Brough Castle

| Brough Castle | |

|---|---|

| Brough, Cumbria, England | |

| |

| The ruined keep at Brough Castle | |

| Coordinates | grid reference NY791141 |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public |

Yes |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone |

| Events | Great Revolt of 1173-74 |

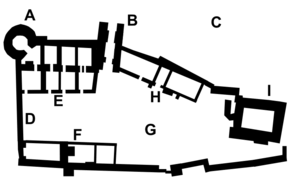

Brough Castle is a ruined castle in the village of Brough, England. The castle was built by William Rufus around 1092 within the old Roman fort of Verterae to protect a key route through the Pennine mountains. The initial motte and bailey castle was attacked and destroyed by the Scots in 1174 during the Great Revolt against Henry II. Rebuilt after the war, a square keep was constructed and the rest of the castle converted to stone.

The Clifford family took possession of Brough after the Second Barons' War in the 1260s; they built Clifford's Tower and undertook a sequence of renovations to the castle, creating a fortification in a typical northern English style. In 1521, however, Henry Clifford held a Christmas feast at the castle, after which a major fire broke out, destroying the property. The castle remained abandoned until Lady Anne Clifford restored the property between 1659 and 1661, using it as one of her northern country homes. In 1666 another fire broke out, once again rendering the castle uninhabitable. Brough Castle went into sharp decline and was stripped first of its fittings and then its stonework. The castle's masonry began to collapse around 1800.

In 1921, Brough Castle was given to the state and is now run by English Heritage as a tourist attraction. It is a listed building and a scheduled monument.

11th century

Brough Castle was built on the site of the Roman fort of Verterae, a three-acre fortification that was occupied until the 5th century.[1] The site protected the Stainmore Pass that stretched from the River Eden across the Pennines, and the Roman road connecting Carlisle and Ermine Street, a valuable trading route during the period.[2]

Following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, William the Conqueror subdued the north of the country in a sequence of harsh campaigns, and the north-west region became a contested border territory between the Normans and the Scottish kings.[3] William's son, William Rufus, invaded the north-west in 1091 and built Brough Castle around 1092, placing it in the north part of the old Roman fort in order to make use of the existing earthworks, in a similar way to nearby Brougham and Lancaster.[4] The north side of the site overlooks the River Eden.[5] This castle appears to have been a motte and bailey design; the keep had stone foundations and a main structure built from timber, while the rest of the former fort was turned into a palisaded bailey.[6][nb 1] The village of Church Brough was created alongside the castle at around the same time, in the form of a planned settlement, part of the Norman colonisation of the low-lands in the region.[7]

12th century

The region around Brough continued to be disputed between the kings of England and Scotland; in 1173, William the Lion of Scotland invaded as part of the Great Revolt against the rule of Henry II. William's army struck south but failed to take Wark and moved on to attack Carlisle instead; when that failed too, they successfully took Appleby before turning their attention to Brough.[8]

Brough, guarded by six knights, put up a strong resistance, but William took the outer defences and then besieged the keep, threatening to execute the garrison if the castle was not surrendered.[9] The keep was set on fire, forcing the surrender of the garrison, including one knight who, according the chronicler Jordan Fantosme, fought on first with spears and then wooden stakes, until finally overwhelmed.[10] William then destroyed the remaining defences of the castle using Flemish mercenary troops.[11] Henry II's forces defeated William at the battle of Alnwick and Brough Castle was recovered later in the year.[12]

Henry II had a square stone keep constructed in the 1180s by first Theobald de Valoignes and then Hugh de Morville, who rebuilt the remains of the castle.[13] It was placed into the bailey wall, allowing it to directly support the outer defences.[14] Thomas de Wyrkington conducted further work between 1199 and 1202 for King John, converting the castle entirely into stone.[12]

13th–15th centuries

King John granted the lordship of Westmoreland, including Brough, to Robert de Vieuxpont in 1203.[12] Robert enlarged the castle in order to exert his authority over the region, where he was competing for control with other members of his extended family.[15] Robert died in 1228, leaving substantial debts of £2,000 to the Crown and passing the castle to his young son, John.[16][nb 2] His son's guardian, Hubert de Burgh appointed the Prior of Carlisle to run the estate and the castle was left to fall into ruin.[16] John died supporting the rebels during the Second Barons' War between 1264 and 1267 and his lands were divided between his two daughters, Isabel and Idonea.[17] Isabel de Vieuxpont inherited Brough and the eastern Vieuxpont estates; Henry III gave guardianship of some of these lands to Roger de Clifford; Roger then married Isabel, acquiring all her lands and beginning a long period of Clifford control of the castle.[18]

The Cliffords successfully recombined the former Vieuxpont estates by 1333, and were able to controlled the Eden valley through their castles at Appleby, Brougham, Pendragon and Brough.[19] Robert Clifford controlled Brough by around 1308 and improved the defences, rebuilding the east wall and constructing a new hall, alongside his apartments which were located in a new circular tower, called Clifford's Tower.[20] These apartments may have been similar to those surviving at Appleby Castle, also built by Robert.[21]

Robert died fighting the Scots at the battle of Bannockburn and the region around the castle was attacked in 1314 and 1319, causing significant damage to neighbouring Church Brough.[22] Around this time the village of Market Brough was established along the road overlooked by the castle, in an attempt by the Cliffords to maximise the possibilities for profits from trade along the valley.[23] Market Brough acquired a royal charter in 1330 and seems to have rapidly overtaken Church Brough as the main settlement in the area.[22]

In the 1380s Roger, the fifth baron, decided to modify the castle, partially to improve the defences.[12] Roger conducted work to most of the Clifford castles in the area and at Brough he rebuilt the south wall and reconstructed the living accommodation, replacing the existing hall with a more fashionable first-floor hall and chamber block.[24] Clifford's Tower was converted for use as bedrooms and some of the old hall was converted into a solar.[20] in With the exception of Clifford's Tower, these renovations at Brough reflected the popular architectural style of castles in the north of England at the time, stressing square lines and towers in preference to the rounder shapes prevalent in the south.[25] The bailey was cobbled over at around this time.[26]

The gatehouse was reinforced with buttresses and an additional courtyard built within the bailey around 1450, possibly by Thomas Clifford.[20] During the Wars of the Roses between the rival houses of the Lancastrians and the Yorkists, the Clifford supported the Lancastrians. Thomas died in 1455, followed by his son John in 1461; Brough was temporarily seized from the Cliffords by the Yorkists, until John's son Henry was restored to his lands in 1485 by Henry VII.[20]

16th–17th centuries

Henry Clifford used the castle until 1521, when a fire broke out after a lavish Christmas Feast, destroying the inhabitable parts of the castle.[27] Henry died shortly afterwards and the castle remained ruined for many years.[5]

The castle was restored in the 17th century by Lady Anne Clifford, a major landowner in the Clifford family who retired to the north during the years of the Commonwealth after the English Civil War.[28] Although Anne was a royalist, she was protected by powerful friends within the ruling Parliamentary faction and able to enjoy her properties freely.[29] She rebuilt a number of the Clifford castles, including Brough, where she conducted restoration work between 1659 and 1661.[30] Anne undertook more work at Brough than any where else on her estates, aiming to restore it to its pre-1521 condition.[31] Although Anne would have been familiar with contemporary styles, her restoration work was quite traditional in approach, drawing on existing northern castle architecture and deliberately trying to recreate 12th century features in the keep.[32] As part of this work, new windows, a ground floor entrance to the keep and new service accommodation was installed to allow her to live a late 17th century lifestyle, and the castle had 24 fireplaces by 1665.[33]

Anne renamed Brough's keep as "the Roman Tower", in the belief that it had been built by the Romans.[34] She divided her time at the castle between living in Clifford's Tower, part of the castle's apartments and, as work progressed, the keep; by 1665, she was able to spend her Christmas at the castle for the first time.[35] In 1666 another fire struck the castle, however, rendering it uninhabitable.[12] In the aftermath, the remaining buildings in the bailey was converted for use as a law court, and Anne died in 1676, the castle unrestored.[36]

18th–21st centuries

Anne's daughter, Margaret, married John Tufton, the Earl of Thanet.[5] John's son, Thomas, stripped the castle around 1695 to support the reconstruction of Appleby Castle.[5] The furnishings were sold in 1714 and in 1763 much of the stone from Clifford's Tower was plundered for use in the construction of Brough Mill; the castle was subsequently completely abandoned.[12] The south-west corner of the keep partially collapsed around 1800.[29]

In 1920 more of the south-west corner collapsed and the castle's owner, Lord Hothfield, gave the property to the Office of Works.[29] Work to stabilise the ruins was carried out and the castle, as a listed building and ancient monument, eventually passed into the control of English Heritage as a tourist attraction.[29] There were initial archaeological excavations on the site in 1925, and then further work in 1970-71, 1993, 2007 and 2009.[37] Erosion continues to be a threat to the castle's masonry, and as of 2010 English Heritage considered the castle's condition to be declining, with some parts at particular risk.[38]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Opinions vary as to how much of the keep was wooden; John Charlton concludes that the greater part of the keep was stone, while Higham and Barker have more recently concluded that the fortification was primarily wooden.[1]

- ↑ It is impossible to accurately compare 13th century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £600 represents around three times the typical average annual income for a typical baron in 1200.[2]

References

- ↑ Gaskell, Noakes and Wood, p.4.

- ↑ Noakes, p.4; Pettifer, p.266.

- ↑ Noakes, p.4; Charlton, p.14.

- ↑ Gaskell, Noakes and Wood, p.4; Pounds, p.43.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Mackenzie, p.283.

- ↑ Noakes, p.4; Higham and Barker, p.122; Charlton, p.14.

- ↑ Gaskell, Noakes and Wood, p.5; Pounds, p.44.

- ↑ Brown, pp.166–167.

- ↑ Goodall, p.138; Brown, pp.167, 169–170; Charlton, p.14.

- ↑ Goodall, p.138; Brown, pp.168–169; Charlton, p.14.

- ↑ Goodall, p.138; Charlton, p.15.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Noakes, p.5.

- ↑ Pettifer, p.266; Gaskill, Noakes and Woods, p.5; Noakes, p.5.

- ↑ Hulme, p.216; Noakes, p.5.

- ↑ Goodall, p.164.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Noakes, p.5; Charlton, p.16.

- ↑ Charlton, p.16.

- ↑ Pounds, p.142.

- ↑ Emery, p.169; Charlton, p.16.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Charlton, p.17.

- ↑ Goodall, p.244.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gaskell, Noakes and Woods, p.5.

- ↑ Creighton, p.166.

- ↑ Emery, pp.170, 262; Pounds, p.188; Charlton, p.17.

- ↑ King, p.153.

- ↑ Pettifer, p.266.

- ↑ Goodall, p.408; Charlton, p.17.

- ↑ Johnson, p.117.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Charlton, p.20.

- ↑ Goodall, p.244; Johnson, p.117.

- ↑ Chew, p.107.

- ↑ Johnson, p.117; Chew, p.109.

- ↑ Chew, pp.107-108.

- ↑ Goodall, p.481.

- ↑ Goodall, p.244; Chew, p.109..

- ↑ Noakes, p.5; Charlton, p.20.

- ↑ Gaskill, Noakes and Woods, pp.5-6.

- ↑ Heritage at Risk Register 2010 North West , p.32, English Heritage, accessed 31 March 2012.

Bibliography

- Brown, R. Allen (1962). English Castles. London: Batsford. OCLC 1392314.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton (2005). Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 9781904768678.

- Charlton, John (1986). Brough Castle, Cumbria. London: English Heritage. ISBN 1850742650.

- Chew, Elizabeth V. (2003). "'Repaired by me to my Exceedingly Great Cost and Charges': Anne Clifford and the Uses of Architecture". In Hills, Helen. Architecture and the Politics of Gender in Early Modern Europe. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Press. ISBN 9780754603092.

- Emery, Anthony (1996). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Northern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521497237.

- Gaskill, Nicola; Noakes, Helen; Woods, Frances (2009). An Archaeological Watching Brief and Investigation at Brough Castle, Church Brough, Cumbria. Alston, UK: North Pennines Archaeology.

- Goodall, John (1962). The English Castle. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300110586.

- Hulme, Richard (2008). "Twelfth Century Great Towers – The Case for the Defence". The Castle Studies Group Journal (21): 209–229.

- Johnson, Matthew (2002). Behind the Castle Gate: From Medieval to Renaissance. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415258876.

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415003504.

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896). The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 504892038.

- Noakes, Helen (2008). An Archaeological Field Evaluation at Brough Castle, Church Brough, Cumbria. Alston, UK: North Pennines Archaeology.

- Pettifer, Adrian (2002). English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851157825.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521458283.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brough Castle. |

| ||||||||||||||