled light-armour vehicles, and may have developed useful combat expertise through interventions in Liberia and elsewhere in Africa.

In terms of training and equipment, the regular Army is believed to be neglected in relation to the élite Presidential Security Regiment (RSP). Reports have emerged in recent years of disputes over pay and conditions.[16] There is an air force with some 19 operational aircraft, but no navy, as the country is landlocked. Military expenses constitute approximately 1.2% of the nation’s GDP.

In April 2011, there was an army mutiny; the president named new chiefs of staff, and a curfew was imposed in Ouagadougou.[17]

Geography and climate

Burkina Faso lies mostly between latitudes 9° and 15°N (a small area is north of 15°), and longitudes 6°W and 3°E.

It is made up of two major types of countryside. The larger part of the country is covered by a peneplain, which forms a gently undulating landscape with, in some areas, a few isolated hills, the last vestiges of a Precambrian massif. The southwest of the country, on the other hand, forms a sandstone massif, where the highest peak, Ténakourou, is found at an elevation of 749 meters (2,457 ft). The massif is bordered by sheer cliffs up to 150 meters (492 ft) high. The average altitude of Burkina Faso is 400 meters (1,312 ft) and the difference between the highest and lowest terrain is no greater than 600 meters (1,969 ft). Burkina Faso is therefore a relatively flat country.

The country owes its former name of Upper Volta to three rivers which cross it: the Black Volta (or Mouhoun), the White Volta (Nakambé) and the Red Volta (Nazinon). The Black Volta is one of the country's only two rivers which flow year-round, the other being the Komoé, which flows to the southwest. The basin of the Niger River also drains 27% of the country's surface.

The Niger's tributaries – the Béli, the Gorouol, the Goudébo and the Dargol – are seasonal streams and flow for only four to six months a year. They still can flood and overflow, however. The country also contains numerous lakes – the principal ones are Tingrela, Bam and Dem. The country contains large ponds, as well, such as Oursi, Béli, Yomboli and Markoye. Water shortages are often a problem, especially in the north of the country.

Burkina Faso has a primarily tropical climate with two very distinct seasons. In the rainy season, the country receives between 600 and 900 millimeters (23.6 and 35.4 in) of rainfall; in the dry season, the harmattan – a hot dry wind from the Sahara – blows. The rainy season lasts approximately four months, May/June to September, and is shorter in the north of the country. Three climatic zones can be defined: the Sahel, the Sudan-Sahel, and the Sudan-Guinea. The Sahel in the north typically receives less than 600 millimeters (23.6 in)[18] of rainfall per year and has high temperatures, 5–47 °C (41.0–116.6 °F).

A relatively dry tropical savanna, the Sahel extends beyond the borders of Burkina Faso, from the Horn of Africa to the Atlantic Ocean, and borders the Sahara to its north and the fertile region of the Sudan to the South. Situated between 11°3' and 13°5' north latitude, the Sudan-Sahel region is a transitional zone with regards to rainfall and temperature. Further to the south, the Sudan-Guinea zone receives more than 900 millimeters (35.4 in)[18] of rain each year and has cooler average temperatures.

Burkina Faso's natural resources include manganese, limestone, marble, phosphates, pumice, salt and small deposits of gold.

Burkina Faso's fauna and flora are protected in two national parks and several reserves: see List of national parks in Africa, Nature reserves of Burkina Faso.

Economy

Burkina Faso has one of the lowest GDP per capita figures in the world: $1,400.[19] Agriculture represents 32% of its gross domestic product and occupies 80% of the working population. It consists mostly of rearing livestock. Especially in the south and southwest, the people grow crops of sorghum, pearl millet, maize (corn), peanuts, rice and cotton, with surpluses to be sold. A large part of the economic activity of the country is funded by international aid.

Burkina Faso was ranked the 111th safest investment destination in the world in the March 2011 Euromoney Country Risk rankings.[20] Remittances used to be an important source of income to Burkina Faso until the 1990s, when unrest in Côte d'Ivoire, the main destination for Burkinabe emigrants, forced many to return home. Remittances now account for less than 1% of GDP.

Burkina Faso is part of the West African Monetary and Economic Union (UMEOA) and has adopted the CFA Franc. This is issued by the Central Bank of the West African States (BCEAO), situated in Dakar, Senegal. The BCEAO manages the monetary and reserve policy of the member states, and provides regulation and oversight of financial sector and banking activity. A legal framework regarding licensing, bank activities, organizational and capital requirements, inspections and sanctions (all applicable to all countries of the Union) is in place, having been reformed significantly in 1999. Micro-finance institutions are governed by a separate law, which regulates micro-finance activities in all WAEMU countries. The insurance sector is regulated through the Inter-African Conference on Insurance Markets (CIMA).[21]

There is mining of copper, iron, manganese, gold, cassiterite (tin ore), and phosphates.[22] These operations provide employment and generate international aid. In some cases, hospitals maintained by mining companies are available for use by local populations. Gold production increased 32% in 2011 at six gold mine sites, making Burkina Faso the fourth-largest gold producer in Africa, after South Africa, Mali and Ghana.[23]

Burkina Faso also hosts the International Art and Craft Fair, Ouagadougou. It is better known by its French name as SIAO, Le Salon International de l' Artisanat de Ouagadougou, and is one of the most important African handicraft fairs.

Burkina Faso is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[24]

While services remain underdeveloped, the National Office for Water and Sanitation (ONEA), a state-owned utility company run along commercial lines, is emerging as one of the best-performing utility companies in Africa, .[25] High levels of autonomy and a skilled and dedicated management has driven ONEA's ability to improve production of and access to clean water.[25] Since 2000, nearly 2 million more people have access to water in the four principal urban centres in the country; the company has kept the quality of infrastructure high (less than 18% of the water is lost through leaks – one of the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa), improved financial reporting, and increased its annual revenue by an average of 12% (well above inflation).[25] Challenges remain, including difficulties among some customers in paying for services, with the need to rely on international aid to expand its infrastructure.[25] The state-owned, commercially run venture has helped the nation reach its Millennium Development Goal (MDG) targets in water-related areas, and has grown as a viable company.[25]

Demographics

Burkina Faso's 15.3 million people belong to two major West African ethnic cultural groups—the Voltaic and the Mande (whose common language is Dioula). The Voltaic Mossi make up about one-half of the population. The Mossi claim descent from warriors who migrated to present-day Burkina Faso from the area of Ghana about 1100. They established an empire that lasted more than 800 years. Predominantly farmers, the Mossi kingdom is led by the Mogho Naba, whose court is in Ouagadougou.[26]

Burkina Faso is an ethnically integrated, secular state. Most of Burkina's people are concentrated in the south and center of the country, where their density sometimes exceeds 48 per square kilometer (125/sq. mi.). Hundreds of thousands of Burkinabe migrate regularly to Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, many for seasonal agricultural work. These flows of workers are affected by external events; the September 2002 coup attempt in Côte d'Ivoire and the ensuing fighting meant that hundreds of thousands of Burkinabe returned to Burkina Faso. The regional economy suffered when they were unable to work.[26]

The total fertility rate of Burkina Faso is 6.07 children born per woman (2012 estimates), the sixth highest in the world.[27]

The practice of slavery in Burkina Faso, as in the Sahel states in general, is an entrenched institution with a long history. It goes back to the Arab slave trade initiated by traders from the North, and it continues today.[28]

Health

Average life expectancy at birth in 2004 was estimated at 52 for females and 50 for males.[29] The median age of its inhabitants is 16.7. The estimated population growth rate is 3.109%.[30]

Central government spending on health was 3% in 2001.[31] As of 2009, studies estimated there were as few as 10 physicians per 100,000 people.[29] In addition, there were 41 nurses and 13 midwives per 100,000 people.[29] Demographic and Health Surveys has completed three surveys in Burkina Faso since 1993, and had another in 2009.[32]

In 2009, it was estimated that the adult HIV prevalence rate (ages 15–49) was 1.2%.[33] According to the 2011 UNAIDS Report, HIV prevalence is declining among pregnant women who attend antenatal clinics.[34]

According to a 2005 World Health Organization report, an estimated 72.5% of Burkina Faso's girls and women have suffered female genital mutilation, administered according to traditional rituals.[35]

Religion

Statistics on religion in Burkina Faso are inexact because Islam and Christianity are often practiced in tandem with indigenous religious beliefs. The Government of Burkina Faso 2006 census reported that 60.5% of the population practice Islam, and that the majority of this group belong to the Sunni branch,[36][37] while a small minority adheres to Shia branch. A significant number of Sunni Muslims identify with the Tijaniyah Sufi order. The Government also estimated that some 23.2% are Christians (19% being Roman Catholics and 4.2% members of various Protestant denominations); 15.3% follow traditional indigenous beliefs, 0.6% have other religions, and 0.4% have none (atheism is virtually nonexistent).[36][37]

A popular saying in Burkina Faso claims that "50% are Muslim, 50% are Christian, and 100% are animist". This shows the wide level of acceptance of the various religions amongst each other. Muslims and Christians also value ancient animist rites. The Great Mosque of Bobo-Dioulasso was built by people of different faiths working together.

Culture

Literature in Burkina Faso is based on the oral tradition, which remains important. In 1934, during French occupation, Dim-Dolobsom Ouedraogo published his Maximes, pensées et devinettes mossi (Maximes, Thoughts and Riddles of the Mossi), a record of the oral history of the Mossi people.[38] The oral tradition continued to have an influence on Burkinabè writers in the post-independence Burkina Faso of the 1960s, such as Nazi Boni and Roger Nikiema.[39] The 1960s saw a growth in the number of playwrights being published.[38] Since the 1970s, literature has developed in Burkina Faso with many more writers being published.[40]

The theatre of Burkina Faso combines traditional Burkinabè performance with the colonial influences and post-colonial efforts to educate rural people to produce a distinctive national theatre. Traditional ritual ceremonies of the many ethnic groups in Burkina Faso have long involved dancing with masks. Western-style theatre became common during colonial times, heavily influenced by French theatre. With independence came a new style of theatre inspired by forum theatre aimed at educating and entertaining Burkina Faso's rural people.

Arts and crafts

There is also a large artist community in Burkina Faso, especially in Ouagadougou. Much of the crafts produced are for the growing tourist industry. Tigoung Nonma was set up by a group of disabled artisans and sells crafts to provide a sustainable income for disabled artisans in Burkina Faso.[41]

Cuisine

Typical of West African cuisine, Burkina Faso's cuisine is based on staple foods of sorghum, millet, rice, maize, peanuts, potatoes, beans, yams and okra.[42] The most common sources of animal protein are chicken, chicken eggs and fresh water fish. A typical Burkinabè beverage is Banji or Palm Wine, which is fermented palm sap and Zoom-kom[?].

Cinema

The cinema of Burkina Faso is an important part of West African and African film industry.[43] Burkina's contribution to African cinema started with the establishment of the film festival FESPACO (Festival Panafricain du Cinéma et de la Télévision de Ouagadougou), which was launched as a film week in 1969. Many of the nation's filmmakers are known internationally and have won international prizes. For many years the headquarters of the Federation of Panafrican Filmmakers (FEPACI) was in Ouagadougou, rescued in 1983 from a period of moribund inactivity by the enthusiastic support and funding of President Sankara (In 2006 the Secretariat of FEPACI moved to South Africa but the headquarters of the organization is still in Ouagaoudougou). Among the best known directors from Burkina Faso are Gaston Kaboré, Idrissa Ouedraogo and Dani Kouyate.[44] Burkina also produces popular television series such as Bobodjiouf. The internationally known filmmakers such as Ouedraogo, Kabore, Yameogo, and Kouyate also make popular television series.

Sports

Sport in Burkina Faso is widespread and includes football (soccer), basketball, cycling, Rugby union, handball, tennis, athletics, boxing and martial arts. Football is very popular in Burkina Faso, played both professionally, and informally in towns and villages across the country. The national team is nicknamed "Les Etalons" ("the Stallions") in reference to the legendary horse of Princess Yennenga. In 1998, Burkina Faso hosted the African Cup of Nations for which the Omnisport Stadium in Bobo-Dioulasso was built. In 2013, Burkina Faso qualified for the African Cup of Nations in South Africa, reached the final, but then lost to Nigeria by the score of 0 to 1. The country is currently ranked 42nd in the FIFA World Rankings.[45]

Education

Education in Burkina Faso is divided into primary, secondary and higher education.[46] However schooling costs approximately CFA 50,000 ($97 USD) per year, which is far above the means of most Burkinabè families. Boys receive preference in schooling; as such, girls' education and literacy rates are far lower than their male counterparts. An increase in girls' schooling has been observed because of the government's policy of making school cheaper for girls and granting them more scholarships. In order to proceed from elementary to middle school, middle to high school or high school to college, national exams must be passed. Institutions of higher education include the University of Ouagadougou, The Polytechnical University in Bobo-Dioulasso and the University of Koudougou, which is also a teacher training institution. There are private colleges in the capital city of Ouagadougou but these are affordable by only a small portion of the population.

There is also the International School of Ouagadougou (ISO), an American-based private school located in Ouagadougou.

The UN Development Program Report ranks Burkina Faso as the country with the lowest level of literacy in the world, despite a concerted effort to double its literacy rate from 12.8% in 1990 to 25.3% in 2008.[47]

National and independent media

The nation's principal media outlet is its state-sponsored combined television and radio service, Radiodiffusion-Télévision Burkina (RTB).[48] RTB broadcasts on two medium-wave (AM) and several FM frequencies. Besides RTB, there are also a number of privately owned sports, cultural, music, and religious FM radio stations. RTB also maintains a worldwide short-wave news broadcast (Radio Nationale Burkina) in the French language from the capital at Ouagadougou using a 100 kW transmitter on 4.815 and 5.030 MHz.[49]

Attempts to develop an independent press and media in Burkina Faso have been intermittent. In 1998, investigative journalist Norbert Zongo, his brother Ernest, his driver, and another man were assassinated by unknown assailants, and the bodies burned. The crime was never solved.[50] However, an independent Commission of Inquiry later concluded that Norbert Zongo was killed for political reasons because of his investigative work into the death of David Ouedraogo, a chauffeur who worked for François Compaoré, President Blaise Compaoré's brother. In January 1999, François Compaoré was charged with the murder of David Ouedraogo, who had died as a result of torture in January 1998. The charges were later dropped by a military tribunal after an appeal. In August 2000, five members of the President's personal security guard detail (Régiment de la Sécurité Présidentielle, or RSP) were charged with the murder of Ouedraogo. RSP members Marcel Kafando, Edmond Koama, and Ousseini Yaro, investigated as suspects in the Norbert Zongo assassination, were convicted in the Ouedraogo case and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.[51][52]

Since the death of Norbert Zongo, several protests regarding the Zongo investigation and treatment of journalists have been prevented or dispersed by government police and security forces. In April 2007, popular radio reggae host Karim Sama, whose programs feature reggae songs interspersed with critical commentary on alleged government injustice and corruption, received several death threats.[53] Sama's personal car was later burned outside the private radio station Ouaga FM by unknown vandals.[54] In response, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) wrote to President Compaoré to request his government investigate the sending of e-mailed death threats to journalists and radio commentators in Burkina Faso who were critical of the government.[50] In December 2008, police in Ouagadougou questioned leaders of a protest march that called for a renewed investigation into the unsolved Zongo assassination. Among the marchers was Jean-Claude Meda, the president of the Association of Journalists of Burkina Faso.[55]

See also

- Ambassadors to Burkina Faso

- Foreign relations of Burkina Faso

- Holidays in Burkina Faso

- Index of Burkina Faso-related articles

- LGBT rights in Burkina Faso

- List of cities in Burkina Faso

- List of publications in Burkina Faso

- Music of Burkina Faso

- Outline of Burkina Faso

- Tourism in Burkina Faso

- Transport in Burkina Faso

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (French) INSD Burkina Faso

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Burkina Faso". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Distribution of family income – Gini index". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ↑ CFA Franc BCEAO. Codes: XOF / 952 ISO 4217 currency names and code elements. ISO. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ↑ Michel Izard, Moogo. L'émergence d'un espace étatique ouest-africain au XVIe siècle

- ↑ Mahir Saul and Patrick Royer, West African Challenge to Empire, 2001

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "More (Language of the Mossi Tribe) Phrase Book". World Digital Library. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ Kingfisher Geography Encyclopedia. ISBN 1-85613-582-9. Page 170

- ↑ Manning, Patrick (1988). Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa: 1880-198. Cambridge: New York.

- ↑ "Burkina Faso's Blaise Compaore sacks his government", BBC News, 15 April 2011

- ↑ Aristide Tiendrebeongo (March 2013). "Failure Likely". dandc.eu.

- ↑ Das, Dilip K. and Palmiotto, Michael J., World Police Encyclopedia, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-94250-0, ISBN 978-0-415-94250-8, (2005), pp. 139–141

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Das, pp. 139–141

- ↑ U.S. Dept. of State, Burkina Faso: Country Specific Information

- ↑ Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Sub-Saharan Africa: Burkina Faso

- ↑ Jane's Sentinel Security Assessment – West Africa, 15 April 2009

- ↑ "Burkina Faso capital under curfew after army mutiny". BBC News. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "SIM Country Profile: Burkina Faso". Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook, GDP Per Capita Rank Order".

- ↑ "Euromoney Country Risk". Euromoney Country Risk. Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ Burkina Faso Financial Sector Profile, MFW4A

- ↑ Profile – Burkina Faso

- ↑ "Search". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). 27 April 2012.

- ↑ "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". Retrieved 22 March 2009

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Peter Newborne 2011. Pipes and People: Progress in Water Supply in Burkina Faso's Cities, London: Overseas Development Institute

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Burkina Faso", U.S. Department of State, June 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ CIA – The World Factbook

- ↑ "West Africa slavery still widespread". BBC News. October 27, 2008.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 "WHO Country Offices in the WHO African Region – WHO | Regional Office for Africa". Afro.who.int. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ Burkina Faso. CIA World Factbook

- ↑ "Globalis – an interactive world map – Burkina Faso – Central government expenditures on health". Globalis.gvu.unu.edu. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Burkina Faso DHS Surveys,

- ↑ CIA world factbook: HIV/AIDS – adult prevalence rate

- ↑ UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report 2011, UNAIDS, retrieved 29 March 2012

- ↑ WHI.int

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Comité national du recensement (July 2008). "Recensement général de la population et de l'habitation de 2006". Conseil national de la statistique. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 International Religious Freedom Report 2010: Burkina Faso. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (17 November 2010). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Salhi, Kamal (1999). Francophone Voices. Intellect Books. p. 37. ISBN 1-902454-03-0.

- ↑ Allan, Tuzyline Jita (1997). Women's Studies Quarterly: Teaching African Literatures in a Global Literary. Feminist Press. p. 86. ISBN 1-55861-169-X.

- ↑ Marchais, Julien (2006). Burkina Faso (in French). Petit Futé. pp. 91–92. ISBN 2-7469-1601-0.

- ↑ Tigoung Nonma http://www.internationalservice.org.uk/where_we_work/burkina_faso/partners_burkina_faso.aspx

- ↑ "Oxfam's Cool Planet – Food in Burkina Faso". Oxfam. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Spaas, Lieve, "Burkina Faso," in The Francophone Film: A Struggle for Identity, pp. 232–246. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000

- ↑ Turégano, Teresa Hoefert, African Cinema and Europe: Close-Up on Burkina Faso, Florence: European Press Academic, 2005.

- ↑ "FIFA.com – The FIFA/Coca-Cola World Ranking". Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "Education – Burkina Faso". Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑

- ↑ "Radiodiffusion-Télévision Burkina". Rtb.bf. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Radio Station World, Burkina Faso: Governmental Broadcasting Agencies

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Committee to Protect Journalists, Burkina Faso

- ↑ Reporters Sans Frontieres, What’s Happening About The Inquiry Into Norbert Zongo’s Death?

- ↑ Reporters Sans Frontieres, Outrageous Denial Of Justice 21 July 2006

- ↑ IFEX, Radio Station Temporarily Pulls Programme After Host Receives Death Threats, 26 April 2007

- ↑ FreeMuse.org, Death threat against Reggae Radio Host, 3 May 2007

- ↑ Keita, Mohamed, Burkina Faso Police Question Zongo Protesters, Committee to Protect Journalists, 15 December 2008

Bibliography

- de Turégano, Teresa Hoefert, African Cinema and Europe: Close-up on Burkina Faso (European Press Academic Publishing, 2004).

- Engberg-Perderson, Lars, Endangering Development: Politics, Projects, and Environment in Burkina Faso (Praeger Publishers, 2003).

- Englebert, Pierre, Burkina Faso: Unsteady Statehood in West Africa (Perseus, 1999).

- Howorth, Chris, Rebuilding the Local Landscape: Environmental Management in Burkina Faso (Ashgate, 1999).

- McFarland, Daniel Miles and Rupley, Lawrence A, Historical Dictionary of Burkina Faso (Scarecrow Press, 1998).

- Manson, Katrina and Knight, James, Burkina Faso (Bradt Travel Guides, 2011).

- Roy, Christopher D and Wheelock, Thomas G B, Land of the Flying Masks: Art and Culture in Burkina Faso: The Thomas G.B. Wheelock Collection (Prestel Publishing, 2007).

- Sankara, Thomas, Thomas Sankara Speaks: The Burkina Faso Revolution 1983–1987 (Pathfinder Press, 2007).

- Sankara, Thomas, We are the Heirs of the World's Revolutions: Speeches from the Burkina Faso Revolution 1983–1987 (Pathfinder Press, 2007).

External links

| Find more about Burkina Faso at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Travel guide from Wikivoyage |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- (French) Premier Ministère, official government portal.

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- Burkina Faso entry at The World Factbook

- LeFaso.net, a news information site.

- Burkina Faso from UCB Libraries GovPubs.

- Burkina Faso on the Open Directory Project

- Burkina Faso profile from the BBC News.

Wikimedia Atlas of Burkina Faso

Wikimedia Atlas of Burkina Faso- News headline links from AllAfrica.com.

- Overseas Development Institute

- Country profile at New Internationalist.

- Key Development Forecasts for Burkina Faso from International Futures.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)