Brush-tailed mulgara

| Brush-tailed mulgara | |

|---|---|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Dasyuromorphia |

| Family: | Dasyuridae |

| Genus: | Dasycercus |

| Species: | D. blythi |

| Binomial name | |

| Dasycercus blythi Waite, 1904 | |

| |

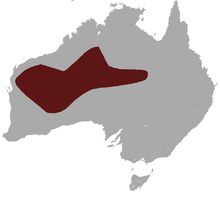

| Brush-tailed mulgara range | |

The brush-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus blythi or Dasycercus hillieri) is a large carnivorous Australian marsupial species. Its body mass is over 100grams, with males being slightly larger than females. Their body length is 15 cm, and tail length is 9 cm.

The taxonomy of the mulgaras has been confusing but as of 2005/06 two species are recognized: this species and the crest-tailed mulgara.

Physical appearance

Members of the Dasycercus genus have a body mass of over 100g, a length of 15 cm and tail length of 9 cm. Males are typically much larger than females.[2] The tail is “of moderate length, shorter than the head and body, incrassated (thickened); the proximal two-fifths covered with short still yellow hairs, the remainder with gradually lengthening black hairs that do not however form a crest. The whole of the lower surface is black, with the exception of a small proximal portion which is yellow.”[3] The upper portion of fur appears sandy and speckled with brown while the basal portion appears as a dark grey. The entirety of the underbelly, inner side of the limbs and lining of the pouch are pure white. Dentition shows two premolar teeth in both the upper and lower jaw, with the first observed as smaller than the second in the upper jaw. One feature that distinguishes D. blythi from other species of Dasycercus as observed in specimens is a gap between the second premolar and first molar.[3]

Habitat

D. blythi is widely distributed, having been observed during different expeditions in the north-western, central and south-western areas of the arid zone of Australia.[3] While once widespread and common throughout the central deserts of Australia, there has been an observed decline during the 1930s, resulting in a more fragmented distribution than previously observed.[2] Considering the sedentary behavior of D. blythi, their spinifex habitat is considered unusual, as it provides a less stable environment that is prone to things like fire.[4] From this, it is concluded that mulgaras exploit a larger variety of food sources to provide a stable caloric intake.[4] The size of the home range varies, growing largest during the mating period.[4] The recent reclassification of D. blythi as a unique species will require reevaluation of previous data collected about the population distributions of the Dasycercus family.[5]

Diet

D. blythi has a large variety in diet, consisting of different types of reptiles, invertebrates and even small mammals.[5]

Population dynamics

Populations often occur as scattered with relatively low population density while still being locally abundant.[5] Populations of D. blythi are unique in that they are sedentary populations rather than highly mobile, something often observed in smaller dasyurid species, whose group movements can range up to several kilometers.[6] Populations decline consistently during the winter and spring. This could be due to decreased food during the winter season, reducing available food for potentially pregnant females who would need to feed their young, along with reduction of available males due to aggressive competition for access to females earlier in the year.[6] Notably, dramatic increases in population are observed after large rainfall events, which are thought to come from D. blthi's competition with small rodent population explosions following such events.[7] Young female mothers have been observed to remain near the location of their birth, while young males often spread out, reducing competition for food, increasing opportunities to breed and avoid potential inbreeding. Once males find a home range, they become sedentary due to increased fitness by remaining in a familiar area rather than moving to new, uncharted territory.[6]

Reproduction

D. blythi breeds seasonally, producing only one litter a year with litters reproducing the year following their birth.[6] This reproductive strategy is different from that of other dasyurids, which often birth multiple litters a year to balance unpredictable reproductive conditions. It is thought that monoestry arises from increased access to larger and more reliably available prey, such as small mammals and birds, which are inaccessible by smaller dasyurids.[6] Unlike other dasyurids, males do not die after breeding.[8] Studies suggest that the onset of breeding occurs by the timing of the female oestrus, as males were observed to be in proper conditions to reproduce for about a month prior to the occurrence of breeding. Gestation ranges from 30 to 48 days, being extended by factors such as scarce food resources, low temperatures and frequency of torpor.[6] After birth, the young suckle between 12 and 15 weeks by hanging below the female's body due to a reduced pouch that is a pair of lateral flaps.[8] A maximum of six young have been found in the pouches of collected specimens.[9] The sex ratio in litters is 1:1 and while offspring may survive more than one mating season, only a small proportion of the population survive into a third year. In captivity, up to a 5 year lifespan has been observed.[5]

Behavior

D. blythi digs deep burrows, providing protection from the extremes of climate and potentially the predation by introduced European species to which other small and medium-sized desert mammals often fall prey.[6] Burrows have been observed to be about 0.5 meters deep and sometimes are shared by up to five. Certain populations see about half of the burrows used by an individual only once, while others were used over long periods of time, repeatedly.[2] While these burrows provide some protection from environmental temperature and the risk of dehydration, the sandy soil diffuses heat easily, limiting the burrow’s effectiveness for thermal buffering.[10]

Torpor is often employed by ‘’D. blythi’’, entering torpor at night until midday. This practice is not abandoned during reproduction even with the associated energy costs. Its benefit is felt both in summer and winter seasons, as torpor allows for reduction of endogenous heat production and maintenance of energy spent to be below basal metabolic rate.[10]

Conservation status

Numbers within the D. blythi population fluctuate greatly in accordance with climate conditions, which make population estimates difficult to establish, thus creating difficulty in tracking population trends. Historical confusion with classifications between D. cristicauda and D. blythi add another layer of complexity. The cause of decline in the D. blythi population is unknown and threatening processes have not been able to be confirmed; potential threats include changes in fire regimes, grazing by introduced herbivores such as cattle and rabbits and predation by introduced predators from European settlement. Another hypothesis is that environmental damage has had a negative impact on the mulgara population.[2] In order to provide further protection and future proliferation, animals surveys using targeted trapping and patch burning programs are used to create an ideal habitat.[11] Fire does not have a negative impact on population as long as 15% cover is maintained.[5]

Care for the mulgara habitat, especially with controlled burns, should employ a fire regime that burns a mosaic of land with no particular piece of land being burnt more often than three to five years.[12] This will provide a fire regime that leaves the necessary 15% cover intact for successful species proliferation.

References

- ↑ Woolley, P. (2008). Dasycercus blythi. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Pavey, C., J. Cole, and J. Woinarski. "Brush-tailed Mulgara (Mulgara) Dasycercus Blythi." Threatened Species of the Northern Territory. Northern Territory Government Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts, Dec. 2006. Web.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Woolley, P. "The Species of Dasycercus Peters, 1875 (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae)." Memoirs of Museum Victoria 62.2 (2005): 213-21. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Körtner, G., C. Pavey, and F. Geiser. "Spatial Ecology of the Mulgara in Arid Australia: Impact of Fire History on Home Range Size and Burrow Use." Journal of Zoology 273 (2007): 350-57. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Dasycercus Blythi." (Brush-tailed Mulgara). IUCN, 2013. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Masters, P. "Population Dynamics of Dasycercus Blythi (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae) in Central Australia." Wildlife Research 39.6 (2012): 419-28. Print.

- ↑ Letnic, M., and C. R. Dickman. "Resource Pulses and Mammalian Dynamics: Conceptual Models for Hummock Grasslands and Other Australian Desert Habitats." Biological Reviews 85 (2010): 501-21. Print.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Mulgara." Australian Wildlife Conservancy, n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

- ↑ Woolley, P. "Studies on the Crest-tailed Mulgara Dasycercus Cristicauda and the Brush-tailed Mulgara Dasycercus Blythi (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae)." The University of Sydney Library, Australia 28.1 (2006): 117-20. Print.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Körtner, G., C. Pavey, and F. Geiser. "Thermal Biology, Torpor, and Activity in Free-living Mulgaras in Arid Zone Australia during the Winter Reproductive Season." Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 81.4 (2008): 442-51. Print.

- ↑ "Mammals." Parks Australia, 17 Dec. 2012. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.

- ↑ "Management Guidelines for Brush-tailed Mulgara Dasycercus Blythi | Northern Land Manager." Management Guidelines for Brush-tailed Mulgara Dasycercus Blythi | Northern Land Manager. North Land Manager, n.d. Web. 02 Dec. 2013.